Root damage is a significant complication of orthodontic miniscrew implant placement. Although root damage is rare, its proper management should be clearly understood by practitioners. This article reports the iatrogenic root perforation of a mandibular lateral incisor caused by the placement of a miniscrew. Despite a large radiolucent area caused by chronic apical periodontitis, the perforation was successfully repaired by using a recently developed material, mineral trioxide aggregate. The treatment, clinical implications, and clinical guidelines for preventing root damage during miniscrew placement in orthodontic practice are discussed.

Root damage is a significant complication of orthodontic miniscrew implants. Potential complications of root damage include ankylosis, osteosclerosis, and loss of tooth vitality.

Injury to the outer dental root without pulpal involvement might not influence the tooth’s prognosis. Asscherickx et al examined accidental damage to the roots during placement in beagle dogs. They reported that a defect was created in the root, but almost complete repair of the cementum occurred 12 weeks after removing the screws. Maino et al investigated the effects of contact between the drill or the miniscrew and the roots of 4 premolars in 2 adolescents with histologic analysis. They showed that contact between a dental root and a drill or screw caused resorptive root damage, but repair began through the deposition of cellular cementum after discontinuing contact. Kadioglu et al examined damage to root surfaces after intentional contact with miniscrews in 10 patients. They reported that swift repair and almost complete healing occurred within a few weeks after removing the screws. Although those articles present good prognoses, the injuries in their studies were limited to the outer root surfaces.

On the other hand, there are few reports of perforation damage caused by miniscrews. Generally, root injury involving the pulp tissue can result in loss of tooth vitality along with further destruction of the adjacent periodontal tissues. A root perforation can be treated through the access cavity or by surgical intervention. Surgical repair is indicated if the treatment of a perforation with an intracanal approach fails. This extracoronal approach is strongly recommended, particularly for root perforations by miniscrews, because most perforations occur on the lateral surface and are inaccessible through the access cavity.

Despite the increasing concern regarding the complications of miniscrew implants in orthodontic practice, there are few reports of root damage, particularly perforation, and its appropriate management. This report describes the surgical repair of a mandibular incisor with a lateral perforation caused by the placement of a miniscrew.

Case report

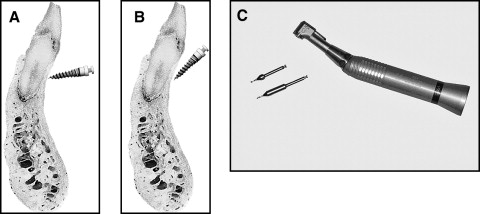

A 46-year-old man was referred to the Department of Conservative Dentistry of Chonnam National University, Gwangju, Korea. He was a patient in the orthodontic clinic, where his treatment included intrusion of the mandibular anterior teeth with miniscrews as anchorage. After 8 months of treatment, the practitioner found that he had perforated the root of a mandibular incisor and referred the patient to this institution for the management of this root damage ( Fig 1 , A ).

The patient had generalized periodontitis, particularly in the maxillary anterior area. The maxillary central incisors, which had been diagnosed as hopelesss, had been extracted. He had a severe deepbite and no room for maxillary restorations. The previous practitioner planned to intrude the mandibular anterior teeth to provide room for the maxillary restorations. He bonded a multistranded wire to the labial side of the mandibular incisors and placed 2 miniscrews in the interradicular area between the central and lateral incisors to intrude them with an elastic chain. However, a radiographic evaluation 8 months after the procedure showed that he had perforated the root of the right lateral incisor during screw placement. Also, the left-side screw had loosened 2 months before the referral.

A radiographic examination after removing the right-side screw showed a root perforation and a large radiolucent area surrounding the root apex, but the clinical examination showed no symptoms. Among the mandibular anterior teeth, only the right lateral incisor was not responsive to pulp sensitivity tests, including a cold test (Frigident, Ellman International, Hewlett, NY) and an electric pulp tester (Pulp Vitality Tester, Parkell, Edgewood, NY). The patient was diagnosed with chronic apical periodontitis caused by a lateral root perforation. Conventional endodontic treatment and surgical perforation repair was planned ( Fig 1 , B ).

After the initial consultation, the patient consented to have treatment, and endodontic therapy was initiated. An access cavity was prepared, and a rubber dam was placed. Pulp tissue extirpation was attempted. However, the original canal was not found during the trial of canal negotiation. It was believed that a perforated fragment had blocked the canal. Therefore, a surgical approach was considered necessary to remove the apical lesion and repair the perforation.

After local anesthesia with 2% lidocaine containing 1:80,000 epinephrine, a full thickness mucoperiosteal flap was elevated with a vertical incision from the distal aspect of the right mandibular first premolar to the distal aspect of the left mandibular central incisor. The surgical site was visualized by using a surgical microscope (OPMI pico, Carl Zeiss Surgical, Obekochen, Germany). Enucleated granulation tissue was observed in the lateral area of the right mandibular lateral incisor. The perforation site and the root apex were exposed through a bone window. The surgical field was debrided completely and irrigated, and the perforation site was cleaned. The perforation site was subsequently sealed with mineral trioxide aggregate (MTA) by using ProRoot (Dentsply/Tulsa Dental, Tulsa, Okla).

An apicoectomy was performed after sealing the perforation. The pathologic granulation tissue of the periapex was removed by using a surgical curette. Approximately 3 mm of the root apex was sectioned with a sterile fissure bur. The root-end cavity was prepared with an ultrasonic unit (Suprasson P-MAX, Satelec, Merignac, France) and filled with MTA. The flap was repositioned and sutured.

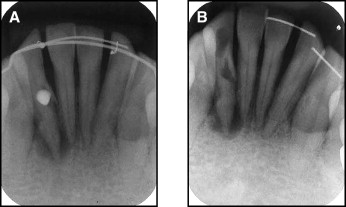

The sutures were removed 7 days after surgery. The patient was monitored at 3-month intervals. One year later, the radiograph showed significant bone healing. Clinically, the patient had no symptoms ( Fig 2 ).

Discussion

The complications of root damage depend on the degree of the injury. When screw-root contact is limited to the periodontal ligament space, the injury can be repaired with no further consequence. If the cementum is mechanically damaged and the dentin is exposed, multinucleated cells colonize the denuded surfaces, and resorption takes place. However, without further stimulation, the resorption process will stop spontaneously. Repair with cementum-like tissue will occur within 2 to 3 weeks. Recent clinical studies confirmed that repair occurs within a few weeks once the screw is removed. However, an irreversible response can occur when the affected area is large or the injury is deep. Ankylosis can occur if the affected area is large—ie, more than 4 mm 2 or 20% of the root surface. In addition, loss of tooth vitality can occur in patients whose injury is deep and involves the pulp tissue. Concomitant pulp necrosis results in destruction of the periapical and adjacent periodontal tissues. In this patient, the lateral portion of the root had been perforated by a screw, and the tooth lost vitality.

Root perforations adversely affect the prognosis of the tooth. The time between perforation and repair is a most critical factor for successful treatment. In this patient, the root was perforated during the placement of a miniscrew 8 months before the referral. It took a long time to realize that a root had been perforated. Some clinicians suggest that, when a screw touches a root, the practitioner can feel some resistance, and the patient feels discomfort or pain. However, this practitioner did not perceive the root damage during screw placement, even though the injury was deep. The periapical lesion was rather large, and the concomitant treatment procedure was considerably more complicated compared with conventional treatments.

The prognosis strongly depends on the treatment of bacterial infections at the perforation site. A poor prognosis is probably due to lack of biocompatibility and sealing capacity. For this reason, the selection of a suitable sealing material is essential for the successful management of a root perforation. MTA was reported to be an ideal material for retrograde filling and perforation repair. Main et al concluded that MTA provides effective sealing of a root perforation and can be considered a potential repair material that enhances the prognosis of perforated teeth.

MTA was developed as a root-end filling material in surgical endodontic treatments. It has been used for both surgical and nonsurgical applications, such as root-end filling, resorptive defect repair, direct pulp capping, apexification, and perforation repair. MTA has many advantages as a material for perforation repair, including good sealing characteristics, biocompatibility, bactericidal effects, radiopacity, and the ability to set in the presence of blood. Perforated roots treated with MTA showed a noninflammatory tissue layer and root cementum attached to the MTA. In our patient, MTA was used as a sealing material after removing the granulation tissue from around the perforation site. The follow-up radiographic and clinical evaluations indicated that MTA was a good sealing material.

MTA was also used as a retrograde filling material in this patient. Since pulp necrosis was evident in the involved tooth, conventional endodontic treatment was first attempted. However, it was not possible to reach the canal apex through the original canal possibly because of blockage by the perforated fragment. Therefore, perforation repair was performed without canal filling. Instead, a root-end resection was performed. MTA was used to fill the root-end cavity prepared with the ultrasonic unit.

Although this patient was managed successfully without further complications, root perforation is a potential cause of legal problems. Maximum effort should be made to avoid injury to the root during screw placement. Above all, particular attention should be paid to selecting the correct site for screw placement. If the site appears suspect in terms of root damage, a change of placement site should be considered, even though orthodontic mechanics might be rather unfavorable. For proper site selection, understanding the anatomic characteristics for candidate areas is necessary. Poggio et al provided an anatomic map, called the “safe zones,” to assist clinicians in miniscrew placement in safe locations between the roots. In our patient, the screws were placed between the central and lateral incisors. Because this area has a narrow safe zone, the placement site should have been changed to another area, such as between the lateral incisor and the canine, even though the orthodontic mechanics would have been less favorable.

The direction and the amount of subsequent orthodontic tooth movement should also be considered when selecting the screw placement point. In other words, the screw should allow for tooth movement of adjacent teeth. In this patient, intrusion of the mandibular incisors was planned to provide room for a maxillary restoration. Although the screws were placed some distance from the adjacent roots, contact can occur through intrusive movement of the adjacent teeth. The larger diameter portion of the root will approach the screw with an intrusion. Recent studies showed that root resorption occurred when a tooth moved against the screw during treatment. Some clinicians suggested using a surgical guide or wafer to prevent root damage in suspected situations. However, more attention should be paid when determining the safest site to avoid root damage.

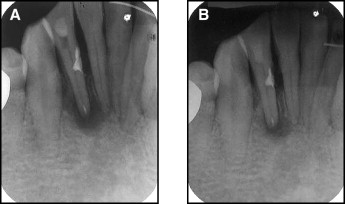

Although there are 2 placement methods—predrilling and no predrilling—a drill-free type of screw is preferred by many practitioners because of the simplicity of the procedure. A drill-free screw was used in this patient. On the other hand, slippage can occur when a screw is placed with vertical angulation. In other words, the screw is not engaged into cortical bone and slides under the soft tissue along the periosteum. A high-risk region for miniscrew slippage would be the mandibular anterior area because the bone is harder than in the maxilla and the slope is steeper than the posterior area in the mandible. The practitioner cannot provide vertical angulation in this area, and this increases the possibility of root damage. In this patient, the clinical examination showed that the screw had been placed without vertical angulation, probably to prevent possible screw slippage. Although the procedure for predrilling is rather complicated, its use might be advocated because making a pilot hole before screw placement can decrease the risk of screw slippage, particularly in the mandibular anterior area. Predrilling can be performed simply by using the recently developed pilot drill and speed-reduction hand piece even without making a flap ( Fig 3 ). We believed that the root damage in this patient could have been avoided if pilot drilling had been performed before the placing the screw.