Treatment of Temporomandibular Joint Disorders

“INTRACAPSULAR JOINT DISORDER; THE MECHANICAL PART OF TMD.”

—JPO

THIS CHAPTER DISCUSSES the management of capsular and intracapsular temporomandibular joint (TMJ) disorders. Each subdivision of this category is discussed from the early mild symptoms of disc displacements to the more severe and more difficult to manage inflammatory disorders. The correct management of disc derangement disorders is predicated on two factors: making a correct diagnosis and understanding the natural course of the disorder. Emphasis has already been placed on establishing a correct diagnosis. Each of the categories of TMJ disorders represents a clinical condition that is treated in a particular manner. An incorrect diagnosis leads to mismanagement and ultimate treatment failure.

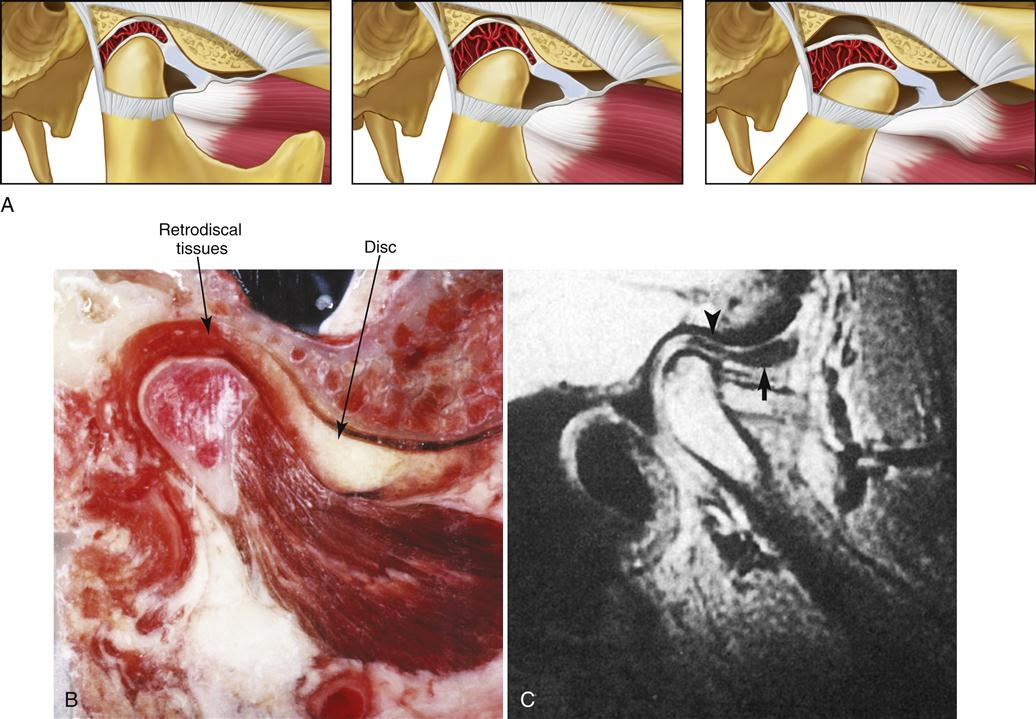

Successful management of intracapsular joint disorders is also based on the clinician’s understanding of the natural course of the disorder. In Chapter 8 a progressive description of disc derangement disorders was presented. As the morphology of the disc becomes more altered and ligaments more elongated, the disc becomes progressively displaced and eventually dislocated. Once the disc is dislocated, the condyle begins to function on the retrodiscal tissues. These tissues begin to break down, leading to osteoarthritis or degenerative joint disease. Although this sequence is often clinically evident, it does not account for the outcome of all intracapsular disorders.

Epidemiologic studies reveal that asymptomatic joint sounds are very common. Many studies1–11 reveal that TMJ sounds are detected in 25% to 35% of the general population. This poses an interesting question: If all joint sounds are not progressive, which sounds should be treated? In my opinion only joint sounds associated with pain should be considered for treatment. The pain in this instance must be intracapsular in origin. In other words, patients who report with extracapsular muscle pain and a painless clicking point should not be managed for the disc derangement disorder. This approach will lead to treatment failure since it does not address the source of the pain. This concept will be further discussed, with literature support, later in this chapter.

TMJ disorders are a broad category of temporomandibular disorders (TMDs) that arise from capsular and intracapsular structures. This category is divided into three subcategories: derangements of the condyle-disc complex, structural incompatibility of the articular surfaces, and inflammatory disorders.

Derangements of the Condyle-Disc Complex

This category can be divided into two subcategories for the purpose of treatment: disc displacements/disc dislocations with reduction and disc dislocations without reduction.

Disc Displacements and Disc Dislocations with Reduction

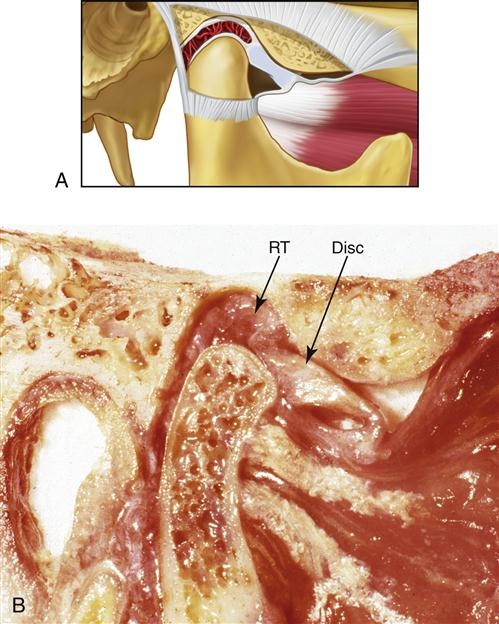

Disc displacements and disc dislocations with reduction represent the early stages of disc derangement disorders (Figures 13-1 and 13-2). The clinical signs and symptoms relate to alterations or derangements in the condyle-disc complex.

Etiology

Disc derangement disorders result from elongation of the capsular and discal ligaments coupled with thinning of the articular disc. These changes commonly result from either macro- or microtrauma. Macrotrauma is often reported in the history, whereas microtrauma may go unnoticed by the patient. Common sources of microtrauma are hypoxia-reperfusion injuries,12–16 bruxism,17 and orthopedic instability (Figure 13-3). Some studies18–21 suggest that the class II division 2 malocclusion is commonly associated with orthopedic instability and therefore an etiologic factor related to disc derangement disorders (Figure 13-4). Since not all studies22–33 support this relationship (see Chapter 7) other factors must be considered. As previously discussed, orthopedic instability plus joint loading seem to combine as etiologic factors in some disc derangement disorders.

Another concept that must be appreciated is that perhaps the disorder actually begins at the cellular level and then progresses to the gross changes seen clinically. In other words, unusually heavy and prolonged loading of the articular tissues exceeds the functional capacity of the articular tissues and breakdown begins (hypoxia-reperfusion injury). When the functional limitation has been exceeded, the collagen fibrils become fragmented, resulting in a decrease in the stiffness of the collagen network. This allows the proteoglycan-water gel to swell and flow out into the joint space, leading to a softening of the articular surface. This softening is called chondromalacia.34 The early stages of chondromalacia are reversible if the excessive loading is reduced. If, however, the loading continues to exceed the capacity of the articular tissues, irreversible changes can occur. Regions of fibrillation can begin to develop, resulting in focal roughening of the articular surfaces.35 This alters the frictional characteristics of the surface and may lead to sticking of the articular surfaces (adherences), causing changes in the mechanics of condyle-disc movement. Continued sticking (adhesions) and/or roughening leads to strains on the discal ligaments during movement and eventually disc displacements.36 In this situation microtrauma is the responsible etiology for the disc displacement.

History

When macrotrauma is the etiology, the patient will often relate an event that precipitated the disorder, such as a motor vehicle accident or blow to the face.37–46 A good history will frequently reveal the more subtle findings of bruxism. The patient will also report the presence of joint sounds and may even report a catching sensation during mouth opening. The presence of pain associated with this dysfunction is important.

Clinical characteristics

The clinical examination reveals a relatively normal range of motion with restriction occurring only in association with the pain. Discal movement can be felt by palpating the joints during opening and closing. Deviations in the opening pathway are common.

Definitive treatment

Definitive treatment for a disc displacement is to reestablish a normal condyle-disc relationship. Although this may sound relatively easy, it has not proven to be so. During the past 40 years the dental profession’s attitude toward the management of disc derangement disorders has changed greatly. In the early 1970s Farrar47 introduced the concept of the anterior positioning appliance (Figure 13-5). This appliance provides an occlusal relationship that requires the mandible to be maintained in a forward position. The appliance positions the mandible in a slightly protruded position in an attempt to reestablish the more normal condyle-disc relationship. This is usually achieved clinically by monitoring the clicking joint. The least amount of anterior positioning of the mandible that will eliminate the joint sound is selected.

Although eliminating the click does not always denote successful reduction of the disc,48 it is a good clinical reference point for beginning therapy. Earlier authors recommended using arthrography,48 computed tomography,49 and more recently magnetic resonance imaging50 to assist in establishing the optimal condyle-disc relationship for appliance fabrication. Although there is little doubt that these are more precise techniques, most clinicians do not find it practical to use them on a routine basis.

The idea behind the anterior positioning appliance was to reposition to condyle back on the disc (“recapture the disc”). It was originally suggested that this appliance be worn 24 h a day for as long as 3 to 6 months. Although this appliance is still helpful in managing certain disc derangement disorders, the manner in which it is used has changed considerably following the results of long-term studies. The precise use of this appliance is discussed later in this section and its fabrication is described in Chapter 15.

When anterior positioning appliances were first used, it was discovered that they were immediately helpful in reducing painful joint symptoms by improving the condyle-disc relationship, which reduced loading on the retrodiscal tissues. When the appliance successfully reduced symptoms, a major treatment question became “What next?” Some clinicians believed that the mandible had to be permanently maintained in this forward position. Dental procedures were suggested to create an occlusal condition that maintained the mandible in this therapeutic position.51,52 Accomplishing this task was never a simple dental procedure, and questions arose regarding joint stability at this position.53 Others felt that once the discal ligaments were repaired, the mandible should be returned to the musculoskeletally stable position and that the disc would remain in proper position (that is, it would be recaptured). Although one approach is more conservative than the other, neither can be supported with long-term data.

In early short-term studies54–60 the anterior positioning appliance proved to be much more effective in reducing intracapsular symptoms than the more traditional stabilization appliance. This, of course, led the profession to believe that returning the disc to its proper relationship with the condyle was an essential part of treatment. The greatest insight regarding the appropriateness of a treatment modality, however, is gained from long-term studies. Forty patients with various derangements of the condyle-disc complex were evaluated56 2.5 years after anterior positioning therapy and step-back procedures. None received any occlusal alterations. It was reported that 66% of the patients were found to still have joint sounds, yet only 25% were still experiencing any pain. If, in this study, the criterion for success was the elimination of pain and joint sounds, then success was achieved in only 28%. If the presence of asymptomatic joint sounds is not a sign of treatment failure, however, the success rate for anterior positioning appliances rises to 75%. Other long-term studies38,61 have reported similar findings. The issue that must be addressed, therefore, is the relative clinical significance of asymptomatic joint sounds.

As already stated, joint sounds are very common in the general population. In most cases62–68 they do not appear to be related to pain or decreased joint mobility. If all clicking joints always progressed to more serious disorders, then this would be a good indication that each and every joint that clicked should be treated. The presence of unchanging joint sounds over time, however, indicates that structures can often adapt to less than the best functional relationships. To understand the need for treatment, one must compare long-term studies of untreated joint sounds.

Greene et al69 reported on 100 patients with clicking joints who were reevaluated 5.2 years after receiving conservative therapy for masticatory muscle disorders. Of the total, 38% no longer had joint sounds; of these 38%, only one (1%) had increased joint pain. In a similar study, Okeson and Hayes70 reported on 84 patients with TMJ sounds who were reevaluated 4.5 years after receiving conservative therapy for masticatory muscle disorders. None of these patients was treated for their joint sounds. At the end of that study, a similar 38% no longer had joint sounds, whereas 7.1% felt that their symptoms were increased. In a study by Bush and Carter,71 35 students entering dental school had joint sounds, but only 11 (or 31%) had them 3.2 years later, at graduation. It was also noted in this study that of 65 dental students entering without joint sounds, 43 (or 66%) graduated with sounds.

In another very interesting study by Magnusson et al,72 joint sounds were reported in a 15-year-old population and then again in the same population at age 20. Of the 35 subjects who initially had sounds, 16 (or 46%) did not have them at age 20. The subjects were not given any treatment. Furthermore, of the 38 subjects who did not have joint sounds initially, 19 (or 50%) did have them at age 20. This study therefore implies that a 15-year-old with TMJ sounds has a 46% chance that the sound will go away without treatment by age 20. The study also suggests, however, that if a 15-year-old does not have TMJ sounds, there is a 50% chance that he or she will have them by age 20. The authors concluded that joint sounds come and go and are often unrelated to major masticatory symptoms. Follow-up examinations 10 and 20 years later of this same population by Magnusson and colleagues continue to reveal the lack of a significant relationship between joint sounds and pain or dysfunction.67,73

In a similar study, Kononen et al11 observed 128 young adults longitudinally over 9 years at ages 14, 15, 18, and 23 years of age. They reported that although clicking did increase significantly with age from 11% to 34%, there was no predictable pattern and only 2% of subjects showed consistent findings during the periods of evaluation. No relationship between clicking and the progression to locking was found.

A significant long-term study by de Leeuw et al74 found that 30 years after nonsurgical management of intracapsular disorders, joint sounds persisted in 54% of the patients. Although these findings reveal that joint sounds remain in many patients, none of these patients was experiencing any discomfort or even dysfunction from their joint condition. This study, like the others referenced here, suggests that joint sounds are often not associated with pain or even major TMJ dysfunction. This research group75,76 also found that long-term osseous changes in the condyle were commonly associated with disc dislocation without reduction and not so commonly associated with disc dislocation with reduction. Yet little pain and dysfunction were noted even in the patients with significant alterations in condylar morphology (osteoarthrosis).77

Studies such as these bring into question the idea that not all joint sounds are progressive and require treatment. Several studies9,11,61,78–80 report that progression of intracapsular disorders as determined by joint sounds occurs in only 7% to 9% of patients with sounds. In another study, progression to joint locking was rare.81 It appears, however, that if the disc derangement disorder results in significant catching or locking, the chances that the disorder will progress is much greater.82

In order for a clinician to confidently recommend that TMJ sounds should be treated, he or she should first understand the rate of success for such treatment. Long-term studies reveal some enlightening information. Adler83 gave 10 patients with disc derangement disorders an anterior positioning appliance and found that it eliminated their joint sounds. After a time, 5 received fixed prostheses in the therapeutic position and 5 were stepped back to their original occlusion. Both groups showed a 40% recurrence of joint sounds. In the Moloney and Howard study,38 43% of the patients who received fixed prostheses experienced a return of joint sounds. Tallents et al84 found similar results with fixed overlays. When orthodontic therapy was used, 50% of the patients experienced a return of the click.38,85 Even with surgical procedures, it has been found86,87 that clicking returns within 2 to 4 years between 30% and 58% of the time. These studies all suggest that even when treatment is directed toward the elimination of TMJ sounds, success is not very favorable.

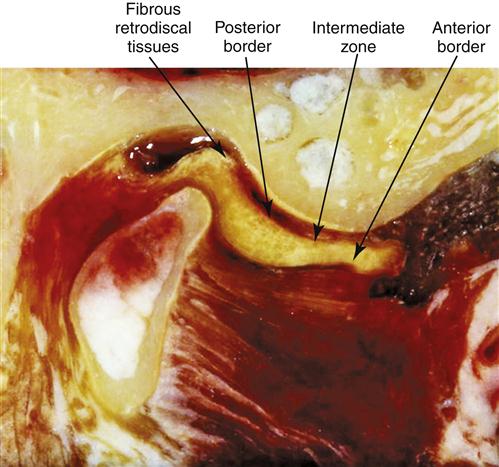

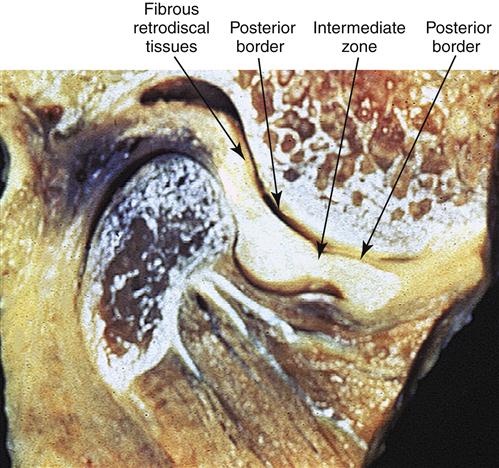

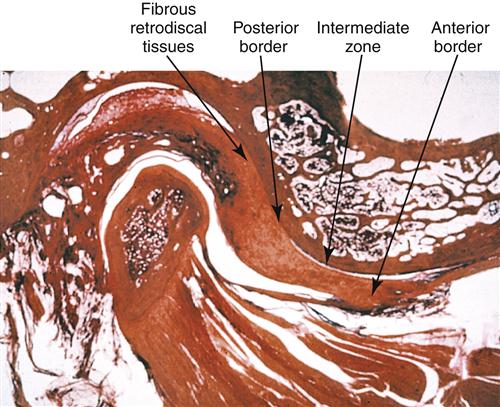

The long-term studies reveal that anterior positioning appliances are not as effective as once thought for joint dysfunction. Yet they do appear to be helpful in reducing painful symptoms associated with disc displacements and dislocations with reduction in 75% of the patients. Joint sounds appear to be much more resistant to therapy and do not always indicate a progressive disorder. These studies give us insight as to how the joint responds to anterior positioning therapy. In many patients, advancing the mandible forward for a period of time prevents the condyle from articulating with the highly vascularized, well-innervated retrodiscal tissues. This is the likely explanation for an almost immediate reduction of intracapsular pain. During the forward positioning, the retrodiscal tissues undergo adaptive and reparative changes. These tissues can become fibrotic and avascular.88–98 This is demonstrated in the gross specimens depicted in Figures 13-6 and 13-7 as well as the histologic findings in Figure 13-8.

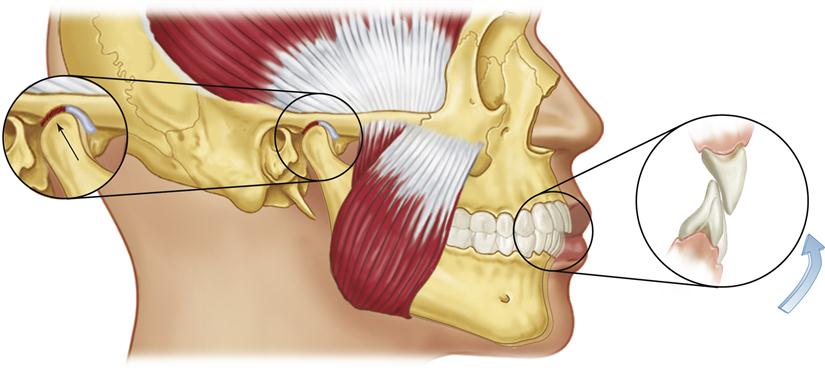

We know now that discs are not permanently recaptured by anterior positioning appliances.99–101 Instead, as the condyle returns to the fossa, it moves posteriorly to articulate on the adaptive retrodiscal tissues. If these tissues have adapted adequately, loading can occur without pain. The condyle now functions on the newly adapted retrodiscal tissues although the disc is still anteriorly displaced. The result is a painless joint that may continue to click with condylar movement (Figure 13-9). At one time it was held that the presence of joint sounds indicated treatment failure. Studies have given the profession new insight regarding success and failure. We, like our orthopedic colleagues, have learned to accept that some dysfunction is likely to persist once joint structures have been altered. Taking steps to control pain while allowing joint structures to adapt appears to be the most important role of the therapist.

A few long-term studies52,84,102 do support the concept that permanent alteration of the occlusal condition can be successful in controlling most major symptoms. This treatment, however, requires a considerable amount of dental therapy, and one must question the need when natural adaptation appears to work well for most patients. Dental reconstruction of the mouth or orthodontic therapy should be reserved for those patients who present with a significant orthopedic instability.

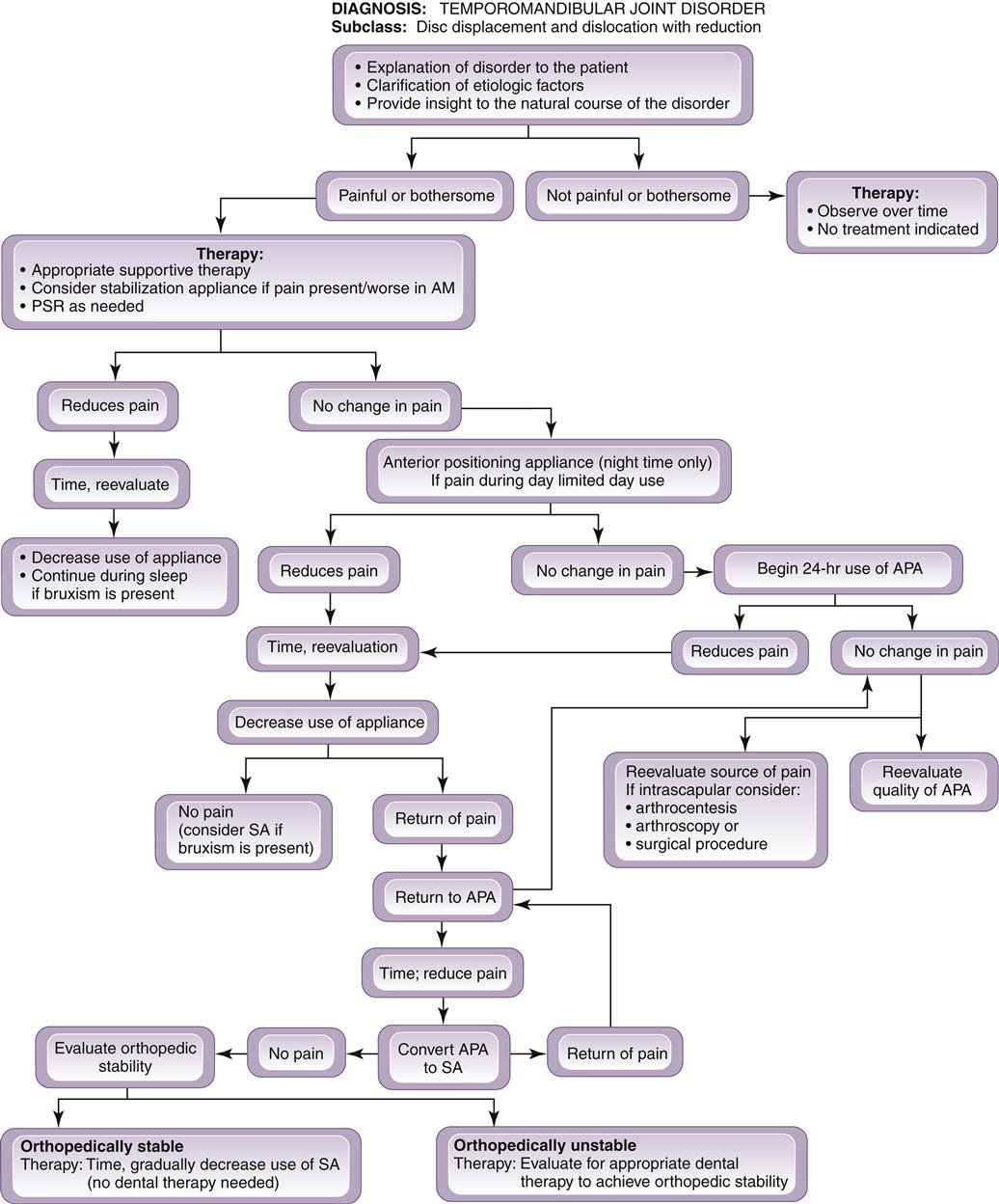

The continuous use of anterior positioning appliance therapy is not without consequence. A certain percentage of patients who wear these appliances may develop a posterior open bite. Such a bite is initially the result of a reversible myostatic contracture of the inferior lateral pterygoid muscle. When this condition occurs, a gradual relengthening of the muscle can be accomplished by converting the anterior positioning appliance to a stabilization appliance, which allows the condyles to reassume the musculoskeletally stable position. This can also be accomplished by slowly decreasing use of the appliance. A treatment sequence to accomplish this is provided in Figure 13-10.

The degree of myostatic contracture that develops is likely to be proportional to the length of time the appliance has been worn. As already mentioned, when these appliances were first introduced, it was suggested that they be worn 24 hours a day for 3 to 6 months. With this 24-hour use, the development of a posterior open bite was common. The present philosophy is to reduce the time the appliance is being worn so as to limit the adverse effects on the occlusal condition. For most patients, full-time use is not necessary to reduce symptoms. The patient should be encouraged to wear the appliance only at night to protect the retrodiscal tissues from heavy loading during sleep-related bruxism. During the day the patient should not wear the appliance, so that the mandible will be allowed to return to its normal musculoskeletally stable position. In most instances this will allow a controlled loading of the retrodiscal tissue during the day, which will enhance the fibrotic response of the retrodiscal tissues. If the symptoms can be adequately controlled without daytime use, myostatic contracture is avoided. This technique is appropriate for most patients; however, if significant orthopedic instability exists, symptoms may not be controlled.

If the symptoms do persist with only nighttime use, the patient may have to wear the appliance more often. Daytime use may be necessary for a few weeks. As soon as the patient becomes symptom-free, the use of the appliance should gradually be reduced. If reduction of use creates a return of symptoms, two possible explanations must be considered. The first and most common is that the time allowed for tissue repair has not been adequate. In this instance the anterior positioning appliance should be reinstituted and more time given for tissue adaptation. This additional time will allow more complete adaptation. Eventually it should be possible to eliminate the appliance without a return of pain.

When repeated attempts to eliminate the appliance fail to control symptoms, orthopedic instability should be suspected. When this occurs, the anterior positioning appliance should be converted to a stabilization appliance, which will allow the condyle to return to the musculoskeletally stable position. Once the condyles are in the musculoskeletally stable position, the occlusal condition should be assessed for orthopedic stability. This evaluation process will be discussed more completely in later chapters.

Numerous factors determine the length of time an appliance must be worn. These factors often relate to the amount of time necessary for the retrodiscal tissues to adapt adequately. When the main etiologic factor is macrotrauma, the duration and success of appliance therapy depend on four conditions:

Patients must be treated individually according to their unique circumstances. As a general rule the therapist should keep in mind that fewer complications occur when the appliance is used for shorter periods of time.

In some patients posterior open bites may result even after careful use of the appliance. For these patients the condyle does not return to its pretreatment position in the fossa. The reason for this phenomenon is not well documented. One explanation is the development of a myofibrotic contracture of the inferolateral pterygoid muscle. This condition creates a permanent shortening of the muscle length. Myofibrotic contracture may occur secondary to either inflammation or actual trauma to muscle tissues. A second possible explanation is the formation of very thickened retrodiscal tissues, which would disallow complete seating of the condyle in the fossa.

A third explanation for the development of a posterior open bite is a preexisting orthopedic instability, as just discussed. Perhaps the pretherapy occlusal position did not allow the condyle to be seated into the musculoskeletally stable position. Once the appliance was placed, the teeth contacting the appliance determined the condylar position. The appliance initially positioned the condyle forward and then later stepped it back to a stable condylar position in the fossa. For a patient who presents with a preexisting unstable relationship between the occlusal position and the condylar position, removal of the appliance may allow the condyle to be seated into a more musculoskeletally stable position. In this position the teeth may not occlude soundly in the preappliance position. For this patient, stepping back the appliance allows the relationship between the condyle and fossa to determine the mandibular position and not the occlusion. If the patient were allowed to immediately function without the appliance, the elevator muscles would likely drive the teeth together, redisplacing the condyle from the stable relationship in the fossa and the disc derangement disorder would return. When this condition exists, dental therapy is indicated to secure a stable occlusal position in the stable joint position (orthopedic stability). In this condition the condyle is not located down the articular eminence but in a stable position in the fossae.

None of the previous three explanations is supported by scientific documentation. Studies are needed to determine the cause of a posterior open bite secondary to long-term anterior positioning therapy. It is also important to note that a posterior open bite is not the rule but the exception and is usually a problem only if the patient has used an anterior positioning appliance continuously and for a prolonged period of time. In our experience the majority of patients can be successfully returned to their original occlusal position.

It is clear that anterior positioning appliance therapy can be effective in reducing symptoms associated with certain disc derangement disorders; however, dental instability can be a consequence. This type of therapy should therefore be used with discretion. For some patients with these disorders, a stabilization appliance can reduce symptoms,55,103 probably because a decrease in muscle activity (e.g., due to bruxism or clenching) reduces forces applied to the retrodiscal tissues. When a stabilization appliance reduces symptoms, it should be used instead of an anterior positioning appliance, since this appliance rarely leads to irreversible occlusal changes. When an anterior positioning appliance is needed, the patient should be advised that dental therapy may be necessary following use of the appliance. Although this is not very common, the patient should be well informed of the possible complications.

It should be noted that once the retrodiscal tissues have adapted and the pain symptoms have resolved, the disc is not in its original position; it is still displaced. However, in most patients the teeth will be occluding, sounding in the musculoskeletally stable position. Some clinicians may be uneasy with the concept that the disc is not in its original (normal) position. By studying the natural course of these disorders, it can be concluded that this is how nature adapts this joint. This explains why between 26% and 38% of magnetic resonance images (MRIs) in normal asymptomatic individuals reveal some disc displacement.104–111 If the disc displacement is slight and gradual, the adaptive process can occur in the absence of pain and dysfunction. Once nature has adapted this joint, we clinicians must be comfortable with this concept, even when restorative procedures are indicated. The restorative procedures should be completed in a musculoskeletally stable position with the adapted disc position. The musculoskeletally stable position is determined by the muscle function, not disc position.

Summary of definitive treatment of disc displacements and disc dislocations with reduction

The reasonable goal of definitive therapy for disc displacements and disc dislocations with reduction is to reduce intracapsular pain, not to recapture the disc. A stabilization appliance should be used whenever possible, because adverse long-term effects to the occlusion are thus minimized. When this appliance is not effective, an anterior positioning appliance should be fabricated. The patient should be initially instructed to wear the appliance always at night during sleep and during the day only when needed to reduce symptoms. This part-time use will minimize adverse occlusal changes. The patient should be encouraged to wear the appliance more only if it is the only way the pain can be controlled. As symptoms resolve, the patient is encouraged to decrease use of the appliance. With adaptive changes, most patients can gradually reduce use of the appliance with no need for any dental changes. These adaptive changes may take 8 to 10 weeks or even longer.

When elimination of the appliance produces a return of symptoms, two explanations should be considered. First, the adaptive process is not complete enough to allow the altered retrodiscal tissues to accept the functional forces of the condyle. When this is the case, the patient should be given more time with the appliance for adaptation. The second reason for a return of pain is that there is a lack of orthopedic stability and removal of the appliance brings the patient back to his or her preexisting orthopedic instability. When orthopedic instability is present, dental therapy to correct this condition may be considered. This is the only condition that requires dental therapy and in our opinion rarely occurs. A sequence of this treatment is presented in Figure 13-10.

Supportive therapy

The patient should be informed and educated to the mechanics of the disorder and the adaptive process that is essential for successful treatment. The patient must be encouraged to decrease loading of the joint whenever possible. Softer foods, slower chewing, and smaller bites should be promoted. The patient should be told, when possible, not to allow the joint to click. If inflammation is suspected, an NSAID should be prescribed. Moist heat or ice can be used if the patient finds either helpful. Active exercises are not usually helpful, since they cause joint movements that often increase pain. Passive jaw movements may be helpful; on occasion, distractive manipulation by a physical therapist may assist in healing.

Even though this is an intracapsular disorder, physical self-regulation (presented as PSR in Chapter 11) techniques should assist the patient’s recovery. The patient should be told not to allow the teeth to touch unless he or she is chewing, swallowing, or speaking. These techniques reduce loading to the joint and generally downregulate the central nervous system (CNS). These techniques help decrease pain and improve the patient’s coping skills.

Patient information sheets are provided in Chapter 16. They can be given to patients when they leave the clinic to enhance their understanding of their problems. These sheets also offer information that can help patients help themselves.

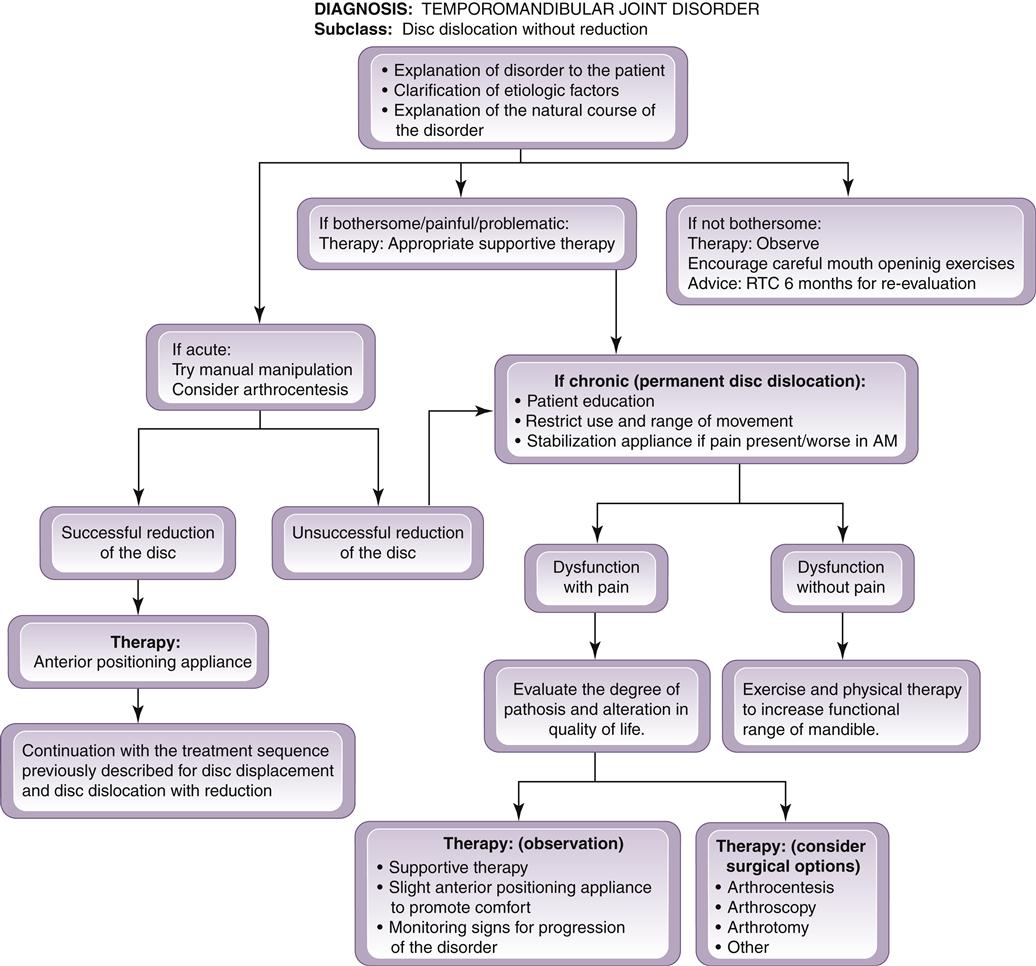

Disc Dislocation without Reduction

Disc dislocation without reduction is a clinical condition in which the disc is dislocated, most frequently anteromedially, to the condyle and does not return to normal position with condylar movement.

Etiology

Macrotrauma and microtrauma are the most common causes of disc dislocation without reduction.

History

Patients most often report the exact onset of this disorder. A sudden change in range of mandibular movement occurs that is very apparent to the patient. The history may reveal a gradual increase in intracapsular symptoms (clicking and catching) prior to the dislocation. Most often joint sounds are no longer present immediately following the disc dislocation.

Clinical characteristics

Examination reveals limited mandibular opening (25 to 30 mm) with some slight deflection to the ipsilateral side during maximal opening. There is normal eccentric movement to the ipsilateral side and restricted eccentric movement to the contralateral side.

Definitive treatment

In both displacements and dislocations with reduction the anterior positioning appliance therapeutically reestablishes the normal condyle-disc relationship. An anterior positioning appliance for a patient with a disc dislocation without reduction, however, will only aggravate the condition by forcing the disc even more forward. Therefore an anterior positioning appliance is contraindicated for such a patient. Patients who present with a disc dislocation without reduction (Figure 13-11) must be managed differently.

When the condition of disc dislocation without reduction is acute, the initial therapy should include an attempt to reduce or recapture the disc by manual manipulation. This manipulation can be very successful with patients who are experiencing their first episode of locking. In these patients there is a great likelihood that tissues are healthy and the disc has not morphologically changed. If the disc has maintained its original shape (thinnest in the intermediate zone and thicker both anteriorly and posteriorly), there is some hope that if the disc is repositioned, it will have some ability to remain in its normal position. However, once the disc has lost its normal morphology (flat throughout), the chances of maintaining the disc in place become remote. Patients with a long history of locking are likely to present with discs and ligaments that have undergone changes, and these will make it difficult for the clinician to reduce and maintain the proper disc position. As a general rule, when patients report a history of being locked for a week or less, manipulation is often successful. In patients with a longer history, success begins to decrease rapidly.

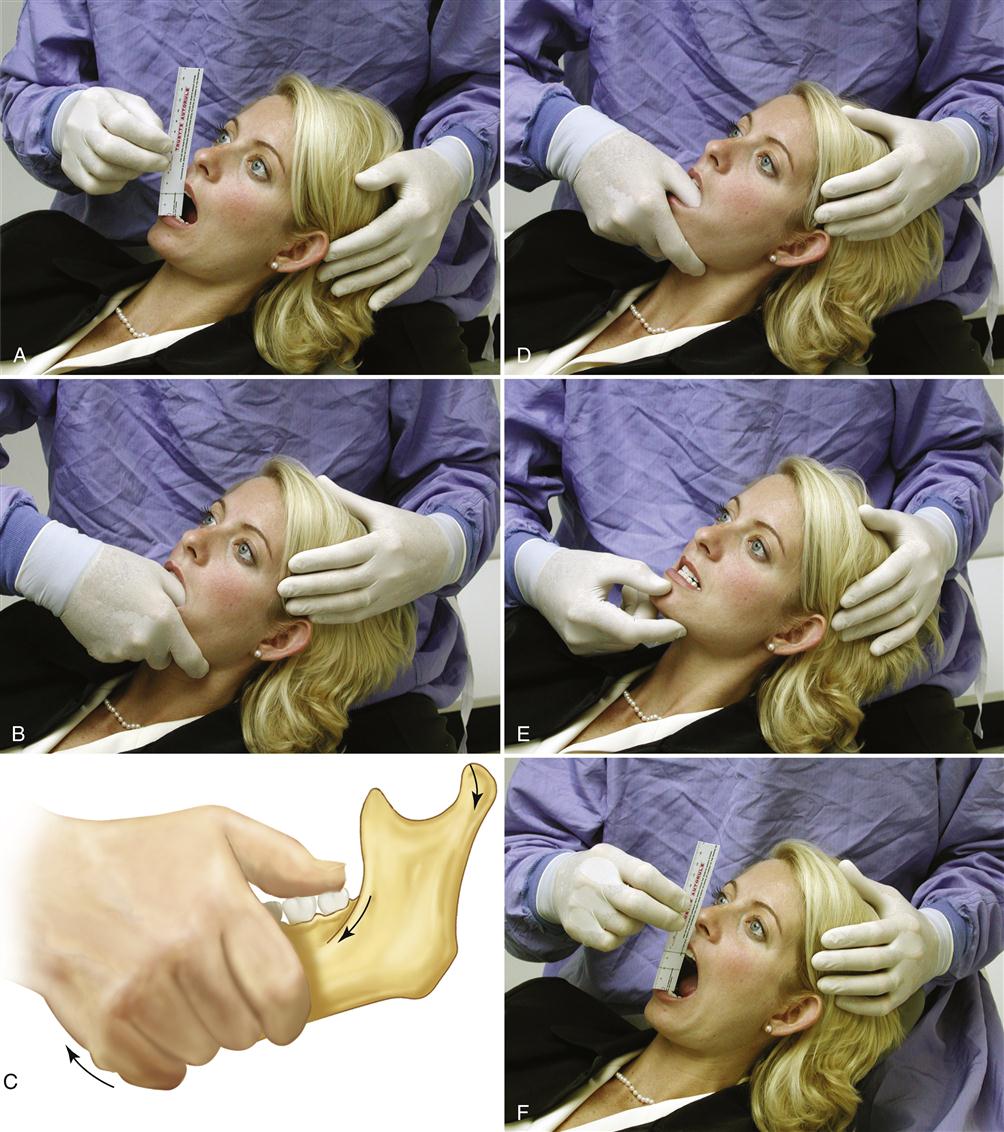

Technique for manual manipulation

The success of manual manipulation for the reduction of a dislocated disc will depend on three factors. The first is the level of activity in the superior lateral pterygoid muscle. This muscle must be relaxed to permit successful reduction. If it remains active because of pain, it may have to be injected with local anesthetic prior to any attempt to reduce the disc. Second, the disc space must be increased so the disc can be repositioned on the condyle. When increased activity of the elevator muscles is present, the interarticular pressure is increased, making it more difficult to reduce the disc. The patient must be encouraged to relax and avoid closing the mouth forcefully. The third factor is that the condyle must be in the maximal forward translatory position. The only structure that can produce a posterior or retractive force on the disc is the superior retrodiscal lamina; if this tissue is to be effective, the condyle must be in the forward most position.

The first attempt to reduce the disc should begin by having the patient attempt to self-reduce the dislocation. With the teeth slightly apart, the patient is asked to move the mandible to the contralateral side of the dislocation as far as possible. From this eccentric position the mouth is opened maximally. If this is not successful at first, the patient should attempt this several times. If the patient is unable to reduce the disc, assistance with manual manipulating is indicated. The thumb is placed intraorally over the mandibular second molar on the affected side. The fingers are placed on the inferior border of the mandible anterior to the thumb position (Figure 13-12). Firm but controlled downward force is then exerted on the molar at the same time that upward force is placed by the fingers on the anterior inferior broader of the mandible. The opposite hand helps stabilize the cranium above the joint that is being distracted. While the joint is being distracted, the patient is asked to assist by slowly protruding the mandible, which translates the condyle downward and forward out of the fossa. It may also be helpful to bring the mandible to the contralateral side during the distraction procedure, since the disc is likely to be dislocated anteriorly and medially and a contralateral movement will move the condyle into it better.

Once the full range of laterotrusive excursion has been reached, the patient is asked to relax while 20 to 30 s of constant distractive force is applied to the joint. The clinician needs to be sure that unusual heavy forces are not placed on the uninvolved joint. One would certainly not want to injure a healthy joint while trying to improve the condition of the other joint. The patient should always be asked if he or she is feeling any discomfort or strain in the uninvolved joint. If there is discomfort, the procedure should be immediately stopped and begun again with the proper directional force placed. A correctly performed manual manipulation to distract a TMJ should not jeopardize the healthy joint.

Once the distractive force has been applied for 20 to 30 s, the force is discontinued and the fingers are removed from the mouth. The patient is then asked to lightly close the mouth to the incisal end-to-end position on the anterior teeth. After relaxing for a few seconds, the patient is asked to open wide and return to this anterior position (not maximum intercuspation). If the disc has been successfully reduced, the patient should be able to open to the full range (no restrictions). When this occurs, the disc has likely been reduced and an anterior positioning appliance is immediately placed to prevent clenching on the posterior teeth, which would likely redislocate the disc. At this point, the patient has a normal condyle-disc relationship and should be managed in the same manner as discussed for the patient with a disc dislocation with reduction with one exception.

When an acute disc dislocation has been reduced, it is advisable to have the patient wear the anterior positioning appliance continuously for the first 2 to 4 days before beginning only nighttime use. The rationale for this is that the dislocated disc may have become distorted during the dislocation, which may allow it to be redislocated more easily. Maintaining the anterior positioning appliance in place constantly for a few days may help the disc reassume its more normal shape (thinnest in the intermediate band and thicker anterior and posterior). If the normal morphology is present, the disc will be more likely maintained in its normal position. However, if this disc has permanently lost it normal morphology, it will be difficult to maintain its position. This is why manual manipulations for disc dislocations are attempted only in acute conditions when the likelihood of normal disc morphology exists.

If the disc is not successfully reduced, a second and possibly a third attempt can be attempted. Failure to reduce the disc may indicate a dysfunctional superior retrodiscal lamina or a general loss of disc morphology. Once these tissues have changed the disc dislocation is most often permanent.

If the disc is permanently dislocated, what types of treatments are indicated? This question has been asked for many years. At one time it was felt that the disc needed to be in its proper position for health to exist. Therefore, when the disc could not be restored to proper position, a surgical repair of the joint appeared to be necessary. Over years of studying this condition we have learned that surgery may not be needed for most patients. Studies81,112–123 have revealed that over time, many patients achieve relatively normal joint function even with the disc permanently dislocated. With these studies in mind it, would seem appropriate to follow a more conservative approach that would encourage adaptation of the retrodiscal tissues. Patients with permanent disc dislocation should be given a stabilization appliance that will reduce forces to the retrodiscal tissues, especially if sleep-related bruxism is present.103 Only when this and the supportive therapies fail to reduce pain should more aggressive procedures, such as surgery, be considered. (The indications for these more aggressive procedures are discussed later in this chapter.)

Supportive therapy

Supportive therapy for a permanent disc dislocation should begin with educating the patient about the condition. Because of the restricted range of mouth opening, many patients will try to force their mouths to open wider. If this is attempted too strongly, it will only aggravate the condition of the intracapsular tissues, producing more pain. Patients should be encouraged not to open too wide, especially immediately following the dislocation. With time and tissue adaptation, they will be able to return to a more normal range of motion (usually greater than 40 mm).113–120 This return to a more normal range of mouth opening is part of the natural course of this disorder even though the disc maintains its forward dislocated position. Gentle, controlled jaw exercise may be helpful in regaining normal mouth opening,124–127 but care should be taken not to be too aggressive, as this may lead to more tissue injury. The patient must be told that improvement will take time, as much as a year or more for the full range.

The patient should also be told to decrease hard biting, not to use chewing gum, and generally to avoid anything that aggravates the condition. If pain is present, heat or ice may be used. NSAIDs are indicated for pain and inflammation. Joint distraction and phonophoresis over the joint area may be helpful. Providing the patient with the basic aspects of physical self-regulation can also be important in the recovery phase (Chapter 11).

Patient information sheets are provided in Chapter 16. They can be given to patients when they leave the clinic to enhance their understanding of their problems. These sheets also offer information that can help patients help themselves.

Surgical considerations for condyle-disc derangement disorders

Disc displacements and dislocations develop from alterations in the structural integrity of the condyle-disc complex. A definitive treatment that may be considered for such derangements is surgical correction. The goal of surgery should be to return the disc to a normal functional relationship with the condyle. Although this approach seems logical, it is also very aggressive. Surgery therefore should be considered only when conservative nonsurgical therapy fails to adequately resolve the symptoms and/or there is progression of the disorder and it has been adequately determined that the source of pain lies within intracapsular structures. The patient should be educated regarding the likely results of surgery and the medical risks. These factors should be weighed by the patient against his or her quality of life. The decision to undergo surgery should be made by the patient only after acquiring all the needed information.

When indications arise that the clinician must be more aggressive in treating a disc derangement disorder, the first procedure that should be considered is an arthrocentesis. In this procedure two needles are placed into the joint and sterile saline solution is passed through, lavaging the joint. This procedure is very conservative and studies suggest that it has been helpful in reducing symptoms in a significant number of patients.128–137 The lavage is thought to eliminate many of the algogenic substances and secondary inflammatory mediators that produce the pain.138 The long-term effects of arthrocentesis are positive in maintaining the patient relatively pain-free.133,134,137,139 It is certainly the most conservative “surgical procedure” that can be offered and therefore has an important role in managing intracapsular disorders.

It is common, during the arthrocentesis, to place a steroid into the joint at the completion of the procedure. Some surgeons have also suggested placing sodium hyaluronate into the joint.140–142 Although this may have some benefit, further studies are needed to determine the long-term advantage of including this treatment.143

In cases of disc dislocation without reduction, a single needle can be introduced into the joint and fluid can be forced into the space in an attempt to free the articular surfaces. This technique is called pumping the joint and may improve the success of manual manipulation for a closed lock.140,144–148

Arthrocentesis has even proven helpful for the short-term relief of rheumatoid arthritis symptoms.149 Twelve rheumatoid arthritis patients receiving arthrocentesis were statically improved for both pain and dysfunction 6 weeks postprocedure.

Another relatively conservative surgical approach for treating these intracapsular disorders is arthroscopy. With this technique an arthroscope is placed into the superior joint space and the intracapsular structures are visualized on a monitor. Joint adhesions can be identified and eliminated and the joint can be significantly mobilized. This procedure appears to be quite successful in reducing symptoms and improving range of motion.131,135,137,139,150–165 Arthroscopy does not correct the disc position; instead, success is more likely achieved by improving disc mobility.166–169

On occasion the joint must be opened for reparative procedures. Open-joint surgery is generally called arthrotomy. A variety of arthrotomy procedures can be performed. When a disc is displaced or dislocated, the most conservative surgical procedure is a discal repair or plication.170–175 During a plication procedure, a portion of the retrodiscal tissue and inferior lamina is removed and the disc is retracted posteriorly and secured with sutures.

Difficulty arises if the disc has been damaged and can no longer be maintained for use in the joint. Then the choice becomes removal or replacement of the disc. Removal of the disc is called a discectomy (sometimes meniscectomy).176–180 It leaves a bone-to-bone articulation, which is very likely to produce some osteoarthritic changes. However, these changes may not produce pain.180–182 Another choice is to remove the disc and replace it with a substitute. Early on discal implants were suggested,183 including medical Silastic, which had limited success.184 In the 1980s Proplast-Teflon discal implants were used, but considerable problems arose with the material disintegrating and producing an inflammatory reaction.185–188 Dermal189–195 temporal fascial flaps,196 fat tissue,197–199 and auricular cartilage grafts200–202 have also been used. Unfortunately the dental profession has not found a suitable permanent replacement for the articular disc, so that when removal is necessary, significant compromise in function often occurs. A predominant approach at this time is simply to remove the disc (discectomy) and allow the natural adaptation process to restore function of the joint. This appears to be a better alternative than to attempt to replace the joint with something that may actually compromise the natural adaptive process.

Surgery on the TMJ should never be performed without serious consideration of the consequences. No joint that is surgically entered can be expected to function again as normal. A certain amount of scarring, restricting mandibular movement, almost always occurs. There is also a high degree of postsurgical adhesion, probably secondary to hemarthrosis.203,204 In addition, the risks of damage to the facial nerve must not be ignored. Because all these risks are great, surgery should be reserved only for patients who do not respond adequately to the more conservative therapies. This is probably less than 5% of patients seeking treatment for intracapsular disorders.

A summary of the treatment considerations for a disc dislocation without reduction is given in Figure 13-13.

Structural Incompatibility of the Articular Surfaces

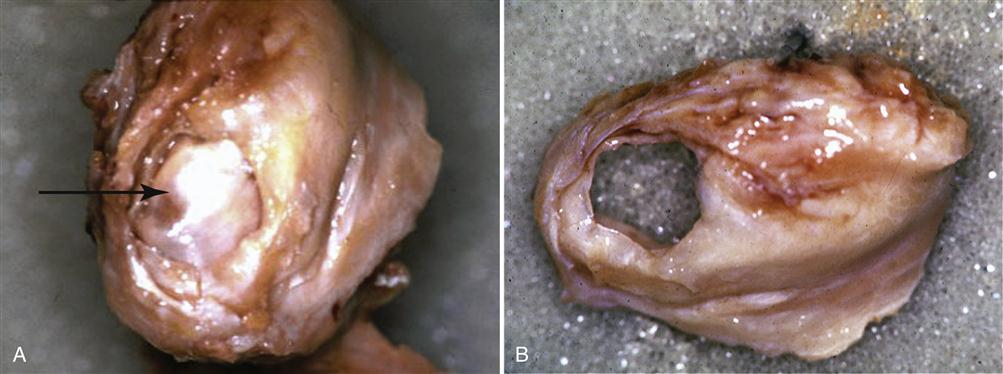

Structural incompatibility of the articular surfaces can originate from any problem that disrupts normal joint functioning. It may be trauma, a pathologic process, or merely related to excessive mouth opening. In some cases it is excessive static interarticular pressure. In others it is alterations in the bony surfaces (e.g., a spicule) or in the articular disc (a perforation) that impedes normal function (Figure 13-14). These disorders are characterized by deviating movement patterns that are repeatable and difficult to avoid.

There are four categories of structural incompatibility: deviation in form, adhesions, subluxation, and spontaneous dislocation.

Deviation in Form

Deviation in form includes a group of disorders that is created by changes in the smooth articular surface of the joint and disc. These changes produce an alteration in the normal pathway of condylar movement.

Etiology

The etiology of most deviations in form is trauma. The trauma may have been a sudden blow or the subtle trauma associated with microtrauma. Certainly loading of bony structures cause alterations in form.

History

Patients often report a long history related to these disorders. Many of these disorders are not painful and therefore may go unnoticed by the patient.

Clinical characteristics

A patient with a deviation in the form of the condyle, fossa, or disc will commonly show a repeated alteration in the pathway of the opening and closing movements. When a click or deviation in opening is noted, it will always occur at the same position of opening and closing. Deviations in form may or may not be painful.

Definitive treatment

Since the cause of deviation in form of an articular surface is actual change in structure, the definitive approach is to return the altered structure to normal form. This may be accomplished by a surgical procedure. In the case of bony incompatibility, the structures are smoothed and rounded (arthroplasty). If the disc is perforated or misshapen, attempts are made to repair it (discoplasty). Since surgery is a relatively aggressive procedure, it should be considered only when pain and dysfunction are unmanageable. Most deviations in form can be managed by supportive therapies.

Supportive therapy

In most cases the symptoms associated with deviations in form can be adequately managed by patient education. The patient should be encouraged, when possible, to learn a manner of opening and chewing that avoids or minimizes the dysfunction. Deliberate new opening and chewing strokes can become habits if the patient works toward this goal. In some cases the increased interarticular pressure associated with bruxism can accentuate the dysfunction associated with deviations in form. If this is the case, a stabilization appliance may be useful to decrease the muscle hyperactivity. However, the appliance is used only if muscle hyperactivity is suspected. If pain is associated, analgesics may be necessary to prevent the development of secondary central excitatory effects.

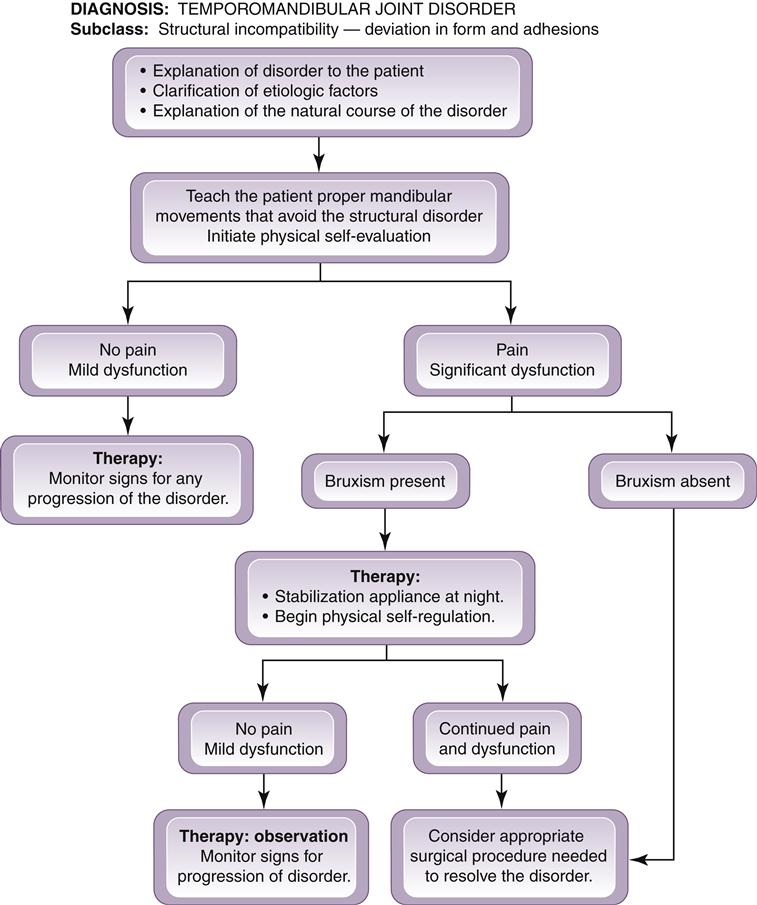

A summary of the treatment considerations for deviation in form disorders is given in Figure 13-15.

Adherences/Adhesions

Adherences represent a temporary sticking of the articular surfaces during normal joint movements. Adhesions are more permanent and are caused by a fibrosis attachment of the articular surfaces. Adherences and adhesions may occur between the disc and condyle or the disc and fossa.

Etiology

Adherences commonly result from prolonged static loading of the joint structures. If the adherence is maintained, the more permanent condition of adhesion may develop.205 Adhesions may also develop secondary to hemarthrosis caused by macrotrauma or surgery.203

History

Adherences that develop occasionally but are broken or released during function can be diagnosed only through the history. Usually the patient will report a prolonged period of time when the jaw was statically loaded (as with clenching during sleep). This period is followed by a sensation of limited mouth opening. As the patient tries to open, a single click is felt and a normal range of motion immediately returns. The click or catching sensation does not return during opening and closing unless the joint is again statically loaded for a prolonged time. These patients typically report that in the morning the jaw appears “stiff” until it is popped once and normal movement is restored.

Patients with adhesions will often report a restriction in the opening range of movement. The degree of restriction is related to the location of the adhesion. Adhesions present clinically like adherences but movement does not typically free the restriction.

Clinical characteristics

Adherences present with temporary restriction in mouth opening until the click occurs while adhesions present with a more permanent limitation in mouth opening. The degree of restriction is dependent upon the location of the adhesion. If the adhesion affects only one joint, the opening movement will deflect to the ipsilateral side. When adhesions are permanent, the dysfunction can be great. Adhesions in the inferior joint cavity cause a sudden jerky movement during opening. Those in the superior joint cavity restrict movement to rotation and thus limit the patient to 25 or 30 mm of opening. During mouth opening, adhesions between disc and fossa will tend to force the condyle across the anterior border of the disc. As the disc is thinned and the anterior capsular and collateral ligaments elongated, the condyle moves over the disc and onto the attachment of the superior lateral pterygoid muscle. In these cases the disc becomes dislocated posteriorly (Figure 13-16). The possibility of a posterior disc dislocation has been debated for some time. Evidence does exist supporting this possibility.206,207 However, it is far less common than an anterior dislocation and is more likely to be closely related to adhesions between the disc and the fossa. As mentioned in Chapter 10, a posterior dislocation will present entirely different clinical symptoms from an anterior dislocation. Often with a posterior disc dislocation, the patient opens normally but has difficulty closing and getting the teeth back into occlusion.

The symptoms associated with adhesions are constant and very repeatable. Pain may or may not be present. If pain is a symptom, it is normally associated with attempts to open the mouth which elongate ligaments.

Definitive treatment

Since adherences are associated with prolonged static loading of the articular surfaces, definitive therapy is directed toward decreasing loading to these structures. Loading may be related to either diurnal or nocturnal clenching. Diurnal clenching is best managed by patient awareness and physical self-regulation techniques (Chapter 11). When nocturnal clenching or bruxism is suspected, a stabilization appliance is indicated for decreasing the muscle hyperactivity. In some instances the articular surfaces may be roughened or abraded leading to a condition which may promote the development of adherences. The stabilization appliance will often change the relationship of these areas, lessening the likelihood of adherences.

When adhesions are present, breaking the fibrous attachment is the only definitive treatment. This can often be achieved with arthroscopic surgery (Figure 13-17).164,208–214 Not only does the surgery break up adhesions, but as previously discussed, the lavage used to irrigate the joint during the procedure assists in decreasing symptoms.

It is important to note that, since surgery is relatively aggressive, definitive treatment for adhesions should be performed only when necessary. Adhesion disorders that are painless and produce only minor dysfunction are more appropriately treated by supportive therapy.

Supportive therapy

The restriction of some adhesion problems can be improved with passive stretching, ultrasound, and distraction of the joint (Figure 13-18). These types of treatments tend to loosen the fibrous attachments, allowing more freedom for movement. Caution should be taken not to be too aggressive with the stretching technique, however, since this can tear tissues and produce inflammation and pain. In many instances, when pain and dysfunction are minimal, patient education is the most appropriate treatment. Having the patient limit opening and learn appropriate patterns of movement that do not aggravate the adhesions can lead to normal functioning (Figure 13-19).

A summary of the treatment considerations for disorders involving deviation in form is given in Figure 13-15.

Subluxation

Subluxation or, as it is sometimes called, hypermobility occurs when the condyle moves anterior to the crest of the articular eminence. It is not a pathologic condition but reflects a variation in anatomic form of the fossa.

Etiology

As just stated, subluxation is usually due to the anatomic form of the fossa. Patients who have a steep short posterior slope of the articular eminence followed by a longer flat anterior slope seem to display a greater tendency toward subluxation.215 Subluxation results when the disc is maximally rotated on the condyle before full translation of the condyle-disc complex occurs. The last movement of the condyle becomes a sudden quick jump forward, leaving a clinically noticeable preauricular depression.

History

Patients report a locking sensation whenever they open too wide. The patient can return the mouth to the closed position but often reports a little difficulty.

Clinical characteristics

During the final stage of maximal mouth opening, the condyle can be seen to suddenly jump forward with a “thud” sensation. This is not reported as a subtle clicking sensation.

Definitive treatment

The only definitive treatment for subluxation is surgical alteration of the joint itself. This can be accomplished by an eminectomy,216–219 which reduces the steepness of the articular eminence and thus decreases the amount of posterior rotation of the disc on the condyle during full translation. In most cases, however, a surgical procedure is far too aggressive for the symptoms experienced by the patient. Therefore much effort should be directed at supportive therapy in an attempt to eliminate the disorder or at least reduce the symptoms to tolerable levels.

Supportive therapy

Supportive therapy begins by educating the patient regarding the cause and the movements that create the interference. The patient must learn to restrict opening so as not to reach the point of translation that initiates the interference. On occasion, when the interference cannot be voluntarily resolved, an intraoral device (Figure 13-20) to restrict movement can be employed.220 The device is worn in an attempt to develop a myostatic contracture (functional shortening) of the elevator muscles, thus limiting opening to the point of subluxation. It is worn continuously for 2 months and then removed, allowing the contracture to limit opening.

Spontaneous Dislocation

This condition is commonly referred to as an “open lock.” It can occur following prolonged wide-open mouth procedures, as with a dental appointment. With a spontaneous dislocation, both the condyles and the discs are often dislocated out of their normal positions.

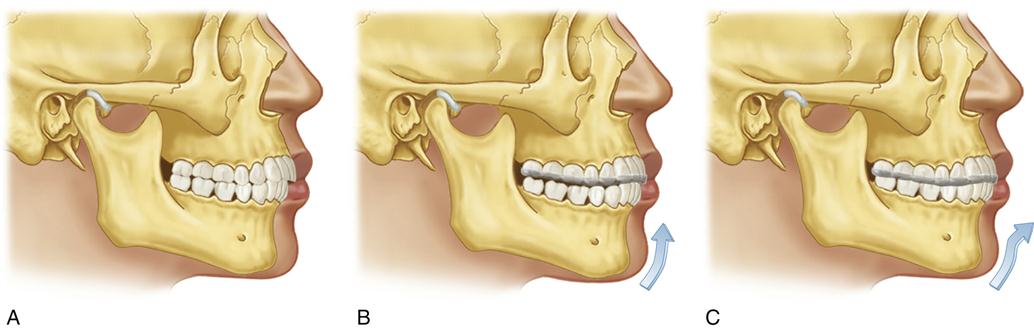

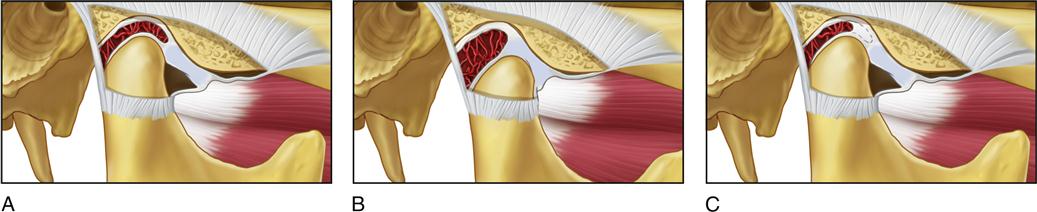

Etiology

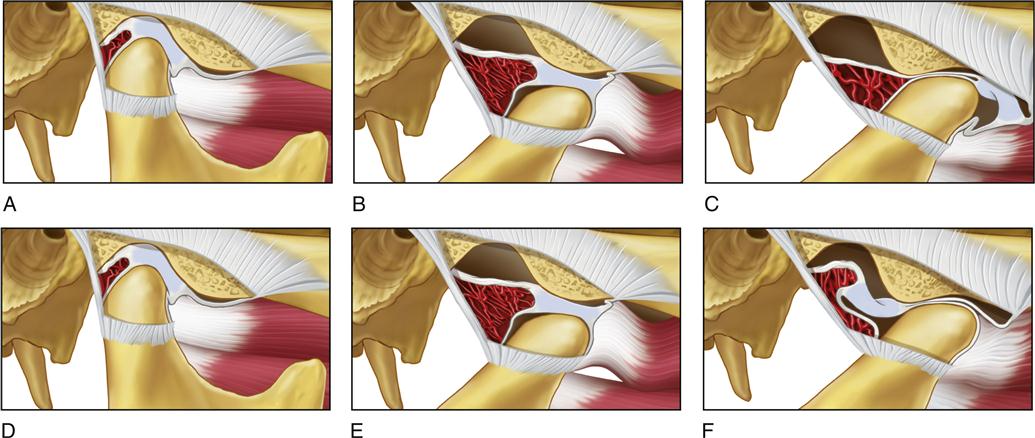

When the mouth opens to its fullest extent, the condyle is translated to its anterior limit. In this position the disc is rotated to its most posterior extent on the condyle. If the condyle moves beyond this limit, the disc can be forced through the disc space and trapped in this anterior position as the disc space collapses as a result of the condyle moving superiorly against the articular eminence (Figure 13-21, A-C). This same spontaneous dislocation can also occur if the superior lateral pterygoid contracts during the full limit of translation, pulling the disc through the anterior disc space. When a spontaneous dislocation occurs the superior retrodiscal lamina cannot retract the disc because of the collapsed anterior disc space. Spontaneous reduction is further aggravated when the elevator muscles contract, since this activity increases the interarticular pressure and further decreases the disc space. The reduction becomes even more unlikely when the superior or inferior lateral pterygoid experiences myospasms, which pull the disc and condyle forward.

Spontaneous dislocation of the TMJ can occur in any joint if the condyle is brought anterior to the crest of the eminence. Although the disc has been described as being forced anterior to the condyle, it has also been demonstrated that the disc may be trapped posterior to the condyle221 (Figure 13-21, D-F). In either condition the condyle becomes trapped in front of the eminence, resulting in the patient’s inability to close the mouth.

Although a spontaneous dislocation commonly occurs secondary to a wide mouth-opening experience, it may also be caused by sudden contraction of the inferior lateral pterygoid or infrahyoid muscles. This activity may be the result of a spasm or cramp, as discussed in earlier chapters. This condition is relatively rare and should n/>

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses