Introduction to Preliminary Diagnosis of Oral Lesions

After studying this chapter, the student will be able to:

1. Define each of the terms in the vocabulary list for this chapter.

2. List and define the eight diagnostic categories that contribute to the diagnostic process.

3. Name a diagnostic category and give an example of a lesion, anomaly, or condition for which this category greatly contributes to the diagnosis.

4. Describe the clinical appearance of Fordyce granules (spots), torus palatinus, mandibular tori, and lingual varicosities and identify them in the clinical setting or on a clinical photograph.

5. Describe the radiographic appearance and historical data (including the age, sex, and race of the patient) that are relevant to periapical cemento-osseous dysplasia (cementoma).

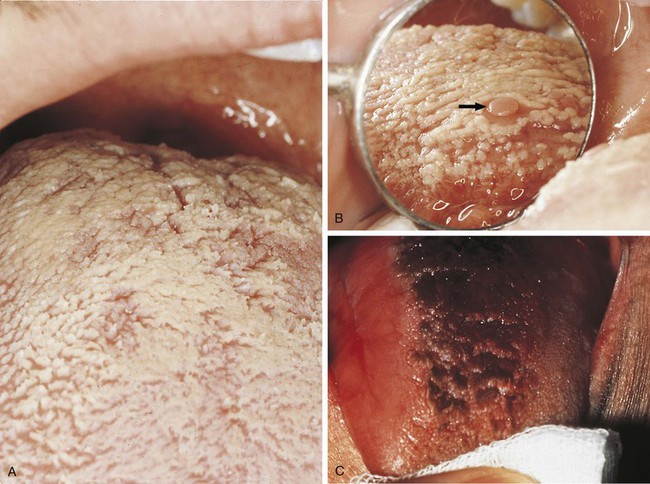

6. Define “variant of normal” and give three examples of these lesions involving the tongue.

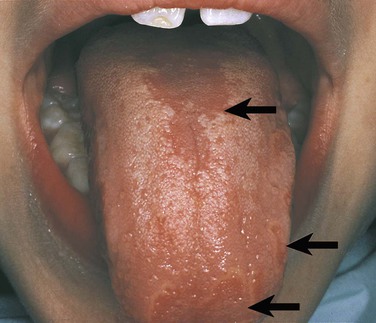

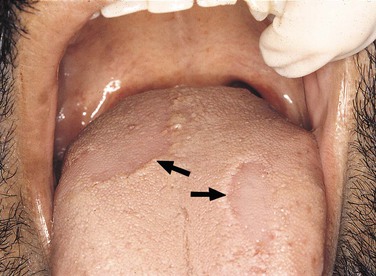

7. List and describe the clinical characteristics and identify a clinical picture of median rhomboid glossitis, geographic tongue, ectopic geographic tongue, fissured tongue, and hairy tongue.

8. Describe the clinical and histologic differences between leukoedema and linea alba.

9. Define leukoplakia and erythroplakia.

10. Discuss the two risk types of human papillomavirus covered in this chapter.

(adjective, lobulated) A segment or lobe that is a part of the whole; these lobes sometimes appear fused together (Figure 1-1).

Describing the base of a lesion that is flat or broad instead of stemlike (Figure 1-3).

One-thousandth of a meter (a meter is equivalent to 39.3 inches); the periodontal probe is of great assistance in documenting the size or diameter of a lesion that can be measured in millimeters (general terms such as small, medium, or large are sometimes used, but these terms are not as specific) (Figure 1-5).

Radiographic Terms Used to Describe Lesions in Bone

The process by which parts of a whole join together, or fuse, to make one.

Describes a lesion with borders that are not well defined, making it impossible to detect the exact parameters of the lesion; this may make treatment more difficult and, depending on the biopsy results, more radical (Figure 1-6).

Describes a lesion that extends beyond the confines of one distinct area and is defined as many lobes or parts that are somewhat fused together, making up the entire lesion; a multilocular radiolucency is sometimes described as resembling soap bubbles; an odontogenic keratocyst often presents as a multilocular, radiolucent lesion (Figure 1-7).

Describes the black or dark areas on a radiograph; radiant energy can pass through these structures; less dense tissue such as the pulp is seen as a radiolucent structure (Figure 1-8).

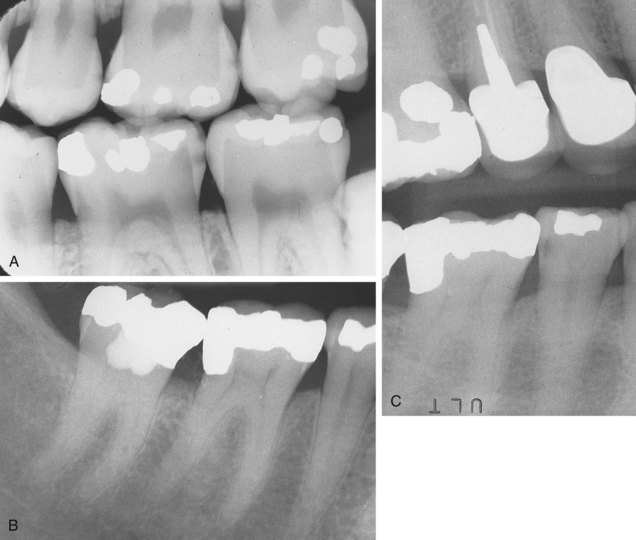

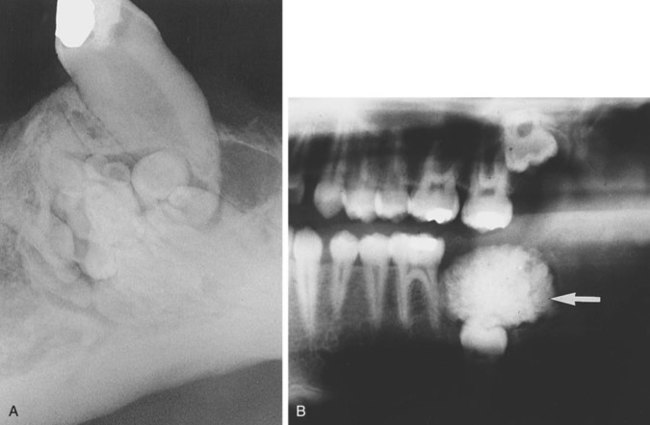

Terms used to describe a mixture of light and dark areas within a lesion, usually denoting a stage in the development of the lesion; for example, in a stage I periapical cemento-osseous dysplasia (cementoma) (Figure 1-9, A), the lesion is radiolucent; in stage II it is radiolucent and radiopaque (Figure 1-9, B).

Describes the light or white area on a radiograph that results from the inability of radiant energy to pass through the structure; the denser the structure, the lighter or whiter it appears on the radiograph; this is illustrated in Figure 1-10.

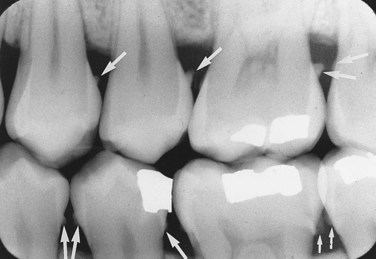

Observed radiographically when the apex of the tooth appears shortened or blunted and irregularly shaped; occurs as a response to stimuli, which can include a cyst, tumor, or trauma; Figure 1-11 illustrates resorption of the roots as a result of a rapid orthodontic procedure (see Figure 1-27); external resorption arises from tissues outside the tooth such as the periodontal ligament, whereas internal resorption is triggered by pulpal tissue reaction from within the tooth; in the latter the pulpal area can be seen as a diffuse radiolucency beyond the confines of the normal pulp area.

A radiolucent lesion that extends between the roots, as seen in a traumatic bone cyst; this lesion appears to extend up the periodontal ligament (Figure 1-12).

The Diagnostic Process

Making A Diagnosis

Clinical Diagnosis

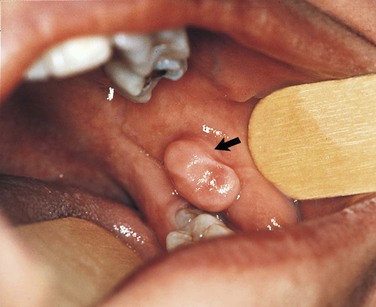

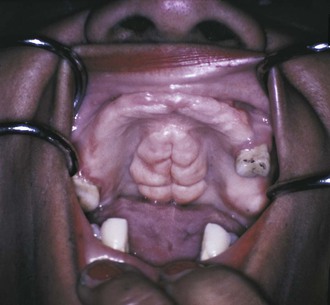

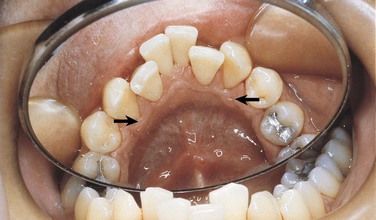

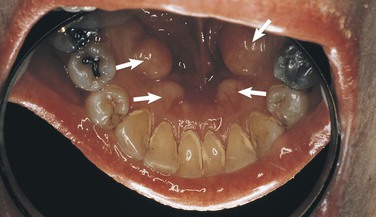

Clinical diagnosis suggests that the strength of the diagnosis comes from the clinical appearance of the lesion. By observing the area in a well-illuminated clinical setting and palpating it if necessary, the clinician can establish a diagnosis for some lesions on the basis of color, shape, location, and history of the lesion. When a diagnosis can be made on the basis of these unique clinical features, biopsy or surgical intervention is not necessary. Examples of lesions that can be clinically diagnosed are Fordyce granules (Figure 1-15), torus palatinus (Figure 1-16), mandibular tori (Figure 1-17), melanin pigmentation (Figure 1-18), retrocuspid papillae (Figure 1-19), and lingual varicosities (see Figure 1-52). These lesions are described later in this chapter.

Other benign conditions of unknown cause that are recognized by their distinct clinical appearance include fissured tongue (Figure 1-20), median rhomboid glossitis (Figure 1-21), geographic tongue (Figure 1-22), and hairy tongue (Figure 1-23). These conditions are also discussed later in this chapter.

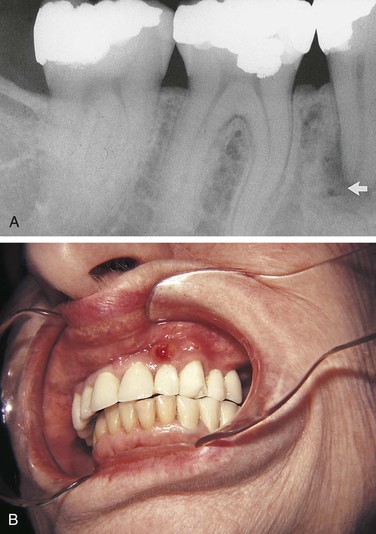

Sometimes the diagnostic process requires historical information in addition to the clinical findings. For example, an amalgam tattoo (focal argyrosis) can be observed as a blue-to-gray patch on the gingiva or mucosa where an amalgam restoration is or has been located (Figure 1-24). Although this condition is usually easily observed and a clinical diagnosis made, any history involving the area can still be very helpful in confirming the clinical impression. The patient in Figure 1-24 had root canal therapy and a retrograde amalgam on a deciduous tooth. The amalgam tattoo is observed in the apical area of the permanent central incisor; no evidence of an amalgam restoration exists in the entire anterior area. The history helped confirm the clinical diagnosis.

Radiographic Diagnosis

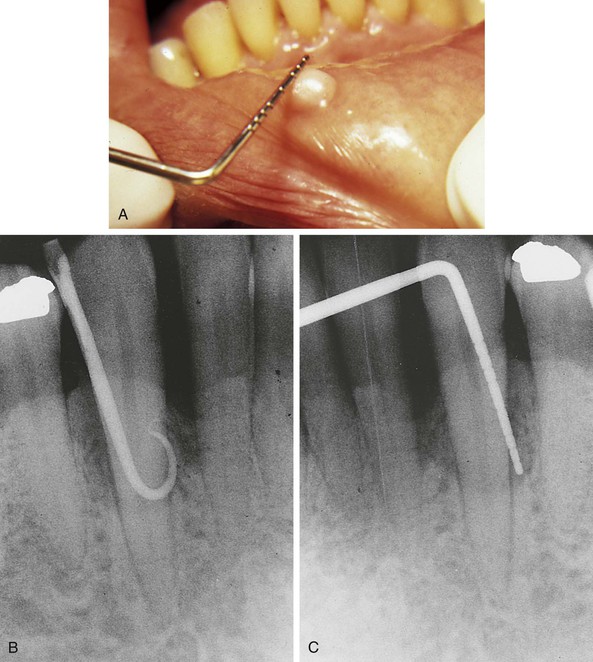

In a radiographic diagnosis the radiograph provides sufficient information to establish the diagnosis. Although additional clinical and historical information may contribute, the diagnosis is obtained from the radiograph. Conditions for which the radiograph provides the most significant information include periapical pathosis (Figure 1-25), internal resorption (Figure 1-26), external resorption (Figure 1-27), heavy interproximal calculus (Figure 1-28), dental caries (Figure 1-29), compound odontoma (Figure 1-30), complex odontoma (Figure 1-31), supernumerary teeth (Figure 1-32), impacted or unerupted teeth (Figure 1-33), and calcified pulp (Figure 1-34). Normal anatomic landmarks are also easily observed radiographically. In some cases the radiograph may show very distinct and well-defined structures such as the nutrient canals seen in Figure 1-35, A and B and the mixed dentition seen in Figure 1-35, C. Unusual radiographic findings are illustrated in Figure 1-36.

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses