Chapter 12

Treatment of Surgical Infections in the Orofacial Region

- Acute infections

- Diagnosis

- Bacterial investigations

- Principles of treatment of acute infections

- Infections of the face, head and neck

- Chronic infections of the jaws

Acute Infections

Acute infections of the orofacial region are due to the pathogenic activities of micro-organisms, including viruses, fungi and bacteria. Surgical infection is mainly due to bacterial infection. The progress of any infection is governed by the host response to the invading organisms. Factors related to the organism that are important include their number and virulence. Organisms vary in their virulence and can be divided into:

- commensals

- potential pathogens

- pathogens.

Commensals

These may become pathogenic by a change of site or host resistance. Host factors that are important concerning the establishment of an infection include:

- age (resistance is decreased at the extremes of age)

- concurrent disease

- drugs (immunosuppressants)

- therapeutic irradiation (this decreases the local blood supply).

Spread of Infection

Once established, infection may spread and this is governed by host and pathogen factors. Local anatomy is an important host factor in the direction of spread. There are three serious sequelae of spread of infection in the orofacial region:

- airway obstruction

- intracranial spread

- septicaemia.

Infection may spread by one of three routes:

- tissue planes and spaces

- the lymphatics

- the blood.

The prompt treatment of oral infection requires an understanding of both systemic and local factors.

Diagnosis

The diagnosis is made from the history and examination of the patient supported by additional special investigations. The five classical signs of acute inflammation are diagnostic:

- swelling

- redness

- pain or tenderness

- heat

- loss of function.

In addition, there may be a discharge of pus and regional lymphadenopathy. The systemic signs include:

- raised temperature

- rapid pulse

- general malaise.

The typical picture of the acute phase may be altered where antibacterial drugs have been ineffectively used. They may not have overcome the infection but have produced a state of balance between the invading bacteria and the patient’s defences.

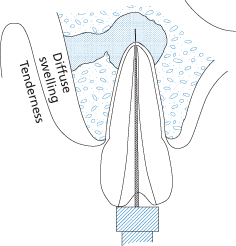

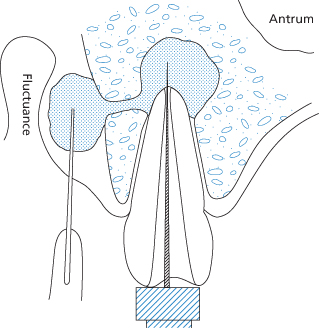

The formation of pus in a superficial abscess causes softening with fluctuation, redness and marked tenderness at the centre of the inflamed area. In a deep abscess affecting the neck, pus may spread widely and fluctuance may be masked by tense, oedematous swelling in the overlying tissue, which can be indistinguishable from cellulitis. The patient’s temperature continues to rise with a swinging temperature suggesting the presence of suppuration.

A clear and concise medical history is recorded with special regard to metabolic or blood disorders. In very acute, recurrent or persistent infections, special investigations should be performed such as:

- urinalysis

- haemoglobin

- full blood count and differential white cell count – leucocytosis

- fasting blood sugar

- blood cultures

- C-reactive protein (CRP).

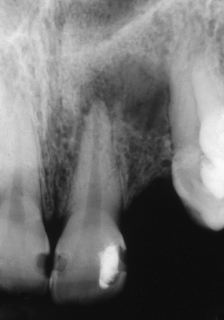

Radiographs may be uninformative in early acute infections of the jaw, unless there has been a previous chronic condition. Initially, a dental abscess may appear as a diffuse radiolucency associated with the apex of a non-vital tooth (Figure 12.1) After a period of approximately 10 days, bone changes may be seen as either localised periapical areas (Figure 12.2) or more diffuse changes in the case of osteomyelitis.

Figure 12.1 Acute periapical infection associated with a non-vital upper lateral incisor. The radiological appearance is often less marked than the history would suggest.

Figure 12.2 An established infection in a lower molar. The margins are more defined due to a long-standing chronic reaction. An acute episode may cause the patient to seek care.

The underlying cause, such as a non-vital tooth, should be sought, although treatment should not be delayed until the cause is found.

From the history the clinician should record:

- duration of infection

- changes in signs and symptoms

- sequence of events

- treatments sought, including antibiotics prescribed.

From the examination the clinician should record:

- swelling, diffuse or localised (fluctuant)

- lymphadenopathy

- trismus

- presence of sinus

- changes in the jaws and teeth

- presence of pyrexia (raised body temperature).

Bacterial Investigations

Microbiological investigation can play an important role in the management of a patient with orofacial suppurative infection. All efforts should be made to obtain an appropriate specimen for any patient suspected of having a bacterial infection. Within the laboratory the organisms will be cultured, identified and an indication given of the drugs to which the bacteria will be sensitive.

Culture and Sensitivity

This is imperative where there is:

- rapidly spreading infection

- infection in the medically compromised patient

- infection not responding to antibiotic therapy

- recurrent infection

- osteomyelitis

- postoperative infection.

Methods of Sampling

Aspiration

Where collections of pus have not discharged, aspiration is preferred to prevent loss of oxygen-sensitive strict anaerobes prior to processing. The overlying tissue is first thoroughly cleaned and dried. An 18-gauge needle in a syringe is inserted into the most dependent part of the swelling and a sample aspirated (Figure 12.3). The sample should be immediately sealed to avoid drying and contamination from the air, and sent to the laboratory accompanied by the appropriate microbiology form with the date and time of collection, nature and site of the sample, method of collection, current and previous antibiotic therapy, together with any relevant clinical information. Culture and sensitivity results should be available within 36 to 48 hours, although anaerobic cultures can take longer.

Figure 12.3 (a) Aspiration of a buccal swelling in the maxilla. (b) The aspirate is sealed into the syringe to allow anaerobic culture to proceed. An oral swab is also sent in a culture medium.

Swabs

A bacteriological swab may be used for taking pus either from an extraoral sinus or from an abscess drained through an extraoral incision, providing that the skin and surrounding area have been thoroughly cleansed beforehand. However, swabs taken inside the mouth are liable to contamination from the saliva so that growths obtained are often reported as mixed oral flora. Swabbing is the least reliable method for obtaining a specimen for culture and sensitivity, but may be required when aspiration is unsuccessful.

Principles of Treatment of Acute Infections

The management of an infection relies on general and local measures.

General Measures

The general care of patients has been discussed in Chapter 2.

Rest

Where there is an elevated temperature, the patient should rest in bed. When there is gross swelling of the neck or floor of the mouth, or the patient is toxic, they should be admitted to hospital.

Nutritional Support

Copious fluids are administered, often intravenously, to combat dehydration, which is a complication of high fever. Circulating toxins are diluted and their excretion encouraged by an increased turnover of water.

Diet

A balanced diet of easily digested proteins and carbohydrates is required (see Chapter 2).

Analgesia

Orofacial infections are painful and an important part of management is good pain control. Non-steroidal analgesics are the drugs of choice, many of which have the benefit of being anti-pyretic. In the case of airway problems, any drugs with a respiratory depressant effect, such as opioids, should be avoided.

Control of Infection

Antibacterial drugs are not always necessary in the treatment of infections. Drainage, removal of the cause and applications of heat may be enough to enable the patient to overcome the condition, and antibiotics must not be prescribed to replace or delay these local measures.

Indications for Antibiotic Therapy

- Where culture and sensitivity has been obtained

- Continuing unresponsive infection

- Systemic spread

- Chronic infections

- Postsurgical infections in medically compromised or debilitated patients

- Postoperative infections at the operative site.

Unfortunately in many of these situations it is not feasible to await the result of a culture and thus antibiotics are often prescribed blind. Amoxycillin, which is a broad spectrum penicillin, is often the preferred drug. A loading dose of 3 g amoxycillin orally rapidly achieves bactericidal concentrations in the blood, and may be followed by 250 mg or 500 mg 8-hourly. Metronidazole (200–400 mg 8-hourly) targets anaerobic bacteria, which are often the causative organisms in many dental infections. A combination of amoxycillin with metronidazole may be appropriate in more severe infections and it may be necessary to admit the patient to provide antimicrobial therapy intravenously, together with surgical drainage. Once an antibiotic has been prescribed it should not be changed within the first 48 hours unless there is bacteriological evidence of resistance. If clinical improvement is occurring despite laboratory evidence of resistance it is not essential to change the regimen. There is no set duration of administration of antibiotics and no rationale in ‘completing the course’. Antibiotic therapy should not be maintained after clinical resolution has occurred. Hyperbaric oxygen therapy is useful in promoting bone healing. It increases the effectiveness of antibiotics and the vascularity of tissues that have been subjected to radiation therapy.

Local Measures

Local measures include:

- removal of the cause

- institution of drainage

- prevention of spread

- restoration of function.

Removal of the Cause

This is the most important principle in the management of infection. In well-localised minor infections it may cure the condition immediately. In other cases it may initially be simpler to institute drainage and prevent spread. However, if the cause is not removed, infection will recur. Causes of orofacial bacterial infections include:

- necrotic pulps, periapical pathology (see Figure 12.4)

- periodontal disease

- avascular bony remnants (sequestrae)

- foreign bodies

- salivary calculi.

Figure 12.4 A necrotic pulp may be treated by opening the tooth and removing the dead pulp. The tooth can be left open to allow drainage of the collection of pus.

Once the cause has been identified it should be effectively removed, e.g. extraction of the tooth, extirpation of necrotic pulp, removal of salivary calculus, etc.

Institution of Drainage

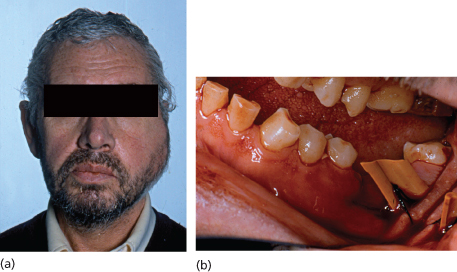

Reddening of the skin, fluctuance and a point of maximum tenderness indicate localisation of pus (pointing). When this occurs the pus must be drained and a surgical incision leaves much less scarring than if pus bursts through the skin spontaneously. To be effective, drainage must be provided at the lowest point of the abscess. A drain (see Figure 12.5) should always be inserted to keep the opening patent for as long as the discharge continues. In cellulites, drainage is not established until the condition has localised, usually after 3 or 4 days. However, where a brawny, spreading swelling of the floor of the mouth and neck might involve the larynx and jeopardise the airway, surgery will reduce the tension in the tissue spaces and should not be withheld.

Figure 12.5 Acute infection. (a) Acute painful buccal and submasseteric swelling associated with grossly carious lower molar; (b) intraoral drainage following tooth removal.

Intraoral Incisions

In the mucous membrane incisions are made parallel to the occlusal surface of the teeth, 1 to 2 cm in length, with due regard for underlying structures such as the mental nerve. Smaller incisions are ineffective. This may be performed in conjunction with pulp extirpation or extraction (Figure 12.6).

Figure 12.6 A localised swelling may be treated by opening the tooth and removing the dead pulp, together with an incision in the sulcus.

Extraoral Incisions

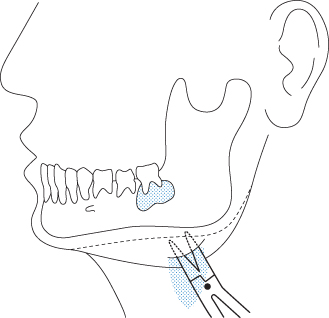

Incisions through skin should avoid the branches of the facial nerve. Where the abscess is deep and a free discharge is not obtained through a simple skin incision, Hilton’s method of blunt dissection is performed (Figure 12.7). This involves inserting closed sinus forceps into the wound, and then opening them slowly but firmly to separate the soft tissue planes; the forceps are then withdrawn open to avoid damaging nerves or vessels by closing them blind. This procedure is repeated until the abscess is reached and pus discharges. In dental infections, an area of rough cortical bone can be felt on the mandible or maxilla where the periosteum has been raised. A drain is placed to allow drainage to continue for the required duration (Figure 12.8).

Figure 12.7 Hilton’s method of drainage using sharp dissection through skin followed by blunt dissection through the tissues to open the abscess cavity.

/>

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses