With the growing complexity of health care, interprofessional communication and collaboration are essential to optimize the care of dental patients, including consideration of genetics. A dental case exemplifies the challenges and benefits of an interprofessional approach to managing pediatric patients with oligodontia and a family history of colon cancer. The interprofessional team includes dental, genetic, nutritional, and surgical experts.

Key points

- •

Application of genetic knowledge to clinical practice is an essential part of interprofessional collaborative practice.

- •

Interprofessional teams are required to optimize the implementation of genetic technology and information to the total health needs of patients.

- •

Interprofessional communication improves optimal care for all patients because of the common language among health care providers.

- •

Opportunities for genetic education as part of an interprofessional team approach are essential for not only oral health care providers but all health care providers.

Introduction

Given the growing complexity of health care, there is an increasing need for a collaborative approach among all health care providers in providing effective patient care. Interprofessional communication and collaboration are especially essential in the combined use of genetic analyses/counseling and how specific genotypes/phenotypes manifest poor oral health outcomes. However, dental clinicians often do not have appropriate training to interact with genetics teams in terms of proper consulting strategies, and often genetic counselors are not fully aware of oral manifestations of genetic diseases. As such, there is a growing need for more effective strategies of communication and collaboration between the two disciplines. In addition, patients or their representatives face the challenge of communicating between the two clinical advocates. A lack of an integrated health care record, and separate billing and reimbursement programs, compound the difficulties of getting appropriate clinical care.

Dental education in the United States has traditionally developed along the independent health educational paradigm. The training of students within independent and isolated educational systems contributes to poor communication and inadequate collaboration among clinicians in distinct health disciplines. This situation can result in poor, and in some cases inadequate, patient care in areas that span traditional care areas of health disciplines. This is evident in the emerging field of clinical genetics. Dentists often do not receive training in human genetics and are not prepared to interpret new developments that may support previous observations. The advent of sequencing the human genome has resulted in genetic testing, including some offered direct to consumers and direct to consumers through clinicians, which has created challenges to health care professionals in general because many developments have surpassed clinical training. Challenges include whether genetic testing is available for certain conditions as well as whether the genetic tests offered are valid and useful. In many cases, determination of the clinical validity and utility of genetic testing requires experts from different disciplines. The need for dentists to collaborate interprofessionally is clearly shown in genetics. This article describes an innovative model for integrating genetic counseling and how it applies to the oral and overall health of patients within an interprofessional collaborative practice setting by using a case approach.

Introduction

Given the growing complexity of health care, there is an increasing need for a collaborative approach among all health care providers in providing effective patient care. Interprofessional communication and collaboration are especially essential in the combined use of genetic analyses/counseling and how specific genotypes/phenotypes manifest poor oral health outcomes. However, dental clinicians often do not have appropriate training to interact with genetics teams in terms of proper consulting strategies, and often genetic counselors are not fully aware of oral manifestations of genetic diseases. As such, there is a growing need for more effective strategies of communication and collaboration between the two disciplines. In addition, patients or their representatives face the challenge of communicating between the two clinical advocates. A lack of an integrated health care record, and separate billing and reimbursement programs, compound the difficulties of getting appropriate clinical care.

Dental education in the United States has traditionally developed along the independent health educational paradigm. The training of students within independent and isolated educational systems contributes to poor communication and inadequate collaboration among clinicians in distinct health disciplines. This situation can result in poor, and in some cases inadequate, patient care in areas that span traditional care areas of health disciplines. This is evident in the emerging field of clinical genetics. Dentists often do not receive training in human genetics and are not prepared to interpret new developments that may support previous observations. The advent of sequencing the human genome has resulted in genetic testing, including some offered direct to consumers and direct to consumers through clinicians, which has created challenges to health care professionals in general because many developments have surpassed clinical training. Challenges include whether genetic testing is available for certain conditions as well as whether the genetic tests offered are valid and useful. In many cases, determination of the clinical validity and utility of genetic testing requires experts from different disciplines. The need for dentists to collaborate interprofessionally is clearly shown in genetics. This article describes an innovative model for integrating genetic counseling and how it applies to the oral and overall health of patients within an interprofessional collaborative practice setting by using a case approach.

An interprofessional case study of genetics in health care

Dental Student

A third year dental student is seeing a new patient in her community clinic. Her 14-year-old patient, Sarah, was brought to the clinic by her mother who is concerned that Sarah still has some of her baby teeth, whereas her younger sister has her permanent teeth. The dental student takes a panoramic radiograph and informs Sarah and her mother that Sarah has oligodontia (congenital absence of some of the teeth), because she is missing several molar teeth as well as all eight premolar teeth. The student discusses:

- 1.

The need to wait to do dental implants until Sarah’s jaw is more fully formed.

- 2.

Other restorative options to ensure that she has minimal issues with esthetics and function within her oral cavity.

Sarah’s mother comments that other relatives also have missing teeth, and says that she is worried that Sarah will die like her grandfather and his mother of colon cancer, because everyone in the family without all their teeth seem to die of cancer. Not knowing how to respond, the dental student reassures her that her teeth can be treated, and advises her not to worry about things that happen to older family members.

That night, the student has a nagging feeling that she gave her patient the wrong information. She therefore uses Google to check for more information. She searches on “oligodontia AND colon cancer.” The first three listings are for genetic changes associated with the combination of oligodontia and colon cancer. The next day, she discusses the case with her preceptor and realizes that she needs help to give the best information to this patient. They discuss her next step and it is decided that they should find a clinical geneticist. The preceptor does not know of one, so the student decides to try to find one. She goes back to Google and enters “How to find a geneticist” and an entry from the National Library of Medicine and the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics are the first two links. She chooses the top site on the list and goes to the National Library of Medicine site. Opening this web page shows a link to the National Society of Genetic Counselors. Once on the NSGC.com Web site, she enters the city name and finds a genetic counselor’s phone number. She decides to call and talk to the genetic counselor. Another resource she saw was The National Institutes of Health Genetics Home Reference at https://ghr.nlm.nih.gov/ , which added to her understanding of the people involved with genetic testing and health care.

Genetic Counselor

The genetic counselor who takes the dental student’s call is slightly surprised, but extremely pleased by the student’s approach to further identify resources for her patient’s total health and well-being. They discuss the patient’s concerns and the genetic counselor, who, like many, works at the local children’s hospital, recognizes that this patient would be best served by being evaluated by a genetic counselor trained in cancer and a medical geneticist (a physician who is trained to identify mild dysmorphisms which can be helpful in identifying an inherited syndrome). Together, they decide to refer the young patient to the medical geneticist and cancer genetic counselor at the children’s hospital, because other locations with a cancer genetic counselor do not have a genetic physician to evaluate her noncancer concerns. So far, this approach seems to be forming a foundation for an interprofessional collaborative (IPC) approach to the care of her dental patient.

Cancer Genetic Counselor

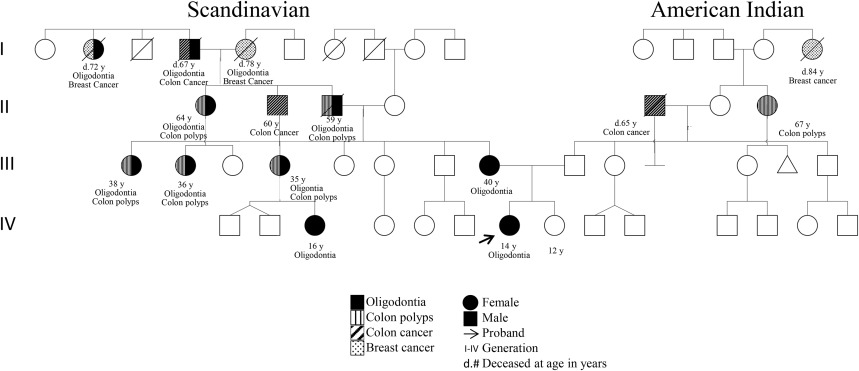

On the day of the young girl’s appointment, the genetic counselor begins the visit by discussing her concerns and reviewing her family history with the patient and her mother. A full 4-generation pedigree is created ( Fig. 1 ). Based on the history, it seems that the oligodontia is autosomal dominant, consistent with a single genetic change leading to the cause. Furthermore, most of the family members with oligodontia did have a cancer diagnosis in their lifetime. However, within the pedigree there was a female relative with normal dentition and breast cancer in her 60s and a male relative with normal dentition with colon cancer in his 70s. The patient’s mother is 35 years old, missing her maxillary lateral incisors and third molar teeth, and has no history of screening for colon cancer. Of the ten family members with oligodontia, six had colon polyps diagnosed on their first colonoscopy at age 50 years, and two had colon cancer diagnosed at age 50 years on their first colonoscopy.