Viral hepatitis

Publisher Summary

Viral hepatitis, common with acquired immune deficiency syndrome (AIDS), is one of the few blood-borne viral hazards that the dentist has to contend with in his practice. Although the AIDS epidemic has aroused the greatest concern regarding disease transmission, hepatitis B infection can be more dangerous to the patient and the dentist, because of the relatively high infectivity of hepatitis B virus compared with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV). Hepatitis A occurs in parts of the world where sewage disposal measures and food hygiene are unsatisfactory. Although the transmission of the virus might rarely occur via contaminated needles, it is usually contracted by the faecal-oral route through contaminated food and water. Hepatitis B virus is usually spread by the parenteral route rather than the faeco-oral route. Non-A non-B (NANB) hepatitis has also been recognized. This disease, sometimes called hepatitis C, occurs most commonly after blood transfusion and parenteral drug abuse. However, delta hepatitis is caused by a recently discovered “defective” RNA virus, which coexists with the hepatitis B virus.

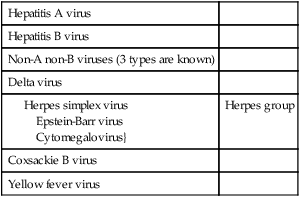

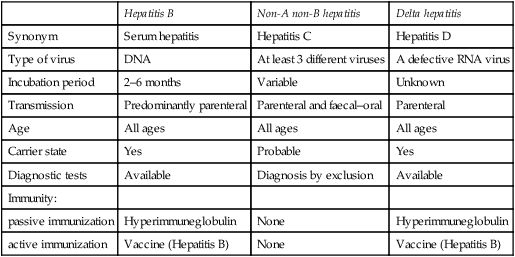

The term ’viral hepatitis’ is commonly used for several clinically similar diseases which cause inflammation of the liver but are epidemiologically and aetiologically distinct (Table 15.1). Two of these, hepatitis A (formerly called infectious hepatitis) and hepatitis B (formerly called serum hepatitis) are well characterized, while a third, non-A non-B hepatitis, is thought to be caused by at least three different agents. These viruses, together with the relatively recently discovered delta virus, are of concern in dentistry as they are responsible for the great majority of viral liver diseases. Table 15.2 shows the main differences between the hepatitis caused by hepatitis B, non-A non-B and delta viruses. It is worth remembering that hepatitis caused by the above agents are clinically indistinguishable, although they possess other differences.

Table 15.1

Aetiological agents of viral hepatitis

| Hepatitis A virus | |

| Hepatitis B virus | |

| Non-A non-B viruses (3 types are known) | |

| Delta virus | |

Table 15.2

Epidemiological and clinical features of three types of hepatitis viruses

| Hepatitis B | Non-A non-B hepatitis | Delta hepatitis | |

| Synonym | Serum hepatitis | Hepatitis C | Hepatitis D |

| Type of virus | DNA | At least 3 different viruses | A defective RNA virus |

| Incubation period | 2–6 months | Variable | Unknown |

| Transmission | Predominantly parenteral | Parenteral and faecal–oral | Parenteral |

| Age | All ages | All ages | All ages |

| Carrier state | Yes | Probable | Yes |

| Diagnostic tests | Available | Diagnosis by exclusion | Available |

| Immunity: | |||

| passive immunization | Hyperimmuneglobulin | None | Hyperimmuneglobulin |

| active immunization | Vaccine (Hepatitis B) | None | Vaccine (Hepatitis B) |

Hepatitis B

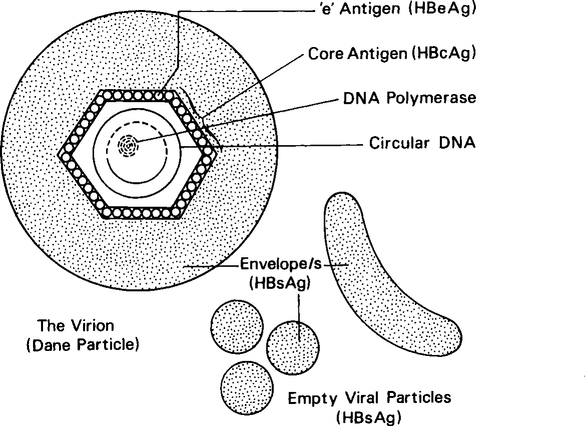

Hepatitis B infection is caused by the hepatitis B virus (HBV), a DNA hepadnavirus which is structurally and immunologically complex. Electron microscopy of HBV reveals three distinct particles, 42 nm Dane particle (the complete infective virus), 22 nm spheres, and tubular forms 22 nm in diameter and 100 nm in length (Figure. 15.1).

The central core of the hepatitis B virus consists of single-stranded DNA, an enzyme (DNA polymerase) and a core antigen (HBcAg). Although this antigen is rarely found in serum, a breakdown product of HBcAg, termed ‘e’ antigen (HBeAg), may be found in serum and is a marker of active infection. The terminology of hepatitis B virus-associated serological markers is given in Table 15.3.

Table 15.3

Terminology of hepatitis B virus-associated serological markers

| Name | Abbreviation |

| Hepatitis B Virus | HBV |

| Antigens: | |

| hepatitis B surface antigen | HBsAG |

| hepatitis B core antigen | HBcAg |

| hepatitis B ‘e’ antigen | HBeAg |

| DNA polymerase | DNA-P |

| Antibodies: | |

| antibody to HBsAg | Anti-HBs |

| antibody to HBcAg | Anti-HBc |

| antibody to HBeAg | Anti-HBe |

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses