This article discusses the importance of having a strong vision and culture within the context of emergency preparedness in a home-base state. It proposes a broader vision of public health, one that places public health emergency preparedness and response squarely at the center of the public health mission as a core function. It also lays out work currently underway and the future direction for maximizing the value of response-oriented partnerships at the state and local levels in the Evergreen State. The role of health care professionals and dental providers is specified in more detail. Broadening the public health vision requires recognition of the importance of multisectorial partnerships and their response potential, including the potential roles of all health-related professions and the development of systems to use that potential effectively.

September 11, 2001 and Hurricane Katrina are experiences that touched all Americans. These events brought the need for effective emergency response to the forefront and exemplified what it takes to succeed and how easy it can be to fail.

“Today there is a national consensus that we must be better prepared to respond to events like Hurricane Katrina. While we have constructed a system that effectively handles the demands of routine, limited natural and man-made disasters, our system clearly has structural flaws for addressing catastrophic incidents” .

Sharing a vision and spreading a culture of emergency preparedness to all levels of society is considered a national need and obsession. Obstacles exist, however, on the road to making it happen, some of which are inherent to human nature. For example, most human beings tend to forget the initial feelings of helplessness and frustration that a catastrophic event brings, giving place to more passive feelings of sorrow and remembrances. For people who face the issue and want to become active members of preparedness efforts, it can be overwhelming to decide how to do it, and inertia eventually kicks in. These are common coping mechanisms, not only of single individuals but also of communities and organizations. For emergency preparedness to be successful, anything less than an active approach allows history to repeat itself. For this reason, a powerful vision and a strong culture become essential tools for engaging partners and communities into the emergency preparedness movement. An overall challenge requires an overall response.

“…But we as a Nation—Federal, State, and local governments; the private sector; as well as communities and individual citizens—have not developed a shared vision of or commitment to preparedness: what we must do to prevent (when possible), protect against, respond to, and recover from the next catastrophe. Without a shared vision that is acted upon by all levels of our Nation and encompasses the full range of our preparedness and response capabilities, we will not achieve a truly transformational national state of preparedness. There are two immediate priorities for this transformation or change process: 1) to define (a vision for) and implement a comprehensive National Preparedness System; and 2) to foster a new, robust Culture of Preparedness” .

Defining vision and culture

A vision is an attempt to articulate a desired future. It identifies the end state we are seeking to achieve and how we plan to get there. It identifies core values and beliefs, is idealistic, inspiring, desirable, future oriented, bold and ambitious, unique, well articulated, and easily understood, and it represents broad and overarching goals. A well-articulated vision sets the horizon for the work to be done. Culture is a more elusive concept to define. Historically, cultures have emerged around a proposal for a vision that is embraced and held in sacred status by a collective. A culture can be recognized as the body and codification of symbols through which a community engages the projects of world building and meaning making. It provides the framework for processing information, developing knowledge, seeking awareness, and forming identity and relationships.

“National preparedness involves a continuous cycle of activity to develop the elements (eg, plans, procedures, policies, training, and equipment) necessary to maximize the capability to prevent, protect against, respond to, and recover from domestic incidents, especially major events that require coordination among an appropriate combination of Federal, State, local, tribal, private sector, and non governmental entities, with the goal of minimizing the impact on lives, property, and the economy” .

The challenge ahead is how to share such vision successfully at the state and local levels, within public health, other government, and nonprofit and private sectors and how to do it in a way that not only is compatible with and attractive to the local reality but also formulates a strengthened and more contemporary public health culture.

The growing role of public health

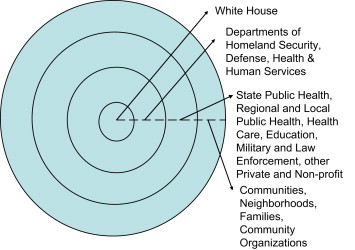

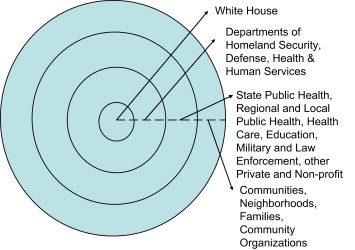

Although the emergency preparedness movement is multisectorial ( Fig. 1 ), public health agencies are viewed as one of the cornerstones of emergency preparedness programs. This role has evolved historically more out of necessity than appropriate planning. Already in 1988, the Institute of Medicine (IOM) published a scathing report entitled “The Future of Public Health” . This study was undertaken to “address a growing perception among the IOM membership and others concerned with the health of the public that this nation has lost sight of its public health goals and allowed the system of public health activities to fall in disarray.”

At a time when the traditional problems that gave birth to public health seemed to have been conquered by the escalating successes of science and not a few pharmaceutical “miracles,” the IOM turned its attention to public health as a social service field and analyzed its deficiencies as such. This IOM report was visionary and established organizational and programmatic models for public health that were considered at the time contemporary and innovative in the highest sense of these words. The IOM report even went so far as to note the need to successfully counter continuing and emerging public health threats. Its listing of such threats, however, was limited by the times and unable to foretell events of the magnitude of those that occurred on September 11, 2001 and thereafter, including the 2006 Gulf storms, the looming threat of a deadly influenza pandemic, and the emergence of drug-resistant diseases such as tuberculosis.

From the limits of its vantage point, IOM members forged a vision for public health based on the government’s mission of ensuring social conditions in which people can be healthy, which still guides public health activities. The core functions under that mission were listed as “assessment, policy development, and assurance.” The limits of this awareness in effect sealed public health’s retreat from the trenches into the sanctuary of social programs based on prevention activities. At no time did the IOM membership recognize that unforeseen future circumstances would propel public health back into the trenches, revealing more clearly than ever before its archetypical function as an emergency response capacity during emergencies and disasters of every ilk.

A second report from IOM, “The Future of the Public’s Health in the 21st Century,” which was released in 2002, expanded the initial framework . More keenly focused on the largess of future challenges rather than the successes of the field, the report strongly propounded on the need for and value of multisectorial engagement in overcoming them. In a remarkable post-9/11 state of awareness, IOM stated that public health alone (ie, government and its traditional partners in that endeavor) were no longer sufficient to confront the current reality of what it would take to promote and protect the health of the population in the twenty-first century. More than ever, these suggestions hold true for the field of public health preparedness and response.

The report made only passing reference to the challenges of getting public health ready to confront a large complex and fluid emergency, such as pandemic flu, although it did agree that among six paramount action areas two would be to strengthen governmental public health infrastructure and develop a multisectorial public health system based on more robust partnerships with the public health system, the community, the health care delivery system, employers and business, the media, and academia.

Overall federal, state, and local public health efforts

After the events of September 11, 2001, the Bush administration communicated to the public health community a sense of urgency to plan for the likelihood of a terrorist attack involving weaponized smallpox virus. The underlying vision was not clear then, and even currently there is still scant evidence of its intent. Although the public health community remained skeptical overall, health departments around the nation set to work on the challenge of emergency preparedness and response planning around this potential hazard. Federal funding was allocated to states with strict requirements for response plans, along with hard and fast deadlines bordering on the unreasonable.

For individuals who were involved in these efforts, it soon became evident that public health peers, other government functionaries, and potential partners whose primary preoccupation was to administer public health programs under the faithful model suggested by IOM in 1988 held a different set of priorities. The threat, many argued, was not credible enough and was largely considered political hype. A generalized attitude of guarded collaboration sent a clear message to emergency preparedness professionals that the public health community’s broad belief was that “this too shall pass” and public health would get back to its business of running prevention and regulatory programs soon enough. Many states and local health departments initially refused to change their organizational structures to accommodate preparedness programs, placing them as an add-on or as a special and temporary function—like a burden on a system that refused to accept that the world had changed—to accept funds that would help rebuild an otherwise neglected public health infrastructure under the guise of emergency preparedness.

The willingness of the federal government to provide copious funding for emergency preparedness to states and local jurisdictions, public health leaders argued, was precisely that: an opportunity to capitalize on and get public health on the political radar screen so that the “real” work of public health might be known by all and resourced as deserved. In effect, the national vision for public health as the social service field of the 1980s remained basically unchanged and unable to accommodate the awareness that a new era had begun with the new millennium. For several reasons, the nation, if not the world, had to function in an environment of quickly evolving threats, any of which could overwhelm existing response systems and their current levels of preparedness at any given time, and at the time public health suffered from a large scotoma about the full implications for its role in that environment.

In many cases, the public health community continues to struggle with that vision impairment. Public health program managers and staff have difficulty seeing the relevance of emergency preparedness to their scope of work; collaboration is limited by competing priorities and, in some instances, is contentious. Training and cross-training of public health professionals for the sake of creating a robust system of response based on redundancies and staffing schemes with bench strength and depth has been painfully slow. The involvement of external partners to bolster surge, supplemental capacity also has been paused, particularly outside of the more traditional cadre of players, and it remains distant from constituting a “system.”

Despite these difficulties, much and laudable work has been accomplished at the federal, state, and local levels in the span of 5 years. Beyond any argument, the national public health system continues to change in significant ways and is better prepared than ever to understand its potential challenges.

The growing role of public health

Although the emergency preparedness movement is multisectorial ( Fig. 1 ), public health agencies are viewed as one of the cornerstones of emergency preparedness programs. This role has evolved historically more out of necessity than appropriate planning. Already in 1988, the Institute of Medicine (IOM) published a scathing report entitled “The Future of Public Health” . This study was undertaken to “address a growing perception among the IOM membership and others concerned with the health of the public that this nation has lost sight of its public health goals and allowed the system of public health activities to fall in disarray.”

At a time when the traditional problems that gave birth to public health seemed to have been conquered by the escalating successes of science and not a few pharmaceutical “miracles,” the IOM turned its attention to public health as a social service field and analyzed its deficiencies as such. This IOM report was visionary and established organizational and programmatic models for public health that were considered at the time contemporary and innovative in the highest sense of these words. The IOM report even went so far as to note the need to successfully counter continuing and emerging public health threats. Its listing of such threats, however, was limited by the times and unable to foretell events of the magnitude of those that occurred on September 11, 2001 and thereafter, including the 2006 Gulf storms, the looming threat of a deadly influenza pandemic, and the emergence of drug-resistant diseases such as tuberculosis.

From the limits of its vantage point, IOM members forged a vision for public health based on the government’s mission of ensuring social conditions in which people can be healthy, which still guides public health activities. The core functions under that mission were listed as “assessment, policy development, and assurance.” The limits of this awareness in effect sealed public health’s retreat from the trenches into the sanctuary of social programs based on prevention activities. At no time did the IOM membership recognize that unforeseen future circumstances would propel public health back into the trenches, revealing more clearly than ever before its archetypical function as an emergency response capacity during emergencies and disasters of every ilk.

A second report from IOM, “The Future of the Public’s Health in the 21st Century,” which was released in 2002, expanded the initial framework . More keenly focused on the largess of future challenges rather than the successes of the field, the report strongly propounded on the need for and value of multisectorial engagement in overcoming them. In a remarkable post-9/11 state of awareness, IOM stated that public health alone (ie, government and its traditional partners in that endeavor) were no longer sufficient to confront the current reality of what it would take to promote and protect the health of the population in the twenty-first century. More than ever, these suggestions hold true for the field of public health preparedness and response.

The report made only passing reference to the challenges of getting public health ready to confront a large complex and fluid emergency, such as pandemic flu, although it did agree that among six paramount action areas two would be to strengthen governmental public health infrastructure and develop a multisectorial public health system based on more robust partnerships with the public health system, the community, the health care delivery system, employers and business, the media, and academia.

Overall federal, state, and local public health efforts

After the events of September 11, 2001, the Bush administration communicated to the public health community a sense of urgency to plan for the likelihood of a terrorist attack involving weaponized smallpox virus. The underlying vision was not clear then, and even currently there is still scant evidence of its intent. Although the public health community remained skeptical overall, health departments around the nation set to work on the challenge of emergency preparedness and response planning around this potential hazard. Federal funding was allocated to states with strict requirements for response plans, along with hard and fast deadlines bordering on the unreasonable.

For individuals who were involved in these efforts, it soon became evident that public health peers, other government functionaries, and potential partners whose primary preoccupation was to administer public health programs under the faithful model suggested by IOM in 1988 held a different set of priorities. The threat, many argued, was not credible enough and was largely considered political hype. A generalized attitude of guarded collaboration sent a clear message to emergency preparedness professionals that the public health community’s broad belief was that “this too shall pass” and public health would get back to its business of running prevention and regulatory programs soon enough. Many states and local health departments initially refused to change their organizational structures to accommodate preparedness programs, placing them as an add-on or as a special and temporary function—like a burden on a system that refused to accept that the world had changed—to accept funds that would help rebuild an otherwise neglected public health infrastructure under the guise of emergency preparedness.

The willingness of the federal government to provide copious funding for emergency preparedness to states and local jurisdictions, public health leaders argued, was precisely that: an opportunity to capitalize on and get public health on the political radar screen so that the “real” work of public health might be known by all and resourced as deserved. In effect, the national vision for public health as the social service field of the 1980s remained basically unchanged and unable to accommodate the awareness that a new era had begun with the new millennium. For several reasons, the nation, if not the world, had to function in an environment of quickly evolving threats, any of which could overwhelm existing response systems and their current levels of preparedness at any given time, and at the time public health suffered from a large scotoma about the full implications for its role in that environment.

In many cases, the public health community continues to struggle with that vision impairment. Public health program managers and staff have difficulty seeing the relevance of emergency preparedness to their scope of work; collaboration is limited by competing priorities and, in some instances, is contentious. Training and cross-training of public health professionals for the sake of creating a robust system of response based on redundancies and staffing schemes with bench strength and depth has been painfully slow. The involvement of external partners to bolster surge, supplemental capacity also has been paused, particularly outside of the more traditional cadre of players, and it remains distant from constituting a “system.”

Despite these difficulties, much and laudable work has been accomplished at the federal, state, and local levels in the span of 5 years. Beyond any argument, the national public health system continues to change in significant ways and is better prepared than ever to understand its potential challenges.

The Washington State scenario

The Evergreen State has been in the process of developing its public health emergency preparedness and response program since 2002 . A brief analysis of this program follows based on Kotter’s framework on successful change management.

Establishing a sense of urgency: state’s threat assessment

There is little room for doubt that Washington State is territory primed to experience the potentially catastrophic effects of natural disasters and perhaps other types of emergencies with a public health dimension . Washington is a land of telluric forces—natural, social, political, economic—that create conditions favorable to disasters and other emergencies involving massive losses and casualties, and with a potential to overwhelm the capacity of the health system to deal with them at any given time.

In Washington’s modern history hardly a year has gone by when there was not either a major federal disaster or emergency declaration or a significant fire management assistance declaration. Besides storms, flooding, tidal surges, and landslides, in the last 40 years the state has experienced a volcano eruption of global scale (Mount Saint Helen), four major earthquakes in modern times (1872 in the Cascade Mountains, 1949 in Olympia, 1965 in Bremerton, and 2001 in Olympia), a major drought, and several catastrophic wildfires. More similar events are prognosticated and likely to continue to occur with some increase in frequency, larger impact, or both.

Adding to Washington’s proclivity for natural disasters is the country’s current political positioning in a global environment of growing discontent with US foreign policy. These circumstances have laid a context for multiple threats, thwarted attempts against visible targets, and actual attacks against the nation. Within Washington’s boundaries are found ports of entry with international prominence and high traffic volume and target value. The city of Seattle, the state’s financial center, continues to increase its gravitational pull on the national and international tourism industry, global financial markets, and international commerce of every sort partly because of its highly visible industries, aesthetic beauty, benign climate, and strategic location—features that also make the city highly vulnerable. When added up, these factors significantly elevate Washington’s threat vulnerability coefficient regarding intentional acts of disruption and attacks of every sort (eg, chemical, biologic, radioactive).

A read of the evolving threat environment discloses that the occurrence of emerging and drug-resistant diseases, vector borne/zoonotic diseases, and other public health threats tied to environmental factors is on the rise around the world. Climate change, increased global commerce, demographic explosion, changes in species migration patterns, mass food production, and processing strategies are creating fertile conditions for the threat of infectious and communicable diseases to increase significantly in the foreseeable future. Many of these disease outbreaks tend to originate in densely populated and poorly sanitized third world countries with which Washington maintains prolific commercial ties. During the 2004 SARS outbreaks, the Washington public health community had to respond to one such threat and is currently undergoing intense preparations against a potential outbreak of pandemic influenza given the state’s role as a portal to the high volume markets of the Far East. Sea-Tac Airport also is the designated diversion airport for the West Coast to where any flight transporting refugees, criminal acts in progress, or ill and diseased passengers will be directed.

There is no way of knowing which, if any, of these threats will take place in Washington in the near future. There is no doubt, however, that the potential for something to happen on a scale that would impose a significant deployment of available health-related resources is present at any time. Such a scenario would require the capacity to maximize the potential of the public health system, including imaginative use of alternative or supplemental resources to cover any surge demands in current capacity. It also challenges the Washington public health community to engage the project of broadening its vision and building a culture of public health readiness without delay.

The effective deployment of a system for surge capacity under emergency conditions demands that a great deal of infrastructure development and preparedness measures be in place before the occurrence of an event. To be sure, a sufficient canon of legislation exists in Washington to provide the Governor of the state and the Secretary of Health with enough authority to press into service any professional with a modicum of medical training and basic health care sense. It is not an unlikely picture to imagine, for example, dental professionals giving shots, operating ventilators, leading triage units, assessing vital signs, and even performing surgery as might be required by the situation and as their training allows.

Forming a powerful guiding coalition of partners: the heightened importance of partnerships in a home rule state

Washington State’s home rule tradition

Washington State is known for its numerous coalitions and partnerships involving state and local governments and communities, especially those related to public health issues. This is a consequence of the strong expression of the “home rule” tradition in our state, which favors decentralized government and has been in place since 1948 (Article XI, § 4 of the Washington State constitution)

The history of the State of Washington has been shaped by a combination of great events and movements, the settlement patterns described by a diverse population as communities formed across a geographically diverse territory, and the ways in which those communities chose to deal with historic events based on their local experience of place

The coming of the railroad, populism, prohibition, municipal tax reform, public power, the Great Depression, property tax limitations, federal government assistance, and the great wars were historical benchmarks in the dialog that shaped the state’s home rule tradition. Of no lesser significance was the physical and cultural isolation of early settlements along the lines of economic interest, ethnicities, and the exploitation of natural resources. Above all, the fiercely independent frontier spirit of pioneer Washingtonians helped determine how the political dialog on the issues evolved around values of self-determination, community, and participatory civil society.

Although not a true “home rule” in the legal sense, the strong culture of local governance and control in Washington is defined by two overarching characteristics: insistence on local option and control, including how state policy is shaped and implemented, and the unique relationship between local governance authorities, including special purpose districts authorized to provide specific services to the population, such as is the case of local health jurisdictions.

Over time, these relationships evolved to become more functional according to the issues of the time while all along reaffirming the underpinnings of the tradition of local control. Currently, these relationships are mostly defined by the prominent effects of growing fiscal pressures, population growth, environmental constraints of various kinds, and the need for equitable distribution and availability of services across the state. Inasmuch as Washingtonians tend to like local solutions to their problems, they want to be in charge of them and they want them to work well, perhaps better than those of their neighbors. Although through these efforts local governance relationships and traditions have evolved through time, however, they have not been able to keep pace with the speed and complexity of change in Washington, particularly in the last 60 years since World War II.

This is certainly the case in terms of the advent of a domestic security culture largely based on public health threats and concerns arising from the events of September 11, 2001, threats that—should they become reality—would be completely indifferent to geopolitical boundaries and the types of local concerns that dictate political protocol and policy development and implementation in Washington territory. For certain, these are threats whose potential is vastly more complex and exacting than the governance system’s current design might be able to effectively deal with.

The public health perspective for how to engage the requisite preparations to respond to an attack to the homeland or, more currently, a pandemic event has been, predictably, to improvise on the existing system of local authority while causing minimal disruption of local politics and local-to-local and state-to-local governance relationships. The implications of these decisions for public health are significant and began in 2002 with the challenges involved in negotiating an adequate and equitable funding formula for 35 local health jurisdictions with variegated needs, challenges, threat vulnerabilities, and capabilities. Advantageously, the system that emerged, rightly or not, minimized the role of the state as a responder and placed the brunt of the responsibility on local jurisdictions.

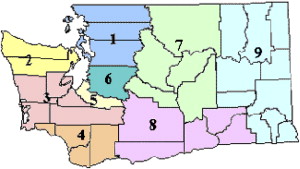

The funding requirements for the state included ensuring a coordinated system of preparedness and response across jurisdictions based on such features as articulated plans, mutual aid, shared capacities, interoperable communications, coordinated risk management, and training standards. To fulfill its responsibilities, the state, in partnership with local health officials, instituted an extra-official reorganization of local health jurisdictions into nine “Public Health Emergency Planning Regions” ( Fig. 2 ) responsible for the coordination of regional preparedness and response plans based on local plans and for the fiscal management of pass-through federal funds . So far this system has sufficed for the timely production of the deliverables tied to that funding—if not for effective planning—and recently Washington was evaluated by Trust in America’s Health, with high scores in preparedness for bioterrorism, pandemic flu, and health disasters on that basis .