This article provides a review of the traditional clinical concepts for the design and fabrication of removable partial dentures (RPDs). Although classic theories and rules for RPD designs have been presented and should be followed, excellent clinical care for partially edentulous patients may also be achieved with computer-aided design/computer-aided manufacturing technology and unique blended designs. These nontraditional RPD designs and fabrication methods provide for improved fit, function, and esthetics by using computer-aided design software, composite resin for contours and morphology of abutment teeth, metal support structures for long edentulous spans and collapsed occlusal vertical dimensions, and flexible, nylon thermoplastic material for metal-supported clasp assemblies.

Key points

- •

Although classic theories and rules for removable partial dentures (RPDs) designs have been presented and should be followed, excellent clinical care for partially edentulous patients may also be achieved with computer-aided design (CAD)/computer-aided manufacturing (CAM) technology and unique blended designs.

- •

These nontraditional RPD designs and fabrication methods provide for improved fit, function, and esthetics using CAD software, composite resin for contours and morphology of abutment teeth, metal support structures for long edentulous spans and collapsed occlusal vertical dimensions, and flexible nylon thermoplastic material for metal-supported clasp assemblies.

Rationale and indications for RPDs

The primary reason often cited for the fabrication and delivery of an RPD for dental patients is the replacement of missing teeth in a cost-effective manner. Most clinicians also choose an RPD for a partially edentulous patient if they need to restore lost residual ridge, achieve appropriate esthetics, increase masticatory efficiency, and improve phonetics but are unable to do so with dental implants or fixed partial dentures due to financial constraints or patient desires ( Figs. 1–4 ).

In certain situations, RPDs are indicated as a choice of treatment of partially edentulous patients when the length of the edentulous span contraindicates a fixed partial denture, there is a need for residual ridge support for mastication, or a patient has a guarded prognosis for their periodontal condition ( Figs. 5–8 ). Other indications for RPDs are excessive loss of residual ridge, a requirement for a denture base flange, obtaining proper tooth position not achievable due to the biomechanics of dental implants, patient dexterity and oral hygiene issues, and a large maxillofacial defect requiring cross-arch stabilization.

Rationale and indications for RPDs

The primary reason often cited for the fabrication and delivery of an RPD for dental patients is the replacement of missing teeth in a cost-effective manner. Most clinicians also choose an RPD for a partially edentulous patient if they need to restore lost residual ridge, achieve appropriate esthetics, increase masticatory efficiency, and improve phonetics but are unable to do so with dental implants or fixed partial dentures due to financial constraints or patient desires ( Figs. 1–4 ).

In certain situations, RPDs are indicated as a choice of treatment of partially edentulous patients when the length of the edentulous span contraindicates a fixed partial denture, there is a need for residual ridge support for mastication, or a patient has a guarded prognosis for their periodontal condition ( Figs. 5–8 ). Other indications for RPDs are excessive loss of residual ridge, a requirement for a denture base flange, obtaining proper tooth position not achievable due to the biomechanics of dental implants, patient dexterity and oral hygiene issues, and a large maxillofacial defect requiring cross-arch stabilization.

Communicating RPD designs to the laboratory

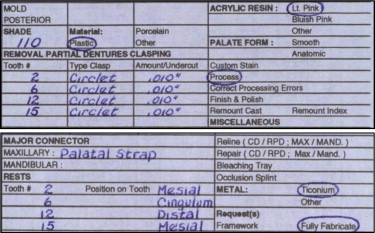

In the United States, individual state dental boards mandate that dentists complete a laboratory work authorization form for the fabrication of an RPD by a dental laboratory. This work authorization form is actually a prescription to a dental laboratory for this service and should be completed accurately with as much attention to detail as possible. In most states, because it is considered a legal document, dentists must also keep a copy of the signed authorization form on file for several years.

As with prescriptions for medications, there are certain items that should be included on a laboratory work authorization in addition to a dentist’s signature and license number, date, and patient name and address. Most important is a description of the kind and type of laboratory service desired as well as details of the design and the materials to be used for the RPD ( Fig. 9 ).

Dentists should accurately describe the following features and components of an RPD on the laboratory work authorization form:

- 1.

Major connector

- 2.

Type of metal and acrylic resin

- a.

Framework only

- b.

Fully fabricate

- i.

Shade, mold, and type of material for artificial teeth must be included

- ii.

Denture base color and characterization

- i.

- a.

- 3.

Tooth numbers

- a.

Type of clasps

- b.

Amount and location of retentive undercuts

- c.

Type and location of metal rests

- a.

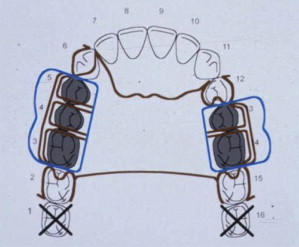

In order to enhance communication with the dental laboratory, the definitive RPD design can be drawn in color on the laboratory work authorization form ( Fig. 10 ). A key for success is to make sure that the color-coded design drawn on the work authorization is the same as the description written on the form. If not, then sometimes the best advice for dentists is to listen to the laboratory technician for feedback on what changes are necessary in order to fabricate an RPD in the laboratory to restore form, function, and esthetics as prescribed by the clinician. As an example, note how the design drawn in Fig. 10 shows replacement of teeth 3, 4, 5, 13, and 14 with a Kennedy class III maxillary RPD design, but space limitations allowed the laboratory to place only 3 denture teeth, instead of the 5 requested by the clinician ( Fig. 11 ).

Review of RPD theories and classic designs

In 1925, Dr Edward Kennedy proposed 4 distinct categories to classify maxillary and mandibular partially edentulous arches—classes I, II, III, and IV—in an attempt to suggest principles of design for a particular situation. Each of the 4 Kennedy classifications refers to a single edentulous area, except class I, which refers to bilateral posteriorly extended edentulous areas. In 1954, Dr Oliver C. Applegate proposed additional edentulous areas within each arch, referred to as “modification spaces,” for applying the Kennedy classification method ( Fig. 12 ).

In his textbook, Applegate described 8 rules for classification of modification spaces. His most important rule to remember is, “the most posterior edentulous area(s) being restored always determine(s) the classification.” Modification spaces under rule 8 are not allowed for a Kennedy class IV partially edentulous arch, because it is an anterior partially edentulous space bounded posteriorly by natural dentition ( Figs. 13 and 14 ).

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses