18

Safeguarding children

J.C. Harris and R. Welbury

Chapter contents

18.2 Categories of abuse and neglect

18.3.2 A shared responsibility

18.3.3 The role of the dental team

18.4.1 Markers of physical abuse

18.4.2 Markers of emotional abuse

18.4.3 Markers of sexual abuse

18.6.3 What happens after referral

18.7.1 Information sharing and confidentiality

18.7.2 Forensic aspects of child protection practice

18.7.3 Giving evidence in court

18.8.1 Diagnosis of dental neglect

18.8.2 Management of dental neglect

18.9 Dental practice policy and procedures

18.1 Introduction

It is essential that everyone who provides dental care for children has an understanding of other factors that affect children’s lives. This includes non-dental aspects of their health, as discussed in previous chapters, and wider issues that affect children’s development and well-being. Child maltreatment is one such issue.

Abuse and neglect are forms of maltreatment of a child. Child maltreatment involves acts of commission or omission which result in harm to a child. When health professionals work with others to take action to protect children who are suffering, or are at risk of suffering, significant harm as a result of maltreatment, this is known as ‘child protection’. Child protection sits within the context of a wider agenda to ‘safeguard’ children. Safeguarding measures are actions taken to minimize the risks of harm to children and young people. This includes:

• protecting children from maltreatment;

• preventing impairment of children’s health or development;

• ensuring that children are growing up in a safe and caring environment.

This should enable children to have optimal life chances and to enter adulthood successfully (Box 18.1). The foundation for the success of such work is an acceptance and understanding of children’s internationally agreed human rights (Box 18.2). In this context the term ‘child’ includes children and young people up to the age of 18.

18.1.1 Historical aspects

Violence towards children has been noted between cultures and at different times within the same culture since early civilization. Infanticide has been documented in almost every culture, and ritualistic killing, maiming, and severe punishment of children in an attempt to educate them, exploit them, or rid them of evil spirits has been reported since early times. Ritualistic surgery or mutilation of children has been recorded as part of religious and ethnic traditions.

In the seventeenth century values started to change and incest was seen as a crime under church law, but until the eighteenth century society viewed children as possessions of their parents who were at liberty to treat them in any way they wished. In fact legislation to protect animals was introduced before children were afforded the same ‘privilege’.

Around the turn of the twentieth century social denial of abuse continued, but the implementation of the Prevention of Cruelty to Children Act 1904 gave local authorities the power, for the first time, to remove children from their parents. In 1908 incest became a criminal offence when the Punishment of Incest Act was passed in the British Parliament. The twentieth century saw the beginnings of an acknowledgement of the problem of child abuse and recognition that children needed protection, although society was very slow to accept that carers could deliberately harm children for whom they were responsible. In 1946 Caffey, a paediatric radiologist, described bone lesions and subdural haematomas resulting from trauma, and in 1962 Kempe, a paediatrician, described ‘the battered child syndrome’ (Kempe et al. 1962).

The term ‘non-accidental injury’ (NAI) became the medically accepted label for this syndrome in the UK, and doctors became increasingly involved with social workers and the police in its diagnosis. In the 1980s the problem of sexual abuse began to be seriously highlighted both in society and in the medical press. However, the actual diagnosis was still based on the medical model and, to compound the problem, society’s level of acknowledgement lagged behind that of professionals.

Despite the progress made on recognizing child abuse, defining what constitutes child abuse remains a matter of debate. Until recently, corporal punishment at school was deemed by society not only acceptable but also necessary. Yet nowadays previously widely accepted and almost universal practices such as caning of schoolchildren have been incorporated into the widening spectrum of child abuse. Even today the debate continues as to the appropriateness of smacking children to enforce discipline.

Today it is recognized that NAI is just one aspect of a spectrum which encompasses other types of abuse and neglect, and the current preferred term is ‘child maltreatment’. The primary aim of all professionals involved in the child protection process is to ensure the safety of the child. The secondary aim is to provide help and counselling for the parents or caregivers so that the abuse stops. (See Key Points 18.1.)

18.2 Categories of abuse and neglect

Somebody may abuse or neglect a child by inflicting harm, or by failing to act to prevent harm. Children may be abused in a family or in an institutional or community setting, by those known to them, or, more rarely, by a stranger. They may be abused by an adult or adults, or by another child or children. There are four categories of child maltreatment.

18.2.1 Physical abuse

Physical abuse may involve hitting, shaking, throwing, poisoning, burning or scalding, drowning, suffocating, or otherwise causing physical harm to a child. Physical harm may also be caused when a parent or carer fabricates the symptoms of, or deliberately induces, illness in a child (formerly known as Munchausen syndrome by proxy or factitious illness by proxy).

18.2.2 Emotional abuse

Emotional abuse is the persistent emotional maltreatment of a child such as to cause severe and persistent adverse effects on the child’s emotional development. It may involve conveying to children that they are worthless or unloved, inadequate, or valued only in so far as they meet the needs of another person. It may feature age or developmentally inappropriate expectations being imposed on children. These may include interactions that are beyond the child’s developmental capability as well as overprotection and preventing participation in normal social interaction. It may involve seeing or hearing the ill-treatment of another. It may involve serious bullying, causing children frequently to feel frightened or in danger, or the exploitation or corruption of children. Some level of emotional abuse is involved in all types of maltreatment of a child, although it may occur alone.

18.3 Extent of the problem

18.3.1 Prevalence

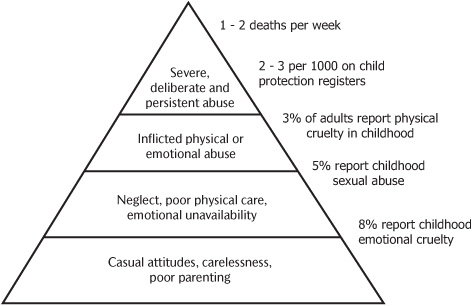

Child maltreatment is recognized to show a spectrum of severity, with larger numbers of children subject to careless or poor parenting and a small number subject to the most severe, persistent, or malicious abuse (Fig. 18.1). The true incidence of child abuse is difficult to ascertain. For instance, there are international differences in the acceptance of physical chastisement. In addition, today’s global society has led to the emergence of new aspects of child exploitation such as the international trafficking of children and internet child pornography.

Children who are recognized to be at risk of significant harm are made the subject of a ‘child protection plan’ (England and Wales) or placed on a ‘child protection register’ (Scotland). This allows us to identify at any one time the reasons for registration or being subject to a plan: an estimate of the prevalence of significant maltreatment.

18.2.3 Sexual abuse

Sexual abuse involves forcing or enticing a child or young person to take part in sexual activities, including prostitution, whether or not the child is aware of what is happening. The activities may involve physical contact, including penetrative acts (e.g. rape or oral sex) or non-penetrative acts (such as kissing or touching). They may include non-contact activities, such as involving children in looking at, or in the production of, sexual images, watching sexual activities, encouraging children to behave in sexually inappropriate ways, or grooming a child in preparation for abuse.

18.2.4 Neglect

Neglect is the persistent failure to meet a child’s basic physical and/or psychological needs which is likely to result in the serious impairment of the child’s health or development. Neglect may occur during pregnancy as a result of maternal substance abuse. Once a child is born, neglect may involve a parent or carer failing to provide adequate food, clothing, and shelter (including exclusion from home or abandonment), failing to protect a child from physical and emotional harm or danger, failing to ensure adequate supervision (including the use of inadequate caregivers), or failing to ensure access to appropriate medical care or treatment. It may also include neglect of, or unresponsiveness to, a child’s basic emotional needs. (See Key Point 18.2.)

Figure 18.1 The pyramid of severity of child maltreatment (figures are UK estimates).

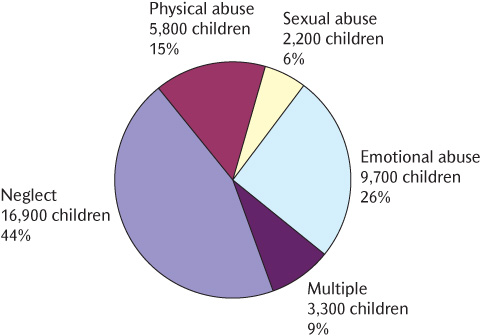

Figure 18.2 Children and young people with a child protection plan by category of abuse in England, 2009 (Department for Children, Schools and Families 2010).

Latest figures show that in England in 2010 there were 35,700 children who were the subject of a child protection plan, representing approximately 3 per 1000 of the population aged under 18. In recent years, 40–45% of cases were because of neglect, consistently the most common reason, 15–20% because of physical injury, 20–25% because of emotional abuse, 5–10% because of sexual abuse, and approximately 10% in mixed categories (Fig. 18.2). The highest rate of child protection plans is in children aged under 1 year. Young children are the most likely to be reported and registered because of the higher likelihood of very serious consequences of severe neglect and physical assault.

Children from all social, cultural, and religious backgrounds may be subject to maltreatment. Professionals need to be aware of and sensitive to differing family patterns, lifestyles, and child-rearing practices, but clear that child abuse cannot be condoned for religious or cultural reasons. Forced marriage, female genital mutilation, and ‘honour’-based violence are examples of newer challenges in this field. Working in a multiracial and multicultural society requires commitment to equality in meeting the needs of all children and families.

It is now recognized that if families can be identified and supported at a stage where they are ‘in need’, potential crises may be averted and there may be less requirement for child protection action. ‘Children in need’ can be defined as ‘those who require additional support or services to achieve their full potential’. In England there are currently 11–12 million children. Of these, 300 000–400 000 are recognized as being ‘children in need’.

18.3.2 A shared responsibility

Child protection is the responsibility of all members of society—it is everyone’s responsibility. In order to ensure that the task of protecting children is carried out effectively, different groups of professionals (Box 18.3) each have a specific role. Government guidance specifies how they should work together to fulfil this shared responsibility.

The development of legal and professional strategies and systems to safeguard children is an ongoing process. Whenever a death tragically occurs, an investigation is carried out to see what lessons can be learned. These often highlight the complexity of the process and reveal potential loopholes in a system designed to protect those who are most vulnerable. There can never be complacency in child protection. Four areas are recurrently identified where professional practice could be improved:

• recognition

• communication

• procedures

• record-keeping.

18.3.3 The role of the dental team

The dental team is well placed to take part in the shared responsibility of protecting children. The reasons for this include the following:

• Dentists are skilled at examining the head and neck and recording their findings. The head and neck is frequently a site of injury in physical abuse.

• Untreated dental disease may itself be a sign of neglect.

• Children often attend the dentist regularly, even when they may have little or no contact with other health services.

• Dentists often treat more than one family member, so may get to know about wider issues that impact on a child’s well-being.

Dental professionals may observe the signs of abuse or neglect, or hear something that causes them concern about a child. Child protection concerns may also come to the attention of dental teams that only treat adults, so they also need to know about these issues and how to respond. Research has shown that dental professionals often lack confidence in this field of practice. However, it is never a task that the dental team faces alone. Advice and support are always available from experienced child protection professionals. (See Key Points 18.3.)

18.4 Recognizing the signs

Abuse or neglect may present to the dental team in a number of different ways:

• through a direct allegation (sometimes termed a ‘disclosure’ made by the child, a parent, or some other person);

• through signs and symptoms which are suggestive of maltreatment;

• through observations of child behaviour or parent–child interaction.

However it presents, any concerns should be taken seriously and appropriate action taken. It is assumed that the dentist will be examining a child who is fully dressed, so signs and symptoms related to areas not covered by clothes will be the focus of discussion.

18.4.1 Markers of physical abuse

There are no hard-and-fast rules to make the diagnosis of physical abuse easier. The following list constitutes seven classic indicators to the diagnosis. None of them is absolute on its own, and neither does the absence of any of them preclude the diagnosis of physical abuse.

• There is a delay in seeking medical help (or medical help is not sought at all).

• The story of the ‘accident’ is vague and lacking in detail, and may vary with each telling and from person to person.

• The account of the accident is not compatible with the injury observed.

• The parents’ mood is abnormal. Normal parents are full of creative anxiety for the child, while abusing parents tend to be more preoccupied with their own problems—for example, how they can return home as soon as possible.

• The parents’ behaviour gives cause for concern—for example, they may become hostile and rebut accusations that have not been made.

• The child’s appearance and interaction with the parents are abnormal. The child may look sad, withdrawn, or frightened.

• The child may say something concerning the injury that gives you cause for concern.

Orofacial trauma occurs in at least 50% of children diagnosed with physical abuse. It is always important to remember that a child with one injury may have further injuries that are not visible so, where possible, arrangements should be made for the child to have a comprehensive medical examination. Although the face often seems to be the focus of impulsive violence, facial fractures are not frequent. It is extremely important to state that there are no injuries that are pathognomonic of (i.e. only occur in or prove) child abuse. Any text that suggests so is incorrect. However, some injuries or patterns of injury will be highly suggestive of it.

The assessment of any physical injury involves three stages:

• evaluating the injury itself, its extent, site, and any particular patterns;

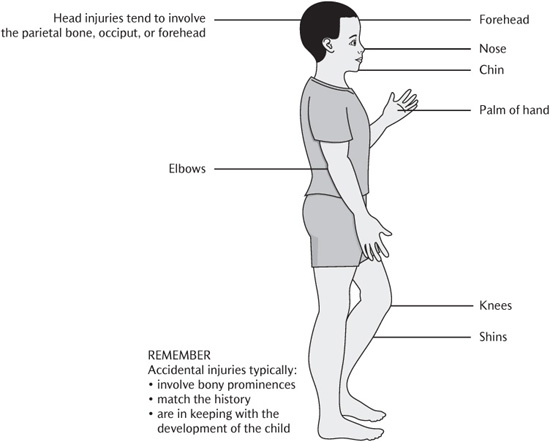

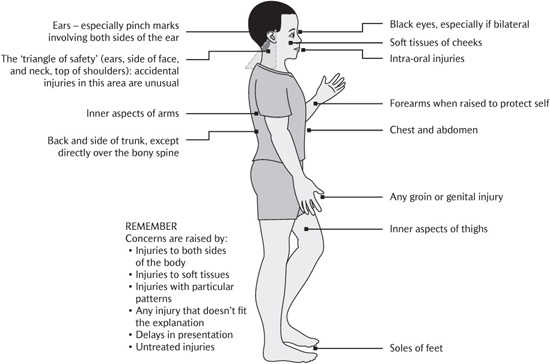

• taking a history with a focus on understanding how and why the injury occurred and whether the findings match the story given (Figs 18.3 and 18.4);

• exploring the broader picture, including aspects of the child’s behaviour, the parent–child interaction, underlying risk factors, or markers of emotional abuse or neglect.

Bruising

Accidental falls rarely cause bruises to the soft tissues of the cheek, but instead tend to involve the skin overlying bony prominences such as the forehead or cheekbone. Inflicted bruises may occur at typical sites or fit recognizable patterns. Bruising in babies or children who are not independently mobile are a cause for concern. Multiple bruises in clusters or of uniform shape are suggestive of physical abuse and may occur with older injuries. The clinical dating of bruises according to colour is inaccurate. However, multiple bruises of different ages are suggestive of physical abuse.

Bruises on the ear may result from being pinched or pulled by the ear (Fig. 18.5) and there will often be a matching bruise on the posterior surface of the ear. Bruises or cuts on the neck may result from choking or strangling by a human hand, a cord, or some sort of collar. Accidents to this site are extremely rare and should be looked upon with suspicion.

Particular patterns of bruises may be caused by pinching (paired, oval, or round bruises) (Fig. 18.6), grabbing (a round thumb imprint on one cheek with three or four fingertip bruises on the other) (Fig. 18.7), or hand slaps (parallel linear, often petechial, marks on the cheek at finger-width spacing) (Fig. 18.8). Bizarrely shaped bruises with sharp borders are nearly always deliberately inflicted. If there is a pattern on the inflicting implement, this may be duplicated in the bruise—so-called tattoo bruising.

Figure 18.3 Typical sites of accidental injuries. (Reproduced from Harris, J.C. et al., Child protection and the dental team. © COPDEND 2006.)

Figure 18.4 Typical sites of injuries that should raise concern. (Reproduced from Harris, J.C. et al., Child protection and the dental team. © COPDEND 2006.)

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses

Key Points 18.1

Key Points 18.1 Key Point 18.2

Key Point 18.2

Key Points 18.3

Key Points 18.3