11

11

Secondary Cleft Lip and Palate Deformities

Introduction

Cleft lip and palate deformities are the most common congenital deformities of the facial region. This chapter will focus on the secondary correction of cleft-related deformity.

The management of secondary deformity must involve the surgeon, orthodontist and speech pathologist working closely with the paediatrician, ear nose and throat surgeon, plastic surgeon, and clinical psychologist when appropriate.

The clinical problem depends on the type and severity of the cleft and on the type, extent and quality of the primary surgery and any revisions of these “primary procedures”. Compromises between function, aesthetics and growth have to be made which determine the timing of surgery. For instance the timing of palate repair is a balance between enabling speech development and optimum facial growth. What ever the compromise the number of operations must be kept to the minimum.

Important Factors

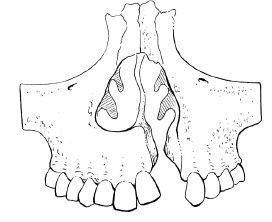

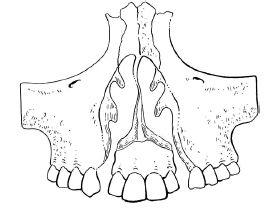

1. The amount of tissue in the original embryological defect (Figure 11.1).

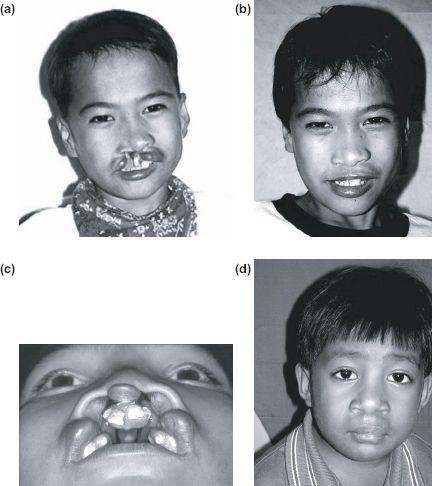

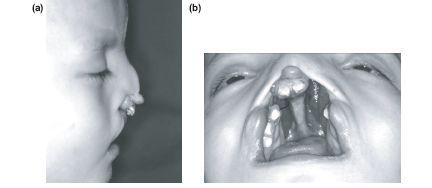

Although structures may be displaced, the amount of soft tissue is not usually deficient in the unrepaired unilateral or bilateral cleft deformity (Figures 11.2a–11.2d). Impaired growth and development usually arise from subsequent surgery rather than inherent differences in growth potential. The exception is in some bilateral cases where the premaxilla and pro-labial segment can be relatively small before surgical intervention (Figures 11.3a and 11.3b). True aplasia of tissue is uncommon although can be seen in cases of mid line clefting.

Figure 11.1 A complete cleft of the lip and palate extends through the alveolus in the region of the left lateral incisor with or without fistula extending into the nose.

2. The nature and quality of the primary surgery.

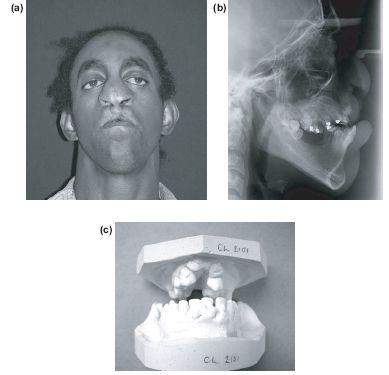

Facial deformity will develop as a consequence of scar contraction following surgery especially in the palate (Figures 11.4a–11.4c).

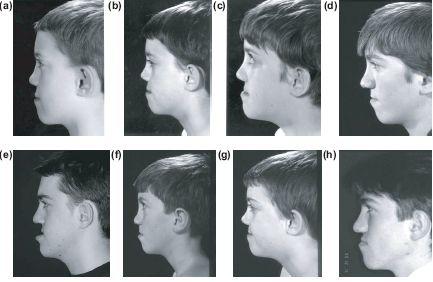

Patients with similar clefts repaired in different ways may exhibit different patterns of facial growth. Figures 11.5a–11.5h illustrate two brothers, both with complete right side unilateral cleft lip and palate operated using different palatal techniques demonstrating different mid facial growth.

3. Also important is the preservation of tissue. Tissue removal should be avoided whenever possible.

Figure 11.2 Soft tissues are not normally absent in the typical untreated unilateral or bilateral cleft (a), (c) preoperatively, and (b), (d) postoperatively.

The surgical correction of skeletal cleft deformity presents a greater challenge than most orthognathic procedures. A variety of programmes for treating these cases is possible. Unfortunately the selection of operation is usually dictated by the surgeon’s preference rather than objectively compared data.

Figure 11.3 Hypoplasia may occur in bilateral cases — particularly of the premaxilla and prolabial segments.

Figure 11.4 Surgery, particularly to the palate can cause secondary changes resulting in marked deformity of the mid-face.

Figure 11.5 Surgically impaired growth potential can be impossible to predict as illustrated by these two brothers.

Surgical Instrumentation

Intra-oral access is possible with a Mushin dental prop but this can be distracting at crucial moments. A self-retaining gag such as a Featherstone is better, but for ultimate ease one should use a cleft palate gag such as the Kilner modification of the Dott or the Dingman, which also provides simultaneous retraction.

The choice of needles is crucial, and include the 5/8 25 mm (Denys Browne), a 16 mm slim blade needle or the small J shaped compound curved needle mounted with 4/0 or 5/0 Vicryl Rapide (Ethicon). Children do not like suture removal. Small needles demand a fine-tipped ratchet needle holder, e.g. Stille Converse, and very fine dissecting forceps, e.g. Adsons. Subperiosteal flap dissection within a cleft also requires a small sharp periosteal elevator such as the McDonald, Friers pattern or even a Mitchell’s trimmer.

Table 11.1 Pathway of care

Early stages of treatment

Aims:

- Reconstruction of the oral sphincter and restoration of an acceptable appearance.

- Reconstruction of the soft palate to allow speech development.

- Avoid unnecessary surgery and enable optimal facial growth.

- Normal psychosocial development.

Means:

- Lip repair within first 6 months.

- Soft palate repair at one year of age.

- Speech therapy.

- Secondary hard palate surgery should be delayed as long as possible. Usually until 12 months.

Treatment in the mixed dentition

Aims:

- Orthodontic alignment of the developing dentition.

- Reconstruction of the alveolar cleft and dental arch form.

- Oronasal fistula closure.

- Restore normal symmetrical maxillary bony contour.

- Stabilisation of the dentoalveolar segments.

- Maintenance of a healthy adult dentition.

Means:

- Orthodontics essential for surgery.

- Alveolar reconstruction with bone grafting.

- Segmental alveolar distraction osteogenesis where appropriate.

- Fistula closure.

- Preventative and restorative dental care.

Treatment in adolescence and early adulthood

Aims:

- Correction of any disturbance of facial growth and skeletal imbalance.

- Reconstruction of nasal deformity.

- Correction of any soft tissue deformity.

- Correction of any occlusal disturbances.

- Provision of an aesthetically pleasing smile.

Means:

- Presurgical orthodontic treatment.

- Malar maxillary distraction osteogenesis where appropriate.

- Orthognathic surgery to correct secondary skeletal deformities.

- Post-orthognathic orthodontics.

- Residual fistula closure.

- Dental reconstruction.

- Definitive nose and lip correction.

The Surgical Procedures

Establishment of bony continuity (bone grafting of the alveolar cleft).

- The optimum time for alveolar bone grafting is between 7 and 12 years, before the permanent canine on the cleft side erupts and when half to two thirds of its root has formed.

- At this age, anteroposterior and transverse maxillary growth is practically complete apart from the alveolar development of the erupting permanent teeth. Hence grafting at this time does not affect mid face growth but provides the all important bone support for the erupting canine.

- The bone also enables orthodontic positioning of the canine.

- Creates a one piece maxilla for orthognathic surgery.

- Provides stabilisation for any prosthetic replacement.

- It is also possible to simultaneously graft the alar base.

Prior to grafting, presurgical orthodontics will have expanded the maxillary arch to restore the arch form between the major and lesser segments. The teeth adjacent to the cleft will have been aligned providing there is sufficient bone around the roots and a good periodontal attachment to accommodate the alignment.

If the premaxillary segment has been surgically repositioned forwards or orthodontic arch expansion has been used to facilitate the grafting procedure, a retaining appliance is essential to prevent collapse before consolidation of the bone graft.

The Problems

- A unilateral alveolar defect.

- Anterior oronasal fistula.

- Alar-base asymmetry.

Surgical Treatment

1. Instruments should comprise a basic intraoral surgical set with the addition of a fine periosteal elevator, such as a McDonald, Frier or Mitchell’s trimmer, and skin hooks. Access may be gained with a Dingman cleft palate or Featherstone gag.

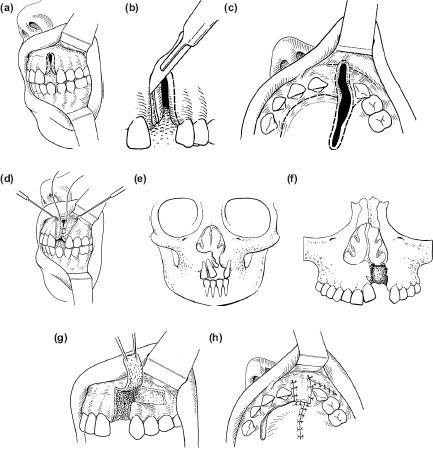

2. The incision is made down to bone around the margin of the anterior fistula, except where the fistula lies high in the anterior vestibule beneath the upper lip. At this point there is no underlying bone and the incision is through mucosa only (Figures 11.6a–11.6d).

Figure 11.6b shows how the narrow strip at the cervical margin of the tooth is sliced to create as wide a band of de-epithelialised tissue as possible.

The initial incision can be extended safely along the buccal sulcus overlying the lesser segment unless a segmental osteotomy is required.

If the fistula or alveolar defect extends into the palate a palatal flap will need to be raised (Figure 11.6c).

Subperiosteal dissection is directed into the fistula and the liberated soft tissues are pushed up towards the nasal cavity.

Much of this tissue becomes redundant and can be cut away leaving just sufficient to form a nasal layer.

Figures 11.6 Alveolar bone grafting with simultaneous repair of oral and nasal mucosal layers. The rotator finger flap (g and h) is seldom used in current practice.

3. Where the soft tissues bridge the cleft, i.e. in the buccal sulcus and behind on the palate, two layers are created by sharp dissection.

4. If the fistula is wide enough the nasal layer can be closed with resorbable sutures on a very small needle (Figure 11.6d). If the bone defect is too narrow to insert a suture in the nasal layer (Figure 11.6e), a piece of oxidised cellulose (Surgicel, Ethicon Ltd, Edinburgh, UK) or acellular submucosal matrix can be inserted to seal the nasal surface of the cleft (Figure 11.6f). Any supernumerary teeth are extracted and cancellous bone chips are packed into the whole defect.

5. Cancellous bone chips are obtained from the iliac crest and packed firmly into the bone cleft. A substantial amount may be required as it is particularly important to pack bone up under the lateral part of the alar cartilage to create a nasal sill (Figure 11.6g).

6. An oral defect remains at the site of the original incision. These margins cannot be brought together as they are largely attached gingiva.

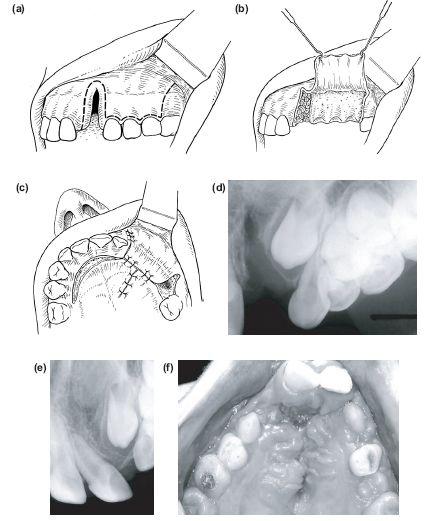

7. A mucogingival transposition flap pedicled superiorly in the sulcus is raised and mobilised by dividing the inelastic periosteum with a sharp blade. When rotated into position it leaves a bare area of buccal alveolus distally, which will epithelialise spontaneously. This technique is most useful after bone grafting in the patient with a mixed dentition. In these cases the oral defect is narrow and the transposition flap is taken from the gingival margins of the deciduous molars, which are usually extracted at the same time (Figures 11.7a–11.7c).

8. The flap is rotated over the bone graft and sutured to the margins of the fistula with 5/0 Vicryl on a 16 mm slim blade needle. This must be done meticulously with multiple fine sutures to produce a watertight edge-to-edge closure (Figure 11.6h).

Figure 11.7 (c) Raising and rotating a buccal transposition flat. (d) Ungrafted cleft. (e and f) Canine erupting through consolidated bone graft.

9. The palatal flap from the greater segment is not always required in small defects.

10. Figures 11.7d–11.7f show the alveolar defect before and after grafting and the erupting canine.

Postoperatively

Intraoral bone grafts in cleft patients require meticulous postoperative care. The following precautions are recommended:

- Preoperative intravenous antibiotics should be administered and then postoperative prophylactic antibiotics given orally for 5 days.

- Maintain scrupulous oral hygiene. The patient is given a semi- solid diet by mouth and chlorhexidine gluconate mouthwashes.

- Adequate analgesia for both oral and donor sites.

Segmental Surgery

Segmental surgery is now rarely required at the time of alveolar bone grafting, as orthodontic preparation or distraction osteogenesis will usually align the segments. It should be avoided because

a) fixation is problematic and

b) bone grafts do not unite with mobile segments.

However, the local dentoalveolar relationship may be improved by combining the alveolar bone graft with an osteotomy to the lesser segment or premaxilla. The most common indications are:

- Adequate vertical and anterior growth of the greater alveolar segment but vertical deficiency of the lesser segment. This may be associated with dental arch collapse and recession with asymmetry of the nasal base.

- The fistula is too large to close for bone grafting, and soft tissue coverage is not possible.

- Orthodontic expansion of the arch has not been possible as the lesser segment may be trapped palatally.

- Distraction osteogenesis is not available.

The Problems

- A unilateral alveolar defect.

- Anterior fistula and nasal base asymmetry.

- Deficient vertical growth of the lesser segment and collapse of the maxillary dental arch.

The Surgical Treatment

- Osteotomy to reposition the lesser segment.

- Bone graft to the alveolar defect and osteotomy site.

- Closure of the anterior oronasal fistula.

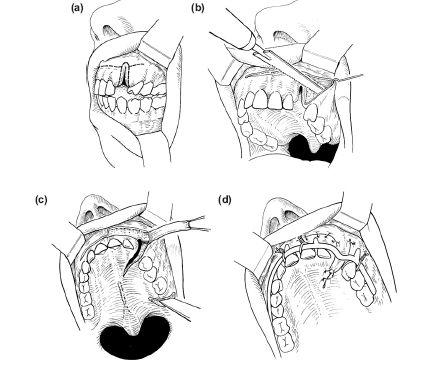

- The initial incision is made around the intraoral margin of the fistula, as before. A horizontal sulcus incision can be made at this stage to improve access but this incision should now be made along the line of the greater segment (Figure 11.8a).

- The lesser segment osteotomy is carried out at the LeFort I level from the buccal side by inserting a suitably protected bur or the narrow blade of a reciprocating power saw. The horizontal cut is carried through until the blade action can be palpated beneath the attached palatal mucosa (Figure 11.8b).

- The lesser segment is still not free posteriorly. In cleft patients the anatomy of the tuberosity-pterygoid plate junction is frequently distorted and the bone may be very dense in this area. In order to free the segment, a 1 cm mucosal incision is made behind the tuberosity and a 7 or 10 mm thin osteotome directed vertically (Figure 11.8c).

Figure 11.8 Lesser segment of alveolar osteotomy at the time of alveolar bone grafting.

4. The freed lesser segment is now further mobilised by blunt dissection until it can be aligned according to the preoperative plan.

5. If the dental arch is expanded to any extent it will open up the cleft of the hard palate. This can only be made good by lifting and rotating the mucoperiosteum covering the palatal aspect of the greater segment and suturing it to the freshened edge of the palatal mucosa covering the lesser segment. The palatal mucosa covering the lesser segment should remain attached to maximise the blood supply to the segment. In practice, nasal layer closure is not found to be a problem, even after surgical expansion of the maxillary arch.

6. Cancellous bone chips and sheets of cancellous bone obtained from the iliac crest or by trephining the tibia, are used to fill the alveolar defect and to pack the osteotomy site on the lesser segment.

7. The lesser osteotomised segment is immobilised by attachment to the greater segment using a preformed arch bar (Figure 11.8d) ligated with 0.35 mm prestretched soft stainless steel wire.

8. There remains the oral mucosal defect on the buccal and alveolar aspect of the cleft. It is not advisable to raise an anteriorly based finger flap or buccal mucogingival transposition flap if above changes are made as suggested, this should be removed because this would compromise the buccal mucosal attachment to the osteotomised segment. The vestibular finger flap is therefore based posteriorly and raised from the mucosa and submu- cosa of the buccal sulcus between the anterior part of the greater segment and the lip, as shown in Figures 11.8c and 11.8d.

9. Suturing and postoperative care are as already described above.

Bilateral Clefts (Figure 11.9)

Orthognathic surgery for bilateral clefts is very difficult and should only be attempted by experienced surgeons. Three presentations will be considered. However all cases are complicated by:

i) scarring of the prolabium indicating poor vascularity,

ii) multiple previous operations,

iii) a large anterior palatal fistulae extending bilaterally through the alveolus, and

iv) marked asymmetry.

Presentation 1 — The Problems

- Large anterior palatal fistulae extending bilaterally through the alveolus.

Figure 11.9 Care must be taken not to compromise the blood supply of the premaxillary segment in bilateral cleft cases.

- Recession of the nasal tip.

- Shortening of the columella.

- Symmetrical flaring of the alar bases.

The Surgical Treatment

Closure of the anterior fistulae with bone grafts to the alveolar defects.

- Reconstruction of the nasal sills providing bony support to the alar bases.

- Lengthening of the columella, and forward repositioning of the alar cartilages with narrowing of the nasal tip.

- Rotation of the alar bases inwards towards the mid line.

- Narrowing of the nasal bridge (see Rhinoplasty).

- Orthodontic expansion of the maxillary arch must precede surgery. Rapid maxillary expansion may be employed if the scarred palatal tissues are later mobilised surgically.

- If the maxillary arch alignment and forward development is adequate, surgical dissection of the anterior fistulae and alveolar defects can proceed as in the unilateral case, duplicating the surgery for each of the two clefts (see previously).

- Teeth in the premaxillary segment adjacent to the cleft alveolus on each side may be found to be denuded of bone. This applies particularly to any remaining lateral incisors. In order to achieve a successful bone graft such teeth must be removed.

- It is difficult to raise a healthy mucoperiosteal fl/>

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses