Psychologic State and Pain Perception

Petra Schweinhardt

Marco L. Loggia

Chantal Villemure

M. Catherine Bushnell

Why do some people experience terrible pain during a dental procedure, whereas others experience little or no pain during the same procedure? Are some patients just less tolerant than others, or does the pain experience actually differ from person to person? For many reasons, including individual genetic makeup and life experiences, not everyone experiences a painful stimulus in the same way. Evidence now shows that the varied perceptual experiences of pain are based on different levels of activity in pain-transmission and pain-modulation pathways in the brain. This chapter will address how the psychologic states of people can affect the processing of nociceptive information in the brain and, therefore, their perceptions of pain.

There have always been anecdotal accounts of people apparently experiencing little or no pain in situations that most of us would find intolerable, yet Western medicine has given little credence to a patient’s ability to modify pain, focusing instead on the pharmacologic control of pain. For this reason, the majority of research on pain control has concentrated on peripheral and spinal cord mechanisms of opioid and anti-inflammatory analgesic therapy. Nevertheless, researchers are increasingly recognizing that a variety of pain-modulation mechanisms exist within the nervous system and that these can be accessed either pharmacologically or through contextual and/or psychologic manipulation.1 Variables such as attentional state, emotional context, empathy, hypnotic suggestions, attitudes, and expectations, including the placebo response, now have been shown to alter both pain processing in the brain and pain perception. Techniques that modify these variables can preferentially alter sensory and/or affective aspects of pain perception. The associated modulation of pain-evoked neural activity occurs in limbic and/or sensory brain regions, suggesting multiple endogenous pain-modulation systems (see chapter 8).

Focusing on Pain Can Make It Worse

Attentional state is probably the most widely studied psychologic variable that modifies the pain experience. A number of clinical and experimental studies show that pain is perceived as less intense when a person is distracted from the pain (see Villemure and Bushnell2 and Apkarian et al3 for a review). Distraction was achieved in these studies by asking subjects to focus on something else. In a clinical setting, patients may be given music to listen to or videos to watch. However, a few studies indicate that focusing on pain may actually have the paradoxic effect of reducing its perceived intensity in certain individuals. For example, Hadjistavropoulos et al4 observed that chronic pain patients who were particularly health anxious reported less anxiety and pain when they focused on the physical sensations. Thus, the effect of attention and/or distraction on pain may not be uniformly predictable but rather influenced by such variables as personality type.

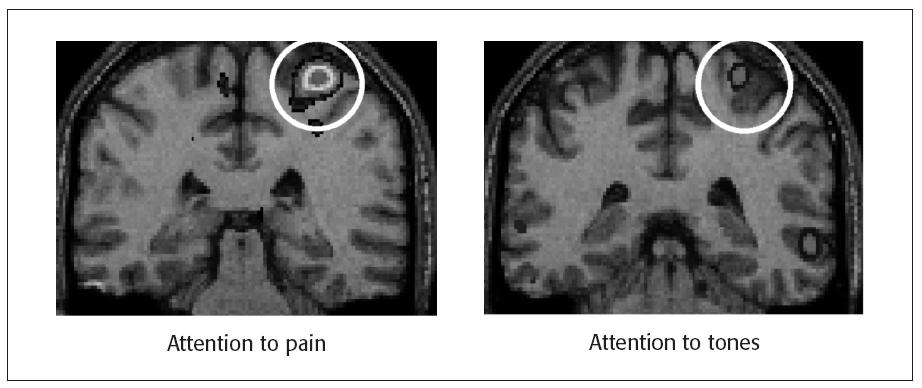

In some studies, subjects were asked to rate separately how intense the pain sensation was and how much it bothered them (ie, pain intensity versus pain unpleasantness). These studies have shown that attending to another sensory modality during pain results in parallel reductions in both perceived intensity and unpleasantness of the pain, sometimes with a greater modulation of pain intensity.5 Correspondingly, attention-related modulation of neural activity evoked by noxious stimuli has been observed in pain-related pathways throughout the brain. At the level of the cerebral cortex, imaging studies have shown attention-related modulation of pain-evoked responses in both sensory and limbic cortical areas, including the primary (SI) and secondary (SII) somatosensory cortices, the anterior cingulate cortex, and the insular cortex; these structures showed greater activation when the subject was attending to pain (see Apkarian et al3 for a review). Figure 11-1 shows that the SI cortex is more activated by noxious stimuli when subjects are required to attend to the pain than when they attend to an auditory stimulus. Thus, simply distracting a patient from pain can have profound consequences in how the pain is processed in the brain.

Fig 11-1 Pain-related activity in SI cortex when a subject’s attention is directed to a painful heat stimulus (left) or to an auditory stimulus (right). Activity was determined by subtracting positron emission tomography (PET) data recorded when a warm stimulus (32°C to 38°C) was presented from those recorded when a painfully hot stimulus (46.5°C to 48.5°C) was presented during each attentional state. Adapted from Bushnell et al.6

Our Emotions Affect Our Perception of Pain

Mood and emotional state also affect pain perception; negative emotions lead to more pain than positive emotions. Clinical studies have shown that emotional states and attitudes of patients influence pain that is associated with chronic diseases.7 In the experimental context, manipulations that positively affect mood or emotional state, such as pleasant music, odors, pictures, and humorous films, generally reduce pain perception; whereas those that negatively affect mood and induce negative emotions, such as anxiety, increase pain perception.2

What Are the Mechanisms by Which Attention and Emotions Alter Pain?

The neural mechanisms underlying attentional and emotional modulation of pain and the changes in activity of the cortical areas subserving pain perception are not fully known, but they most likely involve various levels of the central nervous system (CNS). An opiate-sensitive descending pathway from the frontal cortex to the amygdala, periaqueductal gray (PAG), rostral ventral medulla, and trigeminal brain stem sensory nuclear complex (VBSNC) and spinal cord dorsal horn has been implicated in psychologic modulation of pain (see chapter 8). Some researchers have suggested that this pathway is involved in attentional modulation of pain, but these studies have typically used tasks that />

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses