Chapter 10

Generalised Gingival Recession

Aim

To describe the appearance and discuss the aetiology, investigation and periodontal management of systemic diseases that manifest clinically as generalised gingival recession.

Outcome

Having read this chapter, the clinician should be aware of the systemic diseases that may give rise to generalised gingival recession, either directly as a result of the biology of that disease process, or secondary to aggressive periodontal disease, which is a component of that systemic condition. Table 10-1 lists the most common causes of generalised gingival recession, but this chapter will limit discussion to recession associated with underlying systemic diseases. Most of these conditions are uncommon and patients should be referred for specialist management, rather than being managed in general practice.

| Condition | Sub-Category | Nature | Incidence | Manage/Refer |

| Trauma | Toothbrush | Facial surfaces | common | manage |

| Trauma | e.g. de-gloving injury | uncommon | manage | |

| Occlusion | Traumatic class 2 Div II (gingival stripping) |

common | manage/refer | |

| Periodontal disease | Untreated | common | manage | |

| Treated | common | manage | ||

| Systematic disease with generalised recession as Manifestation due to destructive periodontitis | Down syndrome | Trisomy chromosome 21 | common | manage |

| Papillon-Lefevre syndrome (PLS) ± Haim Munk syndrome | Genetic mutation of blood neutrophil gene for enzyme Cathepsin C | uncommon | refer | |

| Hypophosphatasia | Genetic defect in gene for enzyme alkaline phosphatase | uncommon | refer | |

| Chronic granulomatous disease (CGD) | Genetic defect – failure of neutrophils to kill bacteria | uncommon | refer | |

| Chèdiak-Higashi syndrome | Genetic defect of neutrophil function | uncommon | refer | |

| Ehlers-Danlos syndrome | Genetic defect of collagen metabolism | uncommon | refer | |

| Leukocyte adhesion deficiency (LAD) | Genetic defect of neutrophil affacting ability to adhere | uncommon | refer | |

| Acatalasia | Genetic defect of catalase production in red blood cells | uncommon | refer | |

| Infantile genetic agranulocytosis | Severe neutropaenia | uncommon | refer | |

| Agamma/hypogammaglobulinaemia | IgG2 and IgG4 deficiency | uncommon | refer | |

| Cohen syndrome | Complex genetic syndrome | uncommon | refer | |

| Glycogen storage disease | Defect of glygogen metabolism – neutropaenia | uncommon | refer | |

| DiGeorge syndrome | T-cell defects | uncommon | refer | |

| Wiskott-Aldrich syndrome | T & B-cell defects | uncommon | refer | |

| Histiocytosis | Malignant neoplasm of CD-1a cells i.e. Langerhans cells/ histiocytes/ macrophages | uncommon | refer | |

| Systemic disease with recession as manifestation independent of periodontitis | Progressive systemic sclerosis (scleroderma) | Connective tissue disorder | uncommon | refer |

| Drug-induced lesions | Cyclophosphamide | Alkylating drug | uncommon | refer |

| Methotrexate | Cytotoxic drug | uncommon | refer | |

| Cocaine | Recreational drug | uncommon | refer | |

| Bleomycin | Anti-tumour drug | uncommon | refer | |

| Vincristine/ Vinblastine |

Alkaloid drugs | uncommon | refer |

Background

Gingival recession refers to a situation arising where the gingival margin lies apical to its true position in ‘pristine health’. Fig 10-1 illustrates pristine health, which is very rare and quite distinct from ‘clinical health’. In clinical health, it is generally accepted that very subtle signs of mild inflammation will be evident at isolated sites and that variations in normal anatomy may result in a dento-alveolar complex with investing periodontal tissues that are not ‘classical’ in appearance. Fig 10-2 is an example of clinical health, where a midline diastema between the lower incisors provides a non-classical appearance of the interdental papilla and the papilla LL12 has evidence of very mild clinical inflammation.

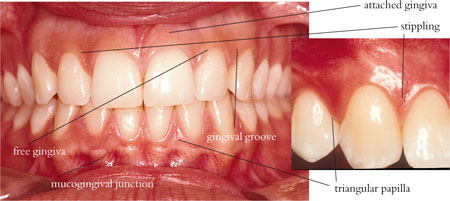

Fig 10-1 An anterior view of ‘pristine gingivae’, demonstrating applied anatomical features from Fig 10-3.

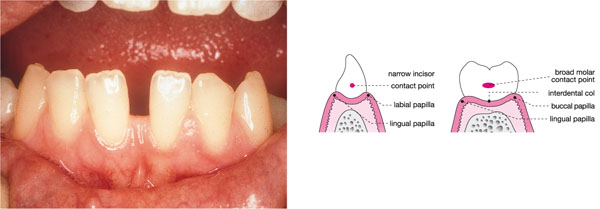

Fig 10-2 Clinical photograph of healthy gingivae, demonstrating the effect of the tooth contact area in dictating interdental papilla shape. The schematic diagrams show the narrow contact point and narrow col between incisors and the broader contact and deeper, more vulnerable col area between molar teeth.

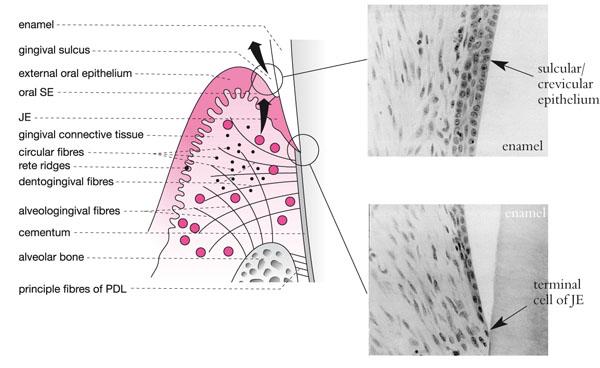

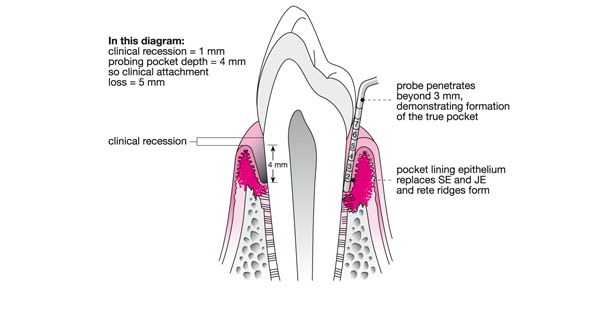

The detailed anatomy of the dento-gingival complex is discussed in book 1 of this series (Chapple and Gilbert, 2002), and further discussion is not within the remit of this book. However, Fig 10-3 illustrates the normal anatomy of this area and Fig 10-4 provides the reader with a reminder of the contribution of recession to overall periodontal attachment loss. In health, the gingival margin lies on enamel 2–3mm above the position of the terminal cell of the junctional epithelium (JE, Fig 10-3). The JE lies at the cemento-enamel junction (CEJ) and the interval between the terminal cell of the JE and the gingival margin is bordered by JE and sulcular epithelium, which form the soft tissue boundary to the gingival crevice. The crevice can be probed up to a distance of 3mm in health. Clinical attachment loss (CAL) due to periodontitis may arise without recession, by true pocket formation (Fig 10-4), but when the gingival margin migrates to a position apical to the CEJ, recession occurs and contributes, with true pocketing, to overall CAL. The gingival margin may lie at the CEJ, and in this situation there is no recession, but clearly the full clinical crown is exposed and attachment loss has taken place.

Fig 10-3 A schematic view of the gingivae demonstrating the gingival collagen fibre complexes. The sulcular (SE) and junctional epithelium (JE) are also represented alongside in two photomicrographs demonstrating normal histology. Note how widely spaced the cells are and how they thin out, forming a single ‘terminal cell’ of the apex of the JE.

Fig 10-4 Schematic longitudinal section of a premolar and associated periodontal tissues, demonstrating early true pocket formation, detected by probing and recession contributing to overall attachment loss.

Aetiology of Gingival Recession

The most common cause of gingival recession is toothbrush trauma. This classically presents buccally to posterior teeth at the facial surfaces and not the interproximal surfaces. Interproximal recession generally implies CAL due to true periodontitis. Other common causes of generalised recession include:

-

untreated periodontal disease (Fig 10-5).

-

effects of successful periodontal therapy (Fig 10-6).

-

trauma from the occlusion (usually labial stripping of gingivae labial to the lower incisors or palatal to upper incisors in a traumatic class II division 2 malocclusion (see Noble, Kellett and Chapple, 2004).

-

physical trauma from an accident (de-gloving injuries from blunt trauma e.g. steering wheel or fist).

Fig 10-5 Generalised recession due to progressive untreated chronic periodontitis.

Fig 10-6 Generalised gingival recession following successful periodontal therapy and supportive care. A Maryland bridge has been fabricated to replace LR2, which was lost to periodontal disease.

This chapter will focus on recession due to periodontal attachment loss that has arisen:

-

secondary to systemic disease where destructive periodontitis is a manifestation of that disease.

-

directly as a manifestation of a systemic disease, even in the absence of significant inflammatory periodontitis (e.g. systemic sclerosis, drug-induced recession).

Systemic Disease with Generalised Recession as Manifestation Due to Destructive Periodontitis

Down Syndrome

Clinical appearance

-

Generalised recession upper and lower incisors.

-

Severe periodontal destruction and pocketing (Fig 10-7).

-

Gingival inflammation.

-

Severe radiographic bone loss affecting upper and lower incisors.

-

Short roots to lower incisors.

-

Tooth mobility.

Fig 10-7 Periodontal disease and gingival inflammation in a patient with Down syndrome.

Clinical symptoms

-

Gingival bleeding.

-

Tooth mobility (especially lower incisors).

-

Impaired eating/function.

Aetiology

Down syndrome, first described by Langdon-Down, is a complex syndrome whose genetic basis is trisomy of chromosome 21. The cause of the periodontal destruction, which is reported to affect between 60–90% of subjects is also complex and thought to involve:

-

Poor oral hygiene (especially in institutionalised individuals).

-

Defects of PMNL function (chemotaxis, phagocytosis and killing).

-

Depressed T-cell induced antigen killing.

-

B-lymphocyte receptor defects.

-

Abnormal collagen biosynthesis.

Involvement of non-gingival sites

-

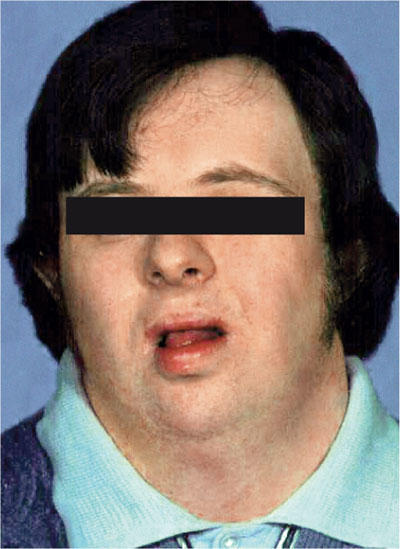

Characteristic facial appearance (Fig 10-8).

-

Learning difficulties.

-

Short stature.

-

Cardiac defects (may need antibiotic cover).

-

Class III malocclusion.

-

Anterior open bite.

-

Macroglossia.

-

Anterior tooth crowding.

Fig 10-8 The patient from Fig 10-7.

Fig 10-9 A two-year-old Pakistani boy with recession and early mobility of upper and lower deciduous incisors due to Papillon-Lefèvre syndrome (PLS).

Differential diagnosis

Given the obvious clinical presentation and medical history, no other differential diagnoses are likely.

Clinical investigation

-

Standard periodontal investigations.

Management options

-

Behavioural management.

-

Non-surgical periodontal therapy.

-

Rigorous supportive care.

-

Cardiological opinion in case antibiotic prophylaxis is needed for invasive procedures.

Papillon-Lefèvre Syndrome

Clinical appearance

Generally presents between the ages of two and seven years with one or more of the following, which affect the deciduous and permanent dentition:

-

Generalised recession affecting deciduous incisors (Fig 10-10).

-

Premature tooth mobility.

-

Spacing and drifting of anterior teeth (Fig 10-10).

-

Severe generalised gingival inflammation (Fig 10-11).

-

Severe periodontal destruction radiographically (Fig 10-12).

-

Radiographic bone loss where apices of permanent teeth are not yet fully formed.

Fig 10-10 Spacing and drifting on the anterior permanent incisors in a seven-year old boy with PLS and severe periodontal disease.

Fig 10-11 Severe gingival inflammation in a six-year old boy, with grade II mobility of the central incisors.

Fig 10-12 Substantial bone loss affecting the permanent dentition of the patient in Fig 10-11.

Patients generally progress to total tooth loss by 20 years of age.

Clinical symptoms

-

Gingival recession.

-

Tooth mobility.

-

Gingival bleeding.

-

Tooth spacing.

-

Recurrent abscesses/infection.

Aetiology

Papillon-Lefèvre syndrome (PLS) is an inherited autosomal recessive disorder, characterised by a strong family history of consanguinity (Fig 10-13). It has a prevalence of one in four million, most common in Indo-Pakistani children, and classical signs usually appear between two and four years of age. It arises from a gene defect, recently mapped to the long arm of chromosome 11 (11q) and results in the loss of function of an important neutrophil (PMNL) enzyme called Cathepsin-C. Cathepsin-C is a lysosomal enzyme found in the primary granules of PMNLs that is important in bacterial destruction and is expressed in the skin of the feet and hands, as well/>

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses