CHAPTER 10 EFFECTIVE COMMUNITY PREVENTION PROGRAMS FOR ORAL DISEASES

Oral diseases have been referred to as “the neglected epidemic” because they affect almost the total population, with many people having new diseases each year.1 For example, at age 6 years only 5.6% of U.S. schoolchildren have had tooth decay in their permanent teeth. However, by age 17 years, 84% have had the disease with an average of eight affected tooth surfaces (for more information about the epidemiology of dental caries, see Chapters 2 and 8).2 For vulnerable populations, such as those with low incomes, minorities, the developmentally disabled, and persons with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS), the extent of oral disease is even greater. The national goal for oral health as stated in Healthy People 2010 is to “prevent and control oral and craniofacial diseases, conditions, and injuries and improve access to related services.”3 The oral health objectives shown in Box 10-1 are intended to prevent, decrease, or eliminate oral health disparities in the U.S. population. Yet our country has not made oral health a priority.4 Further, the United States does not have a national oral disease prevention program, despite an estimated $65 billion annual dental bill.5 Compounding the problem, a 1996 study of children eligible for Medicaid reported that only one out of five, or 20%, received dental treatment, and a 2000 study showed that most dentists do not participate in Medicaid.6,7 Despite the progress made in the prevention of oral diseases in the last several decades as a result of community water fluoridation, use of other fluorides, and greater emphasis on prevention in general, much more remains to be done.

BOX 10-1 Healthy People 2010 Oral Health Objectives

From the US Department of Health and Human Services: Healthy People 2010: with understanding and improving health objectives for improving health, ed 2, Chapters 1, 3, 5, and 21, Washington, DC, US Government Printing Office.

Numbering in box indicates the chapter and objective number as listed in Healthy People 2010.

PREVENTION

Prevention of premature death, disease, disability, and suffering should be a primary goal of any society that hopes to provide a decent future and a better quality of life for its people. Primary prevention, or preventing a disease before it occurs, is the most effective way to improve health and control costs. Secondary prevention is treating or controlling the disease after it occurs, such as placing an amalgam restoration. Tertiary prevention is limiting a disability from a disease or rehabilitating an individual with a disability, such as providing dentures for those who have lost all their teeth.

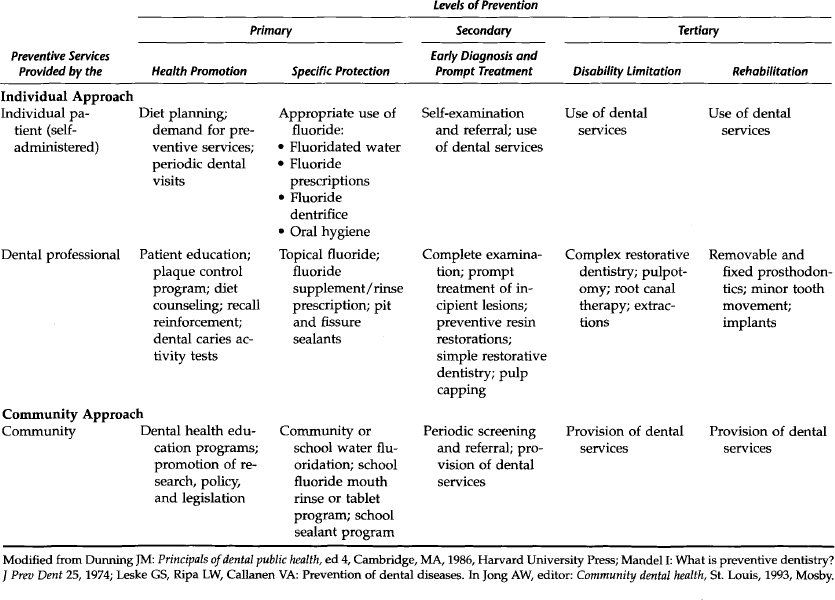

Prevention may be accomplished at the individual or community level. On the individual level a procedure is either provided by a professional on a one-on-one basis, for example, a dental hygienist providing dental sealants for a child patient, or it is self-administered, that is, the patients perform the procedure themselves, such as toothbrushing. An individual procedure also may be a combination of actions of an individual patient and a dental professional, such as the prescription by a dentist of a systemic fluoride that is taken daily by a patient. Table 10-1 shows the three levels of prevention for dental caries at the individual and community level or approach.

DEFINITIONS

To put “effective community prevention programs” in perspective with how prevention is often considered, the following definitions are used for this chapter:8

DENTAL CARIES

Dental caries, or tooth decay, is both a universal and a lifelong disease. This disease is universal in the sense that the prevalence or percent of the population affected increases with age, ultimately affecting almost the entire population. All of us are at risk for caries as long as we have our natural teeth. Thus it is lifelong and may occur as early as the first year of life as early childhood caries (ECC) (sometimes referred to as nursing or baby-bottle tooth decay; see Chapter 7), continue throughout childhood and young adulthood, and continue in adults as root surface caries. During adolescence and into adulthood, the incidence of dental caries continues depending on the level of community, personal, and professional protection; genetic influences; and dietary habits. Approximately 99% of adults have had tooth decay by age 40 to 44 years, with an average of 30 affected tooth surfaces.9 For adults over age 75, nearly 60% had root surface caries with 3.1 affected tooth surfaces.10 Recurrent decay can occur at any time throughout the life cycle. Thus it is important to prevent the onset of the disease because once a tooth has been restored the restoration must be replaced over time, and each restoration becomes larger and larger. Ultimately, costly crowns, root canals, or extractions may be needed.

Prevention of Dental Caries

FLUORIDES

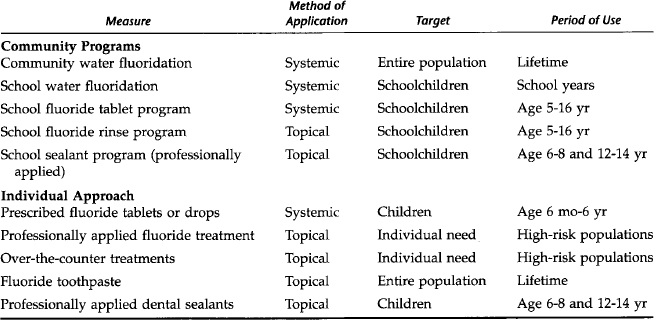

Fluoride is now used in many different ways to prevent dental caries. Table 10-2 shows individual and community preventive measures that have been shown to be effective, the primary mode of application, and the target population. Initially it was believed that the primary anticaries benefit from fluoride was systemic, when the fluoride ion was ingested and became part of the developing tooth, before the tooth erupted in the mouth. The exact mechanisms of action of fluorides are not yet known. There are both preeruptive and posteruptive benefits from fluoride. A recent study from Australia reconfirms the preeruptive benefits from community water fluoridation.11 Major benefits also are a result of posteruptive fluoride levels in plaque, saliva, and gingival exudate that continuously bathe the teeth and increase the remineralization of demineralized enamel caused by acids produced by cariogenic bacteria.

COMMUNITY WATER FLUORIDATION

Community water fluoridation was first implemented in the United States in 1945. Since then, millions of Americans have enjoyed the health and economic benefits of this prevention measure. According to Healthy People 2010, community water fluoridation “is an ideal public health method because it is effective, eminently safe, inexpensive, requires no cooperative effort or direct action, and does not depend on access or availability of professional services. It is equitable because the entire population benefits regardless of financial resources.”3

Further, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) has recognized community water fluoridation as “one of the great public health achievements of the 20th century.”12 Community water fluoridation should be the foundation of oral disease prevention or treatment programs in communities with a central water supply. Community water fluoridation is defined as the adjustment of the concentration of fluoride of a community water supply for optimal oral health. Fluoridation is often referred to as nature’s way to help prevent tooth decay. The recommended level of fluoride for a community water supply in the United States ranges from 0.7 to 1.2 parts per million (ppm) of fluoride, depending on the mean maximum daily air temperature over a 5-year period.13 Thus in a warm climate the fluoride level would be lower, and in a cold climate it would be higher. In the United States most communities are fluoridated at approximately 1 ppm, which is equivalent to 1.0 mg of fluoride per liter of water. To put this concentration in perspective, consider that one part per million is equivalent to 1 inch in 16 miles, 1 minute in 2 years, or 1 cent in $10,000. At this level fluoridated water is odorless, colorless, and tasteless.

Natural Fluoridation.

All water contains at least trace amounts of fluoride. In the United States in 1992 approximately 10 million people lived in 1924 communities with 3784 water systems that are fluoridated naturally at 0.7 ppm or higher.14 The eight states with the most people served with natural fluoridation–6.6 million in 662 communities–are shown in Table 10-3. Texas has the highest, with almost 3 million people in 284 communities.

Table 10-3 Eight Highest-Ranking States by Number of Persons and Communities Served with Natural Water Fluoridation, 1992

| State | Number of Persons | Number of Communities |

|---|---|---|

| Texas | 2,955,995 | 284 |

| Florida | 929,105 | 35 |

| Colorado | 811,024 | 106 |

| Illinois | 442,714 | 127 |

| California | 414,798 | 29 |

| South Carolina | 386,940 | 2 |

| Louisiana | 359,906 | 31 |

| Arizona | 345,266 | 48 |

| total | 6,645,748 | 662 |

Adjusted Fluoridation.

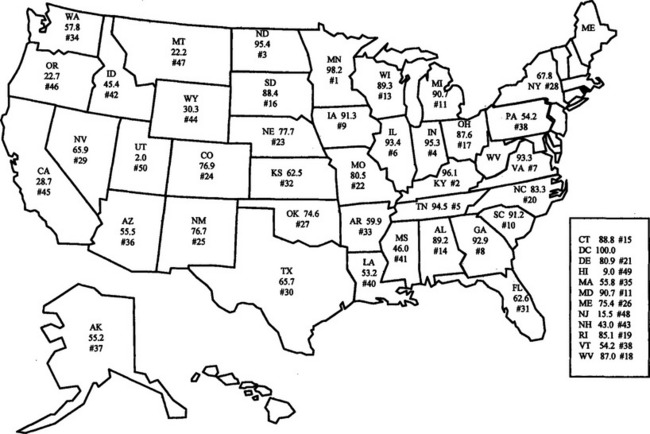

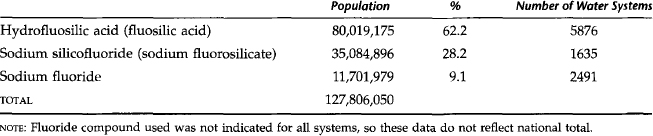

In 1992, 134.6 million Americans had access to adjusted community water fluoridation in 8572 communities with 10,567 water systems compared with approximately 151 million Americans in 2000.14,15 Fig. 10-1 shows the national fluoridation rank of states with the percentage of the population served by adjusted and natural community water fluoridation in 2000. Adjusted fluoridation is accomplished “by adding fluoride chemicals to fluoride deficient water: by blending two or more sources of water naturally containing fluoride, or partial de-fluoridating, that is removing naturally occurring excessive fluoride to obtain the recommended level.”14 There is no difference between adjusted or natural fluoridation in safety or preventive benefits. A fluoride ion is a fluoride ion, whether it occurs naturally in the water supply or whether it is placed or added by a water engineer. The three major fluoride compounds used for fluoridation in 1992 with the population served and number of water systems are given in Table 10-4. The type of compound used depends on the size and type of water facility and the preference of the water supply engineer.16

Table 10-4 Population and Number of Public Water Supply Systems Served by Major Fluoride Compounds, 1992

The United States has more people served by fluoridation than any other country in the world. Consider the following data. In 2000, 162 million Americans, or 65.8% of the 246.1 million on public water supplies, had fluoridation compared with 144.2 million Americans, or 62.1% of the 232 million on public water supplies in 1992.14,15 This is approximately 57.5% of the total U.S. population. More than 119 million Americans did not have access to fluoridation, of whom approximately 35 million were not served by a public water system. Federal government policy requires fluoridation of water supplies on military installations. In 1992, a total of 133 military installations had adjusted fluoridation, serving 1.36 million residents with another 78,528 served by natural fluoridation.14

Of the 50 largest cities in the United States, all but eight have a fluoridated water supply. These eight cities, which have a combined population of approximately 5.4 million people, are San Diego, San Jose, and Fresno, California; Portland, Oregon; San Antonio, Texas; Tucson, Arizona; Honolulu, Hawaii; and Wichita, Kansas. Three of these cities are in California, which passed a statewide fluoridation law in October 1995 requiring fluoridation of all public water systems with at least 10,000 service corrections, depending on available funding. San Diego and San Antonio, respectively, ordered and voted for fluoridation in 2000, but have not yet implemented it. Fresno is partially fluoridated. Tucson, which is partially fluoridated naturally, voted for fluoridation in 1992, but it has yet to be implemented.17

Safety.

The safety of fluoridation has been well documented by numerous studies over the years.18–22 Soon after fluoridation became known as a public health measure, beginning in the 1950s, a variety of diseases and conditions, including premature death, have been alleged to be caused by fluoridation. All have been shown to be false. The following is a partial list of some of the more common conditions falsely attributed to fluoridation: AIDS, allergies, Alzheimer’s disease, bone disease, cancer, chromosomal damage, pregnancy, gastrointestinal damage, heart disease, infertility, kidney disease, Down syndrome, and sterility.

Those opposed to fluoridation for a variety of reasons have had a tendency to use any argument possible to capture the public interest to oppose fluoridation. The arguments range from “being a communist plot” to “causes rusty pipes” in the 1950s and 1960s to cancer, AIDS, and Alzheimer’s disease in the 1970s, 1980s, and 1990s, respectively. A misuse of facts and quoting from studies lacking scientific rigor are often used to support these allegations.23–25 The safety of fluoridation has been time-consuming and costly to document because of the range of allegations made by the opponents, or “antifluoridationists,” over the years. As a result, fluoridation is one of the most well researched public health measures. Concomitantly, the safety of this preventive measure has been relatively easy to document because millions of Americans have for generations lived in communities with naturally fluoridated water. In addition, many communities in the United States and other countries have a fluoride level that is naturally much higher than the recommended level, so that it is much easier to do studies to disprove these false allegations. The safety and effectiveness of water fluoridation as a public health measure is well established for the scientific and health communities; thus most national organizations representing these disciplines, such as the American Medical Association, the American Public Health Association, the American Association of Public Health Dentistry, and the American Dental Association, have endorsed or supported fluoridation (Box 10-2).

Effectiveness.

The effectiveness of fluoridation in preventing dental caries has been well documented.26 Early controlled studies of adjusted fluoridation demonstrated that 50% to 70% of caries in the permanent teeth of children was prevented.27–30 Since 1980, because of the widespread use of fluorides in the United States, the measurable effectiveness of water fluoridation is now approximately 20% to 40%.26 This phenomenon is due, in part, to the fact that many other fluoride-containing products are now available, such as dietary fluoride supplements, rinses, toothpaste, professionally applied treatments, and dilution and diffusion effects, which are described here.

A comprehensive review of fluoridation states that fluoridation prevents caries in primary teeth by 30% to 60% for children 3 to 5 years of age, 20% to 40% for children with a mixed dentition (ages 6 to 12 years), and approximately 15% to 35% for adolescents and adults.18,31 Fluoridation also helps prevent root caries in senior adults by 17% to 35%.31 In countries or communities where there is no widespread use of fluorides, the effectiveness would be expected to be similar to that in early studies conducted in the United States. A recently reported study documented this phenomenon.32

Dilution and Diffusion Effects.

Water fluoridation is as effective now as it was in the past. Because of the widespread use of fluorides in the United States in both fluoridated and nonfluoridated communities, however, the measurable benefits of fluoridation are lower in the United States. This phenomenon is called the dilution effect. Communities without fluoridation also benefit from foods and drinks processed in communities with fluoridation and sold or used in communities without fluoridation. This factor is called the diffusion effect and it also affects the measurable benefits of water fluoridation.26 A recent study showed that in nonfluoridated communities that had a high diffusion effect from fluoridated communities, there is less dental caries.33 Diffusion effects also can occur when individuals who live in communities without fluoridation work or go to school in a community that has optimal fluoridation. In contrast, the effects of the increased use of bottled water and filters for tap water are not known.

Cost.

Of all the measures used to prevent dental caries in the United States, water fluoridation is the most economical and cost-effective. In 1989 the weighted average cost of fluoridation was estimated to be $0.51 per capita per year for the United States, with a range of $0.12 to $5.41, depending on the size of the community and the complexity of the water system.34 In 1999 dollars, this would translate to an average per capita cost of $0.72 per year with a range of $0.17 to $7.62.35 For larger communities the cost of fluoridation is usually less and for smaller communities it is more, as shown here in 1999 dollars:

| Annual Cost per Capita | Community Population |

|---|---|

| $0.84-$7.62 | Less than 10,000 |

| $0.25-$1.05 | 10,000 to 200,000 |

| $0.17-$0.29 | Greater than 200,000 |

| Weighted average: $0.72 |

For approximately 85% of the population in fluoridated communities, the average annual cost per capita was $0.12 to $0.75 in 1989 dollars36 or $0.17 to $1.05 in 1999 dollars. A recent study showed that Medicaid-eligible children who lived in fluoridated communities in Louisiana had approximately 50% lower dental bills than Medicaid-eligible children who lived in nonfluoridated communities.37 For every dollar spent on water fluoridation there is an estimated $25 to $80 savings in treatment costs based on community size, costs, and different study methodologies.38,39 This is an excellent cost-benefit ratio and is the highest for all the caries preventive measures used in the United States.

Practicality.

The concentration of fluoride in a water supply must be monitored on a routine and systematic basis. Thus it is important for water operators to have the appropriate training in fluoridation and to maintain and monitor the concentration of fluoride as recommended.13,40

Antifluoridationists.

Individuals who are opposed to community water fluoridation are termed antifluoridationists. Reasons used for opposing fluoridation include safety, individual rights, government mistrust, home rule, and religious freedom. None of the arguments against fluoridation has any merit based on scientific knowledge and public health experience. Further, none of the arguments has any merit on the basis of state or federal laws. The U.S. Supreme Court has denied a review of fluoridation cases 13 times between 1954 and 1984.41 The primary reasons antifluoridationists have had some limited success are mainly due to an uninformed public, weak or uninformed decision makers, and a weak or poorly organized program to promote and implement fluoridation. A number of significant fluoridation battles have occurred over the years; however, with more than 55 years of health and economic benefits for millions of Americans, the arguments against fluoridation become weaker and weaker. This reality does not mean antifluoridationists have given up or ever will.

Antifluoridationists attempt to appeal to the emotions of the public and elected officials and promote fluoridation as a political issue rather than a public health program. Most communities in the United States make their decisions to fluoridate administratively on the basis of public health expertise. From 1989 to 1994, 337 communities in the United States decided to fluoridate the water supply, and 318, or 94%, were decided by administrative decisions from a city council or commission.42 Of the 32 referenda or public votes that occurred during that time, 19 (61%) supported fluoridation. In fall 2000 there were 23 fluoridation referenda in different communities throughout the United States. Of these, there were 9 (39%) wins for fluoridation and 14 (61%) losses. However, the 9 winning communities had a population of approximately 3.9 million people compared with approximately 366,347 for the losing communities, more than a tenfold difference.43 When the public is forced to vote on a complex public health program such as fluoridation, the antifluoridationists usually use deceptive, misleading, and incorrect information to confuse the public so that they vote for the status quo, to their own detriment. Compounding this problem is the fact that we have failed to educate the American population about how fluorides work and who benefits from their use. Numerous studies have shown that, in general, the U.S. public is not knowledgeable about fluorides and does not know that the use of fluoride is the best approach to caries prevention.44,45 Fluoridation battles still occur in some communities; however, if the political and professional will is present and the public and decision makers are well informed, the implementation of fluoridation will be successful.46–51 For example, in 2000 three major U.S. communities–Clark County (Las Vegas), Nevada; Salt Lake County (Salt Lake City), Utah; and San Antonio, Texas–had public votes in support of fluoridation, after extensive educational efforts in these communities.

Community Support.

The key to achieving fluoridation in most communities is through organized community support, which is the essence of dental public health, defined by the American Board of Dental Public Health as “the science and art of preventing and controlling dental diseases and promoting dental health through organized community efforts.”52 Just as community water fluoridation should be the foundation of any caries prevention program, educating the public is the key to achieving and maintaining community water fluoridation or any other public health measure. Box 10-3 includes basic concepts about fluorides that everyone should know and understand.

BOX 10-3 What Everyone Should Know about Preventing Oral Diseases

A planned educational program for community leaders, organizations, agencies, and institutions is important, beginning with health and human services leadership and then including all other community groups. Once there is widespread community support for fluoridation or any other type of population-based program, it is much easier to implement, support, and sustain. As part of such an educational effort, dentists and physicians also should educate their patients, especially those who are community leaders, about the benefits of fluoridation for the community. It is beyond the scope of this chapter to detail how to organize an educational campaign for fluoridation. Many states and large cities have dental directors who have had experience with implementing and monitoring fluoridation. Further, the dental literature has many articles on fluoridation campaigns that may be helpful.46–51,53–59

National Fluoride Plan.

In 1996 a national fluoride plan to promote oral health in the United States was developed by the U.S. Public Health Service.60 The purpose of this plan was to determine what must be done to reach the water fluoridation or fluoride-related objectives of Healthy People 2000 and to respond to the recommendations of the U.S. Public Health Service report Review of Fluoride: Benefits and Risks.18 The plan was organized into four areas: policy, research, surveillance, and education. A status report for each area was given with recommendations for future strategies of action, which should include the following:

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses