Chapter 11

Dental Implants Therapy

INTRODUCTION

The history of implants and their surgical placement, indications, healing process, etc. have been discussed in great detail in a previous book (Dibart, 2007). The purpose of this chapter is a little bit more challenging. What evidence do we have that the treatments we are rendering are really necessary or effective? And if so, how effective? We looked at systematic reviews in our attempt to answer these questions in light of the most recent evidence-based research literature available. Such reviews of the existing literature can be found in various databases (MEDLINE, Cochrane, EMBASE). Several authors have described the value of systematic reviews in dental research, and as a result they have been recognized as powerful research tools in evidence-based dentistry. Systematic reviews are inherently less biased, more reliable, and more valid than narrative reviews (Carr, 2002; Bader, 2004). The treatment decisions we make need to be based on the scientific study of clinical outcomes taken from properly documented and executed clinical research.

INDICATIONS

Implant therapy is aimed at replacing natural teeth that have been lost in the past or had to be recently extracted, leaving an area edentulous. So let us look at a few reasons why we would need to extract natural teeth. The decision to extract is made when the restorability of the tooth is in doubt. The usual scenario involves incipient or recurrent caries, trauma, endodontic failure, root fracture, and periodontal disease.

EVIDENCE-BASED OUTCOMES

The Tooth Extraction Dilemma: Root Canal Therapy, Fixed Partial Denture, or Implant-supported Crown?

There are enormous benefits in retaining a natural tooth; we have to remember that we, as periodontists, have the duty to preserve the natural dentition as long as possible and that dental implants, as wonderful as they are, may never replace fully natural teeth. The advantages of retaining a natural tooth include:

- Preservation of the alveolar bone

- Preservation of the papilla

- Preservation of pressure perception

- Preservation of natural structures (crown, root)

- Lack of movement of the surrounding teeth

Torabinejad et al., in 2007, after a thorough systematic review of the literature, tried to compare the long-term success rate of endodontic treatment vs. fixed partial denture (FPD) or implant-supported crown (ISC). This proved to be an arduous task, because the evidence identified by the authors did not permit them to definitively answer all of the questions posed. The evidence available for answering the questions came from mainly indirect comparisons, hence the warning that these conclusions are tentative and that there is a need for additional studies.

The concept of success is also reported differently in the literature when we compare the outcomes of RCT, FPD, or implant-supported crowns (ISC). An implant that has had some marginal bone loss and is still functional is not generally considered a failure, whereas FPD’s failure can be reported as presence of recurrent decay, root fracture, porcelain fracture, loss of retention, etc. The endodontic literature is far more precise in documenting/defining success and failure. Because RCT is aimed at treating an existing disease, the evaluation of a successful outcome via radiographic monitoring or patient’s lack of symptoms is much easier.

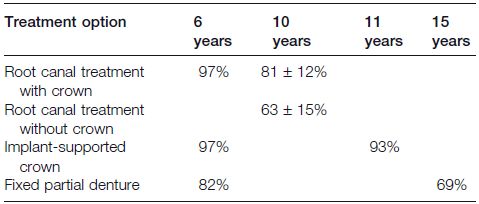

In Torabinejad’s analysis, looking at 6+ years follow-up, the weighted survival data indicated that in patients with periodontally sound teeth having pulpal and/or periradicular pathosis, root canal therapy resulted in a survival rate of 97% (Table 11.1). The same rate (97%) was also found for extraction and replacement of a missing tooth with an implant. On the other hand, an extraction and replacement with FPD had a survival rate of 82%, well below that of RCT and ISC at six years. The authors also reported that FPD success rates continued to drop steadily over time beyond 60 months. This was confirmed by another review of the literature, by Salinas et al. (2004), which stated that at 15 years the rate of survival of the FPD had dropped to 69%, whereas at 11 years the cumulative success rate for implants was 93% (Naert et al., 2000). This indicates that an implant-supported crown would be the better choice when deciding on how to restore a missing tooth in a dentition.

In 2007, Stavropoulou and Koidis conducted a systematic review of the literature to test the hypothesis that the placement of a prosthetic crown on an endodontically treated tooth was associated with improved survival rates. They found that the cumulative survival rates after 10 years for RCT with crowns and RCT without crowns were 81 ± 12% and 63 ± 15%, respectively. Hence, the necessity to crown the teeth that have been endodontically treated.

Table 11.1. Comparative long-term survival rates of root canal treatment plus crown, root canal treatment without crown, implant-supported crown, and fixed partial denture.

Author’s Views/Comments: The longevity of the classical treatment—RCT, possible crown lengthening when needed, and prosthetic crown—depends on the quality of each of the steps performed by the general dentist or the specialists involved. Not all dentists are created equal, hence the variability of long-term success/survival. It is much easier and less technique-sensitive to remove a questionable tooth and place an implant followed by a crown.

Dental Implant Placement: Immediate, Immediate Delayed, or Conventional Delayed Placement?

Dental implants can be placed in fresh extraction sockets, just after tooth extraction. These are called immediate implants. They have the advantage of shortening the treatment time for the patient as well as reducing the number of surgical procedures. They also can be placed without raising a flap in most cases. The disadvantages are enhanced risk of infection and failure, the presence of a gap between the implant and alveolus, and the necessity sometimes of bone grafting (Rosenquist, 1997; Takeshita, 1997). An alternative is the immediate-delayed option. These implants are placed in the healing socket after four to eight weeks to allow for the soft tissue healing that will permit primary closu/>

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses