Diseases Affecting the Temporomandibular Joint

After studying this chapter, the student will be able to:

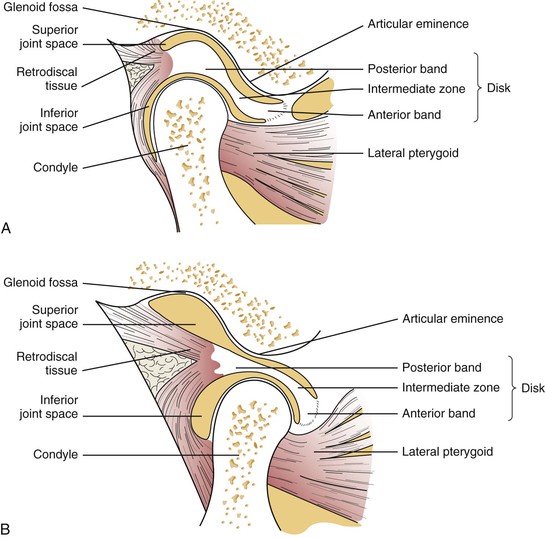

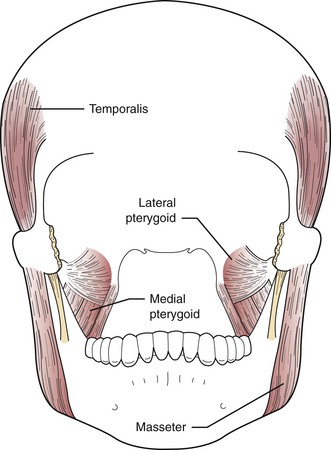

1. Label the following on a diagram of the temporomandibular joint: glenoid fossa of the temporal bone, articular disk, mandibular condyle, joint capsule, and superior belly of the lateral pterygoid muscle.

2. State the function of the muscles of mastication.

3. List at least five causes of orofacial pain not including dental conditions and temporomandibular disorders.

4. State three factors that have been implicated in the cause of temporomandibular disorders and three questions that would be appropriate to ask of a patient suspected of having a temporomandibular disorder.

5. List at least two symptoms that are suggestive of temporomandibular dysfunction.

6. List three imaging techniques useful for evaluating the temporomandibular joint and describe the rationale for each one.

7. List five types of temporomandibular disorders.

8. List and describe the two main categories of treatment of temporomandibular disorders.

9. State the names of one benign tumor and one malignant tumor that may affect the temporomandibular joint area.

Knowledge of the anatomy and function of the temporomandibular joint (TMJ) enables the dental hygienist to understand the diseases that affect the joint. Disorders of the TMJ include myofascial pain and dysfunction (MPD), internal derangements, osteoarthritis, and rheumatoid arthritis (Box 10-1). Benign and malignant tumors can also affect the TMJ.

Anatomy of the Temporomandibular Joint

The TMJ is the articulation between the condyle of the mandible and the glenoid fossa of the temporal bone (Figure 10-1). It is a highly specialized joint that differs from other joints because of the fibrocartilage that covers the bony articulating surfaces, its ginglymoarthrodial (rotational and translational) movement, the fact that its function and overall health are dictated by jaw movement, and its dependence on the contralateral joint. An articular disk is interposed in the space between the temporal bone and the mandible. This disk divides the space into an upper compartment (superior joint space) and a lower compartment (inferior joint space) (Figure 10-1).

Translational movements occur in the upper compartment, whereas the lower compartment functions primarily as the hinge or rotational component. The superior and inferior spaces contain synovial fluid, which is produced by the synovial membrane that lines the joint. The synovial fluid provides nourishment and lubrication of the avascular structures. The articular disk is attached to the lateral and medial aspects of the condyle, to the superior belly of the lateral pterygoid muscle, and to the joint capsule (Figure 10-1). The articular disk and the bony surfaces are avascular (i.e., they do not contain blood vessels) and devoid of nerve fibers. The joint is further surrounded and protected by the fibrous connective tissue joint capsule. The primary innervation of the TMJ capsule and disk attachments is from the auriculotemporal nerve with secondary innervation from the deep temporal and masseteric nerves. The function of the disk is to separate the forces resulting from rotation and translation, absorb shock, improve the fit between bony surfaces, protect the edges of the articulating surfaces, distribute weight over a larger area, and spread the lubricating synovial fluid.

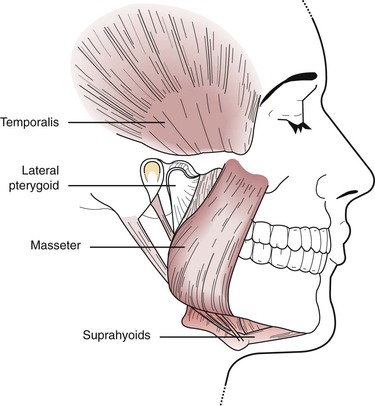

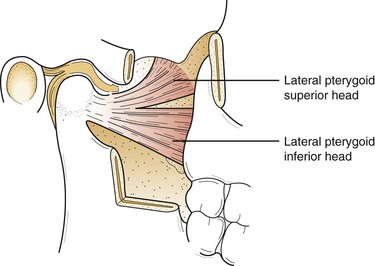

Understanding the location and action of the muscles of mastication is important in the evaluation of disorders affecting the TMJ. Palpation of these muscles during a clinical evaluation is done to determine whether muscle spasm or dysfunctional muscle activity is occurring. The muscles of mastication comprise major muscles about the facial region that govern the movement of the mandible. They include the masseter, temporalis, medial pterygoid, lateral pterygoid, anterior digastric, and mylohyoid (suprahyoids) (Figures 10-2 to 10-4). The function of these muscles is to create the mandibular envelope of motion. Three of these muscles, the masseter, medial pterygoid, and temporalis, are elevator muscles that, when activated, close the mandible. The opening, or depressor, function is accomplished mainly by the lateral pterygoid muscle with some help from the anterior digastric muscle. Studies have shown that the two components of the lateral pterygoid muscle are active at different times in the functioning of the mandible (Figure 10-4). The superior portion of the muscle seats the articular disk on the eminence of the articulating surface. The inferior belly is attached to the mandibular condyle and functions during mouth opening.

Normal Joint Function

In normal joint function the jaw begins at a rest position of maximal occlusal contact. In this position the mandibular condyle rests within the glenoid fossa, with the articular disk situated between the condyle, roof of the glenoid fossa, and articular eminence (see Figure 10-1, A and B). The first phase of opening is characterized by rotational (hinge) movement of the condyle, followed by anterior translation (sliding movement) to approximately the anterior peak of the articular eminence. During translation the disk assumes a more posterior position in relation to the condyle. The inferior and superior joint spaces assume different configurations during each of these movements.

Temporomandibular Disorders

Epidemiology

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses

)

) )

) )

) )

) )

) )

) )

)

)

) )

) )

) )

) )

)