11 Leukoplakia, Oral Dysplasia, and Squamous Cell Carcinoma

Leukoplakia, Erythroplakia, and Dysplasia

Leukoplakia is not any white plaque but rather a white plaque that does not conform clinically or histopathologically to any specific disease and cannot be attributed to reactive, frictional, or traumatic causes. As such, it is a clinical term only and is used when other specific histopathologic and clinical entities are excluded (especially frictional keratoses [see Chapter 10]). Leukoplakia is the most common precursor lesion before invasive cancer develops.

Development of Invasive Carcinoma

• Of all leukoplakias, 9% to 37% (the most recent figure being 47%) represent dysplasia, carcinoma in situ, or invasive carcinoma at time of biopsy.

• Over time, 16% to 36% of dysplasias develop invasive carcinoma.

• Over time, up to 16% of benign hyperkeratosis without dysplasia will develop dysplasia and/or carcinoma.

• The highest incidence of malignancy is on the ventral tongue, floor of mouth, and soft palate, which are all nonkeratinized sites.

• Over time, 60% to 100% of proliferative leukoplakias develop carcinoma.

Clinical Features

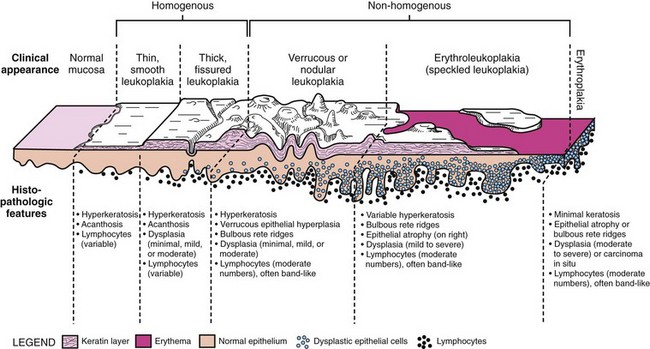

• All forms of leukoplakia are more often seen in older individuals. Correlation of histopathologic findings with clinical appearance of lesions is of the utmost importancce in the accurate diagnosis of dysplasia.

Localized Leukoplakia

• Localized leukoplakia (at a single site) is more common in men and is strongly associated with smoking; leukoplakia are identified:

• Verrucous hyperplasia of buccal mucosa may be associated with an areca nut habit.

Proliferative Leukoplakia

• Proliferative form is multifocal or extensively affects contiguous sites and often affects gingiva.

• More common in women, it is not strongly associated with smoking; it is present and progressive over 10 to 20 years.

• Homogeneous forms are uncommon; most are nonhomogeneous and usually verrucous/nodular or erythroleukoplakic (Fig. 11-3).

Erythroleukoplakia

• Erythroleukoplakic form is often clinically misdiagnosed as lichen planus because of multifocality and bilaterality; demarcation is usually best seen around the white/keratotic areas of the lesion, which may show fissuring.

• Erythroplakia appears as a velvety red plaque, usually painless; it is much less common than leukoplakia; more than 90% of these lesions are dysplastic or malignant at the time of diagnosis (Fig. 11-4).

Etiopathogenesis and Histopathologic Features

Architectural Evidence of Dysplasia

Features of dysplasia that occur in the absence of, or with minimal evidence of, cytologic dysplasia are often observed in clinical lesions of verrucous and proliferative leukoplakias (Table 11-1)

• Bulky epithelial proliferation, especially if endophytic and without leukocyte exocytosis or spongiosis (Figs. 11-5 to 11-7); many of these are thick plaques or masses clinically

• Papillary or verrucous epithelial proliferation, broad based, in an exophytic or endophytic configuration, often bulky (Figs. 11-8 to 11-10)

• Bulbous or drop-shaped rete ridges (Fig. 11-11)

• Sharp demarcation of the keratotic area from the adjacent normal epithelium and “skip” areas of normal mucosa sandwiched by hyperkeratotic or dysplastic epithelium (Figs. 11-12 and 11-13)

• Marked hyperorthokeratosis with epithelial atrophy (usually sharply demarcated) in the absence of inflammation and/or not representing a specific disease entity (such as atrophic or treated lichen planus) should be viewed with suspicion; not all dysplasias are hyperplastic lesions

• Sixteen percent of so-called benign hyperkeratoses developing into carcinoma owing to underdiagnosis of these lesions with minimal cytologic atypia.

| Architectural features |

Cytologic Evidence of Dysplasia

Cytologic features are similar to those at other mucosal sites and are readily noted on exfoliative cytology (see Table 11-1); reactive epithelial atypia from inflammation may show the same features to a lesser degree.

• Graded mild (less than one third of the thickness of the epithelium involved by dysplasia), moderate (one third to two thirds), and severe (more than two thirds, not including carcinoma in situ) by convention (Figs. 11-14 to 11-16); carcinoma in situ shows full thickness involvement (Fig. 11-17); presence of a lymphocytic band at the interface is common and does not necessarily represent preexisting lichen planus; this is likely a T cell response to altered antigens on dysplastic keratinocytes.

• Involvement of ducts by dysplasia must be documented, because deep margins may not be clear of dysplasia if deep portions of duct are involved; this feature is associated with an increased rate of local recurrence (Figs. 11-18 and 11-19).

• Molecular markers and presence of high-risk HPV is not consistently predictive of subsequent development of invasive carcinoma.

Differential Diagnosis

• Reactive atypia is sometimes difficult to differentiate from true dysplasia, especially in the presence of reepithelialization and healing ulceration; if one cannot be sure, suggest using the phrases likely reactive, unsure if reactive, unlikely reactive, or suspicious for dysplasia to guide patient management.

• Lichen planus or lichenoid mucositis with reactive atypia tends to show squamatization of basal cells (instead of basal cell hyperplasia) and colloid body formation; multinucleated epithelial cells with finely dispersed chromatin and abundant cytoplasm are often seen in reactive lesions (Fig. 11-20).

• Candidiasis may show significant reactive atypia; to complicate matters, dysplastic epithelium is often colonized by Candida, likely because of breakdown of immune surveillance in some cases.

Management and Prognosis

• Multiple biopsies should be performed for nonhomogeneous leukoplakia and proliferative leukoplakia.

• All dysplasias, including mild dysplasias (not reactive atypia) should be carefully followed or excised/ablated, depending on the clinical situation (e.g., high-risk site and high-risk history); recurrence occurs in 30% to 60% of cases.

• Cases that are suspicious for dysplasia because of architectural abnormalities without cytologic evidence of dysplasia, location at high-risk sites, or sharp demarcation may be candidates for narrow excision or ablation, unless morbidity is unacceptable.

Bagan J, Scully C, Jimenez Y, Martorell M. Proliferative verrucous leukoplakia: a concise update. Oral Dis. 2010;16:328-332.

Barnes L, Eveson J, Reichart P, Sidransky D, editors. Pathology and Genetics of Head and Neck Tumors. Lyon, France: IARC Press, 2005.

Brandwein-Gensler M, Smith RV. Prognostic indicators in head and neck oncology including the new 7th edition of the AJCC staging system. Head Neck Pathol. 2010;4:53-61.

Daley TD, Lovas JG, Peters E, et al. Salivary gland duct involvement in oral epithelial dysplasia and squamous cell carcinoma. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 1996;81:186-192.

Gale N, Michaels L, Luzar B, et al. Current review on squamous intraepithelial lesions of the larynx. Histopathology. 2009;54:639-656.

Lee JJ, Hung HC, Cheng SJ, et al. Carcinoma and dysplasia in oral leukoplakias in Taiwan: prevalence and risk factors. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2006;101:472-480.

Napier SS, Speight PM. Natural history of potentially malignant oral lesions and conditions: an overview of the literature. J Oral Pathol Med. 2008;37:1-10.

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses