Armamentarium

|

History of the Procedure

Bone grafting of the cleft maxilla was first described in the early 1900s ; however, the technique did not gain popularity until the 1950s, when Auxhausen challenged the maxillofacial surgical community by stating that obtaining bony continuity between the premaxilla and lateral segments was the final challenge facing cleft surgeons. Patients who had not undergone bone grafting experienced oronasal fistulas recalcitrant to soft tissue closure, periodontal deterioration of teeth adjacent to the cleft, persistent stigmata of cleft lip and palate attributable to insufficient bony support for the lip and nasal base, and challenging prosthetic rehabilitation that was prone to failure. Early responses to Auxhausen’s challenge focused on primary bone grafting as developed by Schmid. As experience with the technique grew, reports emerged describing significant adverse effects on midfacial growth; although a few centers have continued to perform bone grafting in infants, most centers worldwide have abandoned the procedure.

Skoog introduced the concept of gingivoperiosteoplasty in the mid-1960s and demonstrated success at forming a bone bridge across the cleft towards the nasal side with soft tissue reconstruction only. Presurgical orthopedic devices, ranging from the pin-retained Latham appliance to soft tissue–borne nasoalveolar molding appliances, were developed in an effort to align cleft segments so that gingivoperiosteoplasty could be performed with less subperiosteal dissection and presumably fewer negative effects on growth. Unfortunately, even when successful in creating bone, these grafts provide insufficient support for erupting dentition in the majority of patients. Consequently, secondary grafting procedures are frequently required, and the specter of negative effects on growth remains.

In the 1970s Boyne and Sands introduced secondary bone grafting, or grafting during the mixed dentition. Their proposal was based on the concept that maxillary growth was 80% completed by 8 years of age; therefore, interventions after that time would lead to minimal growth disturbance but would still provide the benefits touted by advocates of primary grafting. Because the goals of maxillary construction are most comprehensively and predictably met with this technique, bone graft construction at a developmentally appropriate time during the mixed dentition remains the procedure of choice in most centers.

The best results were reported when grafts were placed during the mixed dentition and before cuspid eruption; the success rate is greater than 90% when this timing is used. Initially, survival of the canine was the primary dental focus after grafting. Now, however, optimal timing is based on evaluation of all salvageable permanent teeth adjacent to the cleft, including not only the canine, but also the lateral incisor. Grafting is ideally performed when two thirds of root development is complete for the tooth in question. This degree of root formation allows eruption of the tooth through the graft site in a timely manner, stimulating the graft and enhancing success. In addition, this should allow grafting to precede entry of the crown of the tooth into the cleft because any graft placed adjacent to an erupted crown will be lost, compromising the final result.

Despite the description of many bone sources for secondary bone grafting of the cleft maxilla, including calvarium, mandibular symphysis, rib, tibia, allogeneic bone, and bone morphogenetic protein–2 (BMP-2), cancellous bone from the ilium remains the gold standard.

History of the Procedure

Bone grafting of the cleft maxilla was first described in the early 1900s ; however, the technique did not gain popularity until the 1950s, when Auxhausen challenged the maxillofacial surgical community by stating that obtaining bony continuity between the premaxilla and lateral segments was the final challenge facing cleft surgeons. Patients who had not undergone bone grafting experienced oronasal fistulas recalcitrant to soft tissue closure, periodontal deterioration of teeth adjacent to the cleft, persistent stigmata of cleft lip and palate attributable to insufficient bony support for the lip and nasal base, and challenging prosthetic rehabilitation that was prone to failure. Early responses to Auxhausen’s challenge focused on primary bone grafting as developed by Schmid. As experience with the technique grew, reports emerged describing significant adverse effects on midfacial growth; although a few centers have continued to perform bone grafting in infants, most centers worldwide have abandoned the procedure.

Skoog introduced the concept of gingivoperiosteoplasty in the mid-1960s and demonstrated success at forming a bone bridge across the cleft towards the nasal side with soft tissue reconstruction only. Presurgical orthopedic devices, ranging from the pin-retained Latham appliance to soft tissue–borne nasoalveolar molding appliances, were developed in an effort to align cleft segments so that gingivoperiosteoplasty could be performed with less subperiosteal dissection and presumably fewer negative effects on growth. Unfortunately, even when successful in creating bone, these grafts provide insufficient support for erupting dentition in the majority of patients. Consequently, secondary grafting procedures are frequently required, and the specter of negative effects on growth remains.

In the 1970s Boyne and Sands introduced secondary bone grafting, or grafting during the mixed dentition. Their proposal was based on the concept that maxillary growth was 80% completed by 8 years of age; therefore, interventions after that time would lead to minimal growth disturbance but would still provide the benefits touted by advocates of primary grafting. Because the goals of maxillary construction are most comprehensively and predictably met with this technique, bone graft construction at a developmentally appropriate time during the mixed dentition remains the procedure of choice in most centers.

The best results were reported when grafts were placed during the mixed dentition and before cuspid eruption; the success rate is greater than 90% when this timing is used. Initially, survival of the canine was the primary dental focus after grafting. Now, however, optimal timing is based on evaluation of all salvageable permanent teeth adjacent to the cleft, including not only the canine, but also the lateral incisor. Grafting is ideally performed when two thirds of root development is complete for the tooth in question. This degree of root formation allows eruption of the tooth through the graft site in a timely manner, stimulating the graft and enhancing success. In addition, this should allow grafting to precede entry of the crown of the tooth into the cleft because any graft placed adjacent to an erupted crown will be lost, compromising the final result.

Despite the description of many bone sources for secondary bone grafting of the cleft maxilla, including calvarium, mandibular symphysis, rib, tibia, allogeneic bone, and bone morphogenetic protein–2 (BMP-2), cancellous bone from the ilium remains the gold standard.

Indications for the Use of the Procedure

Bone grafting of the cleft maxilla is an integral part of the habilitation of patients with cleft lip and palate. There are five specific goals to achieve when grafting the cleft maxilla. First, to provide bone support and adequate attached gingival width for teeth adjacent to the cleft. This is critical for long-term periodontal health and maintenance of the cleft-adjacent dentition. Secondly, to close the remaining oronasal fistula. The smaller more anterior defects associated with secondary grafting procedures do not generally cause significant speech disturbance but are an issue with regard to oral and upper respiratory tract hygiene. Thirdly, to improve support of the nasal alar base and lip on the affected side(s). This will allow for the appropriate bony foundation to enhance secondary cleft-related soft tissue revision procedures. Fourthly, to create an appropriate ridge form to allow for optimization of orthodontic care and dental alignment. Lastly, in the case of the bilateral cleft patient, to allow for stabilization of the premaxillary segment and to provide continuity of the maxilla as a whole.

Limitations and Contraindications

There are few true absolute contraindications for grafting the cleft maxilla outside of concerns related to the overall medical suitability for the patient to undergo general anesthesia and a surgical procedure safely. Relative contraindications include smoking, which impairs wound healing. Tobacco cessation before surgery is widely recommended and for many surgeons mandatory. In addition, significantly poor oral hygiene may lead to an increased postoperative infection rate.

The surgeon must also carefully consider traumatic occlusal forces leading to movement of the premaxilla during masticatory function, especially in the patient with a bilateral cleft maxilla. Movement of the premaxilla in the immediate postoperative period can substantially reduce the chance of bone graft success. These forces may be reduced by orthodontic treatment of the teeth out of traumatic occlusion, the application of a maxillary interocclusal splint, or surgical repositioning of the premaxilla out of traumatic occlusion via osteotomy.

Ideally, to minimize interventions in a population subject to a myriad of procedures, primary, supernumerary, or malformed teeth in the cleft region should be removed at the time of bone grafting. Additionally, periodontally involved teeth in the cleft site must be addressed at the time of operation. In rare circumstances, such as when non-salvageable teeth are located very superiorly and will impede watertight closure of the nasal mucosa, these teeth should be removed a few months before the procedure.

Once the maxillary canine on the affected side(s) have erupted fully, late grafting may still be performed, with the understanding that the success rate is lower and the goals are altered. The eruption process of the permanent dentition through the area of grafted bone is critical to the development of appropriate width of the graft and height of periodontal attachment of the affected dentition.

Technique: Bone Grafting of the Cleft Maxilla

Nasotracheal intubation is preferred on the non-clefted side if possible in unilateral cases; alternatively, an oral–Ring-Adair-Elwyn (RAE) tube secured in the midline may be used. Local anesthetic with 1 : 100,000 epinephrine is used to infiltrate the surgical field. Sterile preparation is performed. For the technical performance of the appropriate autogenous bone graft, see relevant chapters on mandibular, tibial, calvarial, costochondral, and iliac crest bone harvesting. It should be noted that the authors usually prefer the anterior iliac crest bone graft harvest for the early secondary reconstruction of the cleft maxilla in the mixed dentition.

Step 1:

Incision

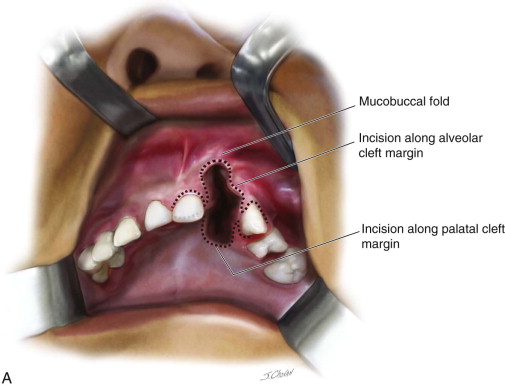

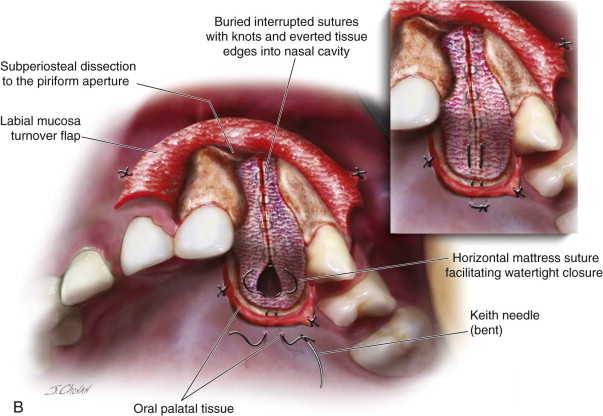

With a #15 blade, an incision is made along the cleft margin, separating the attached gingival tissues from the clefted region; carry this incision away from the cleft in a sulcular manner around the immediately adjacent teeth. This attached gingival tissue should be reflected and preserved. Continue the incision vertically along the cleft margin superiorly to the depth of the mucobuccal fold; the incision is carried through periosteum medially and laterally but must be shallower superiorly because it will be used to separate the oral and nasal layers, which have no intervening bone in this area. The incision should be continued palatally around the cleft margin; this is typically easiest to perform from the facial. The incisions around the cleft margin should be placed so that there is adequate tissue to facilitate closure of the nasal layer ( Figure 53-1, A, B ).

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses