Mucosal diseases

11.1 Normal oral mucosa

Three divisions of oral mucosa are recognised.

Normal structures

11.2 Conditions related to friction or trauma

Frictional keratosis

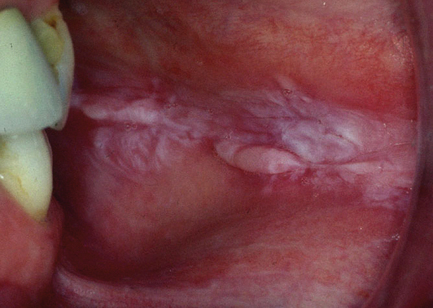

Chronic mechanical, thermal or chemical trauma may induce a keratinising response in buccal mucosa (which is normally non-keratinising) and hyperkeratosis (excessive keratinisation) elsewhere (Fig. 11.1). This may occur through activation of keratin genes. The keratin becomes swollen, resulting in a spongy appearance. Diagnosis is clinical and treatment normally involves eliminating the cause and reviewing to ensure resolution. There may be a local cause such as a sharp tooth or it may be habit related. Biopsy is undertaken where doubt exists. The principal histopathological features are:

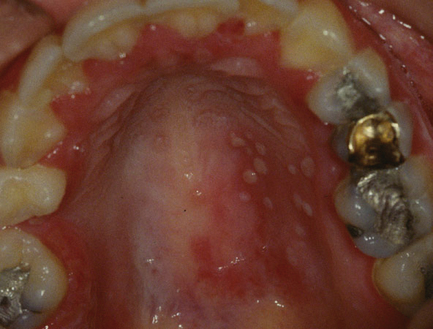

Smoker’s palatal keratosis

Smoker’s palatal keratosis is also known as stomatitis nicotina. It is associated with any smoking habit but tends to be most florid in pipe smokers. The clinical appearance is considered to be diagnostic and biopsy is not normally indicated. The diagnosis is restricted to palatal lesions. The principal features are:

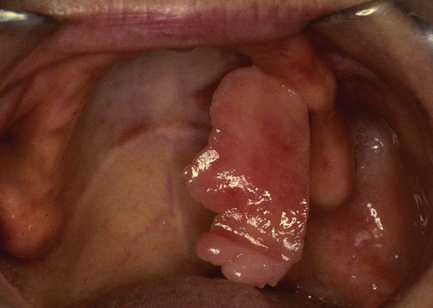

Fibroepithelial polyp

A fibroepithelial polyp is typically a firm sessile or pedunculated polyp that arises most commonly on the labial and buccal mucosa as a result of mechanical trauma from the teeth or dentures (Fig. 11.2). It is easily excised under local analgesia but will recur unless the source of trauma is corrected.

Connective tissue neoplasms

Connective tissue neoplasms are uncommon in the oral mucosa, but benign tumours including lipoma, neuroma and fibroma may occur and mimic fibrous hyperplasia clinically. Malignant soft tissue neoplasms are extremely rare but may arise from any connective tissue in the oral cavity.

11.3 Ulceration

Oral ulceration is commonly caused by mechanical trauma. It is also associated with systemic diseases, drug side-effects and with infections (see Section 11.4).

Traumatic ulceration

On clinical examination, traumatic ulcers typically are painful and surrounded by erythema. The base is covered by fibrinous exudate and at a later stage by granulation tissue and regenerating epithelium (see Fig. 2.5, p.19). Shape and location often give a clue as to the cause. On gentle palpation, traumatic ulcers lack induration and are tender.

Recurrent aphthous stomatitis: aphthous ulceration

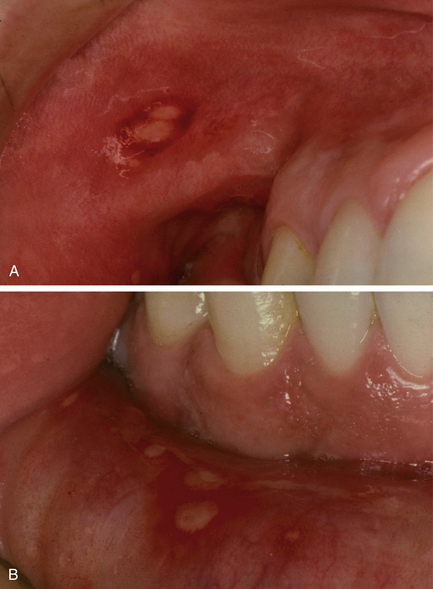

Minor RAS: Ulcers are up to 10 mm in diameter with a yellow–grey base and halo of erythema (Fig. 11.3). It affects only non-keratinised mucosa. Ulcers tend to occur in crops of one to five but variable patterns are seen, ranging from occasional single ulcers to over 20 at any one time. Individual ulcers heal without scarring in 10–14 days.

Herpetiform RAS: Pinhead-size ulcers occur in crops of more than 20 at a time (Fig. 11.4). Typically, the ulcers become confluent and healing normally occurs within 14 days. Any mucosal site can be affected. The severity of symptoms is greater than in minor RAS, with some patients experiencing a continuous pattern of ulceration.

Major RAS: Ulcers are normally at least 10 mm in diameter (Fig. 11.5). They persist for a minimum of 4 weeks with one to three ulcers normally being present at a time. They often heal with scarring. Any mucosal site can be involved; often the oropharynx is affected. This causes particularly severe symptoms, including pain on swallowing and gagging.

Aetiology

The aetiology of RAS is unknown, though there are strong associations with having a family history of RAS, stress, smoking cessation, anaemia and haematinic deficiency. RAS is also seen in gastrointestinal disease, particularly Crohn’s disease (which may involve the oral mucosa directly or induce oral ulceration secondary to malabsorption), coeliac disease and other disorders of malabsorption. Oral ulceration is additionally observed in immunological disorders. Behçet’s disease is a multisystem autoimmune disorder for which RAS is one of the major diagnostic criteria. Classically, it is accompanied by genital ulceration and eye lesions (e.g. uveitis); however, the skin, joints, gastrointestinal tract, blood vessels and central nervous system may also be affected in various combinations. Severe unusual RAS is a recognised manifestation of infection with the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV).

Diagnosis

The diagnosis of RAS is made on clinical grounds. Because of its association with disease of the gastrointestinal tract, specific enquiry should be made into signs and symptoms of gastrointestinal problems. Similarly, the possibility of Behçet’s disease leads to enquiry concerning the presence of other signs and symptoms of this disease. A full blood count and haematinics (serum vitamin B12, ferritin (an iron-binding protein), folate) should be carried out. Where vitamin B12 deficiency is detected, the possibility of pernicious anaemia should be investigated by checking the blood for antibodies to intrinsic factor. Low levels of ferritin, in the absence of the an apparent cause such as blood loss from the gastrointestinal or genitourinary tract, are suggestive of coeliac disease and the patient’s blood should be checked for the presence of endomyseal or tissue transglutaminase antibody. Coeliac disease has a prevalence of 0.5–1% in the population and may be diagnosed in children and adults. Other causes of folate deficiency (e.g. alcoholism) and vitamin B12 deficiency (e.g. diet) should also be considered. The most common cause of a low ferritin level is chronic blood loss. While correction of haematinic deficiencies can bring about resolution or improvement of the patient’s oral ulceration, this is pointless if the underlying cause of the deficiency is not addressed.

Management

It is difficult to prevent ulceration from occurring in susceptible individuals; however, limiting trauma to the oral mucosa by eliminating sharp foods, in particular crisps, from the diet can be of benefit. Similarly, where trauma from the teeth as a result of parafunctional habits is suspected, the provision of a soft bite guard for night-time wear may help. The use of a sodium lauryl sulphate-free toothpaste may also be of benefit. Unfortunately, the treatment of RAS lacks a robust evidence base. In terms of medication, some relief of symptoms may be obtained by the use of benzydamine mouthwash or spray. Both chlorhexidine and doxycyclin mouthwashes can be of benefit; the latter seems to be of particular value in the treatment of herpetiform ulceration. Topical steroid preparations are widely used (see Section 11.5) and betamethasone mouthwash to be particularly effective, if used on a daily basis, when episodes of ulceration are frequent. For severe cases, systemic medication is indicated, for example thalidomide, colchicine or systemic steroids; such agents should only be prescribed by a hospital-based specialist.

11.4 Infections

Viral infections

Oral involvement in herpes simplex (HSV) infection is commonly encountered, especially in children, and is most often due to HHV-1 (Fig. 11.6).

Primary herpetic gingivostomatitis

Initial infection results in primary herpetic gingivostomatitis. Grey blisters, which rapidly break down to form small ulcers, may be present anywhere on the oral mucosa and most frequently involve the gingivae. Crusted blisters may also appear on the circumoral skin. Infection is usually accompanied by a febrile illness, and bilateral tender cervical lymphadenopathy is frequently present. Infection can be spread to the fingers and conjunctiva by direct contact with the oral lesions, and advice should be given to avoid this. Resolution occurs within 2–3 weeks. Rest, maintaining fluid intake, analgesics, chlorhexidine mouthwash to prevent secondary infection of the oral lesions and advice about cross-infection risks should be given. Infants under 6 months are at special risk of developing central nervous system infection and contact with infected siblings should be avoided. Prescription of systemic aciclovir is only of benefit in the early stages of the infection; a reasonable guide to this is the presence of intact vesicles. Diagnosis is usually made on clinical grounds, where doubt exists, serology performed on samples of acute and convalescent (2–3 weeks after onset of symptoms) blood should reveal a significant rise (of the order of four-fold or greater) in IgG antibodies against HSV in the later sample. Swabs, for culture or identification of viral DNA by polymerase chain reaction (PCR), and smears for cytology (showing ballooning of epithelial nuclei and/or multinucleate epithelial cells) may be useful but usually only if taken early in the course of the disease, ideally from an intact vesicle.

Herpes zoster

Herpes zoster (HHV-3), the causative agent of chickenpox and shingles (Chapter 14), may involve the oral mucosa. Shingles tends to affect one or more dermatomes of the trigeminal nerve and is an important cause of facial pain (Chapter 14). In the oral mucosa, rashes of grey vesicles restricted to the distribution of the sensory nerves are seen. High-dose systemic aciclovir or famciclovir is usually prescribed.

Human papillomavirus

Human papillomaviruses (low risk types) produce focal proliferative lesions referred to as squamous papillomas (warts). They may be sessile or show finger-like projections. Histologically, fronds of keratotic squamous epithelium are supported by delicate fibrovascular stroma. Papillomas on the fingers can be the source of human papillomavirus, particularly for lesions on the lips and circumoral skin. Orogenital transmission is also possible. Intraoral papillomas can be readily excised under local analgesia. The high risk HPV types 16 and 18 are an important cause of oropharyngeal carcinoma (see Chapter 12).

Human immunodeficiency virus

Kaposi’s sarcoma: This is caused by human herpesvirus 8 (HHV-8), which is endemic in Mediterranean regions. Initial mucosal lesions are flat brown spots, which show haemosiderin deposition and vascular proliferation on biopsy. They progress into raised plaques and then nodular purple–red lesions, most often found on the palate, retromolar areas and gingivae. Oral lesions may precede the appearance of skin lesions.

Hairy leukoplakia: This lesion has been associated with progression from HIV infection to AIDS (acquired immunodeficiency syndrome) as the CD4 T lymphocyte count falls. It is caused by proliferation of Epstein–Barr virus (HHV-4) in the lateral tongue epithelium and rarely elsewhere in the oral cavity. Warty ridged or smooth white plaques are typical: sometimes extended papillary projections are seen. The lesion is also found in HIV-negative immunosuppressed patients, for example in renal transplant recipients. Hairy leukoplakia has been recorded in patients taking a variety of drugs, including steroid inhalers, and HHV-4 may also be a transient mucosal infection in healthy people. No treatment is required and the lesion is not potentially malignant.

Erythematous candidiasis: This is a frequent manifestation of HIV infection. It presents as white speckles on an erythematous background. Tongue and palate are frequently affected. Treatment can be a problem because of the development of resistant fungal strains in some patients. Hyperplastic and pseudomembranous forms of candidiasis are also common in HIV infection.

HIV-related gingivitis: This may resemble acute necrotising ulcerative gingivitis or present as a red lesion, termed linear gingival erythema.

Fungal infections

Candida albicans is the most common cause of fungal infection in the oral cavity (Fig. 11.7). It is a commensal organism carried by roughly half the population and disease is caused by opportunistic overgrowth. Oral candidiasis has been described as the ‘disease of the diseased’. Local or systemic predisposing factors should be identified and corrected whenever possible (Table 11.1). Diagnosis is generally based on clinical features and can be confirmed by laboratory methods using material from oral swabs, smears or rinses. Where quantification is required, saliva samples, the oral rinse or the imprint culture techniques may be used. Other Candida sp. may also cause oral infection, particularly in the immunocompromised.

Table 11.1

Classification of Candida-related oral lesions

| Lesion | Characteristics |

| Thrush (acute pseudomembranous candidiasis) | Friable white plaques that can be scraped off; often involves oropharynx; affects infants, elderly and immunosuppressed adults |

| Antibiotic sore mouth | Generalised erythematous and sore oral mucosa; caused by elimination of bacterial competition; related to prolonged use of wide-spectrum antibiotics |

| Denture-induced candidiasis | Related to continuous wearing of acrylic dentures; mucosa over fitting surface appears erythematous and oedematous; patient should improve denture hygiene and leave dentures out at night |

| Chronic hyperplastic candidiasis | Fixed, white, folded plaques, commonly behind the angle of the mouth; smoking and poor denture hygiene are common predisposing factors; candidal hyphae invade the parakeratin layer |

| Erythematous candidiasis | Red patchy areas, typically on palate and dorsum of tongue; associated with low CD4-cell counts, particularly in HIV infection; may be a cause of linear gingival erythema |

| Angular cheilitis | Crusted cracked lesions at the angle of the mouth; may be infected by Candida sp. or Staphylococcus aureus; predisposing factors include anaemia and saliva spreading to skin |

| Median rhomboid glossitis | Lozenge-shaped erythematous patch on the midline dorsal tongue; usually symptomless; epithelial hyperplasia with neutrophils in the parakeratin layer |

| Mucocutaneous candidiasis | Generalised chronic oral candidiasis resulting in fixed mucosal white patches; immune defect may be detected but sometimes idiopathic; some types associated with endocrine or thymus disease; nails often affected, other mucosal sites may also be involved |

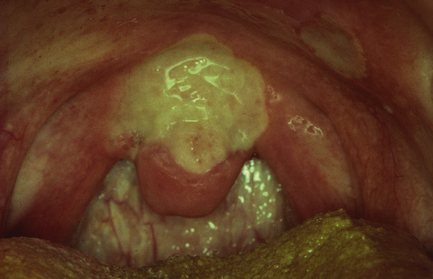

Fig. 11.7 Denture-related stomatitis.

The oral mucosa of the denture-bearing area is erythematous, oedematous and hyperplastic. Candida albicans was recovered from the fitting surface of the denture.

Systemic antifungal agents (e.g. fluconazole) should be reserved for those cases of oral candidiasis where topical antifungal agents are not appropriate. There are an increasing number of reports of resistance to azole antifungal drugs. These drugs play a significant role in the treatment of candidal infections in the immunocompromised. In contrast to nystatin, triazole or imidazole antifungal agents, including miconazole gel, are readily absorbed via the gastrointestinal tract thus care should be taken to check for possible drug interactions.

Chronic hyperplastic candidiasis

• Epithelial acanthosis and parakeratosis resulting in broad, blunt rete processes.

• Candidal pseudohyphae penetrate the parakeratin layer.

• Neutrophils form microabscesses in the parakeratin layer.

• Intense diffuse chronic inflammatory infiltrate present in the lamina propria.

• May regress following elimination of local predisposing factors and antifungal therapy (systemic unless contraindicated).

• If microscopic dysplasia found (40% cases) then the lesion may be clinically classified as candidal leukoplakia.

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses