Oral health for the older adult patient is vital for function, comfort, and communication and is a critical component of overall health. Oral diseases such as dental caries, periodontal disease, and oral cancer may lead to pain, functional limitations, and decreased quality of life. Optimal oral health outcomes are often owing to effective interprofessional collaboration between and among health care providers, in conjunction with patient family members and caregivers. This article highlights 2 cases illustrating how interprofessional team dynamics can affect patient outcomes.

Key points

- •

Most professions related to health care and their associated specialties engage in successful collaborations.

- •

Functional and/or cognitive impairments in older adult patients may necessitate identifying family members and caregivers to help the patient maintain optimal oral health.

- •

Better patient outcomes for older adults result from successful interprofessional collaboration, in conjunction with the support of the patient’s family and caregivers.

- •

Communicating frequently with other team members helps to ensure optimal oral health outcomes over the short and long term.

Introduction

Traditionally, dental and medical education and practice take place separately, with little to no interaction between dentists and physicians during training or later in practice. There is an increased emphasis in recent years to increase interprofessional dental and medical education; the anticipated benefits include collaborative practices that lead to improved patient outcomes. Many older adults who are no longer able to access traditional dental office settings owing to cognitive and/or physical impairment(s) receive dental treatment in nondental settings. Meaningful patient outcomes measures, such as stabilization of weight loss and increased ability to socialize and enjoy food, is observed in some of these patients. With the rapid increase of older adults aged 65 years and over in the United States today, future directions for dental research could include validating outcome measures and assessing increased quality of life after dental treatment in frail older adults in the context of interprofessional collaborative practice.

The older adult population is expanding rapidly and life expectancy is increasing. Many dental patients are older than in the past and thanks to advances in modern dentistry and prevention, the retention of natural dentition into old age is increasing. With advancing age, there may be impairment of cognitive and physical capacities, leading to less than optimal oral hygiene resulting in dental disease. According to Healthy People 2020 , vulnerable populations, including the elderly, suffer disproportionately from dental diseases and often lack access to preventive treatments and dental care. The US Department of Health and Human Services–funded training programs in geriatrics for physicians and dentists educate clinicians together to care for frail older adults’ medical and dental needs (See Joskow RW: Integrating Oral Health and Primary Care: Federal Initiatives to Drive Systems Change , in this issue).

Older adult patients with complex and interrelated medical and dental conditions benefit from well-coordinated health care from a wide range of health care advocates. Multiple medical comorbidities, along with cognitive and physical impairments, may have a negative impact on oral health. Coordinating care between medical and dental providers can be challenging owing to the traditional separation of medical and dental education and practice sites.

A new interprofessional education initiative model between dental and medical students at Boston University is preparing dental and medical students to communicate with each other and work together to provide comprehensive and coordinated care for their patients. Previous research has shown that students trained with an interprofessional approach to education are more likely to become collaborative team members. These students are more likely to show respect and positive attitudes toward each other on future interprofessional teams and work together to improve patient outcomes. The Boston University model of interprofessional education includes a didactic module on oral and systemic health for older adults and hands on experience of intraoral screenings for medical students taught by dental students.

This article uses 2 patient case studies to help illustrate interprofessional collaborative practice. The first is an example of a successful dental–medical collaboration and a second case is one with an unsuccessful oral health outcome. In the future, more interprofessional training opportunities for students in dental and medical schools may lead to better interprofessional clinician communication and increased instances of successful patient clinical outcomes.

Introduction

Traditionally, dental and medical education and practice take place separately, with little to no interaction between dentists and physicians during training or later in practice. There is an increased emphasis in recent years to increase interprofessional dental and medical education; the anticipated benefits include collaborative practices that lead to improved patient outcomes. Many older adults who are no longer able to access traditional dental office settings owing to cognitive and/or physical impairment(s) receive dental treatment in nondental settings. Meaningful patient outcomes measures, such as stabilization of weight loss and increased ability to socialize and enjoy food, is observed in some of these patients. With the rapid increase of older adults aged 65 years and over in the United States today, future directions for dental research could include validating outcome measures and assessing increased quality of life after dental treatment in frail older adults in the context of interprofessional collaborative practice.

The older adult population is expanding rapidly and life expectancy is increasing. Many dental patients are older than in the past and thanks to advances in modern dentistry and prevention, the retention of natural dentition into old age is increasing. With advancing age, there may be impairment of cognitive and physical capacities, leading to less than optimal oral hygiene resulting in dental disease. According to Healthy People 2020 , vulnerable populations, including the elderly, suffer disproportionately from dental diseases and often lack access to preventive treatments and dental care. The US Department of Health and Human Services–funded training programs in geriatrics for physicians and dentists educate clinicians together to care for frail older adults’ medical and dental needs (See Joskow RW: Integrating Oral Health and Primary Care: Federal Initiatives to Drive Systems Change , in this issue).

Older adult patients with complex and interrelated medical and dental conditions benefit from well-coordinated health care from a wide range of health care advocates. Multiple medical comorbidities, along with cognitive and physical impairments, may have a negative impact on oral health. Coordinating care between medical and dental providers can be challenging owing to the traditional separation of medical and dental education and practice sites.

A new interprofessional education initiative model between dental and medical students at Boston University is preparing dental and medical students to communicate with each other and work together to provide comprehensive and coordinated care for their patients. Previous research has shown that students trained with an interprofessional approach to education are more likely to become collaborative team members. These students are more likely to show respect and positive attitudes toward each other on future interprofessional teams and work together to improve patient outcomes. The Boston University model of interprofessional education includes a didactic module on oral and systemic health for older adults and hands on experience of intraoral screenings for medical students taught by dental students.

This article uses 2 patient case studies to help illustrate interprofessional collaborative practice. The first is an example of a successful dental–medical collaboration and a second case is one with an unsuccessful oral health outcome. In the future, more interprofessional training opportunities for students in dental and medical schools may lead to better interprofessional clinician communication and increased instances of successful patient clinical outcomes.

Interprofessional collaborative practice improves patient outcomes in geriatric patient care

Good oral health is vital for function, comfort, and communication, and is a critical component of overall health. Oral diseases such as dental caries (cavities/decay), periodontal disease, and oral cancer may lead to pain, functional limitations, and decreased quality of life for patients. A recent study found that many older adults, including those aged 70, 80, 90, and 100 and older are retaining their natural dentition over their lifetime, with good oral health often an indicator of good systemic health. An increased understanding of the linkages between oral and systemic health, especially the association of periodontal disease with atherosclerotic vascular disease, diabetes, and stroke, heightens the need to maintain optimal oral health for older adults. Collaboration with nonoral health care providers, as well as the patient’s family and caregivers, are key to optimal dental treatment of older adults with multiple comorbidities.

Interprofessional team-based competencies ( Table 1 ) provide a framework for dentists collaborating with nondental health care providers in caring for older and frail patients. The competencies include clearly communication of the importance of integrating dental care into the patient’s overall treatment plan, communication between health care providers, defining the rolls of various providers, and how to best work together for optimal patient care. Consideration of interprofessional collaboration opportunities regarding geriatric medical domains and their impacts on oral health should be made ( Table 2 ).

| Interprofessional Team Core Competencies | General Characteristics | Geriatric Oral Health |

|---|---|---|

| Values and ethics for interprofessional practice | Patient and family as partners in team effort Respect and value of other members of the health care team |

Patient-centered care for geriatric patients Educating medical providers on the importance of dental care for their patients at all ages and stages of life |

| Roles and responsibilities | Understand the skill set of the other professions Engage diverse health care professionals to improve the patient’s health |

Cross-referrals between dental and nondental providers Interprofessional education at all education levels |

| Interprofessional communication | Communicating effectively with other members of the health care team | Using communication tools such as teleconferences or Skype to facilitate effective communication |

| Teams and team work | Cooperating in patient centered delivery of care | Jointly develop comprehensive care plan that incorporates all disciplines Educating dental and medical providers about options to provide dental care in a nondental setting |

| Geriatric Domains | Geriatric Medical | Geriatric Dental | Strategies for Medical and Dental Providers |

|---|---|---|---|

| Medications | Polypharmacy, radiation treatment or other etiologies resulting in xerostomia, and/or dysphagia | Patients often suck on sugar candies or consume high-sugar drinks to relieve symptoms of xerostomia and/or dysphagia, which may result in rampant caries | Preemptive strategies include educating the patient and other health care providers that xerostomia is a possible adverse side effect of treatment Proactively advise patients to treat symptoms by sipping water, using sugar-free candies and gum and/or oral lubricant; consider use of daily fluoride treatment |

| Anticoagulant medication | Bleeding resulting from dental extractions | Need to consult patients’ physician regarding anticoagulant therapy before a surgical procedure(s) | |

| Mobility | Patient has a history of falling or is wheelchair bound | Patient may fall in office. Limited room for wheelchair in office |

Clear hallways and operatory of potential fall hazards Design dental offices and bathrooms for wheelchair accessibility |

| Patient is homebound | Limited or no access to dental care | Educate family and other caregivers to assist homebound patients in daily oral hygiene procedures Dentists can consider making a home dental visit to treat patient |

|

| Cognitive function | Short-term memory loss Dementia Depression |

Poor oral hygiene Losing dentures |

Frequent hygiene recall visits Extract nonsalvageable teeth Engage caregivers to help keep track of dentures |

| Social support | Little social support: formal (visiting nurse, home health aide, Meals on Wheels) or informal (family, neighbors, etc) | Inadequate and poor nutrition Caries and periodontal disease |

Encourage and train informal and formal caregivers to provide oral hygiene assistance Use social service agencies for local resources |

| Physical impairment | Osteoarthritis Vision loss Hearing loss |

Inability to grasp toothbrush handle or floss Difficulty seeing teeth to clean adequately Trouble hearing oral hygiene instructions |

Modifying tooth brush handle with aluminum foil or tennis ball Use of children’s size electric toothbrush Large print handouts of oral hygiene instructions |

Boston Medical Center geriatrics: a successful interprofessional collaborative practice model

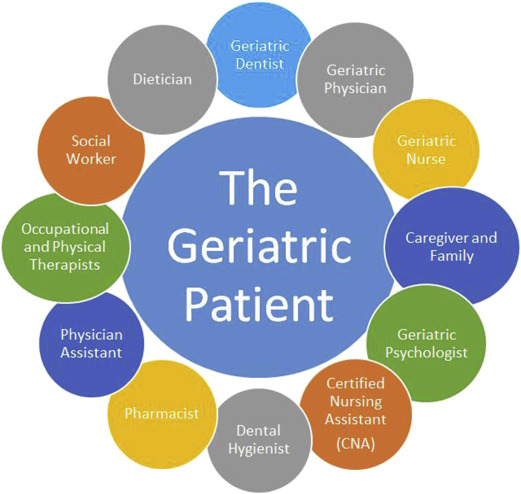

At Boston Medical Center, homebound older adults receive coordinated care from a team of geriatric medical, psychiatry and dental fellows and faculty, including dentists, physicians, nurses, and allied health professionals ( Fig. 1 ). The important role of caregivers and family members in helping the older homebound patients is recognized, valued, and included in caregiving and treatment decision making.

Interprofessional components of the geriatrics training for dentists and primary care physicians (PCPs) contributing to successful collaborative practice include case discussions of patients’ comorbidities with primary health care providers, complex case discussions with medical and dental components resulting in collaborative treatment planning, and interdisciplinary and evidence-based medical and dental case conferences.

Case study 1: Denture fabrication for a medically complex older adult in a nontraditional health care setting with a collaborative team

An 84-year-old homebound man with a medical history significant for chronic kidney disease, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, vision impairment (legal blindness), depression, and recent weight loss was referred to geriatric dental medicine for comprehensive oral evaluation owing to a broken upper denture and weight loss. Documented in the electronic medical record notes by the PCP were periods that the patient was argumentative and depressed, as well as a diagnosis of “failure to thrive.”

A discussion between the geriatric dentist, physician, and nurse case manager provided the dental team with the knowledge that the patient would likely cooperate with an oral health assessment and dental treatment and that the family was supportive of the treatment (see Fig. 1 ). The initial oral health assessment found our patient wearing ill-fitting upper and lower dentures, with a fractured acrylic flange in the maxillary buccal vestibule.

Team members included the geriatric dentist, PCP, and 2 fourth-year dental students. The entire team, including the patient and his wife, met in the same room and discussed the treatment plan. Under the direct supervision of the attending geriatric dentist, the students provided the treatment for the patient throughout the denture fabrication process, including preliminary impressions, final impressions, intermaxillary records, tooth and denture base shade selection, tooth try-in, denture insertion, and postinsertion adjustment visits as needed.

Medical concerns of note to the dental team included the patient’s decreased food intake with associated weight loss and the patient’s diagnosis of depression. The day of the first denture fabrication visit, the dental team stood by ready to go for a few minutes while the patient finished his breakfast. During this time the dental team took the opportunity to manage the expectations of the patient, his wife, and his son for the new dentures. Once the patient was ready, the students took the time necessary to develop a rapport with the patient, including asking him what kind of music he would like them to play on their smartphone during the visit. Upon learning that he was a retired choir director, the students promised him that they would “hold a concert” with him, that is, play piano and sing, after the last appointment.

After that seminal moment and until treatment was completed, the patient would anxiously await the arrival of the dental team. He would be on time and dressed up in a button-down shirt and tie. The patient and his family looked forward to each visit, appreciated the fact that the patient was offered the opportunity to select the music playing on the student’s smartphone during each visit, and celebrated the end of the treatment with a music recital, including the patient playing the piano and singing with the students. Six months after completion of the case after a follow-up by the PCP, the patient’s PCP reported that the patient had gained weight and was now actively engaging in social situations, a far cry from the man they met about 7 months earlier.

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses