The use of fluorides in dental public health programs has a long history. With the availability of fluoridation and other forms of fluorides, dental caries have declined dramatically in the United States. This article reviews some of the ways fluorides are used in public health programs and discusses issues related to their effectiveness, cost, and policy.

Fluorides in dental public health programs

Dental caries is a chronic disease that affects a large proportion of the population in the United States. Although dental caries has declined in the United States, almost 28% of 2- to 5-year-old children experience the disease . Among 16- to 19-year-old children, the average number of decayed, missing, and filled surfaces (DMFS) is 5.8. Adults 40 to 59 years of age have an average of 42 DMFS. Dental diseases account for 30% of all health care expenditures in children .

Theoretically, dental caries can be controlled by altering the bacterial flora in the mouth, modifying the diet, increasing the resistance of tooth to acid attack, or reversing the demineralization process. In practice, however, only the use of fluorides and sealants has been shown to be successful in reducing dental caries in populations . Therefore, the development of interventions that employ fluorides to prevent dental caries has been a large part of the dental public health effort. Traditionally, dental public health has focused on the community as a whole instead of the individual patient, and targeted interventions and policies to improve the health of the community. This article reviews some of the ways fluorides are used in public health programs and discusses issues related to the effectiveness, cost, and policy of these uses.

Fluoride and dental health

Frederick McKay, a Colorado dentist, noticed that clusters of individuals had stained teeth, and he hypothesized that these stains were related to some agent in the drinking water . Studies later identified the agent as the fluoride in water. During the epidemiologic investigations of the staining, H. T. Dean made the observation that children with mottled teeth seemed to have less tooth decay than those who did not have the mottling. Further studies clearly demonstrated the inverse association between the fluoride level in drinking water and the amount of tooth decay .

Four large-scale community studies were initiated in the period of 1945 to 1947 to assess whether adjusting the level of fluoride in drinking water to an optimal level could provide a beneficial caries-inhibiting effect. Water supplies in the communities of Grand Rapids, Michigan, Newburgh, New York, Evanston, Illinois, and Brantford, Ontario were adjusted, and this became the birth of fluoridation. The results obtained in these studies were compelling both because of the magnitude of the beneficial impact of fluoride on dental caries and because of the consistency observed across the studies . Since the early studies of water fluoridation, different approaches have been investigated to deliver fluoride to the oral environment, as water fluoridation is not practical in every community. Table 1 shows fluoride levels and the frequency of its use in public health programs.

| Program | Fluoride (F) levels | Frequency |

|---|---|---|

| Community water fluoridation | 0.7 mg/L –1.2 mg/L F | Daily |

| School-based fluoride rinse | 10 mL or 5 mL 0.2% sodium fluoride (9 mg F per 10 mL) | Weekly |

| Fluoride tablet | 0.25 mg to 1 mg F | Daily |

| Fluoride varnish | 0.3 mL–0.5 mL 5% sodium fluoride per application 22,600 ppm (2.26% F) | 3 to 6 month interval |

| Supervised tooth brushing | 1,000 ppm–1,100 ppm (1 mg to 1.1 mg F/g) | Twice daily |

| Salt fluoridation | 200 mg–250 mg F/kg salt | Daily |

Fluoride and dental health

Frederick McKay, a Colorado dentist, noticed that clusters of individuals had stained teeth, and he hypothesized that these stains were related to some agent in the drinking water . Studies later identified the agent as the fluoride in water. During the epidemiologic investigations of the staining, H. T. Dean made the observation that children with mottled teeth seemed to have less tooth decay than those who did not have the mottling. Further studies clearly demonstrated the inverse association between the fluoride level in drinking water and the amount of tooth decay .

Four large-scale community studies were initiated in the period of 1945 to 1947 to assess whether adjusting the level of fluoride in drinking water to an optimal level could provide a beneficial caries-inhibiting effect. Water supplies in the communities of Grand Rapids, Michigan, Newburgh, New York, Evanston, Illinois, and Brantford, Ontario were adjusted, and this became the birth of fluoridation. The results obtained in these studies were compelling both because of the magnitude of the beneficial impact of fluoride on dental caries and because of the consistency observed across the studies . Since the early studies of water fluoridation, different approaches have been investigated to deliver fluoride to the oral environment, as water fluoridation is not practical in every community. Table 1 shows fluoride levels and the frequency of its use in public health programs.

| Program | Fluoride (F) levels | Frequency |

|---|---|---|

| Community water fluoridation | 0.7 mg/L –1.2 mg/L F | Daily |

| School-based fluoride rinse | 10 mL or 5 mL 0.2% sodium fluoride (9 mg F per 10 mL) | Weekly |

| Fluoride tablet | 0.25 mg to 1 mg F | Daily |

| Fluoride varnish | 0.3 mL–0.5 mL 5% sodium fluoride per application 22,600 ppm (2.26% F) | 3 to 6 month interval |

| Supervised tooth brushing | 1,000 ppm–1,100 ppm (1 mg to 1.1 mg F/g) | Twice daily |

| Salt fluoridation | 200 mg–250 mg F/kg salt | Daily |

Mechanism of action of fluoride

The initial studies suggested that the beneficial effects of fluoride were a result of incorporation of fluoride into tooth crystals during its formation . The early studies also showed that there were posteruptive benefits from fluoridation . This led to studies of topical effects of fluoride on the tooth surface. The laboratory studies suggest that the predominant action of fluoride is in the process of remineralization and inhibition of demineralization of enamel . However, epidemiologic studies conducted in the 1950s, and more recent Australian studies, suggest important pre-eruptive benefits and support continuous exposure for the best outcome . These investigators noted that a thin fluorapatite coating on the surface of hydroxyapatite crystals could lead to decreased solubility of enamel. Regardless of the predominant mechanism of action, water is an efficient vehicle for delivering a low concentration of fluoride at high frequency: that is, as it is consumed throughout the day.

Community water fluoridation

Fluoridation of community drinking water is the precise adjustment of the existing natural fluoride concentration in drinking water to a safe level that is recommended for caries prevention. The United States Public Health Service has established the optimum concentration for fluoride in the water in the range of 0.7 mg/L to 1.2 mg/L . The optimum level for a region depends upon the annual average of the maximum daily air temperature. As of 2002, more than 170 million people in the United States, or 67% of those using public water supplies, drink water containing the recommended level of fluoride to prevent caries .

In the United States, 10 states have laws requiring communities to implement fluoridation if they meet certain conditions. In other states, the decision to fluoridate is usually made by individual communities. The water fluoridation program is usually administered under the supervision of state health and environmental agencies. Technical assistance is provided by the Division of Oral Health of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, whereas the Engineering and Administrative Recommendations for Water Fluoridation provides guidance for program administration .

Effectiveness of fluoridation

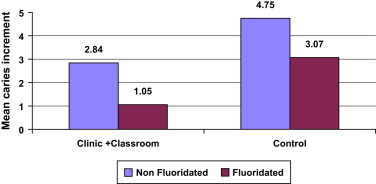

Early studies of water fluoridation suggested caries reductions in the range of 50% to 70% in children . To test the relative effectiveness and cost of various interventions under modern conditions, the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation supported a large-scale study of school children in 10 different cities. This study showed that water fluoridation was the most cost-effective means of reducing tooth decay in children . Fig. 1 compares the 4-year mean increment in caries between fluoridated and nonfluoridated communities among cohorts of fifth grade children that received class room and clinic interventions, and the cohort of longitudinal control groups receiving no intervention in fluoridated and nonfluoridated communities. Several recent authoritative reviews conducted in the United States, Australia, United Kingdom, and Ireland provide further evidence of the effectiveness of water fluoridation under conditions in which there is widespread exposure to fluoride from sources other than drinking water, such as fluoridated toothpastes and bottled beverages manufactured with fluoridated water . The National Health Center for Reviews and Dissemination, University of York, concluded that the best available evidence suggested that fluoridation of drinking water supplies reduced dental caries prevalence, both as measured by the proportion of children who are caries-free and by the mean change in decayed, missing, and filled teeth score .

An independent Task Force convened by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention that developed the Guide to Community Preventive Services , found strong evidence that water fluoridation is effective in reducing the cumulative caries experience in the population . The Task Force computed estimates of effectiveness based on three groups of studies. In studies examining the before and after measurements of caries at the tooth level, starting or continuing fluoridation decreased dental caries experience among children aged 4 to 17 years by a median of 29.1% during 3 to 12 years of follow-up. In studies that examined only post exposure measurements of caries at the tooth level, starting or continuing fluoridation decreased dental caries experience among children aged 4 to 17 years by a median of 50.7% during 3 to 12 years of follow-up.

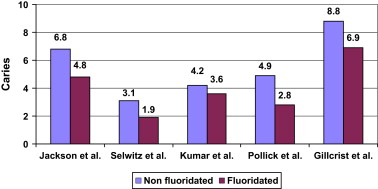

Fig. 2 shows several recent reports in the United States. The difference in dental caries between fluoridated and nonfluoridated communities is still noticeable, despite the ubiquitous presence of fluoride in food, water, and dental products . Additional supportive evidence comes from studies conducted in Australia and Ireland .

In a United States national survey, the mean DMFS of 5- to 17-year-old children with continuous residence in fluoridated areas under modern conditions of fluoride exposure was about 18% lower than in those with no exposure to fluoridation . The availability of other forms of fluoride and the diffusion of fluoride through beverages and foods processed in fluoridated communities are thought to provide an explanation for the diminished difference in caries observed in recent years between fluoridated and nonfluoridated communities . For example, children living in nonfluoridated areas in states such as Ohio, with more than 90% fluoridated areas, are more likely to receive the indirect benefit of water fluoridation through a diffusion effect (high diffusion) than that of in a state like New Jersey, where the fluoridation penetration is lower (low diffusion). According to Griffin and colleagues , on average, 12-year-old girls living in nonfluoridated areas with the least amount of exposure to a diffused effect experienced 1.44 more DMFS than did similar children residing in fluoridated communities. The indirect benefit of fluoridation, as evidenced by a comparison between children living in nonfluoridated communities with a high amount of fluoride exposure through diffusion and children living in nonfluoridated areas with the least amount of exposure to diffused effect, was an average of 1.09 fewer DMFS .

Cost effectiveness and cost savings

The National Preventive Dentistry Demonstration Program (NPDDP) reported that the reductions in decay attributable to water fluoridation were almost the same as those obtained with sealants . These investigators estimated the costs of maintaining a child in a sealant program to be $23 per year, while the annual per capita cost of water fluoridation is substantially lower. Many factors, such as equipment, installation, chemicals, and labor, affect the cost of fluoridating a community . The size of the community is a major determinant. According to the Guide to Community Preventive Services , the estimated median cost per person per year in the United States ranged from $2.70 for systems serving fewer than or equal to 5,000 people, to $0.40 for systems serving greater than or equal to 20,000 people .

Fluoridation has been shown to be cost saving. In 2001, Griffin and colleagues estimated that for every one dollar expended, fluoridation saved $38 in treatment costs. Using similar methods, O’Connell and colleagues estimated that the fluoridation program in Colorado was associated with an annual savings of $148.9 million (range, $115.1 to $187.2 million) in 2003, or an average of approximately $61 per person.

School-based fluoride mouth rinse programs

Fluoride mouth rinses were developed in the 1960s as an alternative to professional applications of gels and other topical fluoride products in school settings. With the availability of fluoridated water and fluoride containing toothpastes, these programs are now targeted to high-risk schools in nonfluoridated areas.

Typically, schools are provided with a year’s supply of mouth rinse that consists of unit doses of 0.2% neutral sodium fluoride solutions in 5-mL or 10-mL pouches, along with cups and napkins. Children in grades one through six participate after obtaining written permission from parents. The procedure consists of vigorously rinsing with 5 mL or 10 mL of solution for 60 seconds on a weekly basis in the classroom under the supervision of a teacher, nurse, or a dental hygienist. After the rinsing, the fluoride solution is expectorated into a cup, a napkin is inserted into the cup to absorb the solution, and both are disposed. Younger children are provided with only 5 mL of solution. Fluoride mouth rinse programs are not recommended for preschool children in the United States, as some children may swallow the solution intended for topical application.

There are several advantages with the school-based fluoride rinse program. Generally, compliance is better because children perform the procedure as a group activity under supervision. Children tend to complain less about the taste when compared with that of topical fluorides. Because fluoride rinses are generally administered by volunteers, the cost per child is less when compared with that of professionally applied topical fluorides. However, the program requires trained personnel, a supervising dentist or registered dental hygienist, physician or nurse practitioner, and cooperation from teachers and school authorities.

Effectiveness

School-based fluoride mouth rinse programs have been the subject of numerous reviews . A 17-site national school-based demonstration program showed that a protocol involving weekly rinsing with 0.2% sodium fluoride was a practical alternative to professional applications. Caries reductions ranging from 20% to 50% were observed. These estimates of caries reduction have been criticized because these programs relied on a before-and-after design, with no concurrent comparison group during a period of time when caries was declining in the United States. Analyses of the NPDDP data showed that dental health lessons, brushing and flossing, fluoride tablets and mouth rinsing, and professionally applied topical fluorides were not effective in reducing a substantial amount of dental decay, even when all of these procedures were used together . Another study on the island of Guam, using a combination of sealant and fluoride mouth rinsing, showed a 25.4% caries reduction, mainly on the proximal surfaces with fluoride mouth rinsing . Caries declined from 7.06 DMFS at the baseline to 2.93 DMFS after 10 years among 6- to 14-year-old children .

Cost-effectiveness

According to Garcia , the cost of the procedure in 1988 ranged between $0.52 and $1.78 per child per school year, depending on whether paid or volunteer adult supervisors were used. At present, the cost of the product to rinse weekly in a school for 36 weeks is approximately $2.64 per child. The NPDDP conducted during the late 1970s, when downward trends of caries rates were noted, questioned the cost-effectiveness of rinse programs . Many experts have concluded that fluoride mouth rinses may be more cost-effective when targeted at schoolchildren with high caries activity . Since then, many states, like New York, have targeted the fluoride rinse program to high-risk schools in nonfluoridated areas.

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses