CHAPTER 12 PLANNING FOR COMMUNITY DENTAL PROGRAMS

Microbiologist Rene Dubos has suggested that most of human history has been a result of accidents and blind choices.1 When a crisis occurs, our solutions are immediate and involve piecemeal efforts rather than considered and thoughtful planning. The need to develop our ability to predict, plan, and thus prevent the same crisis from recurring should have the highest priority.

WHY PLAN?

Planning Dental Care for the Patient

The steps the dentist takes when seeing a patient for the first time can be compared with the steps a planner takes when viewing a system for the first time. A new patient who walks into the dental office is given a medical and dental history form to complete. This record provides background information on the patient’s health, history of diseases, and drug reactions, as well as the patient’s history of dental care. Information on the patient’s ethnic background, degree of education, and financial status may indicate the patient’s attitude about dental care, the type of dental care wanted, and how that care will be financed. A clinical examination with the use of radiographs further reveals the type and quality of dental care received and identifies any existing conditions or disease requiring treatment. For the dentist these steps assess the needs of the patient.

When treatment has been completed, the patient is placed on an appropriate recall schedule and returns to have an evaluation of the care that was rendered. Any modifications or adjustments are done at this time. The patient is then placed on a maintenance plan and returns periodically for a routine examination. This becomes an ongoing process for the patient and the dentist. The difference between the planning steps for an individual patient and the planning steps for a community is that dealing with more than one individual at a time requires more complex steps. Box 12-1 compares the provision of dental care for a private patient with that for a community.

BOX 12-1 A Comparison of the Provision of Dental Care for a Private Patient and a Community

Modified from Young W, Striffier D: The dentist, his practice, and the community, Philadelphia, 1969, WB Saunders.

Private Patient

Community

Planning Dental Care for the Community

Usually a planner is contacted because a problem has been identified within the community, for example, a high incidence of early childhood caries (ECC) among children. The planner, like the dentist, begins by conducting a needs assessment of the affected children and their families. Included in the needs assessment are the population’s health problems and beliefs, ethnic makeup, diet, education and socioeconomic status, number of children with ECC, and the severity of the disease.2 Again, this information will help the planner in determining an appropriate plan.

After the children have been treated, a 6-month follow-up examination is instituted to evaluate the effectiveness of the plan. At that time the planner addresses questions such as the following: How many children identified as having ECC were treated? How many dropped out of treatment, and why? How many developed new ECC? The answers to these questions will help the planner to modify and adjust the program according to the needs of the community.3

Many kinds of planners exist. Some have been professionally trained or educated, whereas others have received on-the-job experience within their organization. There are two distinct approaches to planning: internal, planning by individuals within the system or organization; and external, planning by those brought in from outside.4 A planner hired from within the system is usually an individual whose work responsibility is to plan for the system on a full-time basis. The advantage of hiring from within is that the planner already has a true understanding of the issues and operation of the system, including the subtleties of that system. This knowledge enables the planner to begin making decisions more quickly regarding appropriate action. The disadvantage, however, is that the planner may already have acquired certain biases about the system that could influence his or her objectivity.

One of the most important concerns for any planner is to take into consideration the human element. Statistics alone do not tell the whole story. For example, a planner who reviews the health labor statistics on a multiethnic community and who sees that, overall, sufficient numbers of practitioners work within the community may think that the community does not need any new practitioners. A closer examination of the practitioner and patient populations may reveal that the practitioners are primarily of a certain ethnic background and do not like treating patients of different ethnic backgrounds, of which there are a great number in the community. Thus large subgroups of the population may not have access to dental care, even though statistically enough dentists are available in the community.5 Although statistics can be most useful in analyzing data, a planner must be aware of their limitations.

PLANNING: A DEFINITION

Banfield presents a basic definition of the term planning: “A plan is a decision about a course of action.”6 In other words, a plan is a systematic approach to defining the problem, setting priorities, developing specific goals and objectives, and determining alternative strategies and a method of implementation.

Many types of health planning exist. Each varies according to the factors affecting the health system, such as the geography of a region, the sociocultural background of the population, economic considerations, and the political situation. Some types of health planning, as outlined by Spiegel and associates,7 include the following:

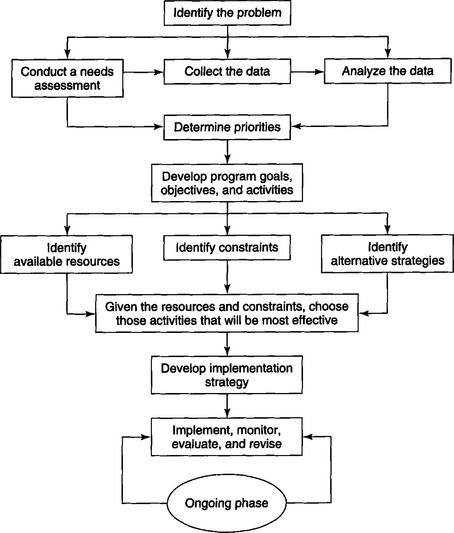

This chapter describes various types of health planning but concentrates specifically on the program-planning process. This process of program planning uses a systematic approach, as seen in Fig. 12-1, and should be used as a guide to solving a particular problem. The process can be compared with the ability of a jazz musician to take the notes of a standard musical scale and use them to create a unique melody. In a similar fashion, a planner uses the program-planning steps to create a plan that is unique for the specific situation or system. The process of planning is dynamic. Within a fluctuating and ever-changing system, the process itself must remain fluid and flexible, responsive to the presentation of new factors and issues. This chapter discusses the components of program planning and focuses on the various options available to the planner. The initial step in the planning process is to conduct a needs assessment.

There are several reasons why a planner should conduct a needs assessment. The primary reason is to define the problem and to identify its extent and severity. Second, the assessment is used to obtain a profile of the community to ascertain the causes of the problem. This information helps in developing the appropriate goals and objectives in the problem solution. Assessing the community’s needs not only involves identifying existing health problems but also potential health problems and health promotion needs.8

Suppose the planner designed a program to administer fluoride tablets to all school-age children in a given community. To determine how effective a fluoride tablet program is in terms of reduction of dental caries, the planner would first establish a baseline needs assessment of the caries rate among the school children. After the initial assessment, the program is implemented. To measure the effectiveness of such a preventive regimen, the planner would then make periodic assessments of the schoolchildren at various time intervals and compare these results with the initial assessment.

Another method is to investigate surveys that have been done in the past by other organizations. Frequently, dental surveys are conducted through research departments of dental schools or through local and state health departments. If no surveys have ever been done, the planner may either want to solicit the assistance of these agencies and organizations or inform them that a survey will be conducted. This approach prevents overlap or duplication of activities.

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses