4

Red and White Lesions of the Oral Mucosa

Ivan Alajbeg, DMD, MSc, PhD,

Stephen J. Challacombe, PhD, FDS RCSEd, FRCPath, FMedSci

Palle Holmstrup, DDS, PhD,

Mats Jontell, DDS, PhD, FDS RCSEd

RED AND WHITE TISSUE REACTIONS

One challenging aspect of oral medicine is that many lesions of different conditions look alike. The same diagnosis may also manifest in various ways. Thus, in order to become a successful clinician in differential diagnosis, appreciation of the very versatile appearances of the same disease requires considerable clinical acumen and experience. It is also important to appreciate that the oral mucosa in some patients may appear to be different from what we perceive as normal‐looking mucosa.

There are different ways of classifying oral mucosal lesions. One is in accordance with the most prominent colors in which they can manifest. The difference that we (or our patient) see often is the change of color. Observing those changes is important as they guide us in establishing the diagnosis.1 Although many shades of different colors may appear in the mouth indicating pathologic changes, two of the most striking ones are red and white. Following this rather rough and nonspecific truncation, we need to refine the features to obtain the correct diagnosis.

“White lesion” stands for any mucosal area that appears whiter than its adjacent tissue. It does not represent a specific etiologic or microstructural group of mucosal conditions. Its surface is usually also of a different texture, or may be raised from its surroundings. When considering red and white lesions, we are assuming that the epithelial integrity is still preserved, as otherwise we would have ulceration. Indeed, within the time course of a single oral condition, we can see different stages and intensities. Its current red and/or white appearance can progress toward an ulcerative stage (e.g., in lichen planus), which may appear whitish or yellowish due to fibrinous exudate and pseudomembranes. Therefore, there is a temporal component to the clinical appearance of the condition with a tendency to change over time. Thus, classifying those oral conditions exclusively according to their red or white appearance cannot be fully feasible. All red and white lesions may present in combinations of all of the above.

White lesions of oral mucosa are white as a consequence of several possible structural occurrences:2

Figure 4‐1 Mechanisms leading to a white appearance of the oral mucosa due to an increased production of keratin (hyperkeratosis).

Figure 4‐2 Mechanisms leading to a white appearance of the oral mucosa due to an abnormal but benign thickening of stratum spinosum (acanthosis).

- Increased thickness of the corneal layer (in keratinized epithelium).

- Keratinization of epithelium that does not normally contain a corneal layer (nonkeratinized epithelium). Both (1) and (2) manifest as hyperkeratosis (Figures 4‐1 and 4‐2).

- Formation of abnormal keratin.

- Epithelial edema: intra‐ and extracellular accumulation of fluid in the epithelium may also result in clinical whitening (Figure 4‐3).

- Abnormal keratinization occurring prematurely within individual cells or groups below the stratum granulosum (dyskeratosis often also contains hyperkeratosis).

Figure 4‐3 Mechanisms leading to a transparent white appearance of the oral mucosa due to intra‐ and extracellular accumulation of fluid in the epithelium (leukodema).

- Subepithelial superficial fibrosis, which with its decreased vascularity network causes a diffuse whitish appearance; Any overall epithelial thickening (acanthosis) itself does not seem to cause whiteness.

Keratins are a family of fibrous scleroproteins, which form intermediate filaments necessary for maintaining the structural integrity of keratinocytes and thus for epithelial protection and support. Keratin present in the white oral lesion is likely to be different from keratin normally occurring in oral mucosa (e.g., that produced on the hard palate or attached gingiva). This type of keratin resembles the keratin on the skin, and absorbs water when overly hydrated by oral fluids, resulting in swelling and a white appearance similar to that of skin immersed in water for a prolonged time. Any of those also changes the refractive index as well as causes different reflection and dispersion of light waves, which we see as white.

Apart from structural epithelial changes, a white or “whitish” appearance may result from exogenous deposits, such as microbial colonies (e.g., candidal mycelium) and their effects on the host surface (exudate, necrotic cellular debris, and metabolic products). Fungi can, thus, produce whitish pseudomembranes consisting of sloughed epithelial cells, fungal mycelium, and neutrophils, which are loosely attached to the oral mucosa (Figure 4‐4).

Clinicians should be aware of the possibility of being misled by the color of fibrin pseudomembranes. There are many shades of grayish and whitish fibrin pseudomembranes that to the unskilled eye can resemble the white appearance of hyperkeratosis, whereas it is fibrin covering an ulcerated area. Sometimes a fibrin pseudomembrane can present a yellowish appearance and one should not mistake it for purulent matter or infection.

The pink appearance of oral mucosa results from tissue translucency, allowing the light to pass through the epithelium into the lamina propria and reflect the blood vessels containing hemoglobin.

A red lesion of the oral mucosa may develop as the result of atrophic epithelium (Figure 4‐5), characterized by a reduction in the number of epithelial cells. It may also be the result of loss of the superficial cell layers (superficial erosion, Figure 4‐6) or increased vascularization due to proliferation of vessels. Redness or erythema may further be caused by dilatation of vessels associated with inflammation of the oral mucosa, reduced epithelial keratinization, and, importantly, cellular proliferation signifying a possible malignancy.

Oral mucosal lesions also present with different tissue surface consistency, and white lesions may appear as reticular, plaque‐like, papular, or pseudomembranous, which affect the clinical appearance of the lesions. Most red, and particularly most white, lesions are benign. Red lesions may also display a change of surface texture, which may become granular, velvety, and rough. It is important to note those features, as they are suggestive of neoplasia. Palpation of white and red lesions is necessary in addition to inspection, as indurated lesions should draw additional suspicion for possible malignancy.3

Our clinical approach to differential diagnosis should appreciate many other features of the lesion (Table 4‐1). These include presence of pain, single versus multiple lesions, distribution in specific areas, the borders toward the unaffected tissue (clear or hazy, straight or crooked), onset, duration, change in shape and size, whether it is raised in comparison to surrounding mucosa, its relapsing nature, and reasons for improvement or exacerbation.

In addition to more detailed assessment of oral condition, we also need to obtain a closer and better understanding of the whole patient. A patient’s specific systemic condition and associated medications are potentially very closely related to oral disease, so knowing and understanding them may be very relevant to the oral condition. However, there are cases in which patients are unaware of their systemic conditions. Thus, by recognizing oral lesions, we sometimes note the initial indication of possibly undiagnosed systemic disease. Age can also be a significant factor in differentiating between similarly presenting conditions, which is perhaps more important for some other instances than most of those described in this chapter, such as the relevance of enlarged neck lymph nodes in children (frequent reactive lymphadenitis) and adults aged 65 years or older (more likely to represent malignancy), as well as in cases of mouth ulcers in young and old patients (discussed elsewhere).

Figure 4‐4 Mechanisms of a white appearance of the oral mucosa due to microbes, particularly fungi, which can produce whitish pseudomembranes consisting of sloughed epithelial cells, fungal mycelium, and neutrophils, which are loosely attached to the oral mucosa (plaques).

Figure 4‐5 Mechanisms leading to a red appearance of the oral mucosa; a red lesion of the oral mucosa may develop as the result of an atrophic epithelium (atrophy).

Figure 4‐6 Mechanisms leading to a red appearance of the oral mucosa characterized by a reduction in the number of epithelial cells or increased vascularization; that is, dilatation of vessels and/or proliferation of vessels.

Table 4‐1 Main clinical characteristics of red or white lesions.

| Is pain present? |

| Are lesions single or multiple? |

| Are lesions bilateral or unilateral? |

| Is the distribution of lesions linked to mucosal type? |

| Are lesion borders defined or indistinct? |

| Date of onset |

| Are lesions associated with changes of the skin? |

| Duration of lesion |

| Any changes in shape, size, or texture with time? |

| Any previous response to therapy? |

| What makes the pain or the lesions worse? |

| Have lesions healed and recurred? |

INFECTIOUS DISEASES

Oral Candidiasis

Oral candidiasis is the most prevalent opportunistic infection affecting the oral mucosa. It is common, but often wrongly considered by the unskilled as a culprit for many oral conditions or white lesions. In the vast majority of cases, oral candidiasis is caused by Candida albicans. C. albicans is one of the components of normal oral microflora and more than 60% of people carry this organism. Rate of carriage increases with age of the patient and C. albicans can be found in over 60% of dentate patients over the age of 60 years. Most candidal infections only affect mucosal linings, and vaginal candidiasis is said to affect 50% of the female population of the planet at one time or another. There are many different additional Candida species that can be seen in the oral cavity, including C. glabrata, C. guillermondii, C. krusei, C. tropicalis, C. parapsilosis, C. pseudotropicalis, and C. stellatoidea. Candidiasis is often referred to as a disease of the diseased and is associated with underlying hematologic or immunologic deficiencies and a huge increase in the numbers of oral candida, as well as the conversion from the commensal yeast form (saprophytic stage) to the infecting pathogenic (parasitic) form. Thus it is incumbent on clinicians to determine the reasons for oral candidiasis, not just prescribe antifungals.

Candidiasis is said to affect in particular the very young, the very old, the very dry, and the very sick. Every candidiasis starts after local or systemic factors enable commensal Candida to become pathogenic. Those local factors include lack of saliva (medications causing dry mouth, autoimmune diseases, head and neck radiotherapy), denture wearing, topical steroid use, use of antibiotics or immunosuppressive drugs, systemic conditions including diabetes, anemia, or HIV, as described in detail in this chapter. Rare systemic manifestations of candidal infections may have a fatal course and are major causes of morbidity and mortality, causing a variety of diseases from mucosal infections to deep tissue disease, which may lead toward candidemia and organ involvement. Systemic candidal infections are mostly limited to hospital patients who are immunocompromised or with other severe comorbidities.4

Oral medicine largely deals with oral mucosal candidal infections, but also considers local or systemic disturbances that may predispose to fungi becoming invasive instead of remaining commensal. Candidal infections encountered in an oral medicine setting usually do not result in serious consequences for overall health, but can produce discomfort (inflammation may cause tenderness) or may change a person’s appearance (e.g., angular cheilitis). Successful treatment depends on identifying and eliminating predisposing factors. On rare occasions, a longstanding intractable candidal infection in individuals with disturbed immune responses may produce granulomatous reactions.

Classification

There have been a number of classifications, but the most useful is that which combines chronicity with clinical presentation, as seen in Table 4‐2. Pseudomembranous lesions present with removable small white plaques (see later), while erythematous lesions present essentially as red lesions with no white plaques.5 These are both superficial forms of candidiasis, whereas all chronic hyperplastic forms are associated with hyphae driving down within the epithelium (Table 4‐2). Oral forms may also be associated with candidiasis affecting extraoral sites, usually in conditions or genetic diseases where normal innate or adaptive host responses are compromised (Table 4‐3).

Etiology and Pathogenesis

C. albicans, C. tropicalis, and C. glabrata comprise together over 80% of the species isolated from human mucosal candidal infections. To invade the mucosal lining, the microorganisms must adhere to the epithelial surface, therefore candidal strains with better adhesion potential are more virulent than strains with poorer adhesion ability.6 Penetration of the epithelial cells by yeasts is facilitated by their production of lipases and proteinases, and for the yeasts to remain within the epithelium, they must overcome constant desquamation of surface epithelial cells.7

There is an association between oral candidiasis and the influence of local and general predisposing factors. The local predisposing factors (Table 4‐4) are able to promote growth of the yeast or to affect the immune response of the oral mucosa. General predisposing factors are often related to an individual’s immune and endocrine status (Table 4‐4). Drugs as well as diseases that suppress the adaptive and innate immune systems can affect the susceptibility of the mucosal lining. Pseudomembranous candidiasis is also associated with fungal infections in young children, who have neither a fully developed immune system nor a fully developed oral microflora.

Table 4‐2 Classification of oral candidiasis.

| Type | Examples |

|---|---|

| Pseudomembranous—acute Pseudomembranous—chronic |

Thrush With inhalers |

| Erythematous—acute atrophic Erythematous—chronic atrophic |

After antibiotic therapy Denture stomatitis; in HIV |

| Chronic hyperplastic (nodular and plaque‐like subtypes) | Candidal leukoplakia, median rhomboid glossitis |

| Candida‐associated lesions | Denture stomatitis; angular cheilitis |

Table 4‐3 Candidiasis affecting extraoral sites and conditions predisposing to candidiasis.

| Familial chronic mucocutaneous candidiasis Diffuse chronic mucocutaneous candidiasis Erythematous candidiasis endocrinopathy syndrome Chronic severe combined immunodeficiency DiGeorge syndrome Chronic granulomatous disease HIV disease |

Table 4‐4 Predisposing factors for oral candidiasis.

| Local Predisposing Factors for Oral Candidiasis and Candida‐Associated Lesions | General Predisposing Factors for Oral Candidiasis |

|---|---|

| Denture wearing Smoking Inhalation steroids Topical steroids Hyperkeratosis Quality and quantity of saliva Atopic constitution Imbalance of the oral microflora |

Immunosuppressive diseases Immunosuppressive drugs Chemotherapy Endocrine disorders, e.g., diabetes Hematinic deficiencies Systemic antibiotics Impaired health status |

Denture stomatitis and angular cheilitis are referred to as Candida‐associated infections, as they are always associated with raised counts of intraoral Candida and also since bacteria may cause these infections.

Epidemiology

The prevalence of candidal strains as part of the commensal oral flora shows large geographic variations, often also related to the method of culture, but an average figure of 50% is generally accepted. Candidal strains are more frequently isolated from women and the vaginal carriage is similar. Hospitalized patients have a higher prevalence, presumably related to comorbidities. In complete denture wearers, the prevalence of Candida associated with denture stomatitis has been reported as nearly 70%. There is a view that candidiasis is frequently over‐reported in those without experience of the normal anatomy of the oral cavity. Thus, even slight elongation of the filiform papillae on the dorsum of the tongue may be erroneously diagnosed as candidiasis, as may be almost any white patch in the oral cavity. This misconception is found not only among lay people, but also among many medical and dental professionals.

Clinical Findings

Pseudomembranous Candidiasis

The acute form of pseudomembranous candidiasis (thrush; see Table 4‐2) is recognized as the classic candidal infection (Figure 4‐7). The infection predominantly affects patients taking antibiotics, immunosuppressant drugs, or having a disease that suppresses the immune system.

The infection typically presents with loosely attached membranes comprising fungal organisms and cellular debris (desquamated epithelial cells and polymorphonuclear lymphocytes), which leaves an inflamed, sometimes bleeding area if the pseudomembrane is removed. Less pronounced infections sometimes have clinical features that are difficult to discriminate from food debris like egg and yoghurt. There is also a chronic form of pseudomembranous candidiasis, often associated with immunodeficiency. The clinical presentations of acute and chronic pseudomembranous candidiasis are indistinguishable. The chronic form may emerge as the result of HIV infection, as patients with this disease may be affected by a pseudomembranous candidal infection for a long period of time. Patients treated with steroid inhalers may also show pseudomembranous lesions of a chronic nature. Patients infrequently report symptoms from their lesions, although some discomfort may be experienced from the presence of the pseudomembranes.

Figure 4‐7 Pseudomembranous candidiasis at the soft palate, uvula, and palatoglossal arches during the immunosuppressive phase following heart transplantation.

Figure 4‐8 Erythematous candidiasis caused by inhalation steroids (A) on the dorsum of the tongue and (B) the associated contact (kissing) lesion on the hard palate.

Erythematous Candidiasis

The erythematous form of candidiasis was previously referred to as atrophic oral candidiasis. However, an erythematous surface may not just reflect atrophy but can also be explained by increased vascularization. In addition, the erythematous form seen on the tongue in HIV infection is associated with loss of lingual papillae and a contact lesion on the hard palate. Lesions of erythematous candidiasis have a diffuse border (Figure 4‐8), which helps distinguish them from erythroplakia, which usually has a sharper demarcation and often appears as a slightly submerged lesion. Quantitative analysis of Candida counts in saliva will reveal raised counts in all forms of candidiasis. The infection is also seen in the palate and the dorsum of the tongue of patients who are using inhalation steroids. Other predisposing factors that can cause erythematous candidiasis are smoking and treatment with broad‐spectrum antibiotics. The acute and chronic forms present with identical clinical features.

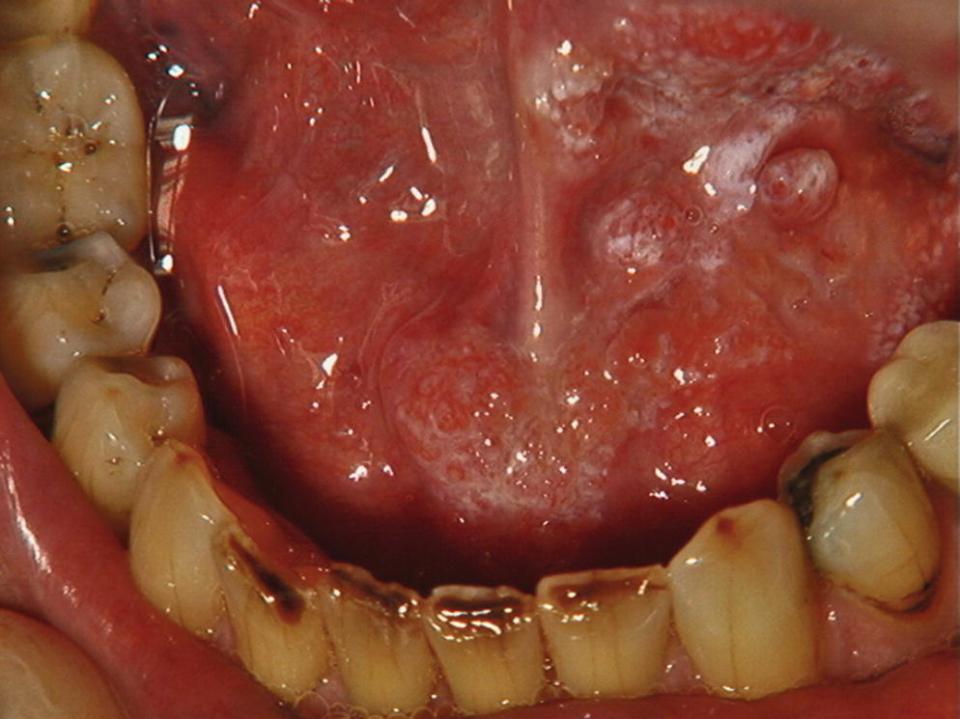

Chronic Hyperplastic Candidiasis (Chronic Plaque Type and Nodular Candidiasis)

The chronic plaque type of oral candidiasis is synonymous with the older term candidal leukoplakia. A white irremovable plaque characterizes the typical clinical presentation, which may be indistinguishable from oral leukoplakia (Figure 4‐9). A histologic feature (see later) is the penetration of candidal hyphae through the epithelial cells and the associated subepithelial chronic inflammatory response (Figure 4‐10). This often results in mild to moderate dysplasia, especially in the chronic plaque type and the nodular type of oral hyperplastic candidiasis (Figure 4‐11). This is considered reversible with treatment, but very rarely cases go on to malignant transformation. It has been hypothesized that Candida species may induce this transformation through their capacity to catalyze nitrosamine production, which is carcinogenic.8

Median Rhomboid Glossitis

Median rhomboid glossitis is clinically characterized by an erythematous lesion in the center of the posterior part of the dorsum of the tongue (Figure 4‐12). As the name indicates, the lesion has an oval configuration. This area of erythema results from atrophy of the filiform papillae and the surface may be lobulated. The etiology is not fully clarified, but biopsies yield candidal hyphae in more than 85% of the lesions.9 Smokers and denture wearers have an increased risk of developing median rhomboid glossitis, as well as patients using inhalation steroids. Sometimes a concurrent erythematous lesion may be observed in the palatal mucosa (contact lesion). Median rhomboid glossitis is asymptomatic, and management is restricted to a reduction of predisposing factors and systemic antifungals.

Although it may cause concern for patients who either discover the lesion themselves (e.g., while self‐examining in search for symptoms, such as in burning mouth syndrome) or via health professionals, the lesion does not entail any increased risk for malignant transformation. Unlike the lateral and ventral tongue, cancer is very rare on the dorsal tongue and virtually nonexistent right in its center. If a biopsy of median rhomboid glossitis is taken, one should be aware that it can easily be misinterpreted by pathologists as being malignant.10 Although it is a benign lesion, histologically it simulates cancer, which is why it has been styled “pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia” (epithelioma is a historical term for cancer). Elongated rete pegs resemble nests of cancer cells. Histopathology findings of deeper layers show muscular fibrosis and hyalinization (which are increased by excision). Therefore, neither biopsy nor surgical intervention is recommended in cases of median rhomboid glossitis.

Figure 4‐9 (A) Chronic hyperplastic candidiasis inside the right commissure. This white plaque is not removable, was bilateral, and histology (Figure 4‐10) showed hyphae penetrating through epithelial cells. (B) Plaque type chronic candidiasis in the right buccal mucosa.

Figure 4‐10 Periodic acid–Schiff (PAS) staining of a biopsy from chronic hyperplastic candidiasis (Figure 4‐9A) showing invading hyphae drilling through oral epithelial cells.

Figure 4‐11 Chronic nodular candidiasis in the left retro‐commissural area.

Figure 4‐12 Median rhomboid glossitis apparently arising from the junction of the posterior third and anterior two‐thirds of the tongue. Histology confirmed chronic hyperplastic candidiasis.

Denture Stomatitis

The most prevalent site for denture stomatitis is the denture‐bearing palatal mucosa (Figure 4‐13), whether acrylic or chrome cobalt. It is unusual for the mandibular mucosa to be involved. Candida resides on the denture surface, and the erythema appears to be a mucosal reaction to Candida and other microorganisms.

Figure 4‐13 Chronic atrophic candidiasis (denture stomatitis) type III with a granular mucosa in the central part of the palate.

Denture stomatitis is classified into three different types:

- Type I is limited to erythematous sites caused by trauma from the denture.

- Type II affects a major part of the denture‐covered mucosa.

- Type III has a granular mucosa (reactive proliferation of underlying fibrous tissue) in addition to the features of type II. The denture serves as a vehicle that accumulates sloughed epithelial cells and protects the microorganisms from physical influences such as salivary flow.

The microflora is complex and may, in addition to C. albicans, contain bacteria from several genera, such as Streptococcus, Veillonella, Lactobacillus, Prevotella (formerly Bacteroides), and Actinomyces strains. It is not known to what extent these bacteria participate in the pathogenesis of denture stomatitis. Nearly every patient with denture stomatitis will report wearing dentures overnight. Thus, denture stomatitis is the consequence of continuous irritation, both microbial and mechanical from the upper denture, on the underlying mucosal surface. The term “denture sore mouth” is a misnomer, as it normally does not produce any symptoms and is usually diagnosed by the dentist, since patients are frequently unaware. Oral medicine specialists still get referrals with a misdiagnosis of allergy to the denture.

Angular Cheilitis

Angular cheilitis presents as infected fissures of the commissures of the mouth, often surrounded by erythema (Figure 4‐14). The lesions are frequently co‐infected with both Candida albicans and Staphylococcus aureus. Atopy, vitamin B12 deficiency, iron deficiencies, and loss of vertical dimension are all associated with this disorder. The reservoir for Candida in the cheilitis is intraoral, so treatment must not be limited to the commissures. Many patients with angular cheilitis will also have denture stomatitis.

Oral Candidiasis Associated with HIV

More than 90% of AIDS patients have had oral candidiasis during the course of their HIV infection, and the infection is considered a portent of AIDS development (Figure 4‐15). Oropharyngeal candidiasis is related to the degree of immunosuppression and is most often observed in patients with CD4 counts <200 cells/mL. The most common types of oral candidiasis in conjunction with HIV are chronic pseudomembranous candidiasis, erythematous candidiasis of the middle of the tongue and palate, and angular cheilitis. As a result of antiretroviral therapy (ART), the prevalence of oral candidiasis has decreased substantially. Oral candidiasis associated with HIV infection is presented in more detail in Chapter 21, “Infectious Diseases.”

Figure 4‐14 Candida‐induced bilateral angular cheilitis. Treatment must include the intraoral Candida reservoir.

Figure 4‐15 Erythematous candidiasis of the central part of the tongue in an AIDS patient. Hairy leukoplakia can be seen at the right lateral border.

Clinical Manifestations of Mucocutaneous Candidiasis

More widespread candidiasis (see Table 4‐3), besides oral involvement, is accompanied by systemic mucocutaneous candidiasis and other immune deficiencies. Chronic mucocutaneous candidiasis (CMC) embraces a heterogeneous group of disorders, but is characterized by recurrent or persistent infections affecting the nails, skin, and oral and genital mucosae caused by Candida species (Figure 4‐16A).11 The face and scalp may be involved, and granulomatous masses can be seen at these sites. Approximately 90% of patients with CMC also present with oral candidiasis. The oral manifestations may involve the tongue (Figure 4‐16B) and white plaque‐like lesions are seen in conjunction with fissures. CMC can occur as part of endocrine disorders, including hyperparathyroidism and Addison’s disease. Recent studies revealed that an impairment of interleukin‐17 (IL‐17) immunity underlies the development of CMC. Th17 cells produce IL‐17 and play an important role in host mucosal immunity to Candida. Impaired phagocytic function by neutrophilic granulocytes and macrophages caused by myeloperoxidase deficiency have also been associated with CMC.

Chédiak–Higashi syndrome, an inherited disease with a reduced and impaired number of neutrophilic granulocytes, lends further support to the role of the phagocytic system in candidal infections, as these patients frequently develop candidiasis. Severe combined immunodeficiency (SCID) syndrome is characterized by a defect in the function of the cell‐mediated arm of the immune system. Patients with this disorder frequently contract disseminated candidal infections. Thymoma is a neoplasm of thymic epithelial cells that also is associated with systemic candidiasis. Thus, both the innate and adaptive immune systems are critical to prevent the development of systemic mucocutaneous candidiasis.

Figure 4‐16 Chronic candidiasis of (A) dorsum of tongue and (B) fingernails of a patient with chronic mucocutaneous candidiasis.

Diagnosis and Laboratory Findings

The presence of candidal microorganisms as a member of the commensal flora complicates the discrimination of the normal state from infection. Candida cells can be found in 60% of people in numbers of up to 500 cfu/mL as normal commensals. However, in infection, these numbers may increase to over 10,000 cfu/mL and any increase to over 1000 cfu/mL may be seen in candidal infections. It is imperative that both clinical findings and laboratory data (Table 4‐5) are balanced in order to arrive at a correct diagnosis. Sometimes antifungal treatment has to be initiated to assist in the diagnostic process, with a good clinical response indicating a retrospective diagnosis. Smears (cytology) are useful for indicating hyphae, and salivary culture for indicating numerically raised counts. Swabs indicate neither hyphae nor counts, but can confirm the presence of raised amounts of Candida.

Smears from the infected area comprise epithelial cells, debris, and Candida. The material is fixed in isopropyl alcohol and air‐dried before staining with periodic acid–Schiff (PAS). The detection of several yeast organisms in the form of hyphae‐ or pseudohyphae‐like structures is usually considered a sign of infection, although these structures can occasionally be found in normal oral mucosa. This technique is particularly useful when pseudomembranous oral candidiasis and angular cheilitis are suspected (Table 4‐6). Cultivation of saliva, oral washings, or swabs are performed on Sabouraud agar and in the case of saliva or washings the cfu/mL can be determined (Table 4‐7). To discriminate between different candidal species, an additional examination can be performed on chromogenic agar (e.g., Pagano–Levin agar). Imprint culture technique can also be used where sterile plastic foam pads (2.5 × 2.5 cm) are moistened in Sabouraud broth and placed on the infected mucosal or denture surface for 60 seconds. The pad is then firmly pressed onto Sabouraud agar, which will be cultivated at 37 °C. The result is expressed as colony forming units per cubic milliliter (cfu/mL2). This method is a valuable adjunct in the diagnostic process of erythematous candidiasis and in denture stomatitis, where high counts will be found on the denture but not on the palate.

Table 4‐5 Routine tests for patients with suspected oral candidiasis.

| Smears (cytology) |

| Swabs |

| Culture of saliva (or saline rinses) for cfu/mL |

| Biopsies |

| Hematology |

|

|

| Immunology, endocrinology |

Table 4‐6 Summary of laboratory tests in relation to different types of oral candidiasis.

| Smear | Swab | Saliva cfu/mL |

Biopsy | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PC | + | ± | + | – |

| EC | + | ± | + | – |

| CAC | ± | + | + | – |

| AC | + | + | ± | – |

| CHC | + | ± | + | + |

| AAC | ± | + | + | – |

| MRG | + | ± | + | +* |

AAC, acute atrophic candidiasis; AC, angular cheilitis; CAC, chronic atrophic candidiasis; CHC, chronic hyperplasic candidiasis; EC, erythematous candidiasis; MRG, median rhomboid glossitis; PC, pseudomembranous candidiasis.

+ = useful; ± = sometimes useful; – = not useful; * = not usually necessary since MRG is diagnosed on clinical grounds.

In chronic plaque type and nodular candidiasis, cultivation techniques have to be supplemented by a biopsy and histopathologic examination (Table 4‐6). This examination is primarily performed to identify the presence of any epithelial dysplasia and to identify invading candidal hyphae by PAS staining (Figure 4‐10).

If clinical signs of Candida infection are not evident, then undertaking laboratory investigations may not be appropriate, and sometimes the clinical signs are so obvious (e.g., pseudomembranous candidiasis) that laboratory tests may not be needed and antifungal therapy may be initiated without confirmatory tests. Tests may also be helpful if the expected response to treatment does not materialize. These may include speciation and testing for antifungal sensitivity, especially for the azoles. Some species (e.g., C. krusei, C. glabrata) have natural resistance to azoles, and others may become resistant after previous exposure.

Management

Treatment for fungal infections, which usually includes antifungal regimens, will not always be successful unless the clinician addresses predisposing factors that may cause recurrence. Local factors are often easy to identify but sometimes not possible to reduce or eradicate. Antifungal drugs have a primary role in such cases. In smokers, cessation of the habit may result in disappearance of the infection even without antifungal treatment (Figure 4‐17). Superficial mucosal infections are often best treated with topical antifungals, whereas chronic hyperplasic types will respond best to systemic therapy. The most commonly used antifungal drugs belong to the groups of polyenes or azoles (Table 4‐8).

Polyenes such as nystatin and amphotericin are usually the first choices in treatment of primary oral candidiasis and are both well tolerated. Polyenes are not absorbed from the gastrointestinal tract and are not associated with development of resistance. They exert the action through a negative effect on the production of ergosterol, which is critical for the yeast’s cell membrane integrity. Polyenes can also affect the adherence of the fungi to epithelial cells.

Whenever possible, elimination or reduction of predisposing factors should always be the first goal for treatment of denture stomatitis as well as other opportunistic infections. This involves improved denture hygiene and a recommendation not to use the denture while sleeping. The denture hygiene is important to remove nutrients, including desquamated epithelial cells, which may serve as a source of nitrogen, which is essential for the growth of the yeasts. Denture cleaning also disturbs the maturity of a microbial environment established under the denture. As porosities in the denture can harbor microorganisms, which may not be removed by physical cleaning, the denture should be stored in antimicrobial solution during the night. Different solutions, including alkaline peroxides, alkaline hypochlorites, acids, and disinfectants, have been suggested. Chlorhexidine may also be used, but can discolor the denture and also counteracts the effect of nystatin.12

Surgical excision of type III denture stomatitis is sometimes advised in an attempt to eradicate microorganisms present in the deeper fissures of the granular tissue. However, this is neither sensible nor necessary, and it should not even be considered. Improved hygiene, better‐fitting dentures, and not wearing them overnight should clear the inflammation and edema sufficiently.

Table 4‐7 Candida Isolation in the clinic and quantification from oral samples.

Source: Adapted from Sitheeque MA, Samaranayake LP. Chronic hyperplastic candidosis/candidiasis (candidal leukoplakia). Crit Rev Oral Biol Med. 2003;14(4):253–267.

| Method | Main Steps | Advantages | Disadvantages |

|---|---|---|---|

| Smear | Scraping, smearing directly onto slide | Simple and quick | Low sensitivity |

| Salivary culture | Patient expectorates 2 mL saliva into sterile container; vibration; culture on Sabouraud agar by spiral plating; counting | Quantifies actual counts against normal range Useful to monitor response to therapy |

Longer chairside time; not useful for xerostomics Does not identify site of infection |

| Oral rinse | Subject rinses for 60 s with phosphate‐buffered saline at pH 7.2, and returns it to the original container; cultured and counted as in previous methods | Simple method Sensitive Normal ranges available |

Recommended in hyposalivation Does not identify site of infection |

| Impression culture | Maxillary and mandibular alginate impressions; casting in agar fortified with Sabouraud broth; incubation | Useful to determine relative distributions of yeasts on oral surfaces | Useful mostly as a research tool |

| Imprint culture | Sterile plastic foam pads moistened with Sabouraud broth, placed on lesion for 60 s; pad pressed on Sabouraud agar plate and incubated; colony counter used | Sensitive and reliable; can discriminate between infected and noninfected sites | Reading above 50 CFU/cm2 can be inaccurate Useful mostly as a research tool |

Figure 4‐17 Palatal erythematous candidiasis in a cigarette smoker (A) before treatment; (B) after treatment.

Topical treatment with azoles such as miconazole is the treatment of choice for angular cheilitis, often infected by both S. aureus and candidal strains. This drug has a biostatic effect on S. aureus in addition to the fungistatic effect (but also augments warfarin). Antiseptic ointment can be used as a complement to the antifungal drugs if Staphylococcus is suspected. If angular cheilitis comprises an erythema surrounding the fissure, a mild steroid ointment may be required in addition to the antifungal to suppress the inflammation. To prevent recurrences, treatment of the intraoral reservoir of Candida is essential and patients may benefit from applying a moisturizing cream, which may prevent new fissure formation.

Systemic azoles may be used for deeply seated primary candidiasis, such as chronic hyperplastic candidiasis and median rhomboid glossitis with a granular appearance, and for therapy‐resistant infections, mostly related to compliance failure. There are several disadvantages with the use of azoles. They are known to interact with warfarin, leading to an increased bleeding propensity. This adverse effect may also be present with topical application, as the azoles are fully or partly resorbed from the gastrointestinal tract. Development of resistance is particularly compelling for fluconazole in individuals with HIV disease. In such cases, ketoconazole and itraconazole have been recommended as alternatives. However, cross‐resistance has been reported between fluconazole on the one hand and ketoconazole, miconazole, and itraconazole on the other. The azoles are also used in the treatment of secondary oral candidiasis associated with systemic predisposing factors and for systemic candidiasis. Some suggested regimes for the treatment of local and systemic Candida infections are outlined in Table 4‐8.

Table 4‐8 Antifungal agents used in the treatment of oral candidiasis.

Adapted from Ellepola AN, Samaranayake LP. Oral candidal infections and antimycotics. Crit Rev Oral Biol Med. 2000;11(2):172–198.

| Drug | Form | Dosage | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|

| Amphotericin | Lozenge, 10 mg | Slowly dissolved in mouth 3–4 times/day after meals for 2 weeks minimum | Negligible absorption from gastrointestinal tract When given intravenously for deep mycoses may cause thrombophlebitis, anorexia, nausea, vomiting, fever, headache, weight loss, anemia, hypokalemia, nephrotoxicity, etc. |

| Oral suspension, 100 mg/mL | Placed in mouth after food and retained near lesions 4 times/day for 2 weeks | ||

| Nystatin | Cream | Apply to affected area 3–4 times/day | Negligible absorption from gastrointestinal tract Nausea and vomiting with high doses |

| Pastille, 100,000 U | Dissolve 1 pastille slowly after meals 4 times/day, usually for 7 days | ||

| Oral suspension, 100,000 U | Apply after meals 4 times/day, usually for 7 days, and continue use for several days after postclinical healing | ||

| Clotrimazole | Cream | Apply to affected area 2–3 times/day for 3–4 weeks | Mild local effects Also has antistaphylococcal activity |

| Solution | 5 mL 3–4 times/day for 2 weeks minimum | ||

| Miconazole | Oral gel

Cream |

Apply to affected area 3–4 times/day | Occasional mild local reactions Also has antibacterial activity Theoretically the best antifungal to treat angular cheilitis Interacts with anticoagulants (warfarin), terfenadine, cisapride, and astemizole Avoid in pregnancy and liver disease |

| Apply twice/day and continue for 10–14 days after lesion heals | |||

| Ketoconazole | Tablets | 200–400 mg tablets taken once or twice/day with food for 2 weeks | May cause nausea, vomiting, rashes, pruritus, and liver damage Interacts with anticoagulants, terfenadine, cisapride, and astemizole Contraindicated in pregnancy and liver disease |

| Fluconazole | Capsules | 50–100 mg capsules once/day for 2–3 weeks | Interacts with anticoagulants, terfenadine, cisapride, and astemizole Contraindicated in pregnancy and liver and renal disease May cause nausea, diarrhea, headache, rash, and liver dysfunction |

| Itraconazole | Capsules | 100 mg capsules daily taken immediately after meals for 2 weeks | Interacts with terfenadine, cisapride, and astemizole Contraindicated in pregnancy and liver disease May cause nausea, neuropathy, or rash |

Prognosis of oral candidiasis is good when predisposing factors associated with the infection are reduced or eliminated. Persistent chronic plaque type and nodular candidiasis have been suggested to be associated with an increased risk for malignant transformation compared with leukoplakia not infected by candidal strains. Patients with primary candidiasis are also at risk if systemic predisposing factors emerge. For example, patients with severe immunosuppression, as seen in conjunction with leukemia and AIDS, may encounter disseminating candidiasis with a fatal course.13

Oral Hairy Leukoplakia

Oral hairy leukoplakia (OHL) is the second most common HIV‐associated oral mucosal lesion. OHL has been used as a marker of disease activity, since the lesion is associated with low CD4+ T lymphocyte counts.14 It is caused by concurrent infection with the Epstein–Barr virus (EBV). The lesion is strongly associated with HIV disease, but other states of immune deficiencies, such as those caused by immunosuppressive drugs and cancer chemotherapy, have also been associated with OHL.

Etiology and Pathogenesis

OHL appears to be an EBV‐induced lesion in patients with low levels of CD4+ T lymphocytes. Antiviral medication, which prevents EBV replication, is curative and lends further support to EBV as an etiologic factor. There is also a correlation between EBV replication and a decrease in the number of CD1a+ Langerhans cells, which, together with T lymphocytes, are important cell populations in the cellular immune defense of the oral mucosa.15

Epidemiology

The prevalence figures for OHL depend on the type of population investigated and vary around the world. Prior to the ART era, the mean prevalence was 25% of people living with HIV, but this figure has decreased considerably after the introduction of more effective therapies.16 In contrast, patients who develop AIDS have an increased prevalence of greater than 50%. The prevalence in children is lower compared with adults and has been reported to be around 2%.17 The condition is more frequently encountered in men, but the reason for this predisposition is not known. A correlation between smoking and OHL has also been observed.18

Clinical Findings

OHL is frequently encountered bilaterally on the lateral borders of the tongue (Figure 4‐18), but may also be observed on the dorsum and in the buccal mucosa.19 The typical clinical appearance is vertical white folds oriented as a palisade along the borders of the tongue. The lesions may also be seen as white and somewhat elevated plaque, which cannot be scraped off. OHL is asymptomatic, although symptoms may be present when the lesion is superinfected with candidal strains. As OHL may present in different clinical forms, it is important always to consider this mucosal lesion whenever the border of the tongue is affected by white lesions, particularly in immunocompromised patients.

Diagnosis

A diagnosis of OHL is usually based on clinical characteristics, but histopathologic examination and detection of EBV can be performed to confirm the clinical diagnosis (Table 4‐9). It may most easily be confused with chronic trauma to the lateral borders of the tongue, but in that instance the corrugations are horizontal, not vertical.

Figure 4‐18 Hairy leukoplakia at the left lateral border of tongue in an AIDS patient showing vertical keratotic corrugations.

Pathology

The histopathology of OHL is characterized by hyperkeratosis, often with a chevron‐pattern surface and acanthosis. Hairy projections are common, which is reflected in the name given to this disorder. Koilocytosis, with edematous epithelial cells and pyknotic nuclei, is also a characteristic histopathologic feature. The complex chromatin arrangements may mirror EBV replication in the nuclei of koilocytic epithelial cells. Candidal hyphae surrounded by polymorphonuclear granulocytes are a common feature. The number of Langerhans cells detected by immunostaining is considerably reduced. Mild subepithelial inflammation may also be observed. EBV can be detected by in situ hybridization or by immunohistochemistry. Exfoliative cytology may be of value and can serve as an adjunct to biopsy.

Management

OHL can be treated successfully with antiviral medication, but this is not often indicated, as this disorder is not associated with adverse symptoms. In addition, the disorder has also been reported to show spontaneous regression. OHL is not related to increased risk of malignant transformation. Medication with ART has reduced the number of OHL to a few percent in HIV‐infected patients.20

ORAL POTENTIALLY MALIGNANT DISORDERS

Oral Leukoplakia

Definitions

Leukoplakia is defined as a white plaque of questionable risk for malignant transformation having excluded other known white lesions or disorders that carry no increased risk for cancer. Leukoplakia is thus a diagnosis of exclusion. Erythroplakia is a fiery red patch that cannot be characterized clinically or pathologically as any other definable disease. Both those diagnoses thus require exclusion of other similar‐looking lesions of known causes or mechanisms before being applied.21

Table 4‐9 Features of the diagnosis of oral hairy leukoplakia.

| Provisional diagnosis |

| Characteristic gross appearance of bilateral vertical corrugations on sides of tongue, with or without responsiveness to antifungal therapy |

| Presumptive diagnosis |

| Light microscopy of histologic sections revealing hyperkeratosis, koilocytosis, acanthosis, and absence of inflammatory cell infiltrate, or light microscopy of cytologic preparations demonstrating nuclear beading and chromatin margination |

| Definitive diagnosis |

| In situ hybridization of histologic or cytologic specimens revealing positive staining for Epstein–Barr virus DNA, or electron microscopy of histologic or cytologic specimens showing herpesvirus‐like particles |

By far the majority of white and red lesions are benign. However, the two conditions with the greatest malignant potential in the oral cavity are leukoplakia (white plaque) and erythroplakia (red plaque). The relative importance of one versus the other is that leukoplakia is very common and can sometimes transform into cancer, whereas erythroplakia is rather uncommon but frequently represents a precursor to cancer. There is also a term erythroleukoplakia (nonhomogeneous, speckled leukoplakia), which has both white and red areas, and the sinister nature of erythroleukoplakia and erythroplakia should be considered alike.

Etiology and Pathogenesis

By definition, leukoplakia is idiopathic, having excluded white patches of known etiology. The exception to this rule is that smoking is recognized as an etiological or exacerbating factor and smoker’s keratosis may regress when the irritant is removed (see later).22 As smoking cessation can effectively reverse many tobacco‐associated leukoplakia, appreciating its etiology and acting appropriately form the best approach to prevent oral cancer.22

Hairy leukoplakia is not considered a true leukoplakia, since the etiology and infective agent (EBV) are known and the risk of malignant transformation appears to be almost nonexistent.

The development of oral leukoplakia and erythroplakia as potentially malignant lesions involves different genetic events. This notion is supported by the fact that markers of genetic defects are differently expressed in different leukoplakias and erythroplakias.23–25 Activation of oncogenes and deletion and injuries to suppressor genes and genes responsible for DNA repair will all contribute to a defective functioning of the genome that governs cell division. Following a series of mutations, a malignant transformation may occur. For example, carcinogens such as tobacco may induce hyperkeratinization, with the potential to revert following cessation, but at some stage mutations will lead to unrestrained proliferation and cell division.

Epidemiology

The prevalence of oral leukoplakia varies among scientific studies. A comprehensive global review points at prevalences between 1.5% and 2.6%.26 Most oral leukoplakias are seen in patients beyond the age of 50 and are infrequently encountered below the age of 30. In population studies, leukoplakias are more common in men, but a slight majority for women has been found in some studies.27

Clinical Findings

Oral leukoplakia is defined as a white plaque of questionable risk having excluded (other) known diseases or disorders that carry no increased risk for cancer. This disorder can be further divided into a homogeneous and a nonhomogeneous type. The typical homogeneous leukoplakia is clinically characterized as a white, often well‐demarcated plaque with a similar reaction pattern throughout the lesion (Figure 4‐19). Some lesions are uniformly presented in the entire area, but the surface texture can vary, even in a single case, from smooth and thin to a leathery appearance with surface fissures sometimes referred to as “cracked mud.” Thus, different thicknesses and textures can, in the absence of red areas and frank verruciform parts, still allow styling leukoplakia as homogeneous. The demarcation is usually distinct, which is different from an oral lichen planus (OLP) lesion, where the white components have a more diffuse transition to the normal oral mucosa. Another difference between these two lesions is the lack of a peripheral erythematous zone in homogeneous oral leukoplakia. The lesions are asymptomatic.

The term “nonhomogeneous” is somewhat less precise. The term is ascribed to lesions with two different features, usually having both red and white areas (Figure 4‐20A), but also to all those without redness but containing verruciform exophytic elements. Due to the combined appearance of white and red areas, the nonhomogeneous oral leukoplakia has also been called erythroleukoplakia and speckled leucoplakia (Figure 4‐20B). The clinical manifestation of the white component may vary from large white verrucous areas to small nodular structures. If the surface texture is homogeneous but contains verrucous, papillary (nodular), or exophytic components, the leukoplakia is also regarded as nonhomogeneous.

It should be stressed that there is a marked difference in malignant potential between those two subtypes of nonhomogeneous leukoplakia. Those with red areas should be considered as an early cancer unless histopathologically proven otherwise. Those without red areas still have potential for malignant transformation, but less so. Oral leukoplakias, where the white component is dominated by papillary projections, similar to oral papillomas, are referred to as verrucous or verruciform leukoplakias.28

Figure 4‐19 Clinical variations of homogeneous leukoplakias. (A) A homogeneous leukoplakia at the left buccal mucosa, (B) right side of tongue, and (C) upper buccal sulcus, which transformed into a squamous cell carcinoma two years later.

Figure 4‐20 Nonhomogeneous leukoplakias of the floor of the mouth, which both transformed into squamous cell carcinomas. (A) Nonhomogeneous leukoplakia in a heavy smoker at the floor of the mouth. The left part of the lesion has a speckled appearance. (B) Nonhomogeneous leucoplakia showing a speckled appearance centrally, which transformed into squamous cell carcinoma over two years.

Oral leukoplakia may be found at all sites of the oral mucosa. The floor of the mouth and the lateral borders of the tongue are high‐risk sites for malignant transformation (Figure 4‐21). These sites have also been found to have a higher frequency of loss of heterozygosity compared with low‐risk sites. However, the size of the lesion and the homogeneous/nonhomogeneous pattern are also decisive characteristics for the prognosis, whatever the site.

Proliferative Verrucous Leukoplakia

Proliferative verrucous leukoplakia (PVL) is an uncommon and serious condition where the pattern of clinical behavior does not match the histologic features. Diagnosis cannot usually be established at a single consultation. Histologically the lesion may appear benign, but clinically it behaves as a malignancy with gradually spreading leukoplakia, often gingivally. Oral leukoplakias with this clinical appearance but with a more aggressive proliferation pattern and high recurrence rate are designated as PVL (Figure 4‐22).29 This lesion may start as a homogeneous leukoplakia, but over time develops a verrucous appearance containing various degrees of dysplasia. PVL is usually encountered in older women, and the lower gingiva is a predilection site. The malignant potential is very high, and verrucous carcinoma or squamous cell carcinoma may be present at the primary examination. As the reaction pattern is similar to what is seen in oral papillomas, PVL has been suspected to have a viral etiology, although an association has not been confirmed.30

Figure 4‐21 The patient with floor‐of‐mouth nonhomogeneous leukoplakia (Figure 4‐20A) did not attend follow‐up visits for three years and developed a squamous cell carcinoma.

Figure 4‐22 A proliferative verrucous leukoplakia progressively extending from the buccal mucosa, across the gingiva to the ventral surface of the tongue in a 48‐year‐old female.

Erythroplakia

Epidemiology

Oral erythroplakia is not as common as oral leukoplakia, and the prevalence in adults has been estimated to be in the range of 0.02% to 0.1%. The sex distribution is reported to be equal.

Oral erythroplakia has not been studied as extensively as oral leukoplakia, presumably because it is less common. Erythroplakia is initially a clinical diagnosis. It is defined as a red lesion of the oral mucosa that excludes other known pathologies (Figure 4‐23). It comprises an irregular red lesion that is frequently observed with a distinct demarcation against the normal‐appearing mucosa, sometimes with velvety granular surface texture.31–33 Clinically, erythroplakia is different from erythematous OLP, as the latter has a more diffuse border and is surrounded by white reticular or papular structures. Erythroplakia is usually asymptomatic, although some patients may experience a burning sensation in conjunction with food intake.

It has been reported that 91% of histologically assessed homogeneous erythroplakias showed invasive carcinoma or carcinoma in situ, and in 9% there was moderate to severe dysplasia.31 Another study showed severe dysplasia and frank carcinoma in 75% and mild to moderate dysplasia in 25%.33 Thus, all erythroplakias should be considered as sinister. Any red mucosal lesion without an apparent local cause or not fitting into other known red lesions, and not regressing following removal of possible cause or two weeks of treatment, should be considered a cancer unless histologically proven otherwise.

Figure 4‐23 An erythroplakia on the upper alveolar ridge. Later on the patient developed a squamous cell carcinoma.

A special form of erythroplakia has been reported that is related to reverse smoking of chutta, predominantly practiced in India. The lesion comprises well‐demarcated red areas in conjunction with white papular tissue structures. Ulcerations and depigmented areas may also be a part of this particular form of oral lesion.

Diagnosis

The diagnostic procedure of oral leukoplakia and erythroplakia is identical. The provisional diagnosis is based on the clinical observation of a white or red patch that is not explained by a definable cause, such as trauma. If trauma is suspected, the cause, such as a sharp tooth or restoration, should be eliminated. If healing does not occur in two weeks, a tissue biopsy is essential to rule out malignancy. Realistically, differential diagnosis often requires considerable experience. As can be observed from referrals, clinicians not trained in an oral medicine specialty will rarely be able to perform clinical “fine print” distinction between various white lesions. Any similar white mucosal area will likely be initially indiscriminately proclaimed as “leukoplakia” instead of what it really may be (frictional hyperkeratosis, plaque‐like lichen planus, habitual cheek biting, etc.). Sometimes there are cases when even specialists struggle with a final diagnosis, or change it over time.

Biopsies

Excisional biopsy is generally recommended if the leukoplakia diameter is less than 30 mm and the location allows (e.g., out of fine sublingual structures or not associated with marginal gingiva). Otherwise, in larger lesions incisional biopsies should be undertaken, sometimes from several sites. Selecting the appropriate site that will best represent the most severe aspect is of paramount importance, as underdiagnosing the lesion may be dangerous. New biopsies should be taken if new clinical features emerge. Following five years of no relapse, self‐examination may be a reasonable approach.

Oral Leukoplakia and Erythroplakia: Pathology

The clinical appearance is a poor predictor of the histologic characteristics or behavior of oral leukoplakia, with the exception of the nonhomogeneous (speckled, erythroleukoplakia) type, which often displays a spectrum of occurrences from any degree of dysplasia to cancer. The biopsy should include representative tissue of the different clinical patterns. Hyperkeratosis without any other features of a definable diagnosis is compatible with homogeneous oral leukoplakia. If the histopathologic examination leads to another definable lesion, the definitive diagnosis will be changed accordingly. However, there is no uniform depiction of an oral leukoplakia and the histopathologic features of the epithelium may include hyperkeratosis, atrophy, and hyperplasia with or without dysplasia. When dysplasia is present, it may vary from mild to severe. Dysplasia may be found in homogeneous leukoplakias, but is much more frequently encountered in nonhomogeneous leukoplakias and in erythroplakias.

Epithelial dysplasia is defined in general terms as a precancerous lesion of stratified squamous epithelium characterized by cellular atypia and loss of normal maturation short of carcinoma in situ (Figure 4‐24). Carcinoma in situ is defined as a lesion in which the full thickness of squamous epithelium shows the cellular features of carcinoma without stromal invasion.34 A more detailed description of the features of epithelial dysplasia is presented in Table 4‐10. The prevalence of dysplasia in oral leukoplakias varies from 1% to 30%, presumably due to various lifestyle factors involved and due to subjectivity in the histopathologic evaluation. The majority of erythroplakias display an atrophic epithelium with dysplastic features. The significance of epithelial dysplasia for predicting future development of oral cancer is not always clear.

Oral Leukoplakia and Erythroplakia: Management

There are two key unanswered questions that clinicians would consider the most challenging regarding management of oral leukoplakia. The first is how to estimate the risk of a particular case transforming into oral squamous cell carcinoma; that is, to assess the likelihood of malignant transformation and how soon it may happen. Clinical and histopathologic features are somewhat helpful, but the information obtained from them has limitations. In spite of major scientific efforts, universal markers that reliably and efficiently identify lesions with higher risk and that could predict their malignant transformation have not been discovered.35,36

Figure 4‐24 Histopathology of a leukoplakia with several characteristics of dysplasia in the oral epithelium (Table 4‐9): drop‐shaped rete ridges, nuclear hyperchromatism, presence of more than one layer of cells having a basaloid appearance, and irregular epithelial stratification.

Table 4‐10 Criteria used for diagnosis of epithelial dysplasia.

| Loss of polarity of basal cells |

| Presence of more than one layer of cells having a basaloid appearance |

| Increased nuclear–cytoplasmic ratio |

| Drop‐shaped rete ridges |

| Irregular epithelial stratification |

| Increased number of mitotic figures |

| Mitotic figures that are abnormal in form |

| Presence of mitotic figures in the superficial half of the epithelium |

| Cellular and nuclear pleomorphism |

| Nuclear hyperchromatism |

| Enlarged nuclei |

| Loss of intercellular adherence |

| Keratinization of single cells or cell groups in the prickle cell layer |

Since leukoplakias are asymptomatic, the main purpose of treatment is to prevent the development of cancer (or sometimes esthetics). Thus, a key question is whether anything can be done so that leukoplakia does not transform to cancer. Several approaches have been suggested, including chemoprevention with nonsteroidal anti‐inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) and metformin, but neither medications nor surgical approaches seem to be effective in preventing cancer development in patients with leukoplakia.37–39

As we do not have answers to those two pertinent questions, management of leukoplakia follows certain non‐evidence‐based protocols, but optimal management approaches are on a case‐by‐case basis and sometimes require numerous, lifelong, and frequent follow‐up visits, including repeated biopsies.40 Every oral health professional has a major role in identifying and diagnosing leukoplakia. Due to its unpredictable nature and the fact that even specialists find leukoplakia challenging, once it is suspected it is best referred to an oral medicine specialist. Oral medicine specialists will monitor patients closely and in a structured manner. Furthermore, specialists in hospitals have direct access to other clinicians, including head and neck surgeons, in case malignancy occurs and aggressive surgical intervention is required.

In contrast to leukoplakias, where close monitoring for years is a sensible alternative to surgical treatment, in erythroplakias biopsy and then excision constitute the normal recommended approach. Since such a high proportion of erythroplakias show severe dysplasia or carcinoma in situ on biopsy, excision usually follows. Usually, erythroplakias are not extensive, and thus neither will the surgery be.

In general, clinical management of leukoplakia relates to a combination of clinical (site, homogeneity, size, behavior) and histologic features (presence and degree of dysplasia and inflammation). While those leukoplakias that are homogeneous, stable, on lower‐risk sites such as the buccal mucosa and show no dysplasia, can be reviewed annually (assuming no change in clinical characteristics), those showing clinical characteristics of mixed appearance, on high‐risk sites, changing in size, in smokers, and histologically showing a degree of dysplasia will need to be reviewed more regularly. It can be deduced that a reproducible risk score from this combination of features would be very helpful for clinicians. An algorithm for management is shown in Figure 4‐25.

If dysplasia is not present, follow up at six‐month intervals is recommended. In case of dysplasia, the decision whether to surgically remove the whole lesion or not will depend upon its severity and the size and location of the lesion. Mild dysplasia may regress, and thus watchful waiting is appropriate. However, moderate to severe dysplasia is not likely to regress, but the rate of its progression cannot be estimated. In such cases, the premalignant site irrespective of surgical excision should be reexamined every three months, at least for the first year. If the lesion does not relapse or change in clinical pattern, the follow‐up intervals may be extended to once every six months, with the patient advised with regard to self‐examination. Oral leukoplakia is a lesion with an increased risk of malignant transformation, which has great implications for the management of this oral mucosal disorder (Figure 4‐25

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses