12 Surgical aids to orthodontics and surgery for dentofacial deformity

ASSUMED KNOWLEDGE

It is assumed that at this stage you will have knowledge/competencies in the following areas:

MANAGEMENT OF UNERUPTED AND IMPACTED TEETH

Nowhere is the practice of dentoalveolar surgery and orthodontics more closely related than in the management of unerupted and impacted teeth. The teeth most frequently affected by failure of eruption are generally the last to erupt in a particular series—wisdom teeth, canines and second premolar teeth. The management of third molar teeth is discussed in Chapter 5.

Assessment of unerupted teeth—clinical

The timing of extractions or exposure is dependent on the age of the patient and the stage of development of the dentition. The principal treatment decision in the management of unerupted teeth is whether to extract. In general terms the rationale for removal of unerupted/malpositioned teeth resembles that for wisdom teeth (see Ch. 5). The principal indications for extraction are:

There is some evidence that timely extraction of deciduous teeth may prevent later impaction, particularly in the case of upper canines.

Assessment of unerupted teeth—radiographic

Radiographic assessment of the unerupted tooth will provide several valuable pieces of information in planning its management: stage of tooth development, crown/root morphology and angulation and the presence or absence of local disease. Most orthodontic assessment will include an orthopan-tomogram (OPT) and a lateral cephalometric view. Intraoral views are essential, however, for the management of unerupted maxillary anterior teeth due to the poor definition of the OPT in this region. In this situation, the OPT will usually be supplemented with periapical and/or upper anterior occlusal films. The use of ‘parallax’ analysis, in which two periapical views of the same area are taken from different angles (see Ch. 5), can be useful in determining whether the impacted teeth are buccal or palatal and therefore in planning the surgical approach to the teeth. In radiographic analysis, the stage of tooth development must also be carefully considered because it is inappropriate to expose teeth whose development is incomplete.

Surgical technique

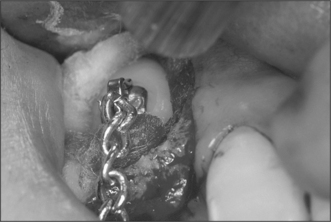

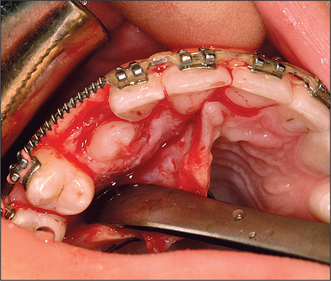

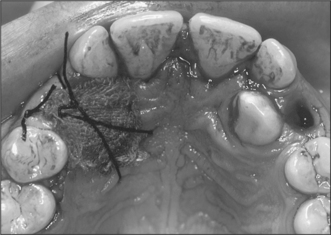

Attempts should be made to retain the keratinized tissues by employing displacement of the attached gingiva with apically or, occasionally, laterally repositioned flaps. The apically repositioned flap retains the mucogingival collar around the tooth and is displaced apically and sutured into place. The bunched gingiva will remodel as wound healing occurs (Fig. 12.1). If the tooth is misaligned, a bracket and gold chain may be etched to the canine to direct its eruptive path appropriately (Fig. 12.2).

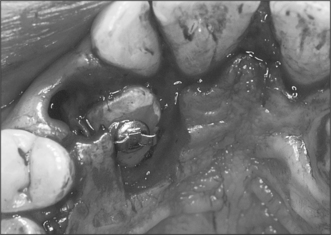

Although simple exposure is satisfactory for superficially placed teeth situated close to the surface and impacted in soft tissue alone, most unerupted teeth are located more than 3–4 mm from the oral mucosal surface and the crown cannot be seen completely after raising a flap (Fig. 12.3). As impaction of unerupted teeth usually involves hard tissue as well as soft tissue, all bone covering the tip of the crown as far as the maximum width of the tooth should be carefully removed. If the tooth is superficial and covered by thin bone this can often be undertaken using a scalpel blade. Where bone coverage of the unerupted tooth is more extensive, a small rose head bur or hand-held chisel may be used to clear overlying bone from the crown. Extreme caution must be taken to avoid damaging the tooth crown and the roots of the adjacent teeth. Unnecessary removal of bone should also be avoided. Whilst soft- and hard-tissue exposure of unerupted teeth is in some instances successful, most commonly (and especially in the case of deeply impacted teeth) the created surgical defect will become re-epithelialized if patency is not maintained. The defect is, therefore, packed with an antiseptic gauze dressing or a glass-ionomer cement bonded to the tooth crown in order to inhibit contraction and re-epithelialization (Fig. 12.4). Postoperative antibiotics are seldom indicated unless there is a known increased risk of wound infection, e.g. patients with insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus.

Mechanical traction and unerupted teeth

If the crown tip of a maxillary canine is beyond the midline of the lateral incisor root, spontaneous eruption will not usually occur and mechanical traction will be necessary. Bonding of the bracket to the tooth following its exposure (Fig. 12.5) involves a sequence of etching, washing, drying and bonding similar to that employed in conventional adhesive dentistry. Bonding is best performed in collaboration with an orthodontist to ensure the angulation and position of the bracket is appropriate in relation to the force to be applied to the tooth. During the procedure maintenance of a meticulously dry field is essential and this is facilitated by careful suction and local infiltration of epinephrine-containing local anaesthetic.

Autotransplantation and surgical repositioning of teeth

In the past, autotransplantation was a popular treatment for unerupted canine, premolar and even molar teeth but there are some considerable biological problems associated with the technique to be overcome. Although individual studies have suggested clinical and radiographic success rates as high as 80% for the transplantation (at 1–5 years following surgery), most transplanted teeth will develop evidence of root resorption or even ankylosis if they are not root-treated. The success rate of transplantation can be maximized by careful handling of the tooth and preparation of the socket with minimal trauma. Resorption is directly influenced by the extent of trauma to the periodontal tissues on the root surface and care must be taken to minimize this during the removal of the tooth. For this reason, transplantation should be undertaken only on young, medically fit patients and should exclude all teeth which will be difficult to extract or those with hooked apices which will preclude simple elevation.

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses