Salivary gland disease

13.1 Anatomy

Parotid gland

The parotid gland is the largest of the paired salivary glands. It occupies the region between the ramus of the mandible and the mastoid process, extending upwards to the external acoustic meatus and is essentially pyramidal in shape. The external carotid artery (deep), the retromandibular vein (intermediate) and the facial nerve (superficial) pass through the gland. The majority of the gland lies superficial to the facial nerve. Stenson’s duct runs through the cheek and drains into the oral cavity opposite the maxillary second permanent molar tooth.

13.2 Investigations

History and clinical examination

As always, symptoms are often indicative of the abnormality present. These can include:

• slowly developing swelling or mass, suggesting a tumour

• swelling (at the site of a major gland) associated with sight/taste/smell of food, slowly subsiding subsequently, suggesting obstruction

• pain and swelling (of a major gland) perhaps with a bad taste, suggesting infection

• dry mouth, suggesting a wide range of causes, including Sjögren’s syndrome.

Radiology

Is there a calculus present?

Parotid glands: Intraoral plain radiographs of the cheek (dental film placed in the buccal sulcus over the parotid orifice) and an anteroposterior radiograph of the face, with the patient requested to inflate the cheek, are required. Additional, lateral views are often taken, but any calculus may be superimposed upon bone or teeth and obscured.

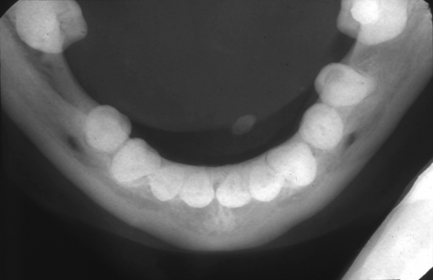

Submandibular gland: The plain radiographic examination consists of a true occlusal radiograph of the floor of the mouth (Fig. 13.1) and a ‘special’ (oblique occlusal) radiograph with the beam angled anterosuperiorly while centred on the gland itself. Lateral views may be useful, although again a calculus may be superimposed upon bone and be difficult to identify.

Is there an obstruction in the duct system? What is the condition of the duct system?

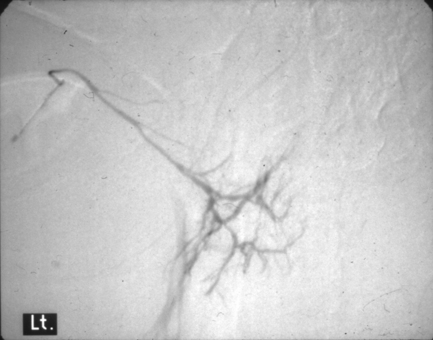

Sialography: Both these questions are best answered with sialography. Sialography is the introduction of a radio-opaque contrast medium into the orifice of one of the major salivary glands via a cannula. The media used are all iodine-containing solutions (usually low osmolarity aqueous solutions of iodine salts). The contrast is introduced slowly until discomfort is felt by the patient. Alternatively, the procedure is performed under fluoroscopic screening, allowing ‘real-time’ imaging. Usually two images are made at different angles (e.g. lateral and anteroposterior views). After this, the cannula is removed and a ‘drainage’ image obtained, usually after stimulation using a sialogogue (e.g. citric acid solution, lemon juice). Digital subtraction may be used to remove bone and tooth images, leaving the contrast image in isolation (Fig. 13.2).

Is there a mass present?

Ultrasound: This is the ‘first-line’ investigation for a mass (Fig. 13.3). A high-frequency transducer is used to obtain images in several planes of the gland. Bony superimposition may prevent complete imaging of the deep lobe of the parotid and that part of the submandibular gland immediately adjacent to the mandible. Where a lesion is completely visualised on ultrasound and where there is no suggestion of malignancy, an ultrasound examination is often sufficient for surgical planning.

Is there an abnormality of gland function?

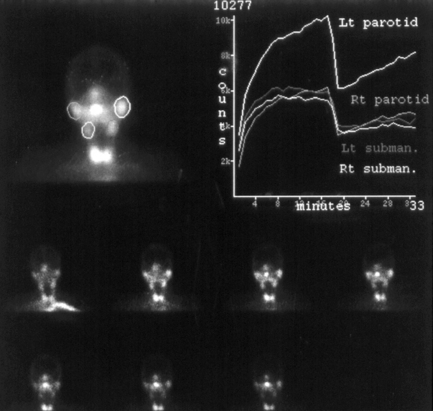

Radioisotope imaging: This is a question usually asked in relation to Sjögren’s syndrome. The only radiological technique that can assess function is radioisotope imaging (nuclear medicine). This uses a radiopharmaceutical injected intravenously. The radiopharmaceutical is a molecule containing the isotope 99 m technetium as the pertechnate (a gamma ray emitter). Once in the bloodstream, this is handled by the body in the same way as iodine and is taken up by the salivary glands and then secreted in saliva. The gamma rays are detected by a gamma camera to produce an image representing the functional activity of the glands (Fig. 13.4). It is possible to quantify activity in addition to subjective assessment of images. This technique is also employed in rare cases where aplasia of one or more major glands is suspected.

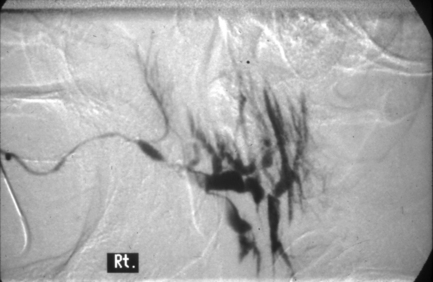

Fig. 13.4 Radioisotope scan of the salivary glands.

Each image is taken with the patient facing the gamma camera, giving a ‘face-on’ image. The highly active bilobed area of activity at the bottom of each image is the thyroid gland. In this particular patient, the problem illustrated by the quantitative study was underactivity of the right parotid. Lt, left; Rt, right; subman., submandibular.

Biopsy

On no account should a discrete salivary gland mass in a major gland be subjected to incisional biopsy, this may lead to recurrence and is usually unnecessary. For example, there is a 9 in 10 chance that a single parotid mass is a pleomorphic adenoma and so the only acceptable biopsy is a superficial parotidectomy. This will ensure removal of the tumour together with a surrounding margin of normal tissue. Fine-needle aspiration or needle core biopsy is acceptable and is without the risk of implantation of malignant cells in the needle tract. Frozen section may be useful at surgery for tumours in the parotid gland that are thought likely to be malignant, to establish whether the facial nerve may be preserved.

13.3 Salivary gland disorders

Obstructive salivary disorders

Obstructive salivary disease can be acute or chronic. The clinical features are characteristically pain and swelling of the affected gland just before meals. Astringent stimuli produce severe symptoms. Sometimes the swelling slowly subsides as saliva leaks past the obstruction, and a bad taste is suggestive of associated sialadenitis (Fig. 13.5).

Intraductal obstruction

Salivary calculus is the most common type of obstructive disorder (Fig. 13.6). The submandibular gland is most frequently involved (around 80% of cases), followed by parotid and, rarely, minor glands. The calculi (sialoliths) tend to be hard, yellowish and often have a lamellated, concentric-ring structure. They are composed of calcium phosphates, thought to be nucleated on microcalculi, which are commonly found in the major and minor glands. Salivary calculi may form in ducts within the gland substance.

Acute sialadenitis

Viral sialadenitis (mumps) is an acute contagious infection caused by a paramyxovirus. Spread is caused by direct contact with infected saliva and by droplets. There is a 2–3 week incubation period, and fever and malaise are followed by sudden, painful swelling of one or both parotid glands. In adults, viraemia results in involvement of internal organs such as the central nervous system and gonads. Orchitis (gonadal swelling) occurs in around 20% of affected adult males. Diagnosis is made on clinical grounds and bedrest is advised. As the disease occurs in minor epidemics, infected persons should avoid contact with those at risk. Virus is present in the saliva when symptoms commence and remains for approximately 6 weeks. One episode usually confers lifelong immunity.

Chronic sialadenitis

Chronic bacterial sialadenitis is related to low-grade bacterial invasion through the duct system and often follows chronic obstructive disease. The submandibular salivary gland is most commonly affected. Typically, there is recurrent, painful swelling associated with eating or drinking. The duct orifice appears inflamed and a mucopurulent discharge may be seen on examination. Patients may complain of a salty or foul taste in the mouth. The gland may become firm and fibrotic at the end stage. Pathologically there may be duct ectasia, mucous metaplasia of duct epithelium, periductal fibrosis and elastosis, acinar atrophy and a chronic inflammatory infiltration. Interlobular fibrosis results in fusion of the lobules. Surgical removal is indicated in intractable disease. On sialograms, there are combinations of sialectasis (ductal dilatation), strictures, filling defects with calculi or stagnant secretions and atrophy of minor salivary ducts (Fig. 13.7). In advanced disease, large abscess cavities may form.

Fig. 13.7 Chronic sialadenitis of the parotid gland.

The main duct has a reasonably normal diameter and course, but beyond the point of junction with an accessory gland (seen passing vertically upwards from the main duct), the gland is abnormal. The ducts are dilated and there is some atrophy of the peripheral ducts (compare with Fig. 13.1). A filling defect is visible centrally, indicating the presence of a substantial mucus plug or calculus.

Radiation sialadenitis

Radiation sialadenitis occurs mostly after radiotherapy, particularly when given for head and neck cancers. There is acinar damage and progressive fibrous replacement. Depending on dose, some recovery may be seen. The glands are shielded where possible to avoid this unwanted effect (Fig. 13.8) and techniques such as intensity modulated radiotherapy (IMRT) can be used to direct radiation and spare salivary glands. See Sjögren’s syndrome for treatment of xerostomia.

Sarcoidosis

Bilateral parotid swelling may be caused by chronic granulomatous inflammation, as part of the multisystem disorder sarcoidosis. Confluent sheets of non-caseating granulomas (aggregates of macrophages) are found in the gland parenchyma. The lacrimal glands may be involved resulting in dry eyes and mouth. Diagnosis may be made by needle core biopsy and estimating serum ACE. Referral to a physician is necessary as pulmonary lesions may be present and systemic immunosuppressive therapy is then indicated.

Sjögren’s syndrome

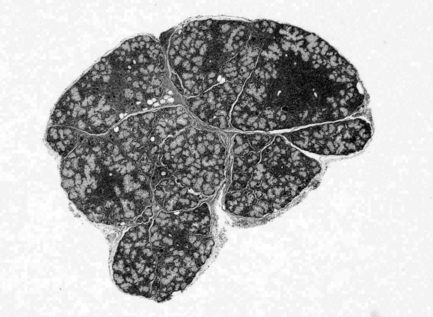

Sjögren’s syndrome is an autoimmune chronic inflammatory disease involving the salivary and lacrimal glands. It is characterised by polyclonal B-cell proliferation, probably as a result of loss of T-cell regulation. There is lymphocytic infiltration and destruction of glandular parenchyma (Fig. 13.9). Sjögren’s syndrome can have widespread manifestations and is classified into:

• primary Sjögren’s syndrome: association of xerostomia (dry mouth) and xerophthalmia (dry eyes)

• secondary Sjögren’s syndrome: association of either xerostomia or xerophthalmia and an autoimmune connective tissue disease.

There is some overlap between the two forms, though in general oral and ocular dryness is more severe in primary Sjögren’s syndrome. Widespread symptoms may be experienced in both types, including nasal and vaginal dryness, dysphagia and dry skin. Fatigue syndrome is commonly present. Autoimmune connective tissue diseases that may be associated with secondary Sjögren’s syndrome are given in Box 13.1. Rheumatoid disease (arthritis) is the most commonly associated disorder.

Diagnosis

Estimation of salivary flow (sialometry test) and lacrimal flow (Schirmer test; Fig. 13.10) are inexpensive simple tests. Often, detection of autoantibodies against Ro (SS-A) and La (SS-B) extractable nuclear antigens (ENA) can be used as reasonably sensitive and specific tests. Other autoantibodies may be detected by arranging a panel of tests, as determined by evidence-based laboratory medicine. Tests that may be utilised for the diagnosis of Sjögren’s syndrome are shown in Box 13.2. Sialographically, the classic features are varying degrees of punctate and globular sialectasis with fairly normal main ducts. However, secondary obstruction and infection means that changes often become similar to chronic sialadenitis (Fig. 13.11). There is accumulating evidence to support the role of ultrasound of the salivary glands in the diagnosis of Sjögren’s syndrome.

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses