Chapter 14

Financial Analysis and Control in the Dental Office

Put all your eggs in one basket and WATCH THAT BASKET!

Mark Twain

Office production

Office collections

Practice costs

Patient generation

Case acceptance

Staff effectiveness

Overhead ratio

Office monthly production

Service mix

AR amount

Collection ratio

AR over 60 days

Managed care percentage

Managed care efficiency

Total staff percentage

Variable cost ratio

New patients per month

Recall effectiveness

Marketing dollars per new patient

Case acceptance ratio

basic profitability formula

collection ratio

fee profile

managed care efficiency

managed care percentage

mix of devices

lab-to-labor ratio

overhead

overhead percentage

ratios

staff efficiency ratios

standards

variable cost ratio

Financial control looks at the “numbers” of the practice in an attempt to maximize profit from the practice. Dentists can make the financial control process as simple or as complex as they want. The possibilities for gathering data are endless. If dentists have an in-office computer system, the problem is often deciding which of the many reports and analyses they truly need. Dentists should not inundate themselves with information and should look for major problem areas first. They should start with some basic ratios (production, profitability, and collection ratios) and look for problems in these areas. If dentists find no major problems, they probably do not need to do any in-depth analysis. Conversely, a practice may be having problems in one certain area that needs particular, additional attention. Other areas may be functioning well and only require periodic monitoring.

Most people only think of costs when they look at financial control. The revenue side is equally important. For example, costs may be under control, but low production leads to low profitability. Many also think that business owners should reduce overhead wherever possible; however, there is “good” overhead and “bad” overhead. Good overhead is money that dentists spend that makes them more money. Bad overhead does not contribute to making more money; it is, therefore, wasted. For example, suppose a dentist hires a new staff member with pay of $15 an hour. That staff member allows the dentist to produce an additional $50 per hour. That is money well spent (a good piece of overhead). However, if the office does not increase production enough to make up for the additional costs, the additional money spent on the staff member would be bad overhead. This is simple in idea. The problem is trying to decide which costs cause waste and which contribute to the practice’s profitability. That is what financial analysis is about.

Many dentists want to leave the numbers to an accountant. Such a policy is OK if the accountant is familiar with dental practices and understands a dentist’s personal philosophy, goals, and where the dentist wants the office to be. The problem is that most accountants do not know these things. They are more interested in tax numbers. If a dentist finds an accountant who is knowledgeable about dental practice numbers, he or she should use that accountant to his or her advantage. If not, then a dentist will need to be his or her own financial analyst.

Steps in the Financial Control Process

Understanding the financial control process is important. Otherwise, a dentist might apply a simple rule that is not appropriate for the given situation. The previous chapter on office finance presents the fundamental information on finances in the office. This chapter continues the analysis by looking at how those concepts should be interpreted.

Step 1: Setting Standards

The first step is for a dentist to establish a target against which he or she will measure subsequent practice activity. The standard serves as the mechanism to monitor practice performance and should meet the needs of a particular practice. For example, a dentist may set a standard of wanting to see 200 recall patients per month. A slight deviation from this standard (180–220 patients per month) is expected, but a major shortage of recall patients (50 patients per month) would suggest a more serious problem.

Dentists often use national or regional averages as the basis of setting a standard. For example, an average overhead ratio may be 65 percent. Does that mean that a dentist’s practice should have a 65 percent overhead ratio? Not necessarily. If a dentist hits this mark, then half of the practices will have a higher mark and half will have a lower percentage. A dentist’s practice may be a start-up practice in which he or she is not fully scheduled. So any time a dentist compares his or her practice to others as a standard, that dentist must be sure that the analysis is adjusted appropriately.

The key is to decide the appropriate standard—what is it that a dentist wants to measure? He or she should look for measures that relate to the changes made or suspected problems rather than trying to measure everything. In this way a dentist can make a higher impact by concentrating on specific target areas rather than trying a “shotgun” approach to measuring his or her practice.

Step 2: Measuring Performance

Although standards set forth “what should be,” measuring performance examines what has happened in a practice. This reality measure is crucial to successful and effective practice management control. Dentists may make these measurements daily, monthly, or annually depending on the variable. Practice policy may define them such as “all patients receive a survey questionnaire when they complete treatment and are placed on recall status,” or dentists may gather them from ongoing practice record systems (day sheets, time records, etc.). The measures may be formal or informal, simple or elaborate. Whatever system is used, it should relate directly to the standard a dentist wishes to measure. It should also represent the entire dental practice and be reliable (consistent) and valid (measure what is intended). Reliable measures require, for example, that a dentist uses the same survey questionnaire for the exit interview of patients who have completed treatment. Dentists cannot expect to gain useful information if they ask different questions each time the questionnaire is given. Valid standards measure what they are supposed to measure. “Percent of recall patients seen by the hygienist,” for example, may be a measure of scheduling rather than hygienist performance.

Historical practice data will serve as a good starting point for determining future standards. Previous costs, revenues, or intangible measures should all be considered. A dentist may also find comparative standards from other dental practices useful. One excellent source of this data is from the American Dental Association’s (ADA) periodic “Survey of Dental Practice.” Other sources include the popular dental press (e.g., Dental Economics), an accountant, and national organizations, such as the ADA.

Step 3: Comparing Performance to Standards

In this step, dentists compare actual performance with what should have happened. This comparison is easy if there are established standards and measured information. The actual results and the desired outcomes will rarely match exactly. A dentist should set acceptable ranges for performance, evaluate the performance outcomes within these ranges, and then look for exceptions. Management by exception permits a dentist to concentrate on the significant problems that may arise in the practice without becoming overburdened with the minutia of all the standards. For example, as stated previously, if a dentist has a standard of wanting to see 200 recall patients per month but only sees 180 in a month and 197 the next month, he or she may not be too concerned about the 2-month average of 188 recalls a month. However, if he or she saw only 55 recalls 1 month and 127 the next month, the dentist would want to explore more fully the reasons for much lower-than-expected recall patient visits.

Dentists should be sure to pick an appropriate period for their analysis. Many numbers and ratios may fluctuate widely over a given time range. If so, a dentist would want to lengthen the period being reviewed. Dentists should track some numbers daily. Some offices set daily production goals. Other offices feel that daily production is too unsteady and prefer, instead to use monthly numbers. If a dentist examines a month in which he or she took 2 weeks of vacation, unrepresentative numbers will be the result. A quarterly analysis might be more appropriate. Most aggressive dentists look at their numbers monthly. Many others look quarterly, believing that this smoothes out the monthly variations. Still other dentists only look at numbers when accountants prepare their taxes. The final group never looks at them. They simply believe that things are going OK, and they are making an adequate living, so why bother? All are perfectly acceptable.

Step 4: Correcting Deviations

This is the essence of control. It is during this step that dentists take actions to adjust the plan or operation of the dental practice. For example, if the office did not meet the standard of “95 percent of recall patients due are appointed each month,” the dentist would take corrective actions to meet the standard in the future.

Correcting deviations from planned standards requires astute problem-solving skills. Knowledge of dental practice management helps a dentist decide when to modify standards, replace personnel, restructure office policies, set up new staff development programs, and so forth. The key to setting up an effective control system is taking corrective action. Failure to act when a dentist detects a substantial deviation in a planned standard undermines the purpose of this evaluation system.

The plans that a dentist started may be inappropriate for the actual conditions that develop. Then, he or she needs to correct the plan itself. If a dentist assumes a steady economic climate and plans to expand the dental practice by finding additional office space, equipment, or staff and the general economy declines instead, he or she will need to alter the plan. If a dentist only finds slight deviations, he or she may decide simply to monitor these changes and take action when they reach a certain point. For example, if a patient satisfaction survey reveals slight displeasure with the receptionist from one or two patients, a dentist would probably choose to monitor this situation rather than discuss it with the receptionist. If other patients also reported dissatisfaction over a period, then the dentist may decide to speak to the receptionist.

Profitability Analysis

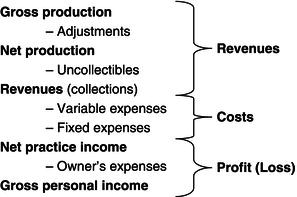

The basic statement that shows profitability is profit-and-loss (P&L) statement (Fig. 14.1). What dentists want to do is to maximize the “bottom line” and make practices as profitable as possible, given certain constraints. (Dentists could increase income by working 80 hours per week, but most are not willing to do that.) There is no magic formula. To increase profit, dentists can only increase revenues, decrease costs, or make some combination of the two. So dentists need to examine the components of the income formula (both revenues and costs) when planning an office analysis.

Figure 14.1 Profit-and-loss statement

Dental Practice Revenues

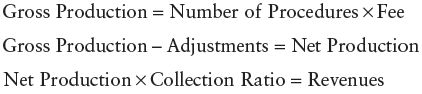

Total collections (gross practice revenues) are the result of the number and type of procedures that dentists do, the fee that they charge for each of those procedures, any adjustments granted from full fee, and the collection ratio shown by the office. If collections are low, any of the four factors may be at fault. The following formulas describe these relationships:

Gross production is the total amount of dentistry produced by the office for the period, before any discounts or adjustments. Production levels vary with the number and types of procedures done and the fee charged for those procedures. It is the combination of all individual procedures and fees. Production is obviously the cornerstone of practice profitability in a dental practice because without production, no money flows through the office.

Adjustments are the amounts of money that the office “wrote off” for discounts because of payment plan (such as Medicaid) requirements, marketing efforts, or professional courtesies. Dentists may decide to track particular types of adjustments to detect the impact of that plan has on the office finances. For example, a dentist may wish to track how much Medicaid and capitation plan payment that the office adjusts each month.

Net production is mathematically, production less adjustments. It is the amount of money that dentists want to collect. Because dentists do not expect to collect the money that has been adjusted, they should exclude those amounts from many analyses.

The collection ratio is the percentage of net production that the office collects from patients and insurance companies. Uncollectibles are the monies that dentists have given up trying to collect. Mathematically, it (collection ratio) is multiplied by net production.

Revenues (collections) are the amounts of money (i.e., cash, checks, and credit cards) that crossed the receptionist’s desk for the period. Some of this may be from production for this month, whereas the rest of it may be for dentistry done several months ago but is now being paid. Individuals, insurance companies, or government programs may make payments.

Dental Practice Costs

Cost for a dental practice fall into two conceptual categories, fixed and variable.

Fixed costs do not change with production. Rent, for example, remains the same regardless if 10 or 100 patients are seen in a month.

Variable costs change directly with the level of gross production. These are supplies and laboratory charges. If a dentist produces twice as much dentistry in a month, he or she would logically expect to have twice the lab and supply bill from the increased amount of work.

Profit

Profit is the money that is available for the owner of the practice to take from the practice accounts and use for personal benefit and enjoyment.

Net practice income is the amount that is available to the owner as profit from operating the practice.

Owner’s expenses are expenses that the owner has chosen to take from the practice that they could have taken as profit. Examples include personal automobile expenses, personal retirement plan contributions, and many continuing education expenses. Because taking these costs is discretionary, they are included in the practice profit.

Gross personal income is the amount that the practice owner claims for initial personal tax computations.

Critical Success Factors

There are six factors that lead to business success of the dental practice. Dentists should aim their practice assessment at these factors, judging whether they are meeting the factors. Box 14.1 lists the success factors. The rest of Section 2 gives much more detail on each of these items, showing how dentists can change the practice to improve these indicators.

Factor 1: Maintaining Production

Production is the key to practice health (Box 14.2). Unless dentists are generating an adequate production (and therefore dollars), no amount of management skill can gain profitability. Production is a result of both the number of procedures done and the fee charges for each pro/>

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses