Cysts and odontogenic tumours

10.1 General features

Classification of cysts

Cysts can be classified on the basis of:

Box 10.1 lists the cysts found in the orofacial region using these groups.

Other cysts

10.2 Examination

General clinical features

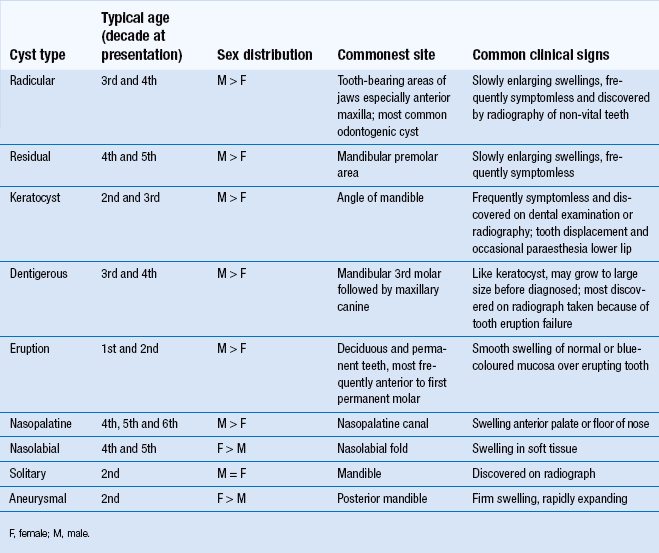

Cysts may be detected because of clinical symptoms or signs (Table 10.1). Occasionally an asymptomatic cyst may be discovered on a radiograph taken for another purpose. Symptoms may include:

The most important clinical sign is expansion of bone. In some instances, this may result in an eggshell-like layer of periosteal new bone overlying the cyst (Fig. 10.2). This can break on palpation, giving rise to the clinical sign of ‘eggshell cracking’. If the cyst lies within soft tissue or has perforated the overlying bone, then the sign of fluctuance may be elicited by palpating with fingertips on each side of the swelling in two positions at right angles to each other.

Radiological examination: general principles

As a basic principle, radiological examination should commence with intraoral films of the affected region; for small cystic lesions, intraoral films may be all that is needed for diagnosis, while for all cysts the fine detail of intraoral radiography will help to clarify the relationship between lesion and teeth. For larger lesions, more extensive radiography is appropriate. Selection of films should take account of the value of having two views with differing perspectives (preferably at right angles to each other; Fig. 10.2).

Radiological signs

Margins: Peripheral cortication (radio-opaque margin) is usual except in solitary bone cysts. ‘Scalloped’ margins are seen in larger lesions, particularly keratocysts. Infection of a cyst tends to cause loss of the well-defined margin.

Shape: Most cysts grow by hydrostatic mechanisms, resulting in the round shape. Odontogenic keratocysts and solitary bone cysts do not grow in this manner and have a tendency to grow through the medullary bone rather than to expand the jaw.

Locularity: True locularity (multiple cavities) is seen occasionally in odontogenic keratocysts. However, larger cysts of most types may have a multilocular appearance because of ridges in the bony wall.

Effects upon adjacent structures: Where a lesion abuts another structure, such as a tooth or the inferior dental canal, it may cause displacement. Roots of teeth may be resorbed. When a cyst reaches a certain size, the cortex of the bone often becomes thinned and expanded. In posterior maxillary lesions, the antral floor may be raised. Perforation of the cortical plates may be recognised as a localised area of greater radiolucency overlying the lesion.

10.3 Specific cysts

Radicular cyst

A well-defined, round or ovoid radiolucency is associated with the root apex or, less commonly in the lateral position, of a heavily restored or grossly carious tooth. A corticated margin is continuous with the lamina dura of the root of the affected tooth. The appearances are similar to those of an apical granuloma, but lesions with a diameter exceeding 10 mm are more likely to be cystic (Fig. 10.3).

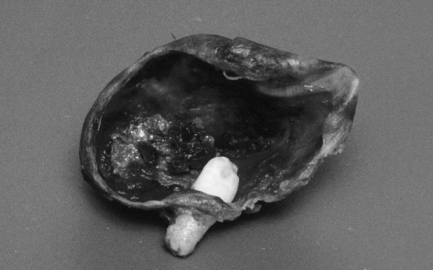

Pathology

The cyst lumen is lined by a layer of simple, non-keratinising, squamous epithelium of variable thickness, which may display areas of discontinuity where it is replaced by granulation tissue or mural cholesterol nodules. Arcades and strands of epithelium may extend into the cyst capsule, which is composed of granulation tissue infiltrated by a mixture of acute and chronic inflammatory cells. This infiltrate reduces in intensity as the more peripheral areas of the cyst capsule are approached, where mature fibrous tissue replaces the granulation tissue (Fig. 10.4).

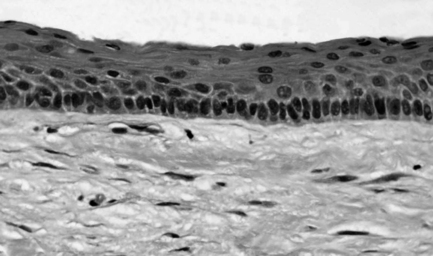

Fig. 10.4 Photomicrograph of a radicular cyst.

Residual cyst

Odontogenic keratocyst

There is a well-defined radiolucency in odontogenic keratocysts, often with densely corticated margins. The outline may be ‘scalloped’ in shape. Occasionally, there is a multilocular appearance. Expansion is typically limited, with a propensity to grow along the medullary cavity (Fig. 10.5). This cyst was reclassified by The World Health Organization (WHO) in 2005 as keratocystic odontogenic tumour (KCOT) but the evidence for this reclassification is weak and it is likely to revert to odontogenic keratocyst at the next WHO edition.

Fig. 10.5 Odontogenic keratocyst.

The lesion is very well defined with a corticated margin. The wisdom tooth appears displaced, as does the inferior dental canal, visible at the inferior and posterior aspects of the cyst. The shape is not round or ovoid, but rather irregular with a separate locule below the crown of the wisdom tooth.

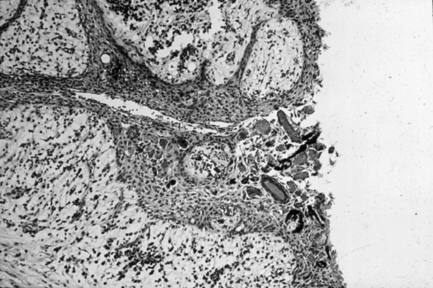

Pathology

The cyst is lined by a continuous layer of stratified squamous epithelium of even thickness (5–10 cells), the surface of which is corrugated. The basal-cell layer is well defined, being composed of cuboidal or columnar cells that display palisading. This epithelium is most commonly parakeratinising, although orthokeratosis may be observed. The lumen of the cyst is filled with shed squames. The cyst capsule is composed of rather delicate fibrous tissue and is, classically, free from inflammation (Fig. 10.6). However, should the cyst become infected then an inflammatory infiltrate may be seen and the characteristic features of the epithelial lining will be lost.

Fig. 10.6 Photomicrograph of a keratocyst.

Dentigerous cyst

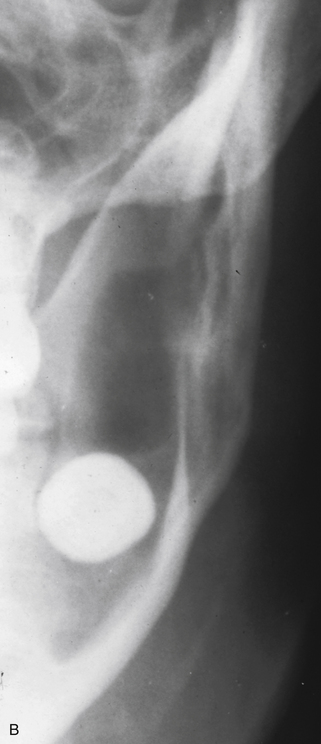

In dentigerous cysts, there is a pericoronal radiolucency greater than 3–4 mm in width that is suggestive of cyst formation in a dental follicle. The well-defined, corticated radiolucency is associated with the crown of an unerupted tooth. Classically the associated crown of the tooth lies centrally within the cyst, but lateral types occur (Fig. 10.7).

Pathology

The defining feature of a dentigerous cyst is the site of attachment of the cyst to the involved tooth. This must be at the level of the amelocemental junction. The lining of the cyst is composed of a thin layer of epithelium, either cuboidal or squamous in nature, some 2–5 cells thick (Fig. 10.8). This lining is of even thickness and may include mucous cells along with focal areas of keratinisation of the superficial epithelial cells. The cyst capsule is, classically, free from inflammation. However, in common with the odontogenic keratocyst, the normal features of the epithelial lining may be distorted when an inflammatory infiltrate is present.

Eruption cyst

Nasopalatine cyst

The nasopalatine cyst appears as a well-defined, round radiolucency in the midline of the anterior maxilla (Fig. 10.9). Sometimes it appears to be ‘heart-shaped’ because of superimposition of the anterior nasal spine. Radiological assessment should include examination of the lamina dura of the central incisors (to exclude a radicular cyst) and assessment of size (the nasopalatine foramen may reach a width of as much as 10 mm).

Solitary bone cyst

The solitary bone cyst appears as a well-defined but non-corticated radiolucency. Typically, it has little effect on adjacent structures and ‘arches’ up between the roots of teeth (Fig. 10.10). The inferior dental canal may not be displaced, but the cortical margins of the canal may be lost where it overlies the lesion. Expansion is rare.

Fig. 10.10 Solitary bone cyst.

There is a large radiolucency in the body of the mandible that arches up between the roots of the teeth, which appear otherwise unaffected. The lower border cortex is very thin. The inferior dental canal is not displaced but appears to stop abruptly at the posterior end of the lesion.

10.4 Surgical management of cysts

Surgical management of cysts generally implies enucleation, but occasionally marsupialisation is the technique of choice. Some small radicular cysts do not require surgery and regress once the root canal of the associated tooth has been effectively cleaned and filled. Antibiotic therapy may be required if a cyst has become infected. Aspiration of fluid from a pathological cavity may be helpful in confirming the presence of cyst rather than maxillary sinus (air) or tumour (solid). Biochemical analysis of the aspirate indicating protein content of less than 40 g/l and cytology showing parakeratinised squames suggests an odontogenic keratocyst.

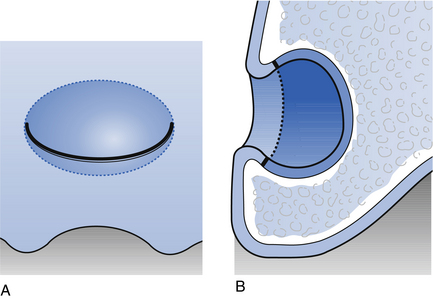

Marsupialisation

Marsupialisation is a simple operation that may be performed under local anaesthesia in which a window is cut and removed from the cyst lining. This allows decompression of the cyst, which then slowly heals by bone deposition in the base of the cavity. However, this technique permits histopathological examination of only a small and possibly non-representative sample of tissue. Primary closure is not undertaken but rather the cyst lining is sutured to the oral mucosa to keep the cavity open (Fig. 10.11). The cavity must be filled with a dressing such as BIPP, which must be frequently replaced, to prevent food debris trapping during the many months the cavity may take to heal. Alternatively, an extension may be added to a denture to protect the cavity, which becomes reduced in size as the cavity heals.

Fig. 10.11 Marsupialisation.

(A) An incision is made over a large cystic lesion in the maxillary alveolus. (B) The flap is sutured to the margins of the cyst lining following excision of a window of tissue for pathological examination.

Marsupialisation is advocated when the cyst is so large that />

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses