The older patient often presents with clinically challenging dental problems combined with complex medical, social, psychological, and financial barriers to oral health. Through careful consideration, the clinician can design a thoughtfully sequenced treatment plan that addresses dental conditions and facilitates improved oral health. Several models serve to guide the clinician with this endeavor. Treatment planning for a medically complex patient with xerostomia and dementia involves a great deal of uncertainty, which may be attenuated by flexibility and good communication with the patient and all involved parties.

Key points

- •

Treatment planning for geriatric care is a dynamically informed process culminating from comprehensive diagnostic evaluation and informed consent.

- •

Geriatric patients presenting with multiple chronic conditions, medications, and complex sociobehavioral histories require a strategic, stepwise plan for disease treatment and oral health maintenance.

- •

Flexibility and good communication with the patient and other involved parties during treatment planning for older adults may attenuate uncertainties and lead to successful outcomes.

Introduction

Treatment planning in a healthy, older adult is usually straightforward, varying little from the process clinicians typically follow. Normal changes in the aging dentition can require very little modification to the usual treatment-planning process. Often, though, developing dental treatment plans for older adults is complicated by their declining status in general health, cognitive function, and functional ability.

This article briefly describes the profile of older adults in the United States, and discusses the dynamic process of treatment planning and obtaining informed consent. Next, various models for formulating alternative treatment plans are described. Finally, a case is presented that illustrates treatment planning for multiple chronic conditions and polypharmacy.

Introduction

Treatment planning in a healthy, older adult is usually straightforward, varying little from the process clinicians typically follow. Normal changes in the aging dentition can require very little modification to the usual treatment-planning process. Often, though, developing dental treatment plans for older adults is complicated by their declining status in general health, cognitive function, and functional ability.

This article briefly describes the profile of older adults in the United States, and discusses the dynamic process of treatment planning and obtaining informed consent. Next, various models for formulating alternative treatment plans are described. Finally, a case is presented that illustrates treatment planning for multiple chronic conditions and polypharmacy.

Profile of older adults

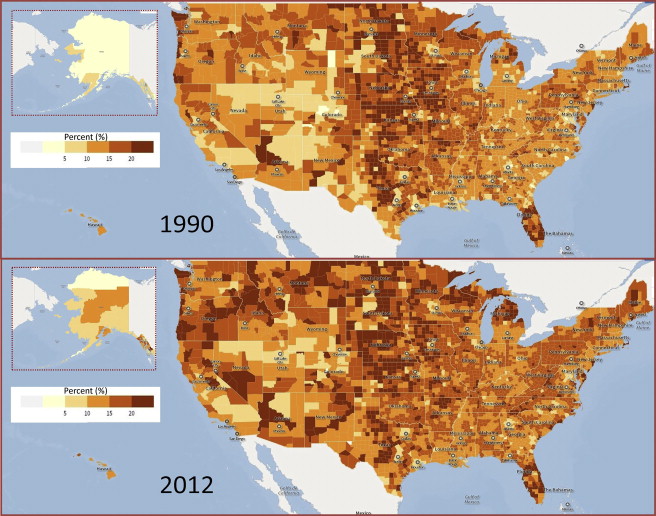

Thirteen percent of the United States population is 65 years and older, with the young-old (age 65–74 years) comprising 7%, the old (age 75–84) 4%, and the old-old (age ≥85) 2%. In large part because of the shift away from infectious diseases as the leading causes of death, Americans are living longer than ever before. In 1960, at birth Americans were expected to live 69.7 years; today they are expected to live at least 78 years. With a declining birth rate, the first group of baby-boomers reaching 65, and the increasing life expectancy, the United States is developing into an aging society ( Fig. 1 ). The life expectancy in 1960 for people age 65 was 14.3 years. Half a century later, life expectancy for older adults has increased to 19.1 years.

Although most people 65 years and older live in the community, only 3% at any given time live in a skilled nursing facility (SNF). However, the percentage of elderly living in SNFs increases with age; in 2010, less than 1% of the young-old and 13.5% of the old-old lived in an SNF. In addition to being older, residents living in these facilities tend to be sicker and more functionally impaired. An increasing need for long-term care combined with shortages in the workforce and physical space in nursing homes shifts the burden of disease toward the community at large. Almost 20% of community-dwelling older adults suffer from a psychiatric disorder while approximately 28% of older adults have 3 or more chronic diseases. From 2007 to 2010, 89% of those aged 65 and older took at least one prescription drug in past 30 days, and 66.6% took 3 or more prescription drugs. Despite improvement in maintaining functional status, in 2010 23% of older adults had at least one basic action difficulty or complex activity limitation. Those persons most functionally impaired with loss of activities of daily living (ADLs) are increasing in proportion. With an aging population, oral health needs, which can affect quality of life and overall health, remain a concern.

As the United States increasingly ages, older adults have retained more teeth than ever before. In 1965, every other man or woman older than 65 years in the United States had no natural teeth. By contrast, in 2002 fewer than 25% of older adults were edentulous. However, older adults with a chronic condition such as diabetes, arthritis, cardiovascular disease, or chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, experienced a higher rate of tooth loss and edentulism than those without a condition. Furthermore, increasing numbers of elderly still necessitates fixed and removable complete dentures (CDs). Sixty-four percent of older adults have either moderate or severe periodontitis. Approximately 1 in 5 older adults have untreated coronal caries ; similarly, 1 in 5 report xerostomia. Twelve percent of adults age 60 years and older have root caries. The need for treatment exists.

In recognition of treatment needs, older adults continue to seek dental care. From 2000 to 2011, dental utilization among older adults increased from 38% to 42% (Medical Expenditure Panel Survey ). This trend is consistent with previous analyses of the same survey, which showed greater utilization among older adults than younger adults. In 2007, 92% of dentists report treating vulnerable elderly patients. In the same survey, dentists indicate a lack of information about managing patients with complex medical histories, xerostomia, and dementia. In the next sections, management of the treatment-planning process for older patients is discussed.

Goals of the treatment-planning process

Treatment planning is the culmination of a comprehensive diagnostic process that usually precedes routine treatment. A goal of treatment planning should be the development of a systematic means of action to eradicate dental disease, reestablish and preserve as much function as possible, and enhance quality of life. It should address the underlying disease process giving rise to signs and symptoms found on examination and elicited from patients. Treatment plans should also attend to patients’ chief complaints as quickly as possible, rely on individual needs, and prevent and manage tooth loss. Furthermore, treatment plans should communicate the role of caregivers in maintenance and care, account for realistic circumstances, be continuously informed, make dental appointments as comfortable as possible, and emphasize continued monitoring of oral health and a functional dentition. The most influential factors in comprehensive treatment planning are patients’ disease status, followed by patients’ requests, and lastly, patients’ ability to pay. The treatment-planning process facilitates diagnosis of disease(s) and results in a plan that accounts for patients’ interests and expectations, treats diagnosed problems, and provides a stepwise strategy for maintaining oral health.

Review of conventional treatment planning

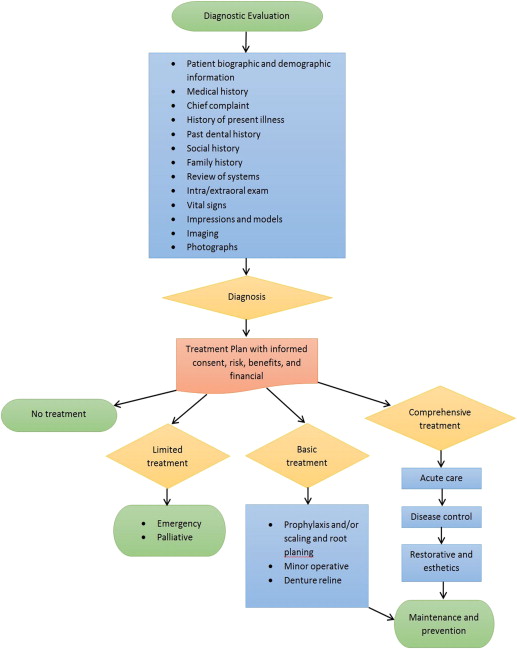

Treatment plans vary in the breadth of services required and the degree of comprehensiveness involved in treatment delivered. The simplest treatment plan consists of no treatment. On another level, limited treatment plans address only emergency and/or palliative care. Basic treatment plans are expanded in scope by providing for additional procedures such as scaling and root planing, denture relines, or minor operative interventions. Comprehensive treatment plans inherently address more complicated, multistep, sequenced procedures, which usually entail different disciplines such as endodontics and prosthodontics ( Fig. 2 ).

With regard to comprehensive treatment planning, treatment considerations are incorporated through several phases dynamically informed by patient desires. Comprehensive treatment, as outlined in the treatment plan, is accomplished over these phases: diagnostic evaluation phase, priority and acute phase, disease control phase, restorative phase subdivided into preprosthetic and definitive prosthetic, and maintenance and prevention phase.

Diagnosis of disease and resultant treatment plans culminate from a thorough diagnostic evaluation that assembles the following information: complete medical history, patient information and chief complaint, history of present illness, dental history, social history, family history, review of systems, intraoral/extraoral examination, laboratory results, vital signs, impressions and models, imaging such as radiographs, and photographs. Additional information is often retrieved by a consultation with the patient’s physician; the consultation may require follow-up conversations with multiple care providers in cases with a complicated medical history.

Acute issues of an emergent or palliative nature are immediately addressed. Treatment of acute pain exemplifies a pressing issue requiring immediate attention. After an emergency or palliative phase, a disease-control component manages any extended conditions such as initial periodontal treatment, caries control activities, and prevention activities. The restorative and aesthetics phase following disease control may be further subdivided into a preprosthetic phase and definitive prosthetic phase. Critical sequencing in preparation for final restorations is planned during this phase. The preprosthetic phase often entails advanced treatment in oral surgery, endodontics, orthodontics, periodontal surgery, and implant placement. The final prosthetic phase involves certain types of permanent operative restorations, fixed and removable final prostheses. Finally, in the maintenance and prevention phase, all treatment is reevaluated and the patient is placed on a maintenance schedule. An appropriate prevention plan for the time interval between recall examinations is also determined.

Models of geriatric dental treatment planning

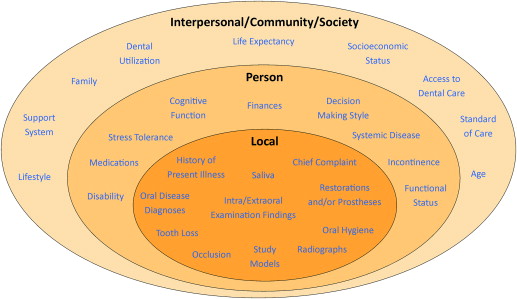

This section provides an overview of treatment-planning models that attempt to account for the myriad of considerations accompanying dental care for the elderly, and Fig. 3 presents a diagram summarizing of the factors presented in these models. A straightforward yet comprehensive approach to treatment planning for older adults uses the familiar mnemonic SOAP (Subjective findings, Objective findings, Assessment, and Plan). In geriatric patients, the subjective findings include additional information concerning functional status as described by the ability to carry out ADLs and instrumental activities of daily living. Otherwise, objective findings and resultant assessment develop in the usual fashion. Finally, the plan section details any treatment performed and delineates a comprehensive, sequenced treatment plan, which may or may not take into account modifying factors.

Another approach to treatment planning for older adults uses the easy to remember mnemonic OSCAR, which stands for Oral factors, Systemic factors, Capability, Autonomy, and Reality. The assessment should follow the order of the mnemonic. Oral factors take into consideration the current dentition and restorations, periodontium, oral hygiene and root caries, salivary secretions, tooth loss, mucosal tissues, removable prosthesis, and occlusion. Systemic factors encompass normal changes related to aging and comorbidity, effect of medications, and communication between the dentist and physician(s) in managing the geriatric dental patient with a medically compromised health status. Capability refers to attributes such as the ability to carry out ADLs, walk with or without assistance, and control incontinence. Autonomy relates to the patient’s ability to independently make health care decisions within the context of cognitive impairment stemming from a history of stroke, dementia, depression, or other conditions. Lastly, reality refers to financial issues and life expectancy.

The rational treatment model considers the influence of modifying factors on primary factors, which in turn alter the biofilm and, consequently, the development of oral diseases and conditions. Modifying factors such as lifestyle, socioeconomic status, medications, cognition, disability, and medical and dental history alter the balance of diet, saliva, and genetics, and affects chemotherapeutics and oral hygiene. This model, adapted from a caries risk model, explains how etiologic factors affect the development of caries, periodontal disease, tooth loss, and mucosal lesions. Furthermore, risks and benefits of treatment also influence whether no treatment, emergency care, limited treatment, or comprehensive care is planned. In addition, an example of the rational treatment model depicts the utility of a decision tree in treatment planning for dentate adults. The patient’s desires, expectations, dental needs, quality-of-life expectations, stress tolerance, financial status, and oral hygiene capacity, along with the dentist’s experience and skill level, direct the treatment-planning process.

Another model uses a clinical reasoning sequence in decision making and resolution of dental problems. In the model, 3 action sequences are presented in resolving dental problems: (1) determine the cause, (2) choose an action, and (3) implement the plan. To determine cause, the problem must be defined, other possible causes considered, and possible causes tested. To help choose an action, goals in consultation with the patient must be established, alternatives examined, and adverse consequences considered. Finally, implementation of the plan involves anticipating potential problems, taking preventive actions, and setting up contingency plans. This systematic approach can be successful if the steps in the action sequences are effective.

Another approach addresses complexity and uncertainty in treatment planning in elderly patients, and provides a basis for prioritizing and weighing factors affecting the treatment-planning process. More than 20 factors contribute to the process. Some important factors include: reliance on biological age rather than chronologic age; consideration of the useful life of dental interventions such as fillings and prosthetics in the context of life expectancy for older adults; and reconciliation of expectations between the patient, other involved parties, and the dentist through effective communication. To address uncertainties inherent to treatment planning, clear decisions should be made and treatment progress monitored. Careful documentation from evaluation to implementation protects from uncertainty.

Mulligan and Vanderlinde present a geriatric care model that is intended to account for the factors precipitating successful treatment in any setting. The model depicts the interplay between 4 broad domains: dental/oral, medical, psychosocial, and behavioral. Examination findings, influence of systemic disease, physician consult, dental specialty referral, treatment plan modifications, and selection of appropriate treatment options constitute the factors within the dental/oral category. Suggested medical factors to consider include: systemic conditions; medications, including adverse effects and drug-drug interactions; laboratory values; special issues; and medical referral. Psychosocial factors influencing treatment plan include: informal assessment; basis of functioning such as cognition, recognition, reasoning, and commitment; and support system from the societal to the personal. Among behavioral factors, the areas of consideration are: decision-making style; ability to cooperate with treatment; sedation involving feasibility and need; understanding of one’s own limitations; need for personal assistance; home-care capability; and adherence potential. This model guides the clinician in attenuating psychosocial, medical, and behavioral barriers.

Finally, a more specific approach to treatment planning addresses dementia and its role in planning. In the early stage of dementia, when changes in cognitive function are minimal, changes to the treatment-planning process are minimal as well. However, if there is an accompanying degenerative disease diagnosis such as Alzheimer disease, the treatment plan should be designed to anticipate future loss of cognitive function, include aggressive prevention, and restore function with celerity. Treatment plans for middle and late stages of dementia may require considerations such as modifying appointment length, using sedation, and increasing the frequency of recalls. In the middle stages of dementia, it is suggested that limited treatment plans are designed with minimal changes, and should include aggressive prevention along with communication of prevention strategies with caregivers. Treatment of those at advanced and terminal stages may be basic, with palliative and emergency care aimed at maintaining the dentition. As described, many considerations are factored into treatment planning for the older adult. Nonetheless, throughout the treatment-planning process the patient’s desires continually influence clinical decision making. However, communication between the dentist and an older patient can be complicated by competency and informed consent issues.

Decision-making capacity, competency, and informed consent

Before any dental examination, the clinician must obtain a valid consent to treat or not treat. In general, informed consent requires a disclosure of the relevant risks of, benefits of, and alternatives to treatment that potentially affect the patient’s decision on the treatment. However, proper disclosure by the clinician alone is insufficient to obtaining a valid consent. The patient must also possess decision-making capacity as defined by ability to comprehend, appreciate, and reason the contingencies of treatment or no treatment ; the ability to weigh the risks and benefits of treatment, no treatment, and alternatives; and the ability to communicate his or her choices. In some instances, especially in the elderly, determination of capacity may be unclear and subject to bias. The elderly with dementia and/or psychiatric illness, nursing home residents, and hospitalized elderly all have increased risk for reduced consent capacity. In most cases when a patient is determined to lack capacity, the clinician assigns a health care proxy to consent for that patient. Dentists are legally bound by the same process and standards as physicians and other health care professionals in securing informed consent. Therefore, dentists should know and comply with the legal obligation regarding capacity and informed consent for the state in which they practice. The evaluation for capacity to consent for treatment should be a fluid process to be evaluated at each treatment decision. The patient should have self-determination of as much of their treatment as possible.

Although decision-making capacity and competency are similar; they are not synonymous. The legal determination of patient competency describes the ability of the patient to make informed decisions. However, patient competency differs in scope, determination, and purpose. Lack of capacity does not preclude a patient from making any decisions. Each decision varies in risk, benefits, and complexities, and should be independently assessed. When appropriate, patients should be empowered to make their own decisions. However, competency, formally determined by a court of law, concerns the individual’s mental capacity to make autonomous decisions in general. At the time a person is determined incompetent, a court appoints a guardian who acts as a surrogate decision maker. In addition to health care decisions, the guardian handles decisions regarding contracts, finances, and other personal affairs. In this case, obtaining consent is straightforward; the guardian provides informed consent. A case is now presented that emphasizes many of the factors highlighted in this discussion of treatment-planning considerations.

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses