Overview of Preventive and Restorative Materials

Although many properties of biomaterials can be grouped into one of the broadest categories, i.e., physical properties, this book has been designed to separate these properties into subcategories that allow a clearer visualization of the variables that are most likely to influence the success or failure of preventive and restorative dental materials. Chemical properties generally comprise the behavior of materials in a chemical environment with or without any other external influences. Mechanical properties are related primarily to the behavior of materials in response to externally applied forces or pressures. Of course, in a clinical environment, the behavior of dental materials may be dependent on several variables simultaneously, but a general understanding of a material’s performance will be controlled by our ability to differentiate primary from secondary factors or properties. Lists of the most relevant chemical, manufacturing, mechanical, optical, and thermal properties are presented below. Separate chapters are devoted to more detailed descriptions: Chapter 3, “Chemical and Physical Properties of Solids,” and Chapter 4, “Mechanical Properties of Solids.” Because of the dramatic increase in the use of CAD-CAM technology, a category of processing or manufacturing properties has been introduced in this chapter.

General Categories of Biomaterials Properties

Chemical properties and parameters

Properties of importance in manufacturing or finishing processes

Melting temperature or melting temperature range

Flowability under hot-isostatic-pressing (HIP) temperature and pressure conditions

Optical properties and parameters

Physical Properties

A physical property is any measurable parameter that describes the state of a physical system. The changes in the physical properties of a biomaterial can serve to describe the changes or transformations of the material when it has been subjected to external influences such as force, pressure, temperature, or light. Because these properties may include other properties listed above, a more detailed description of their characteristics is presented in Chapter 3, “Chemical and Physical Properties of Solids.” In contrast to physical properties, chemical properties define the ways in which a material behaves during a chemical reaction or in a chemical environment.

What Are Dental Materials?

Dental materials may be classified as preventive materials, restorative materials, or auxiliary materials. Preventive dental materials include pit and fissure sealants; sealing agents that prevent leakage; materials used primarily for their antibacterial effects; and liners, bases, cements, and restorative materials such as compomer, hybrid ionomer, and glass ionomer cement that are used primarily because they release fluoride or other therapeutic agents to prevent or inhibit the progression of tooth decay (dental caries). Table 1-1 summarizes the types of preventive and restorative materials, their applications, and their potential durability. In some cases a preventive material may also serve as a restorative material that may be used for a short-term application (up to several months), for moderately long time periods (1 to 4 years), or for longer periods (5 years or more). Dental restoratives that have little or no therapeutic benefit may also be used for short-term (temporary) use, or they may be indicated for applications requiring moderate or long-term durability. For example, restorative materials that do not contain fluoride can be used for patients who are at a low risk for caries.

TABLE 1-1

Comparative Applications and Durability of Preventive and Restorative Dental Materials

| Material Type | Applications of Products | Potential Preventive Benefits | Durability |

| Resin adhesive | A | F (certain products) | M |

| Resin sealant | S | S | M |

| Resin cement | L | F (certain products) | M |

| Compomer | B, L, R | F | M |

| Hybrid ionomer | B, L, R | F | M |

| Glass ionomer (GI) | A, B, L, R, S | F, S | L, M |

| Metal-modified GI | R | F | L, M |

| Zinc oxide–eugenol | B, L, T | – – – | L, M |

| Zinc phosphate | B, L | – – – | M |

| Zinc polycarboxylate | B, L | – – – | M |

| Zinc silicophosphate | B, L | F | M |

| Resin composite | R | F (certain products) | H |

| Dental amalgam | R | – – – | H |

| Ceramic | R | – – – | H |

| Metal-ceramic | R | – – – | H |

| Metal/-resin | R | – – – | M, H |

| Temporary acrylic resin | T | – – – | L |

| Denture acrylic | R | – – – | H |

| Cast metal | R | – – – | H |

| Wrought metal | R | – – – | H |

Potential preventive benefit: F, fluoride-releasing material; S, sealing agent.

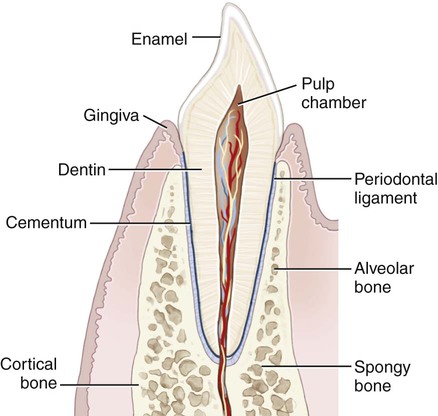

The overriding goal of dentistry is to maintain or improve the quality of life of the dental patient. This goal can be met by preventing disease, relieving pain, improving the efficiency of mastication, enhancing speech, and improving appearance. Because many of these objectives require the replacement or alteration of tooth structure, the main challenges for centuries have been the development and selection of biocompatible, long-lasting, direct-filling tooth restoratives, and indirectly processed prosthetic materials that can withstand the adverse conditions of the oral environment. Figure 1-1 is a schematic cross-section of a natural tooth and supporting bone and soft tissue. Under healthy conditions, the part of the tooth that extends out of adjacent gingival tissue is called the clinical crown; that below the gingiva is called the tooth root. The crown of a tooth is covered by enamel. The root is covered by cementum, which surrounds dentin and soft tissue within one or more root canals.

Historical Use of Restorative Materials

Although inscriptions on Egyptian tombstones indicate that tooth doctors were considered to be medical specialists, they are not known to have performed restorative dentistry. However, some teeth found in Egyptian mummies were either transplanted human teeth or tooth forms made of ivory. The earliest documented evidence of tooth implant materials is attributed to the Etruscans as early as 700 B.C. (Figure 1-2). Around 600 A.D. the Mayans used implants consisting of seashell segments that were placed in anterior tooth sockets. Hammered gold inlays and stone or mineral inlays were placed for esthetic purposes or traditional ornamentation by the Mayans and later the Aztecs (Figure 1-3). The Incas performed tooth mutilations using hammered gold, but the material was not placed for decorative purposes.

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses