5

Overall health

OVERVIEW

In treating patients with developmental disorders, dental practitioners find themselves facing unique challenges that are not common in other patient populations. Because patients with developmental disorders are more reliant upon the system of care that surrounds them, they suffer greater health consequences when that system of care breaks down. In order to decrease the likelihood of health system failure, health professionals from all disciplines need a more holistic view of the patient and of patient care. This can be achieved through greater interdisciplinary understanding and communication. Dentists who have a greater neurobiological understanding of the whole patient will be more effective members and leaders of the health care team upon which their patients rely.

TERMINOLOGY

For clinicians first beginning to work with this patient population, one of the most immediate challenges is understanding the terminology used in different professional, advocacy, and legal circles that refers, often imprecisely, to the same (or nearly the same) population.

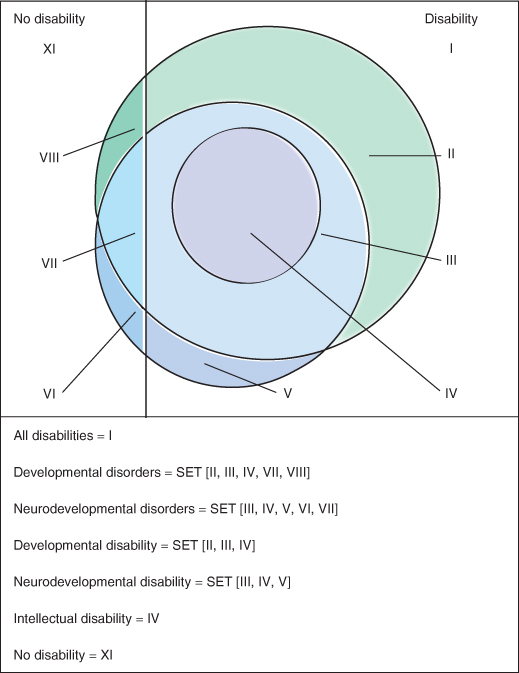

Figure 5.1 Venn diagram showing the relationship between different terms used to describe this patient population.

Two terms that should not be used when describing this population are “mental retardation” and “cognitive impairment.” “Mental retardation” is an outdated term that is increasingly being viewed as offensive to people within the disability community. The term “mental retardation” has been effectively replaced with the synonymous term “intellectual disability” (ID) (Schalock et al. 2007).

“Cognitive impairment” is often mistakenly used as a synonym for “intellectual disability.” Though functionally the adult patient with cognitive impairment and the adult patient with ID may be indistinguishable, cognitive impairment is a much more broad term that can refer to both temporary and permanent intellectual states and may include an onset of symptoms during either childhood or adulthood. As an example, cognitive impairment could refer to a temporary state of drug-induced delirium in a 70-year-old patient or a permanent state of ID caused by trisomy 21.

In the United States, there are five widely used terms that often refer to the same population: “intellectual disability,” “neurodevelopmental disability,” “neurodevelopmental disorder,” “developmental disability,” and “developmental disorder.” Though there is significant overlap among these five terms, it is important to appreciate the relationships and the differences among them. Figure 5.1 shows the relationships among these terms. In order to better understand this, consider that the entire population is divided into two segments, those who are disabled and those who are not disabled. Though what factors determine “disability” can often be vague, for purposes of this illustration consider that there are two groups of people and that the difference between these two groups is easily demarcated by a line.

The most broad term is “developmental disorder.” A natural subset of people with developmental disorders are those whose disorders have led to a disability, thus they are people with a developmental disability. Closely overlapping the set of people with developmental disorders is the set of people with neurodevelopmental disorders. The reason that the latter is not a perfect subset of the former has to do with the underlying vocational fields that define the terms. “Developmental disability” and thus “developmental disorder,” by extension, are often sociologically or legally defined terms, whereas “neurodevelopmental disorder” and thus “neurodevelopmental disability,” by extension, are biologically defined terms. A natural subset of neurodevelopemental disorder is neurodevelopmental disability, that is, neurodevelopmental disorders that have resulted in disability. Finally, found within all of the previous sets mentioned is the set of people with ID.

Intellectual disability

Intellectual disability is characterized by significant limitations in both intellectual functioning and adaptive behavior as expressed in conceptual, social, and practical skills. This disability originates before age 18 (Schalock et al. 2010). It is a common symptom of multiple developmental and neurodevelopmental disorders.

Neurodevelopmental disability

Neurodevelopmental disabilities are disabilities that can be attributed to neurodevelopmental disorders. Some neurodevelopmental disabilities are well defined and others are not. Intellectual disability is one type of neurodevelopmental disability. Autism (that is severe enough to be recognized as a disability) could be construed as a neurodevelopmental disability. Cerebral palsy in many cases could be considered a neurodevelopmental disability as well. Neurodevelopmental disability overlaps considerably, by definition, with developmental disability.

Neurodevelopmental disorder

A neurodevelopmental disorder is a genetic or acquired biological process, occurring before adulthood, that disrupts one or more of the expected functions of the brain, resulting in one or more common complications. Such complications include: (1) intellectual disability, (2) neuromotor dysfunction, (3) sensory impairment, (4) seizure disorder, and (5) abnormal behavior. Neurodevelopmental disorders, depending upon their etiology, can be associated with various syndrome-specific conditions. Both the common complications and syndrome-specific conditions can, and often do, lead to secondary health consequences. These characteristics of neurodevelopmental disorders will be discussed further in this chapter (Rader 2007).

Developmental disability

Developmental disability is a socio-legal construct. Because its definitional roots are not biologically based, the definition can vary from state to state. Under most circumstances, neurodevelopmental disability would be considered a subset of developmental disability; however, because both definitions can be ambiguous as to the age at onset of symptoms, it is possible for some patients to be considered to have a neurodevelopmental disability while not having a developmental disability. Though the definition of developmental disability can vary, a typical definition would include but is not limited to people who have an ID, autism, cerebral palsy, a severe seizure disorder, or a severe head injury that occurs before the age of 18.

Under federal law, developmental disability means a severe, chronic disability of an individual that (1) is attributable to a mental or physical impairment or combination of mental and physical impairments; (2) is manifested before the age of 22; (3) is likely to continue indefinitely; (4) results in substantial functional limitations in three or more of the following areas of major life activity: self-care, receptive and expressive language, learning, mobility, self-direction, capacity for independent living, economic self-sufficiency; and (5) reflects the individual’s need for services, supports, or other forms of assistance that are of lifelong or extended duration and are individually planned and coordinated (Developmental Disabilities Assistance and Bill of Rights Act of 2000).

Developmental disorder

A developmental disorder is the biological cause of the underlying developmental disability. Most neurodevelopmental disorders, such as Down syndrome, fragile X syndrome, and fetal alcohol syndrome, are also considered developmental disorders. Developmental disorders may also encompass other disorders of nonneurologic origin such as muscular dystrophy.

COMMON CHARACTERISTICS

In general, regardless of the terminology used to describe this patient population, there are common biological characteristics that will affect patient care. Though people with purely physical disabilities may require special accommodations, it is the patients with neurodevelopmental disorders that tend to present the greatest challenge for the dental practitioner. Understanding the characteristics of these patients and appropriately adjusting the clinical approach to the patient based on these common characteristics will ensure the greatest chance of clinical success.

Etiology

No matter how the patient presents, it is important to remember that all disabilities have a cause. Very often patients will arrive at the clinic with the “diagnosis” of intellectual disability, with no other explanation. As clinicians it is important to attempt to ascertain the underlying cause of the ID. There are potentially thousands of causes of intellectual disability that exist. Though many causes are still unknown, as the state of science has evolved, more and more causes of ID are being described. Determining etiology is important because etiology can affect prognosis and determine specific preventive health measures that can be taken. Intellectual disability caused by Down syndrome, for example, leads the clinician to a much different clinical picture than ID due to lead toxicity. Knowing the etiology can greatly affect preventive health measures and, just as importantly, can be very powerful information for family members. Such information will not only guide the care of the patient; if it is an inherited disorder it may also have a significant effect on future family planning (Box 5.1).

In order to help discover etiologies, dentists should familiarize themselves with some of the more common morphologic features of the head and neck of the more recognizable syndromes. Though Down syndrome can be recognized by most clinicians, many other syndromes such as fragile X, Prader-Willi, Angelman, Williams, fetal alcohol, Cornelia de Lange, Turner, and Sturge-Weber have distinctive physical features that can be recognized by the dentist. If a dentist suspects that a patient may have a previously undiagnosed syndrome, he or she should not hesitate to refer the patient to a geneticist for further evaluation. Because of the rapidly advancing field of genetics, even if the patient had a negative genetic evaluation in the past, if that evaluation is more than 10 years old, the patient may benefit from another evaluation.

Etiology can be divided into two broad categories: genetic and acquired. Genetic causes are present at conception; acquired causes may be prenatal, perinatal, or postnatal in nature. In general, the closer in time an etiology is to conception, the more likely it is that it will affect more organ systems of the developing person and that those effects will produce a physically recognizable syndrome. Practically, this means that if an etiology has not yet been determined for an individual, a person who appears to have more body systems affected by the disorder is more likely to have an underlying genetic cause rather than an acquired cause.

Common complications

Neurodevelopmental disorders tend to produce one or more of five general categories of common complications. These common complications include (1) intellectual disability; (2) neuromotor dysfunction; (3) seizure disorder; (4) psychiatric disorders; and (5) sensory impairment.

Though no estimates exist regarding the percentage of people with neurodevelopmental disorders having any of these particular complications, in the presence of ID, the likelihood of any one of the other four complications also being present is around 25% (Holder et al. 2007) (see Table 5.1).

Table 5.1 Complications of neurodevelopmental disorders associated with ID.

| Neuromotor dysfunction: 20–30% Seizure disorder: 15–30% |

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses