12

Practice management tips

OVERVIEW

The provision of dental services and development of a treatment philosophy must integrate into a broader network of cross-disciplinary services for patients with developmental disabilities (PWDD). These networks are constantly undergoing changes based on funding availability, changing philosophies, training of providers, and other socio-economic factors. Changing budgetary constraints of state and federal reimbursement programs demand that institutional and community-based programs funded by the public sector must be run effectively and efficiently to service PWDD in difficult economic times. The private practitioner must be prepared to address the deficiencies in the fee compensation that exist relative to the time commitment that an office must make to service and treat PWDD.

Integration of mid-level providers is intended to enhance the availability of dental care for underserved patient groups and the income disadvantaged population. Development of new workforce strategies coupled with coordinated community dental health efforts may help address some of the dental health disparities faced by PWDD. This chapter will present practice management tips across the spectrum of treatment environments.

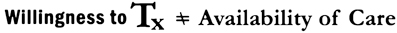

The dental profession has historically shown its willingness to provide dental care to PWDD. Each member of the dental team must be prepared to address the factors that create barriers to dental care for this population group. Unfortunately, the existence of these barriers means that, the willingness of providers to treat patients with developmental disabilities does not translate into the availability of care for this population (Figure 12.1).

Figure 12.1 The willingness of providers to treat does not equal the availability of dental care to persons with developmental disabilities.

PROVIDING TREATMENT AND MANAGING THE PRACTICE WITHIN THE DIFFERENT TREATMENT ENVIRONMENTS

Defining the treatment objectives often involves modification of your treatment approach. Beyond the clinician having an understanding of the oral conditions that are present in different diagnosis-specific disabilities (Tesini & Fenton 1994), he or she must understand the varied financial challenges that exist when providing care in different clinical environments. Individuals with developmental disabilities seek care based on (1) their residential environment, (2) the awareness of their health care needs, (3) the availability of the service within the community, (4) their diagnosis-specific disability and patient characteristics (i.e., medical history, behavior, disease prevalence, etc.), (5) the proximity of the service, and (6) the philosophical orientation of the caregiver (Tesini 1987).

Optimal qualities for an ideal system have been envisioned to include (Sheller 2007):

Practitioners and other programs have repeatedly noted problems in the provision of comprehensive dental care to individuals with disabilities (Tesini 1987; Edelstein 2007; Pradham et al. 2009; Rose et al. 2010). These include (1) limitations of the physical plant, (2) complications in time scheduling, (3) behavioral problems, (4) financial limitations for private practices to treat, (5) relatively few practitioners with adequate training, (6) capabilities of ancillary staff, and (7) guardianship and consent issues.

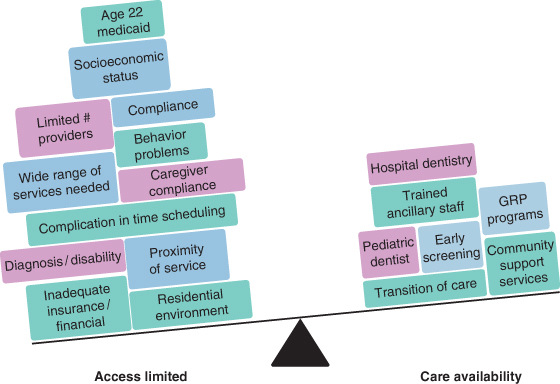

Figure 12.2 The fragility of the balance of access for patients with developmental disabilities.

The seesaw of access defines this balance between access availability and limited care availability and functions as a class I lever in physics (Figure 12.2). The effort (force) needed to overcome the weight of the distracters (i.e., barriers) to dental care for PWDD is not in balance.

While a broad overview of community-based interventions will be covered in Chapter 13, it is important to note these options in this chapter because part of managing a private practice includes understanding the services available in the community for patients with developmental disorders. The majority of patients with disabilities receive primary services treated in four major treatment environments:

Unique approaches must be found in order to overcome the barriers to care that exist for patients with developmental disabilities (Surgeon General 2000). Professional guidelines place PWDD in higher risk categories and recommend more frequent dental visits and preventive services (Crall 2007). This anticipates that the models of care and payment for care can accommodate more intensive services with greater frequency and starting at an earlier age (American Academy of Pediatric Dentistry 2010–2011).

Variation in dental care utilization within cohorts of PWDD is dependent on multiple factors including the financial burden, the source and utilization of medical care, race, insurance type, parents’ education, shortage of trained providers, and the severity of the disability (Iida 2010). The extent to which dental care utilization and expenditures in PWDD differ between groups of individuals with special health care needs and the general population may truly be determined by qualitative studies of parents and providers only (Beil et al. 2009). Surely it is dependent on the successful management of the practice environment.

The Association of State & Territorial Dental Directors (ASTDD) Best Practices Project defines “best practice” as a service, function, or process that has been fine-tuned, improved, and implemented to practice “superior results.” The ASTDD Best Practices Project presents state and community practice examples illustrating successful ways to implement approaches for addressing oral health issues of patients with special health care needs (Association of State & Territorial Dental Directors 2011a, 2011f).

Although the framework on which the program is based will vary depending on the population served and the program objectives, the approach to program development and management must address:

And we add:

The development of other initiatives such as a mutual access program or a community dental facilitator project can further allow integration of private practice and state-funded services. The mutual access model provides a “safety net” of primary generic care providers who support and rely on state-supported secondary and tertiary care that may not be available in a traditional private practice setting (Tesini 1987). Further, community facilitation at the local level can improve access to existing dental services by reducing barriers to dental care (Harrison et al. 2003).

The following care delivery models within selected treatment environments are not intended to be interpreted as exclusive to only one treatment environment. Programs, clinics, and private practices should consider aspects of multiple models from all treatment environments. This is how the practices serving PWDD need to be developed and managed in the future.

Federal- and/or state-funded dental facilities

Institutional-based programs can serve both residential and community-based clients. One example of this is the Tufts Dental Facilities for Patients with Special Needs (Association of State & Territorial Dental Directors 2011 g). These clinics, based at the institutions, were initially created to satisfy a legal mandate to provide care for residential clients. Later, with the realization that “institutions are in communities” (Special Care Dentistry Association 1998), community-residing clients were allowed access to comprehensive dental care. It was in this institutional dental clinic environment where most of the experienced providers were practicing (Southern Association of Institutional Dentists 2011).

The Tufts Dental Facilities model has four interwoven components:

As these types of programs develop, most of the clinical care for both institutionalized and non-institutionalized (or deinstitutionalized) people can be provided in more traditional community office settings. Other approaches that integrate well into this model have also been described:

- North Carolina institution-based—two institution-based dental clinics in North Carolina serve persons with disabilities who live in the community. Both programs have a common objective of providing access to dental care for persons with disabilities who live outside the institution and are unable to obtain care from community sources (Association of State & Territorial Dental Directors 2011b).

- Butler County—the Butler County Dental Care Program is a dental case management program sponsored by the Butler County Board of Mental Retardation and Developmental Disabilities in the state of Ohio. The program does not pay for dental services but rather integrates networks of providers, hospitals, professional organizations, case managers, caregivers, and guardian agencies. It combines existing resources to provide appropriate dental care in a timely manner to people with special needs (Association of State & Territorial Dental Directors 2011c).

- Operating Room Dental Practice—this hospital-based dental practice provides access to care for patients with special needs who require general anesthesia to obtain their treatment due to behavioral problems (Association of State & Territorial Dental Directors 2011d).

- A mutual access program, as previously discussed, is designed to support any generic system of oral care delivery.

All programs, institutional or community-based, must be driven to an efficiency level well beyond state and federal mandates to ensure long-term success and sustainability. Additional details on this topic can be found in Chapter 13.

Private practice models

Private practices have not seen a financing system that has been responsive to the dental needs of persons with developmental disabilities. Private practice settings require a disciplined approach to managing dental care delivery that can integrate PWDD into the solo or group practice dynamic. From office design (new or renovated) to efficient scheduling, every detail should be carefully reviewed for treatment success. Some private practices, whether general or specialty limited, develop a special care “niche,”and these referral sources should be fostered. Parents and caregivers should understand that these referrals are being made to improve care delivery.

One such private dental office is in California. A pediatric dentistry practice developed an approach that focuses directly on social and behavioral challenges specific to autism. The design of the office includes an acoustically isolated dental operatory and playroom. The “Poppy Room,”as it is called, is equipped with multisensory devices such as bubble tubes, image projectors, weighted blankets, and video glasses (Brennan 2011). Specific scheduling for this room is done with the busy pediatric dentistry environment of a private practice. Modifying the treatment environment may further enhance advanced behavior management techniques such as applied behavior analysis (Hernandez & Ikkanda 2011) and the D-Termined™ Program of Familiarization and Repetitive Tasking (Tesini 2010).

Hospital-based dental clinics

Hospital-based dental services exist primarily to meet the needs of the low-income, uninsured, and other special patient populations. They are often university affiliated and serve as a community safety net, especially in providing emergency services. They can also function as general practice residency program centers.

All hospital departments are just that—a hospital department. It must function within and be part of the highly regulated hospital environment. Successful management is based on (National Maternal and Child Oral Health Resources Center 2005):

Mobile dental clinics

The availability of comprehensive dental care to PWDD is probably most problematic in the rural environment and for those individuals unable to leave their living environment (Skinner et al. 2006). These dental delivery models may be based through either mobile vans or through “in-home dental teams.” Mobile vans can allow for state-of-the-art equipment to your door. House calls define the latter, where “in-home dental teams” are more of a house-call model where basic dentistry is provided in the living environment and often even in the patient’s bed. One such program, whose motto is “We make smiles happen at home,” coordinates dental house calls by dentists and auxiliaries for homebound individuals (Portable Dental Services 2011).

The Truman Medical Center in conjunction with the Missouri Department of Health provides one of the best examples of accessible free dental services utilizing a 33-foot mobile dental van. Children and adults with developmental or intellectual disabilities in extreme financial distress, and who have found it impossible to receive care anywhere else, are eligible through referral by a local Elk’s lodge (Truman Medical Center 2011).

In addition to the practice models presented, a “bridge” for compliance must be established. Partnerships with ever-changing community residential m/>

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses