10 Malignant disease of the oral cavity

ASSUMED KNOWLEDGE

It is assumed that at this stage you will have knowledge/competencies in the following areas:

INTENDED LEARNING OUTCOMES

At the end of this chapter you should be able to:

ORAL AND OROPHARYNGEAL CANCER

Reconstruction

Primary reconstruction is now the rule, and this is to the great benefit of patients. Earlier techniques were often unreliable and when bony reconstruction was involved it was often delayed. It was reasonably felt that before embarking on such prolonged and insecure techniques a period of time should be allowed to elapse, to demonstrate that local recurrence was unlikely before reconstruction was attempted. With current techniques based largely on muscle flaps—pectoralis major, trapezius and latissimus dorsi—and free tissue transfer based on microvascular techniques—radial forearm, lateral thigh, scapular, fibula and groin—primary reconstruction is not only reliable but produces acceptable functional and cosmetic results.

Radiotherapy

Although treating a cancer with radiotherapy avoids major surgery it has disadvantages:

Clinical aspects

Oral cancer has a predilection for certain sites within the mouth, mostly the lateral margins and ventral tongue, floor of mouth, retromolar trigone, buccal mucosa and palate. Most—more than 85%—are mucosal squamous cell carcinomas. Malignant tumours arising in the minor salivary glands are next in frequency, with lymphomas, malignant melanomas, sarcomas and metastatic tumours making up the remainder.

PREMALIGNANT LESIONS

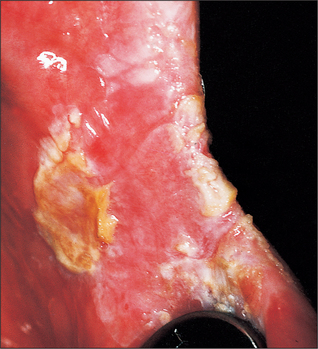

Leukoplakia (Fig. 10.1)

Potential for malignant change

The incidence of malignant change in oral leukoplakia increases with the age of the lesion. One study showed a 2.4% malignant transformation rate at 10 years, which increased to 4% at 20 years. It also showed that as the age of the patient increased so did the risk of malignant transformation: for patients younger than 50 years it was 1%, whereas for those between 70 and 89 years it was 7.5% during a 5-year observation period. Kramer et al. (1978) have shown that in Southern England leukoplakia of the floor of the mouth and ventral surface of the tongue, so-called ‘sublingual keratosis’, has a particularly high incidence of malignant change. Their study suggested that this occurrence was due to pooling of soluble carcinogens in the ‘sump’ of the floor of the mouth.

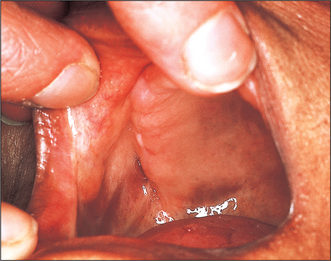

Oral submucous fibrosis (Fig. 10.4)

Oral submucous fibrosis is a progressive disease in which fibrous bands form beneath the oral mucosa. These bands progressively contract so that ultimately opening is severely limited, speech becomes hypernasal due to changes in the soft palate and swallowing is disturbed. Tongue movement may also be limited. The condition is almost entirely confined to Asians. Histologically it is characterized by jux-taepithelial fibrosis with atrophy or hyperplasia of the overlying epithelium, which also shows areas of epithelial dysplasia. Paymaster, in 1956, first discussed the precancerous nature of submucous fibrosis (see Langdon and Henk 1995). He noted the onset of a slowly growing squamous cell carcinoma in one-third of such patients. The changes are due to crosslinking of the collagen fibres caused by various alkaloids, particularly arecholine, which leach out of the arecha nut and penetrate the oral mucosa.

Syphilitic glossitis

Before the antibiotic era, syphilis was an important predisposing factor in the development of oral leuko-plakia and oral cancer. The syphilitic infection produces an interstitial glossitis with an endarteritis that results in atrophy of the overlying epithelium. This atrophic epithelium appears to be more vulnerable to those irritants that cause oral cancer or oral leukoplakia. As these changes are irreversible there is no specific treatment, although active syphilis must be tre/>

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses