1

1

General Assessment

Introduction

The overall management of a patient with facial deformity requiring orthognathic surgery is both an art and a science. The management must be based on a team approach. Whilst the team may vary according to local circumstances, the optimum would consist of an orthodontist, an oral and maxillofacial surgeon, a liaison psychiatrist or clinical psychologist, a specialist in restorative dentistry, supported by a maxillofacial technician. A speech therapist is essential for cleft cases and plastic surgery expertise should also be available on an individual patient basis. Whilst a patient may be referred to any of the above specialists, it is important that all patients follow an agreed care pathway to ensure patient satisfaction with the outcome. Unfortunately the patient’s personal concerns may be overlooked and it is imperative that as part of the initial consultation, patients are encouraged to state precisely what specific aspects of their facial features and or dentition they would like corrected, for what reason and the length of time that they have sought treatment. Research has shown that clinicians and the general public differ in their perception of an ideal face. Whilst the patient can be guided to what constitutes an ideal facial appearance, it is vital that the clinician does not lose sight of the patient’s underlying concerns. The motivation behind the request for treatment is also very important and special consideration is required when marked psychological factors appear to influence both the diagnosis and the treatment.

Combined orthodontic/surgical treatment goals are:

- Improve facial aesthetics

- Improve dental aesthetics

- A functional, balanced and stable occlusion

- A satisfied patient.

The management protocol for facial deformity should comprise the:

- History

- Clinical examination

- Investigations

- Initial diagnosis

- Treatment plan

- Presurgical orthodontics

- Final treatment plan

- Surgery

- Postsurgical orthodontics

- When appropriate, restorative dentistry, psychological intervention or support and speech therapy will be required.

History

The purpose of the history is to identify the patient’s orofacial problems and their cause. This may be a family trait, congenital deformity, or trauma in infancy or adolescence. It is useful to ask the patient to draw up a problem list in order of priority of the specific features they wish to have corrected and for the clinician to note where the drive for treatment has arisen. For example, a patient may complain of having a prominent chin, which they have noticed ever since adolescence and for which they have frequently requested treatment through the general dental practitioner. This differs from the sudden desire to change minimal deformity as a response to a personal crisis. The long term success in terms of patient satisfaction is far better when driven by the patient than that of a patient seeking surgery driven by a parent, partner or close relative. The overall treatment goals must be to improve facial and dental aesthetics, and to provide a functional, balanced and stable occlusion but with the underlying premise that these satisfy the patient’s reasonable wishes.

The Medical History

Most orthognathic patients are young and fit to undergo a general anaesthetic and prolonged surgery. Occasional disorders, which require specific attention include:

i) haemophilia or similar clotting disorders which require pre-and intraoperative correction

ii) acromegaly patients may be a cardiomyopathy risk

iii) antibiotic or analgesic idiosyncrasy or allergy

iv) rheumatic or congenital heart valve lesions

v) obstructive sleep apnoea should warrant a sleep study and specific assessment.

Body Dysmorphic Disorder (Formerly Dysmorphophobia)

A small but significant proportion of patients may present with varying degrees of concern about one or more aspects of their facial appearance without appropriate clinical signs. This may be a manifestation of a psychiatric disturbance now called Body Dysmorphic Disorder (formerly dysmorphophobia). This condition will create problems in surgical management as the patient is often dissatisfied with the final result. The condition raises the conflict as to whether one does,

i) what the patient wants

ii) what the patient needs

iii) or nothing.

It is therefore worth considering in some detail. See Chapter 6.

Evaluation of the Patient

Patient Evaluation

- Clinical examination

- Radiographic examination

- Analysis of study models

- Psychological examination where appropriate.

Introduction

The full examination must include the simultaneous scrutiny of the patient, radiographs, cephalometry and study casts. The evaluation of the orthognathic patient should begin with a systematic examination of the patient’s facial features from both the frontal perspective (vertical proportions) and the lateral profile (horizontal relations). It is important to consider the vertical facial proportions and their balance in relation to the patient’s general build, and personality. Examples of patients who may not need surgery are: (i) a young female patient who possesses a vivacious and extrovert personality suited to a mild Class II malocclusion accompanied by a broad smile and marked incisor exposure and (ii) similarly, a well-built male may be suited to a mild Class III malocclusion with a minor degree of mandibular prognathism. It is also important to take into consideration the overall facial shape, as clearly there is extreme variation from a square shaped facial appearance to one of a long ovoid appearance. In the former case this may fit in well with a shorter stature whereas a longer face may be more suited to a tall individual. At the moment these decisions are based on experience and intuition.

Clinical Examination

The clinical examination should be undertaken with the patient comfortably seated with the Frankfort plane horizontal. Not only is it easy to visualise a line running from the inferior orbital margin to the upper end of the tragal cartilage, but this can be readily compared with the same horizontal plane on the lateral skull radiograph (cephalogram) and photographs.

Frontal Assessment

There are several important facial features to note. These include:

a) The facial proportions

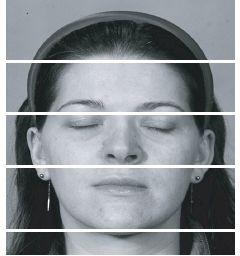

The useful classic guide is to consider the face as having three equal vertical components (Figure 1.1): The distance from the hairline to the soft tissue bridge of the nose; from the soft tissue bridge of the nose to the alar base and from the alar base to the chin. It is also important to determine whether or not there is a relative excess or deficiency in the vertical height of either the maxillary or mandibular thirds.

b) The alar base width

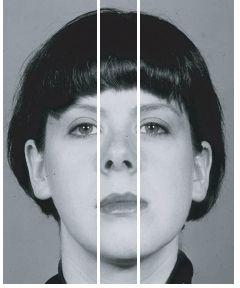

Traditionally in a westernised population it is accepted that the alar base width, as measured from the lateral aspects of the alar cartilages of the nose, should be approximately equal to the intercanthal distance as measured between the inner canthi of the eyes (Figure 1.2). This measurement has importance when planning a maxillary impaction.

Figure 1.1 The superficial aesthetic proportions of the face can be divided into equal thirds. However the underlying cephalometric proportions of the upper to the lower facial height are 45:55 (see Figure 2.3).

Figure 1.2 The alar base width should approximate the inner intercanthal distance.

c) Incisor exposure (the lip — incisor relationship)

For a patient with an average upper lip length of 20-25 mm, the standard exposure for orthognathic planning of the upper labial segment with the lips parted at rest should be 2-4mm of the incisor crown. On smiling, the exposure should increase to the level of the gingival margin of the upper labial segment. This assessment is crucial when planning the ultimate vertical height of the mid face. Quite clearly the amount of incisor exposure should be inversely proportional to the length of the upper lip. (Figure 1.3). Where the upper lip length is very short then the patient would expect to show more of the upper incisors. Any attempt to reduce the incisor exposure in relation to a short upper lip will lead to an unaesthetic reduced middle face height. Similarly, with a long upper lip, the patient would be expected to show less or no upper incisor, both at rest and during facial animation. The lip incisor measurement should be done with the face at rest. Animation especially smiling will enhance the face and make planning difficult.

The harmony between the components of the lower third of the face is also important, in that the subnasale to the upper lip vermillion border should be a third of the total (i.e. half of the lower lip vermillion border to the soft tissue menton). In those cases where the lower third of the face appears overclosed, it is wise to re-evaluate both the upper lip length and the incisor exposure w/>

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses