A 13-year-old girl came with the chief complaint of an unesthetic dental appearance. Her maxillary canines were bilaterally impacted. Treatment included extraction of the maxillary canines and the mandibular second premolars. The maxillary first premolars were substituted for the canines. After 26 months of active treatment, the patient had a Class I molar relationship and ideal overbite and overjet. Her profile was improved, lips were competent, and gingival levels were acceptable. Cephalometric evaluation showed acceptable maxillary and mandibular incisor inclinations. Intraoral pictures taken 3 years 7 months after the end of treatment demonstrated that the extraction of impacted canines and their substitution by first premolars can be a valid alternative to traditional orthodontic treatment when maxillary premolar extraction is a treatment option.

The prevalence of impacted canines has been reported to be from 0.2% to 2.8%, and it is significantly higher in female subjects than in males (male:female ratio, 51:3).

In most patients, the impacted canines are ectopically positioned. Eighty-five percent are palatal to the dental arch. However, in a recent study of 156 ectopically positioned canines, 50% were in a palatal or distopalatal position, 39% in a buccal or distobuccal position, and 11% apical to the adjacent incisor or between the roots of the central and lateral incisors. Various etiologic factors have been implicated for impacted maxillary canines: eg, ectopic position of the tooth germ, lack of space, lack of guidance, and genetic factors.

Maxillary canines play an important role in creating good facial and smile esthetics, since they are positioned at the corners of the dental arch, forming the canine eminence for support of the alar base and the upper lip. Furthermore, when the maxillary canines are properly aligned and have good shape and size, pleasing anterior dental proportions and correct smile lines are achieved. Functionally, they support the dentition, contributing to disarticulation during lateral movements in certain persons.

Impacted canines can be successfully aligned in the arches by a combined orthodontic-surgical approach, and several treatment strategies have been proposed. Such complex therapeutic management should be considered successful if the impacted canine is properly aligned in the dental arch with a healthy periodontium. However, some adverse effects related to the orthodontic extrusion of an impacted canine have been described in the literature. Differences in tooth color, alignment, vitality, probing pocket depth, and crestal bone and gingival margin heights have been reported between the previously impacted canine and its contralateral tooth. Furthermore, apical root resorption and loss of hard and soft periodontal tissues have been observed in teeth adjacent to the extruded canine.

Although the treatment of choice for an impacted canine is a combined surgical-orthodontic approach, an alternative treatment in a patient with bilateral palatally impacted canines is presented.

Diagnosis and etiology

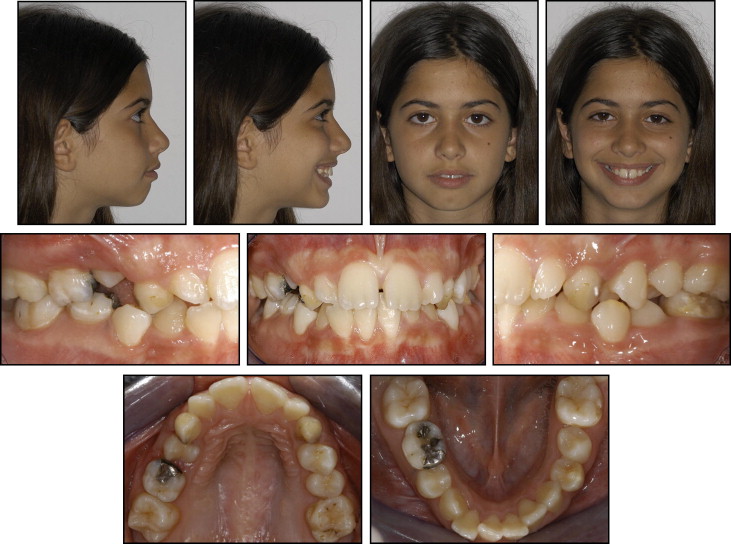

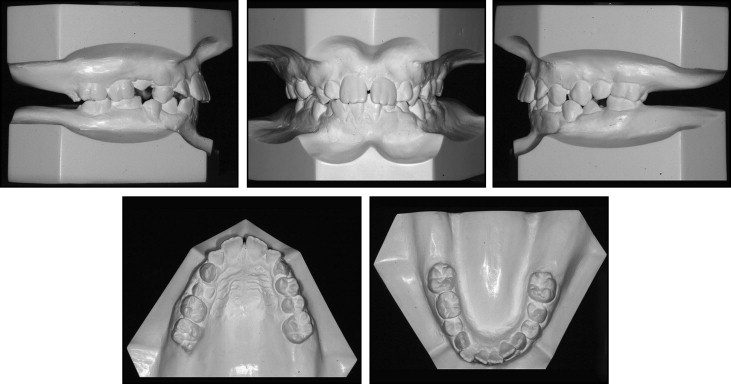

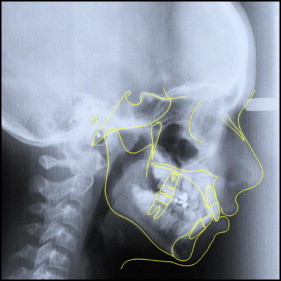

A 13-year-old girl came with the chief complaint of an unesthetic dental appearance ( Figs 1-4 ). The facial analysis showed a mandibular retrognathic profile, incompetent lips, perioral muscular strain, and a slightly protrusive dentition upon smiling. The intraoral examination showed a healthy periodontium, mild maxillary transverse constriction, and moderate crowding in the maxillary and mandibular arches. A Class I molar relationship was present, and all teeth were erupted except for the maxillary canines, maxillary and mandibular right second premolars, and maxillary second molars. The panoramic radiograph showed bilateral maxillary canine impaction. The right canine was high with respect to the occlusal plane and horizontally oriented. Lack of spaces for second and third molar eruption in the mandibular arch was also noticeable. The cephalometric analysis showed an acceptable vertical and anteroposterior skeletal relationship, with moderate proclination of the maxillary and mandibular incisors ( Table ). A familial history of maxillary impacted canines suggested that the etiology of this malocclusion could be partially genetic.

| Measurement | Pretreatment | Posttreatment |

|---|---|---|

| Horizontal skeletal | ||

| SNA (°) | 88.4 | 84.3 |

| SNB (°) | 85.4 | 78.3 |

| ANB (°) | 3.0 | 6.0 |

| Maxillary skeletal (A-Na perp) (mm) | 2.7 | 7.6 |

| Mandibular skeletal (Pg-Na perp) (mm) | −0.3 | 4.2 |

| Wits (mm) | −5.1 | 1.6 |

| Vertical skeletal | ||

| FMA (MP-FH) (°) | 22.8 | 17.3 |

| MP-SN (°) | 27.5 | 30.5 |

| Palatal-mandibular angle (°) | 25.1 | 20.5 |

| Palatal-occlusal plane (°) | 12.9 | 9.0 |

| Mandibular plane to occlusal plane (°) | 12.1 | 11.6 |

| Anterior dental | ||

| Maxillary incisor protrusion (mm) | 9.7 | 1.6 |

| Mandibular incisor protrusion (mm) | 5.9 | −2.2 |

| U1-PP (°) | 114.9 | 107.1 |

| U1-occlusal plane (°) | 52.1 | 64.0 |

| L1-occlusal plane (°) | 71.1 | 80.5 |

| IMPA (°) | 96.7 | 87.9 |

Treatment alternatives

Nonextraction and extraction plans were considered.

The maxillary and mandibular dental arches could have been aligned and leveled without the extraction of any permanent teeth by means of interproximal enamel reduction and dentoalveolar expansion. After the creation of adequate space, the maxillary canines could have been erupted by a combined orthodontic-surgical approach. However, because of the crowding, the dentoalveolar biprotrusion, and the incompetent lips, this treatment plan could have led to a more severe dentoalveolar biprotrusion and would not have addressed lip incompetence. In addition, excessive incisor proclination could have had a questionable effect on long-term stability.

Crowding associated with dentoalveolar biprotrusion is efficiently corrected by maxillary and mandibular first premolar extractions. In this patient, premolar extractions would have also addressed lip incompetence and created space for easier extrusion of the impacted canines. The anchorage could be provided by a palatal miniscrew because the bone shape was suitable. However, a long treatment time could have been required, and the risks related to orthodontic extrusion of impacted canines could not have been ruled out. In addition, because of the highly unfavorable maxillary left canine position, successful extrusion of this tooth would not have been ensured.

An alternative orthodontic treatment plan required maxillary and mandibular second premolar extractions. It would have allowed aligning and leveling of the arches, reduction of the dentoalveolar biprotrusion, and an improved facial appearance. In addition, mandibular second premolar extractions (compared with first premolar extractions) might have reduced the amount of incisor retraction during space closure, resulted in less flattening of the profile, and provided more space for easier molar eruption.

The treatment plan selected included surgical extraction of the maxillary impacted canines and the mandibular second premolars; the maxillary first premolars would replace the canines. This option allowed us to reduce treatment time, improve the facial profile and lip competence, and achieve alignment and leveling of the arches without incisor proclination.

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses