Fixation of mandibular fractures using rigid hardware has gained wide acceptance over the past 3 decades. The goal of rigid internal fixation is to allow for fracture healing with limited, or no, time in maxillo-mandibular fixation. There has been significant evolution in plate and screw materials and design over the past 30 years. The term miniplate is used to describe a fracture plate with a screw diameter of 2.0 mm or less. With correct diagnosis and understanding of the forces affecting mandible fractures, miniplates can be applied transorally in various situations, allowing for less invasive treatment with open reduction of mandible fractures. This article describes the use of monocortical miniplates for the intraoral treatment of mandibular fractures.

Fixation of mandibular fractures using rigid hardware has gained wide acceptance over the past 3 decades. The goal of rigid internal fixation is to allow for fracture healing with limited, or no, time in maxillo-mandibular fixation (MMF). Originally internal fixation of mandibular fractures was accomplished with stainless steel plates. These plates were thick because of lack of material tensile strength and were combined with maxillo-mandibular fixation to prevent failure. There has been a significant evolution in plate and screw materials and design over the past 30 years. Today there are numerous companies offering a myriad of plates and instrument design for application in the craniomaxillofacial region.

The term miniplate is commonly used to describe a fracture plate with a screw diameter of 2.0 mm or less. These thin plates were originally reserved for treating facial fractures in low or non–load-bearing areas such as the mid-face. As experience with smaller fixation hardware evolved, miniplates gained increased use in the mandible. This led to research both “in vitro” and “in vivo” models of mandibular fractures widening the application of the small plates. With correct diagnosis and understanding of the forces affecting mandible fractures, miniplates can be applied transorally in a variety of situations. This allows for less invasive treatment with open reduction of mandible fractures.

Anatomic and physiologic considerations

When considering the use of miniplates for fixation of mandibular fractures, several factors must be considered. The first factor is the location and nature of the fracture. Mini-plates may be used for ramus, angle, body, or symphyseal fractures. Fractures with minimal comminution are the best suited for miniplate application and large intact bone segments provide the optimal situation for a successful result ( Fig. 1 ). Although miniplates can be used to secure smaller bone segments, excessive stripping of periosteal tissues compromises blood supply and can cause bone necrosis and sequestra in the mandible.

The fracture orientation in relation to the tension and compression forces of the mandible is another important variable. Under function, the mandible develops compressive forces at the inferior border while tension forces are located at mid body and the superior border. In addition, the anterior mandible has a double tension band in the symphysis region because of suprahyoid muscular pull. These factors must be considered when deciding on a treatment to avoid excessive mobility and potential splaying of fracture segments resulting in nonunion or malunion of the fracture.

Another consideration is the presence of teeth in the line of the fracture. Teeth may sometimes prevent adequate fracture reduction or may become a source of infection when luxated from their original alveolar position ( Figs. 2 and 3 ). This may require removal of the affecting tooth, leaving a thin residual cortical plate in the fracture area with inadequate strength to maintain fracture hardware. Also, teeth may limit the options for optimal placement without root damage.

Finally, infection is a known complication of all fracture repair modalities. Because mandibular miniplates are generally placed via intraoral approaches, some fractures may not be amenable to this technique. Mini-plates should not be used where access is not available for proper placement. Surgeons must also decide if it is prudent to place small hardware in an area of active infection. Because miniplates will allow for additional fracture flexure compared with larger fixation hardware, chronic infection may persist, resulting in nonunion.

Techniques

Mandibular angle fracture

The most popular use of miniplates for the mandible has been the use of the superior border plating technique for mandibular angle fractures. This technique was described by Michele Champy in 1986 and has become widely accepted as a preferred method of treating angle fractures. Since its inception, the technique has been the subject of multiple studies by many different authors giving the evidence-based data required to validate any surgical technique.

The superior border plate technique offers many advantages. First, it allows for a relatively rigid internal fixation of a mandibular angle fracture that prevents the proximal segment from displacing superiorly yielding a malunion. Second, it is placed via an intraoral approach avoiding any external facial scar, and possible damage to the facial nerve. Finally, it allows for early mobilization of the mandible avoiding the approximately 6 weeks of maxillo-mandibular fixation required of closed reductions.

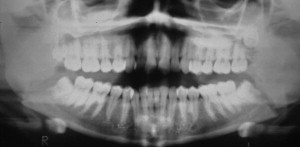

When considering the monocortical superior border plating, the surgeon must first examine the patient to assess for the fracture criteria discussed earlier. The ideal fracture will have minimal comminution with little displacement and an intact mucosal surface. Examine intraorally for steps, bony prominences, and any lacerations. An imaging study is done to correlate the clinical findings. Computed tomography is readily available today, however is not required in the case of isolated mandibular fracture injuries. Plain radiographic films with views in two planes and/or an orthopantogram will generally give the required diagnostic information.

The surgical procedure is typically performed in the operating room under general anesthesia. Nasal intubation avoids interference of an oral tube during the surgical procedure and application of MMF. A moist gauze throat pack will protect the airway from any foreign bodies such as screws or wires during the procedure. The authors prefer to perform a preop irrigation with Peridex to decrease the intraoral bacterial load to aid in reduction of postoperative infections. The first step in the procedure is to manually reduce the fracture to ensure the patient can be placed into a correct central occlusal relationship. Once this is confirmed, one can commence with the placement of arch bars secured using 24- to 26-gauge wires. It is very important to examine the mucosa in the area of the angle to visualize any lacerations that may be present. These lacerations may be incorporated into the incision to prevent additional tissue trauma and necrosis of small tissue islands with compromised blood supply. If the mucosa is intact, the mouth is propped open and an incision is created in the posterior vestibule paralleling the external oblique ridge. The incision may be created with a blade, or a needle-tip cautery device to reduce intraoperative bleeding. An incision is created through mucosa, muscle, and down to bone by angling the scalpel or cautery toward the mandible. It is important to place the incision lateral to the mandible to help prevent postoperative plate dehiscence and ensure it is long enough for adequate exposure ( Fig. 4 ). In addition, the lateral placement facilitates suturing when the patient is released from MMF. A periosteal elevator is used to expose the mandible distal and proximal to the fracture line and free any entrapped tissue present in the fracture line. Any old blood clot, fibrous tissue, or unsupported bone fragment area is debrided. If a third molar is present in the fracture area that may compromise reduction or healing, it should be removed at this time. Bone should be removed judiciously from the third molar area when removing teeth. Overaggressive bone removal may result in inadequate bone quantity or quality and compromise screw placement for fixation.