Premalignancy and malignancy

12.1 Potentially malignant disorders

Submucous fibrosis

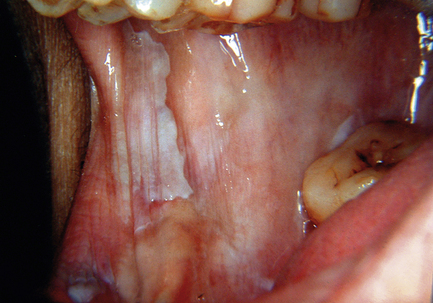

Oral submucous fibrosis is related to using paan, which is a leaf quid containing areca nut. Many types exist, including fresh products consumed in the Indian subcontinent and southeast Asia as well as packed proprietary products. Tobacco, slaked lime, spices and other ingredients may be added; in southeast Asia, areca nuts are often chewed fresh. The mucosa and teeth become stained orange–brown because paan is held in the mouth for long periods. The affected mucosa becomes pale in colour and feels firm on palpation (Fig. 12.1). Fibrous bands may develop in the buccal mucosa and a pale, constricting fibrosis typically involves the palate. Mouth opening becomes restricted and swallowing may be difficult. The risk of developing oral carcinoma has been estimated at around 5%, although the risk of submucous fibrosis itself cannot be separated from the risks posed by carcinogenic substances in paan. In biopsy material, a subepithelial band of fine fibrillary collagen is seen in the lamina propria and the oral epithelium can be reduced to only a few cell layers in thickness. Keratinisation and chronic inflammation may be present in some cases. Where areas of erythroplasia and leukoplakia are present, biopsies may show epithelial dysplasia or even carcinoma.

Leukoplakia and erythroplakia

Previously, premalignant lesions were defined as areas of morphologically altered tissue in which cancer can arise. Various terms have been used to describe these lesions and diagnosis is often made by exclusion. Many lesions do not progress to cancer and some even regress. It is probable that a proportion of lesions diagnosed as potentially malignant are actually reactive, while others do not progress within the lifetime of the patient. Discrete white or red mucosal patches are referred to leukoplakia and erythroplakia respectively. Proliferative verrucous leukoplakia (PVL) is a clinically and histologically distinctive high-risk oral lesion.

Leukoplakia

• Homogeneous leukoplakias are plaque-like lesions with a uniform smooth or wrinkled surface; there is less risk of malignant transformation.

• Non-homogeneous leukoplakias tend to be less circumscribed and show a greater range of appearances. Proliferative verrucous leukoplakia has a warty appearance and speckled leukoplakia has interspersed red areas. Heaping up of keratin, nodularity and ulceration may be present. The risk of malignant transformation is greater in non-homogeneous leukoplakia. Often these lesions are multifocal.

The risk of malignant transformation is difficult to estimate in any individual case. Lesions in the floor of mouth and ventral tongue, and those showing evidence of epithelial dysplasia or carcinoma in situ, are considered to be at high risk (Fig. 12.2). Paradoxically, the risk of malignant transformation is greater in non-smokers than in smokers. Leukoplakia is very rare in non-smokers. The regression of leukoplakia in smokers following cessation suggests that a proportion of lesions are reactive, whereas leukoplakia in non-smokers may reflect a local cellular genetic change that tends to be progressive. However, there is evidence to suggest that smoking cessation in leukoplakia reduces risk, and an appropriate intervention is advised.

Fig. 12.2 Leukoplakia of the buccal mucosa.

Other terms for leukoplakia

A variety of terms have been employed to describe leukoplakic potentially malignant oral lesions.

Sublingual keratosis: This term is applied to leukoplakia affecting the floor of mouth and ventral tongue. One reported series described a malignant transformation in over 30% but this has not been confirmed by later studies. The term is not generally favoured because of lack of evidence supporting it as a distinct entity.

Candidal leukoplakia: It is possible for Candida pseudohyphae to invade the keratin on the surface of leukoplakia and it may cause a subepithelial chronic inflammatory response. The presence of microscopic dysplasia in this lesion causes concern. Candidal leukoplakia must be distinguished from chronic hyperplastic candidiasis which results in a firm warty or specked plaque that cannot be scraped off. It occurs most commonly on the dorsal tongue and buccal mucosa behind the angle of the mouth. Staining with diastase periodic acid-Schiff’s base (DPAS) shows pseudohyphae of Candida species growing into the keratin layer, where they are typically associated with a neutrophil inflammatory infiltrate. There is marked epithelial hyperplasia with formation of elongated and blunted rete processes. Elimination of predisposing factors such as smoking, poor denture hygiene and haematinic deficiency, combined with systemic antifungal therapy, may cause resolution of the white plaque. Reactive cellular atypia may be seen, but if dysplasia is present then the lesion must be considered to be candidal leukoplakia.

Syphilitic leukoplakia: This is less relevant to contemporary practice but carried a high risk of malignant transformation when it was prevalent. It was a complication of tertiary syphilis and tended to affect the dorsum of the tongue.

Proliferative verrucous leukoplakia (PVL): The World Health Organization classification recognises this disorder as a high-risk precursor oral lesion. Typically, multifocal mucosal lesions are identified and show a warty appearance, although flat erythematous and keratotic areas may also be present. The gingivae and palate are often affected. Microscopically there may be little cytological atypia leading to underestimation of grade pathologically. Lichenoid inflammation may further obscure recognition of dysplasia. Diagnosis is made by a combination of microscopic architectural abnormality and the clinical features. Ultimately around 80% of PVL sufferers develop oral cancer and higher grade dysplasia is frequently seen in biopsies as the disease progresses.

12.2 Pathology and genetics

Epithelial dysplasia and carcinoma in situ

The term dysplasia is used in a variety of contexts in pathology and means literally ‘abnormal growth’. In the context of potentially malignant oral disorders, it refers to a combination of cytological changes and disturbances of cellular arrangements seen during the process of malignant transformation. Epithelial dysplasia is graded by oral and maxillofacial pathologists into mild, moderate and severe grades. An alternative scheme uses the term ‘squamous intraepithelial neoplasia’ (SIN 1, 2 and 3 respectively). The term carcinoma in situ is applied when abnormalities involve the entire thickness of the epithelium; in the SIN system, severe dysplasia and carcinoma in situ are combined as SIN 3. The histopathological features recognised in dysplasia are given in Table 12.1.

Table 12.1

Histopathological features of epithelial dysplasia

| Feature | Comment |

| Nuclear and cellular pleomorphism | Variation in the sizes and shapes of cells and nuclei |

| Increased nuclear/cytoplasmic ratio | Can be quantified using cytophotometry |

| Nuclear hyperchromatism | Intense staining of nuclei |

| Prominent nucleoli | May be larger than normal and/or increased in number |

| Abnormal mitotic activity | Increased mitotic rate, mitotic figures present above the suprabasal layer, abnormal forms |

| Basal-cell hyperplasia | Several layers of basal cells may be seen; may result in drop-shaped rete processes |

| Disturbance of basal-cell polarity | Basal cells lose their orientation; nuclei lose their polarity |

| Abnormal maturation | Loss of normal stratification pattern; maturation present at inappropriate levels |

| Aberrant keratinisation | May involve individual cells and may result in the formation of intraepithelial keratin pearls |

Grading of dysplasia

Studies on histopathological grading show poor kappa agreement between even specialist pathologists. This problem arises because of lack of scientific evidence for weighting the various features of dysplasia. For example, drop-shaped rete processes are generally accepted as a sinister feature, whereas increased mitotic rate may be seen in reactive processes. Both inter- and intraobserver variabilities between pathologists are high and the biological behaviour of the lesion does not always correlate with its grading. Problems may also arise because of non-representative sampling at the time of biopsy. Although histopathological grading is intrinsically unreliable, the presence of dysplasia in a suspicious lesion remains the best predictive indicator of malignant change.

Tumour suppressor genes and oncogenes

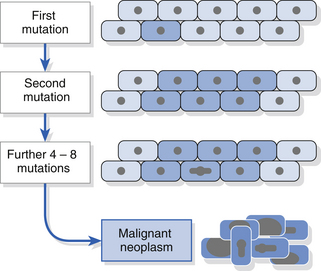

The process of malignant transformation is the result of accumulation of genetic damage. There may be genomic instability or stepwise accumulation of genetic events (Fig. 12.3). The latter process is thought to operate in most oral cancers and studies have demonstrated mutations, methylation or loss of various tumour suppressor genes (e.g. p53, p16, p21, retinoblastoma, FHIT) in oral cancers. Loss of function of a tumour suppressor gene confers a selective growth advantage on the cell, resulting in an expanded population in which further genetic abnormalities are thought to arise. Abnormal oncogene activity may increase cell proliferation rates and drive malignant progression. Dysplasia is likely to represent a histopathological change resulting from genetic alterations. Aneuploidy is a change in the number of chromosomes and is being investigated as a marker of malignant change using cytology methods.

Management of potentially malignant oral lesions

• extensive or spreading lesions

• lesions in the floor of mouth/ventral tongue, retromolar area, palate or pillar of fauces

Most important is the presence of dysplasia or carcinoma in situ (SIN 3). Management should include:

• clear information and explanation of the significance of the lesion to the patient

• intervention to stop tobacco habit and limit alcohol intake

• treat anaemia and candidal infection if present

• surgical or laser excision or drug treatment may be considered

• regular review and observation: investigation if signs of cancer appear.

12.3 Oral cancers

Most oral cancers do not arise in a clinically recognised premalignant lesion and are diagnosed as primary cancerous lesions. They are typically painless, unless infected or advanced, and often cause no symptoms. For this reason, the need to conduct a careful systematic examination for every patient cannot be stressed too much. Extraoral examination should include both visual inspection of the face and neck and palpation of the neck (see Chapter 2). The patient’s head should be tilted forwards and the lymph nodes in the neck palpated in relaxed tissue. A routine technique should be adopted, perhaps starting with the submental nodes and then moving to more posterior node groups. The oral mucosa and oropharynx should be examined carefully. The tongue should be protruded to detect lateral deviation and then relaxed and lifted to allow examination of its ventral surface and the floor of the mouth. Correct positioning and the use of good illumination and mirrors are important factors. When oral cancer is detected, prompt referral is essential. The importance of attending at the hospital should be stressed, without provoking undue anxiety. Until a biopsy result is available, definitive diagnosis should be avoided. Any ulcer that fails to heal within a 3-week period should be regarded as suspicious and the patient should be referred to a specialist.

Epidemiology

Morbidity and mortality

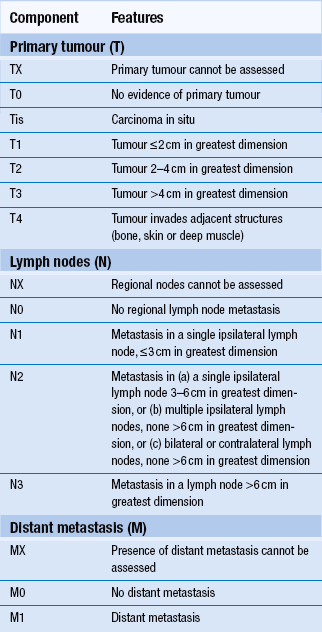

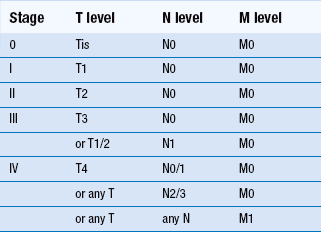

Overall 5-year survival for oral cancer is just over 50% but depends very much on the stage at initial diagnosis and clinical factors. Squamous-cell carcinoma of the lip has a better prognosis than intraoral carcinoma. In general, prognosis is worse when tumours arise in the more posterior parts of the oral cavity than in the anterior area. Midline carcinomas in the floor of the mouth and ventral tongue may, however, spread to both sides of the neck. Staging is a system used to describe the degree of spread or tumour ‘load’ and the most widely used TNM (tumour, lymph node, metastases) system is described in Tables 12.2 and 12.3. Survival at 5 years for TNM stage I oral carcinoma is around 80%, whereas survival is reduced to 15% for stage IV. Morbidity refers to the reduction in function, both physical and psychological. Again, morbidity tends to relate to stage, as large tumours may require removal of a large amount of tissue or radical radiotherapy. Hospital readmission is frequent during treatment and, in many cases, tumours prove refractory to all forms of therapy. Quality of life can be assessed and is an important measure of morbidity. Good dental health is a significant factor.

Types of oral cancer

Squamous-cell carcinoma accounts for around 95% of all oral cancers. It arises from the epithelial lining of the oral cavity. It is described in detail in the next section. A number of other forms of malignant disease also arise in the oral cavity.

Minor salivary gland cancers: These tend to occur in the palate and upper lip and they present as rubbery nodules, sometimes ulcerated and painful. They are described in Chapter 13

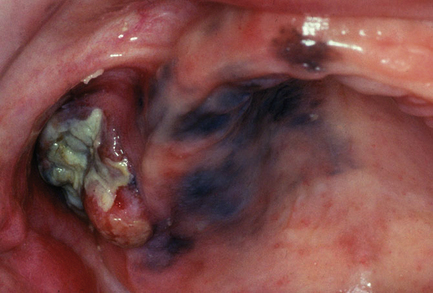

Malignant melanoma: This typically occurs in the palatal and gingival mucosa. A spreading brown-pigmented patch or a raised ulcerated nodule, surrounded by pigmented mucosa, may be seen (Fig. 12.4). Prognosis is grave in nodular malignant melanoma.

Malignant lymphoma: Extranodal lymphoma arises principally in the oropharynx in the area of Waldeyer’s ring. Nodular infiltration of the mucosa is seen and lymph nodes in the neck may become involved.

Leukaemia: Leukaemia may present with oral signs such as persistent gingival haemorrhage and oral ulceration. Acute myeloid leukaemia and childhood leukaemia may cause gingival enlargement because of direct infiltration of leukaemic cells (Fig. 12.5).

Metastatic deposits: Metastasis from primary cancers in the kidney, gastrointestinal tract, lung, breast, prostate and other sites occur in the oral cavity. Often they present as gingival nodules or as destructive bone lesions. Metastatic lesions in bone are usually radiolucent, but prostate and some breast metastases appear as radio-opacities in bone.

Squamous-cell carcinoma

Smoking: Cigarette smoking is the most important aetiological factor for intraoral cancer in the Western world. Risk increases with cumulative dose, which is measured in ‘pack-years’. There are no safe levels. The risk is greatest when combined with high alcohol intake. It is believed that carcinogens in tobacco smoke accumulate in the floor of the mouth, accounting for the increased risk of squamous carcinoma at that site.

Paan and other tobacco use: Paan, also known as betel quid, is used throughout the Indian subcontinent. Leaf of the betel piper vine is used to form a rolled-up quid, into which areca nut is placed. Areca is thought to contain alkaloid carcinogenic precursors. In addition, tobacco, spices and slaked lime may be added. The quid is held in the oral cavity for a considerable time and is habit forming. Buccal and labial cancers are commonly associated with paan use. Other tobacco habits exist, including smearing tobacco paste into the mouth and reverse bidi smoking, which has been linked to palatal cancer. In recent times, areca nut has become popular in southeast Asia.

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses