3

History, examination, risk assessment, and treatment planning

M.L. Hunter and H.D. Rodd

Chapter contents

3.2.1 Other ethical considerations

3.7 Principles of treatment planning

3.7.1 Management of acute dental problems

3.7.4 Scheduling operative treatment

3.7.6 Treatment planning for general anaesthesia

3.7.7 Treatment planning for complex cases

3.1 Introduction

The provision of dental care for children presents some of the greatest challenges (and rewards) in clinical dental practice. High on the list of challenges is the need to devise a comprehensive yet realistic treatment plan for these young patients. Successful outcomes are very unlikely in the absence of thorough short- and long-term treatment planning. Furthermore, decision-making for children has to take into account many more factors than is the case for adults. This chapter aims to highlight how history-taking, examination, and risk assessment are all critical stages in the treatment planning process. Principles of good treatment planning will also be outlined.

3.2 Ethics and consent

When making decisions about children’s dental care, the clinician’s foremost ethical responsibility is to do no harm, to act in the child’s best interests, and to respect the child’s right to refuse treatment. However, reconciling this last principle with the preceding two might well present a dilemma, in which case the clinician should ask him/herself the following questions:

• Is what is being proposed really in the child’s best interest?

• Is the child happy to go ahead? If not, is there an alternative?

• If there is no alternative, what will really be the outcome if treatment does not proceed?

In most cases, failure to provide dental care for a child at a specific moment in time will not be life-threatening and a delay will be acceptable. However, there are circumstances in which failure to provide treatment may cause a child pain and distress. On these occasions, the clinician may feel that he/she has no alternative other than to proceed with treatment. Having weighed up the ethical considerations, he/she must then seek valid consent for what is proposed.

Valid consent to examination, investigation, or treatment is fundamental to the provision of dental care. The most important element of the consent process is ensuring that the patient/parent understands the nature and purpose of the proposed treatment, together with any alternatives available, and the potential benefits and risks. In this context, where clinician and patient/parent do not share a common language, the assistance of an interpreter is essential. (See Key Point 3.1.)

In all cases, the process whereby consent is gained should be clearly documented. The health record should include a note of all discussions and decisions about treatment, including a statement of the available options. Where physical intervention is considered necessary for examination and/or treatment, a discussion of its nature and use should be an integral part of the consent process.

Who is permitted to give consent for a child patient is dependent upon:

• the child’s age;

• the child’s level of understanding relative to the complexity of the proposed treatment;

• who else with an interest in the child is available in the circumstances to take part in the decision-making process;

• the relevant legislation in the country of residence.

The legal position surrounding consent for the treatment of children in the constituent countries of the UK is presented in detail in the British Society of Paediatric Dentistry’s policy document on consent and the use of physical intervention in the dental care of children (Nunn et al. 2008).

During most of childhood, the adult(s) with responsibility for the child will be required to make decisions about, and give consent for, the child’s dental treatment. In the majority of cases, it will be the child’s parents who have this role, thus giving rise to the legal concept of ‘parental responsibility’. However, parental responsibility is not given solely to parents, nor do all parents have ‘parental responsibility’ in the legal sense.

Adults acting in loco parentis (e.g. childminders, grandparents, and other relatives) have limited rights to consent on a child’s behalf. Treatment in the absence of a clear indication of parental wishes should only proceed if the child’s life is in danger or if the condition would deteriorate irretrievably as a result of failure to treat. Where treatment is not required urgently, the clinician should seek legal advice as to how to proceed. (See Key Point 3.2.)

It should be emphasized that parental rights exist for the benefit of the child and not the parent. Those with parental responsibility have no right to insist on treatment that is not in the best interests of the child, neither should they prohibit a necessary intervention. In cases where such conflict occurs, a second opinion should be sought, with immediate treatment being restricted to the provision of emergency care.

Parental responsibility extends to the right to access a child’s health records. However, if the child has capacity to consent, he/she must first indicate his/her agreement. Parental access to records must be withheld if it conflicts with the child’s best interests or the clinician has previously given the child an undertaking not to disclose specific aspects of their care. An exception to this principle is justifiable where failure to disclose would be contrary to the child’s best interests.

3.2.1 Other ethical considerations

Within the broader remit of providing a high-quality dental service for children, audit, service evaluation, and research have an important role to play. There is increasing recognition of the need to involve children actively, as service users, in the planning, monitoring, and development of health services, as well as in decision-making about their own treatment. Specific ethical principles and regulations govern the involvement of children in medical research; these may vary between countries. In the UK, any proposal to involve children in medical research or audit must be sanctioned by the appropriate ethics committee or audit/clinical governance group (Royal College of Paediatrics and Child Health 2000). Legally, valid consent should be obtained from the parent or guardian, and the agreement of school-age children should also be sought.

3.3 History

Taking a comprehensive case history is an essential prelude to clinical examination, diagnosis, and treatment planning. It is also an excellent opportunity for the dentist to establish a relationship with the child and his/her parent. Generally speaking, information is best gathered by way of a relaxed conversation with the child and his/her parent in which the dentist assumes the role of an interested listener rather than an inquisitor. While some clinicians may prefer to employ a pro forma to ensure the completeness of the process, this is less important than adherence to a set routine.

A complete case history should consist of:

• personal details

• presenting complaint(s)

• social history

• medical history

• dental history.

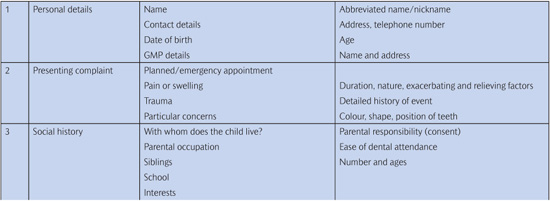

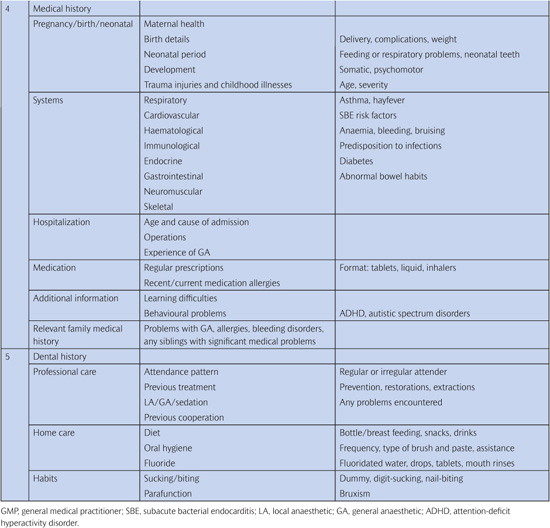

Table 3.1 summarizes the key information that should be included under each heading.

3.3.1 Personal details

A note should be made of the patient’s name (including any abbreviated name or nickname), age, address, and telephone number. Where these details have been entered in the case notes prior to the appointment they should be verified. Details of the patient’s medical practitioner should also be noted.

Table 3.1 History-taking for the paediatric dental patient

3.3.2 Presenting complaint(s)

It is important to ascertain from the child and his/her parent why the visit has been made or what they are seeking from treatment. It is good practice to ask this question to the child before involving the parent as this establishes the child’s importance in the process, although the dentist should be prepared to receive different answers from these two sources.

Where a child presents in pain or has a particular concern, this should be recorded in the child’s own words and, if relevant, the history of the present complaint (e.g. duration, mode of onset, progression) should be documented. It should be recognized that, even where other (perhaps more important) treatment is required, failure to take into consideration the patient’s/parent’s needs or wishes at this stage may be detrimental to both the development of the dentist–patient–parent relationship and the outcome of care.

3.3.3 Social (family) history

A child is a product of his/her environment. Factors such as whether both parents are alive and well, the number and age of siblings, the parents’ occupations, and ease of travel, as well as attendance at school or day-care facilities are all important if a realistic treatment plan is to be arrived at. However, since some parents will consider this kind of information confidential, the dentist may need to exercise considerable tact in order to obtain it.

This stage of history-taking also presents an opportunity to engage the child in conversation. In this way, the dentist gains an insight into the child’s interests (e.g. pets, favourite subjects at school, favourite pastimes) and is able to record potential topics of conversation that can act as ‘ice-breakers’ in future appointments.

3.3.4 Medical history

Various diseases or functional disturbances may directly or indirectly cause or predispose to oral problems. Likewise, they may affect the delivery of oral and dental care. Conditions that will be of significance include allergies, severe asthma, diabetes, cerebral palsy, cardiac conditions, haematological disorders, and oncology.

Wherever possible, a comprehensive medical history should commence with information relating to pregnancy and birth, the neonatal period, and early childhood. Indeed, asking a mother about her child’s health since birth will not infrequently stimulate the production of a complete medical history! Previous and current problems associated with each of the major systems should be elicited through careful questioning, and here a pro forma may well be helpful. Details about previous hospitalizations, operations (or planned operations), illnesses, allergies (particularly adverse reactions to drugs), and traumatic injuries should be recorded, as well as those relating to previous and current medical treatment. (See Key Point 3.3.)

It is useful to end by asking the parent whether there is anything else that they think the dentist should know about their child. (Sometimes, important details are not volunteered until this point!) This is a particularly useful approach in relation to children who suffer from behavioural or learning problems, such as attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) or autism. (See Key Point 3.4.)

It is important to bear in mind that many children with significant medical problems will have been subjected to multiple hospital admissions/attendances. These experiences may have a negative effect on the attitude of both the child and his/her parents towards dental treatment. In addition, dental care may not be seen as a priority in the context of total care.

Finally, a brief enquiry should also be made regarding the health of siblings and close family. Significant family medical problems, for instance problems in relation to general anaesthesia, may not only alert the practitioner to potential risks for the child, but also be factors to consider when planning treatment. Likewise, if the patient has a sick sibling, it may not be possible for the parents to commit to a prolonged course of dental treatment.

3.3.5 Dental history

A child’s previous dental experiences may affect the way in which he/she reacts to further treatment. Evaluation of a child’s previous behaviour requires the dentist to obtain information about the kind of dental treatment a child has received (including the method of pain and anxiety control that has been offered) and the way in which he/she has reacted to this. In so doing, specific procedures may emerge as having proved particularly problematic; such prior knowledge will enable the dentist to modify the treatment plan appropriately.

The dental history should also identify factors that have been responsible for existing oral and dental problems as well as those which might have an impact on future health. These include dietary, oral hygiene, dummy/digit sucking, and parafunctional habits. Specific questions should be asked about drinks (particularly the use of a bottle at bedtime in the younger age group), between-meal snacks, frequency of brushing, and type of toothpaste used.

Finally, a thorough dental history is an opportunity to evaluate the attitude of the parent to his/her child’s dental treatment. For example, the regularity of previous dental care may be an indicator of the value that the parent places on the child’s dental health. (See Key Point 3.5.)

3.4 Examination

3.4.1 First impressions

An initial impression of the child’s overall health and development can be gained as soon as he/she is greeted in the waiting room or enters the surgery. In particular, it is useful to note the following:

• General health—does the child look well?

• Overall physical and mental development—does it seem appropriate for the child’s chronological age?

• Weight—is the child grossly under- or overweight?

• Coordination—does the child have an abnormal gait or obvious motor impairment?

While the history is being taken, the clinician should also be making an ‘unofficial’ assessment of the child’s likely level of cooperation in order that the most appropriate approach for the examination can be adopted right from the start (hopefully saving both time and tears). Broadly speaking, prospective young patients may fall into one of the following categories:

• Happy and confident—this child is likely to hop into the chair for a check-up without further coaxing.

• A little anxious or shy but displaying some rapport with the dental team—this child will probably allow an examination after some simple acclimatization and reassurance (if the child is very young, the option of sitting on the parent’s knee could be given).

• Very frightened, crying, clutching their parent, avoiding eye contact, or not responding to direct questions—this child is unlikely to accept a conventional examination at this visit (though the child may allow a brief examination while sitting on a non-dental chair, perhaps even in the waiting room). Further acclimatization will be required before a thorough examination can be undertaken.

• Severe behavioural problem or learning disability—in a few cases, this may preclude the child from ever voluntarily accepting an examination. Restraint (with or without pharmacological management) may be indicated to facilitate an intra-oral examination.

(See Key Point 3.6.)

3.4.2 Physical intervention

In an ideal world, pre-cooperative children (see Section 4.3) would be given the time and opportunity to accept a dental examination voluntarily over a series of desensitizing visits. In reality, if a child presents with a reported problem but remains pre-cooperative after gentle coaxing and normal behaviour management strategies, it may be deemed necessary to carry out an examination in a controlled but restraining manner. This should always be viewed as a last resort in an ‘urgent’ clinical situation, and the child’s rights and best interests should remain paramount.

Physical intervention should only be considered for infants/very young children, or children with severe learning difficulties (provided that they are not too big or strong to make any restraint potentially dangerous or uncontrolled). The issue of informed consent is important here, as it is imperative that the need for the examination and the manner in which it is going to be conducted are clearly understood by all concerned. It is best to:

• explain in advance how the child is to be positioned;

• ask parents for their active help;

• give reassurance that the child is not going to be hurt in any way;

• document the event and outcomes.

In the most controlled approach, the child is laid across the parent’s knees with his/her head in the lap of the operator (Fig. 3.1). The parent is able to hold the child’s arms, although a dental nurse may need to rest/>

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses

Key Point 3.1

Key Point 3.1 Key Point 3.2

Key Point 3.2 Key Point 3.3

Key Point 3.3 Key Point 3.4

Key Point 3.4 Key Point 3.5

Key Point 3.5 Key Point 3.6

Key Point 3.6