Key points

- •

There are too many variables to permit a totally scientific approach to a comparative evaluation of the different facelift techniques.

- •

Advocates of the deep plane technique have the impression that the procedure produces better and longer-lasting results, although this has not been scientifically proved and continues to be disputed by many surgeons.

- •

In our experience the biplane facelift has increased aesthetics and longevity with limited morbidity.

Rhytidectomy is from the Ancient Greek ῥυτίς (rhytis) “wrinkle” + ἐκτομή (ektome) “excision,” or the surgical removal of wrinkles. Historical evidence of rhytidectomy dates back to Höllander in 1901 in Berlin. An elderly female Polish aristocrat asked him to “lift her cheeks and corners of the mouth.” After much debate he finally proceeded to excise an elliptical piece of skin around the ears.

In 1919, Passot published one of the first known papers on facelifting, which was mainly on elevating and redraping of the facial skin. The first 60 years of facelift surgery was limited to a subcutaneous dissection. However, throughout the first half of the century surgeons were performing more extensive cervicofacial skin undermining. In the 1950s in the United States, Mayer and Swanker were early proponents of the classic wide skin undermining facelift.

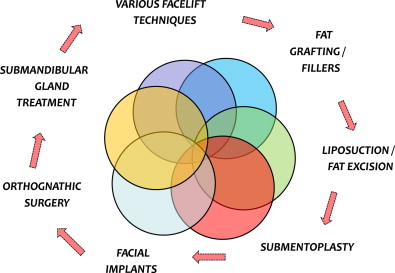

In the late 1960s and early 1970s, Mitz and Peyronie described the superficial musculoaponeurotic system (SMAS) technique of facelifting. In 1968, Skoog developed a flap to elevate the platysma muscle of the neck and lower face without undermining the skin. Skoog eventually published his work in 1974. Skoog described his “deep plane” facelift, which emphasized the presence of an interconnected “skin-fat-musculofacial unit” that if elevated as a unit would improve facelift results. The SMAS technique soon emerged as the leading facelift technique. Despite SMAS manipulation being common, multiple options or procedures need to be addressed for maximum results ( Fig. 1 ).

The manipulation of the SMAS plane has become the standard for most cosmetic surgeons. Numerous authors have reported variations of the SMAS facelifting technique, but the only real modification has been the extent of undermining and the direction and vector of pull. Elevation of this musculofascial plane is a key component of the biplane facelift.

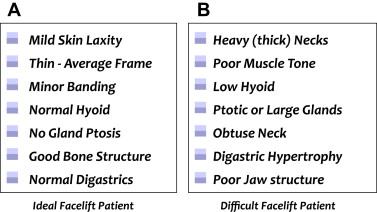

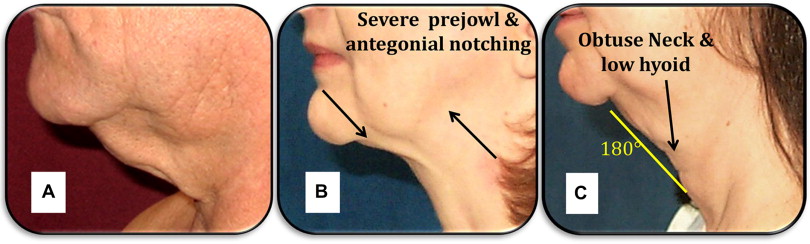

Aesthetic facial surgery is intended to rejuvenate the cervicofacial contour. Recognizing the elements of an aging face and neck is a prerequisite to planning any procedure. Common stigmata of facial aging include ptotic malar pads, heavy nasolabial folds, nasojugal creases, marionette lines, jowls, geniomandibular grooving, cheek and neck skin laxity, platysmal banding, lateral orbital wrinkling, submental lipodystrophy, and salivary gland ptosis ( Fig. 2 ). It is critical to identify easy versus difficult problems to correct ( Fig. 3 ).

Facelift surgery for a thin individual with great bone structure typically is less challenging and improvement can be achieved with almost any type of facelift ( Fig. 4 ). Recognizing the more difficult patient with a heavy or obtuse neck, poor bone structure, extreme laxity, poor muscle tone, or a low hyoid is essential for avoiding an unhappy patient ( Fig. 5 ).

Biplane facelift

The biplane facelift is based on principles that improve and increase aesthetics and the longevity of the procedure, with limited morbidity. Changes in the deeper musculofascial plane are most responsible for the pronounced effects of facial aging. The biplane facelift allows for the precise elevation and rotation of this deep musculofascial plane. The biplane facelift can give the patient a natural-appearing rejuvenation along with a very long-lasting improvement in the patient’s cheek, jowl, and cervicofascial regions.

The name “biplane” refers to a long, subcutaneous flap developed sharply to limit damage to the underlying subdermal fat and vascularized dermis ( Fig. 6 ). The second or biplane portion of the facelift is elevated separately as a musculofascial deep flap elevation. It begins from the zygomatic arch and extends inferiorly along the posterior platysmal edge down into the neck ( Fig. 7 ). Finally, the other additional portion of the biplane is carried out in the submental area. The submentoplasty is also a biplane lift and is considered an integral part of this lower facelift to maximize the chin-neck angle ( Fig. 8 ). The platysma is elevated and the opportunistic portion of this technique is based on the patient’s anatomy at the time of surgery.

Biplane facelift

The biplane facelift is based on principles that improve and increase aesthetics and the longevity of the procedure, with limited morbidity. Changes in the deeper musculofascial plane are most responsible for the pronounced effects of facial aging. The biplane facelift allows for the precise elevation and rotation of this deep musculofascial plane. The biplane facelift can give the patient a natural-appearing rejuvenation along with a very long-lasting improvement in the patient’s cheek, jowl, and cervicofascial regions.

The name “biplane” refers to a long, subcutaneous flap developed sharply to limit damage to the underlying subdermal fat and vascularized dermis ( Fig. 6 ). The second or biplane portion of the facelift is elevated separately as a musculofascial deep flap elevation. It begins from the zygomatic arch and extends inferiorly along the posterior platysmal edge down into the neck ( Fig. 7 ). Finally, the other additional portion of the biplane is carried out in the submental area. The submentoplasty is also a biplane lift and is considered an integral part of this lower facelift to maximize the chin-neck angle ( Fig. 8 ). The platysma is elevated and the opportunistic portion of this technique is based on the patient’s anatomy at the time of surgery.

Clinical anatomy

Detailed knowledge of the surgical facial anatomy in conjunction with the pathology to be corrected is necessary for correct surgical planning and preoperative markings. The patient should be examined in a brightly lit room. The patient is appraised while upright for accurate analysis of the anatomy. There are five important anatomic levels in the face and neck: (1) skin, (2) subcutaneous fat, (3) the SMAS/muscle layer, (4) deep fascia, and (5) facial nerve.

Skin

Skin changes in appearance and characteristic with aging. The aging process is accelerated by sunlight. This process is called dermatohelisosis, solar elastosis, or photoaging.

Subcutaneous tissues

This is a relatively safe plane for dissection. This layer contains fine ligaments passing from the underlying SMAS to the overlying dermis of the skin. These ligaments transmit mimetic movements into facial expressions but also contribute to facial lines and wrinkles.

SMAS/muscle layer

Below the skin and subcutaneous tissues is the SMAS/muscle layer. This layer is a continuum from the neck to the scalp. The platysma in the neck is the most inferior portion of the SMAS, which continues in the face over the parotid. Above the zygoma, the SMAS is contiguous with the frontalis muscle and the temporoparietal fascia. The temporoparietal fascia blends into the galea in the scalp.

Fascial layer

Between the SMAS and the facial nerve is a deeper fascial layer. In the neck this layer is termed the “cervical fascia.” Over the parotid it is called the parotideomasseteric fascia. In the upper third of the face, the layer becomes the innominate fascia that blends into the subgaleal fascia over the scalp.

Facial nerve

The facial nerve trunk emerges from the stylomastoid foramen to provide motor innervations to 20 paired muscles of facial expression. The motor portion of the facial nerve divides into five major branches and care must be taken to avoid injury particularly during deep plane elevation over the parotid region ( Fig. 9 ). The branches travel just deep to the cervical-parotideomasseteric fascia to innervate all the muscles of facial expression from their deep surface with three exceptions: (1) the mentalis, (2) the buccinators, and (3) the levator anguli oris. These muscles lie deep to the facial nerve and are therefore innervated on their superficial surfaces.

Parotid and submandibular salivary glands

A total of 80% of the parotid gland lies between the mastoid process and the posterior border of the mandible. About 20% of the gland extends convexly forward over the masseter muscle occasionally as far as the zygomaticus major. The buccal branch of the facial nerve parallels the parotid duct.

Submandibular glands lie in the submandibular triangles formed by the anterior and posterior bellies of the digastrics muscles and the inferior border of the mandible. The marginal mandibular branch of the facial nerve courses superficial to the submandibular gland and deep to the platysma. Ptotic or large submandibular glands should be addressed during the submentoplasty and in some cases need to be partially excised to have a smooth texture to the skin in this region ( Fig. 10 ).