This article explores the psychosocial and economic implications of cancer and their relevance to the clinician. After a general overview of the topic, the authors focus on aspects of particular importance to the dental professional, including the psychosocial and economic implications of the oral complications of cancer and its therapy, head and neck cancers, and special issues among children with cancer and cancer survivors.

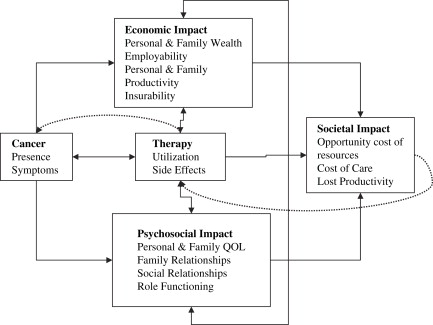

From the moment of diagnosis, the presence of cancer has a profound psychologic impact on the qualify of life (QOL) of patients and their families, on family and social relationships, and on role functioning ( Fig. 1 ). These effects are magnified by therapy, which consumes the intellectual and emotional energy of patients and their families and leads to side effects that further hamper role functioning and QOL. With regard to the economic impact, the mere diagnosis of cancer reduces employability and insurability, and treatment and its side effects consume personal and family wealth and reduce productivity. Economic challenges reduce QOL and strain family relationships while altered role functioning and poor QOL reduce employability and productivity.

Intensive and often prolonged cancer treatments may strain already limited health care resources such as hospital beds, personnel, and blood products for the management of anemia and thrombocytopenia. This “opportunity cost” of cancer also applies to health care finances. Assuming that a finite amount of money is available for health care in any society, the expenditure on cancer care reduces the opportunity to spend money on other health care priorities. Additionally, society, particularly employers, must address the loss of productivity of cancer patients and their employed family members who often must miss work for caregiving. Finally, the years of life lost to cancer mortality affect both economic (eg, job-related productivity) and social aspects of society (eg, benefits from volunteer activities, parenting).

This article explores the psychosocial and economic implications of cancer and their relevance to the clinician. After a general overview of the topic, we focus on aspects of particular importance to the dental professional, including the psychosocial and economic implications of oral complications of cancer and its therapy and of head and neck cancers, and special issues among children with cancer and cancer survivors.

Overview of the psychosocial and economic impact of cancer

Psychosocial impact on quality of life, family relationships, functional status, and social functioning

QOL is a multidimensional construct including mental and emotional well-being, physical limitations, the availability of appropriate treatment, family and social relationships, and finances. The dimensions are intertwined, and each is important to cancer patients for maximal functioning. QOL is affected by the type and extent of cancer and by the chronic concerns of patients that their cancer will recur or progress .

QOL is a frequent topic of concern among those who care for chronically ill patients. Quantifying QOL is important because a less-than-optimal QOL can severely compromise an individual’s ability to handle stressful situations and follow treatment or supportive care schedules . Historically, QOL was regarded as subjective and difficult to quantify, and the measure of a patient’s well-being was thought to extend beyond laboratory values. Later, tools were designed to quantify the QOL of cancer patients, and further research found that QOL was a stronger predictor of survival than other clinical measures such as performance status .

Not surprisingly, QOL scores are inversely related to cancer stage. Patients with more advanced disease tend to have lower (poorer) QOL scores. In a large trial, patients with local or stage 1 disease reported a QOL score of 89.7 compared with 80.7 among patients with stage 4 or advanced disease . Physical and functional well-being were the primary contributors to the lower scores among patients with advanced disease, whereas social and emotional well-being were similar across all cancer stages.

Several instruments are used to assess QOL, either by a composite appraisal encompassing many dimensions or by singling out one element, such as anxiety or depression. Tools designed for use in patients with chronic disease, such as the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) and the Utrecht Coping List , also provide a reliable assessment of the mental well-being and coping skills of a cancer patient. Many studies have evaluated QOL in patients involved in clinical trials by use of a comprehensive measure such as the European Organization for the Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC) Quality-of-Life questionnaire . The Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy (FACT/FACIT) instrument is often used during and after treatment . Both tools are widely used with modules for specific cancers that evaluate distinct symptoms such as fatigue.

These instruments identify which dimensions detract from QOL but do not identify specific unmet needs . To assess the latter, several tools have been adapted, such as the Kingston Needs Assessment–Cancer Questionnaire and the Supportive Needs of Cancer Survivors (SNCS) .

Table 1 provides an overview of a variety of tools. The King’s College of the University of London Patients’ Needs Assessment Tools in Cancer Care: Principles & Practice July 2005 provides comprehensive descriptions of additional instruments . These tools are important because the perceptions of unmet needs of patients and their caregivers may be quite different. In a recent study by Snyder and colleagues , patients reported that needs assessment instruments would be most useful in assisting their caregivers in providing the assistance they most wanted. In contrast, caregivers thought the composite tools including symptom information would be most useful. Interestingly, caregivers ranked pain control as the patients’ highest priority while patients ranked pain control 15th among their top 20 concerns, with their most important concern being obtaining information about possible treatment options and self-help measures.

| Instrument | Origin | Length: focus of instrument |

|---|---|---|

| Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy (FACT), now named Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapy (FACIT) | Cella (1993) Renamed in 1997 |

|

| COPE Questionnaire | Carver (1989) Renamed in 1997 | 14 items: ability and strategies for coping with cancer |

| Profile of Mood States (POMS), originally named Psychiatric Outpatient Mood Scales | McNair (1964) Revised by McNair (1971) | 65 scales (emotional distress in six areas): tension-anxiety, depression-dejection, anger-hostility, fatigue, vigor, confusion-bewilderment, total mood disturbance |

| Impact of Events Scale (IES) | Horowitz (1979) | 15 items: stress; intrusive symptoms (thoughts, feelings, nightmares); avoidance symptoms (avoidance of feelings, situations, ideas, lack of responsiveness) |

| European Organization for the Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC) Quality-of-Life | Study Group, Aaronson (1993) |

|

| Supportive Care Needs Survey (SCNS) | Bonevski and the Supportive Care Review Group (2000) | 59 items: cancer patients’ needs and degree to which needs have been met |

| Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) | Zigmond and Snaith (1983) | 10 items: screening tool for anxiety and depression |

| Social Support List Interactions (SSL-I) Short Form (SSL12-I) | van Sonderen (1991) Dutch Kempen (1995) English |

|

| Utrecht Coping List | Schreurs (1993) | 17 items: problem-solving, seeking support, coping behavior; active, avoidance, palliative and religious |

| Cancer Locus of Control Scale (CLOC) | Pruyn et al (1988) | 13 items: measures of internal control over disease cause and course (7 items); religious control (3 items); family, health care providers, friends control (3 items) |

| Center for Epidemiologic Studies-Depression (CES-D) | Radloff (1977) | 20 items: self-reported depression on scale 0 (fewer) to 60 (more) symptoms of depression |

| Kingston Needs Assessment-Cancer | Davidson (2003) | 52 items: adequacy of supportive services for symptom control, information needs, support service needs, overall experience at the facility, coordination of care |

Economic impact on health care costs, employability, productivity, and insurability

The overall costs for cancer that were borne by patients, their families, the health care system, and American society are estimated to have been nearly $206.3 billion in 2006, a substantial financial burden that is expected to increase over the next decade as cancer surpasses heart disease to become the nation’s leading cause of death . The following section discusses the impact of cancer on patients’ personal and family wealth, insurability, employability, and productivity, as well as the financial impact of the disease on society.

Economic impact of cancer on patients and families

Cancer poses an enormous financial burden on patients and their families, particularly on society’s most economically and socially vulnerable groups such as low-income and uninsured families. In a national survey of elderly Americans, low-income patients undergoing cancer treatment spent approximately 27% of their annual income on out-of-pocket medical expenses . In addition, a recent survey of households affected by cancer showed that nearly half who did not have consistent health insurance during cancer treatment reported using all or most of their savings to pay for cancer care. Twenty-seven percent had to delay or forgo cancer treatment because of the costs, and 6% filed for personal bankruptcy .

The national survey of people affected by cancer has also shed light on how a cancer diagnosis can affect a patient’s ability to acquire or maintain health insurance. About 6% of the affected patients lost their health insurance as a result of being diagnosed with cancer, and 11% reported being unable to buy health insurance because of having cancer . Furthermore, even those without problems maintaining their health insurance faced a number of billing and cost issues; nearly 25% reported that their insurance provider paid less than expected for a medical bill, 10% reached the policy’s limits for cancer treatment, and 8.3% were unable to obtain a specific type of treatment because of insurance issues .

Cancer also affects the employability and productivity of patients and their families. As many as 19% of the households affected by cancer reported that their experience with the disease caused someone in the household to lose or change jobs or to work fewer hours . In addition, the results of a national survey to determine the effects of commonly occurring chronic conditions on work in the adult population demonstrated that cancer was associated with the highest reported rate of work impairment and the largest number of impaired work days of all conditions . A study by Yabroff and colleagues showed that the estimated cost for the cancer patient’s time spent traveling, waiting for appointments, and receiving services or procedures during the first 12 months after diagnosis was as much as $5605. In pediatric cancers, the impact of the disease on family productivity can be even more dramatic, because the poor health of the child and the time demands associated with the cancer care often force one parent to quit working, which further compromises the income of these families .

Societal impact of cancer

The financial consequences of cancer extend to the whole health care system and society at large. In 2006, the National Institutes of Health estimated that the aggregate costs of cancer treatment in the United States totaled $78.2 billion, a cost largely borne by private health plans and government programs . Cancer currently accounts for 4.7% of the national health expenditure and ranks first as the most expensive per-patient condition in the nation, consuming valuable resources that could potentially be allocated to other health priorities . The financial impact of cancer on businesses results from increasing health insurance premiums and reduced productivity of affected employees or family members. Additionally, employers incur costs associated with the temporary or permanent replacement of employees with cancer or family members who serve as caregivers. In 2006, the indirect morbidity cost of lost productivity due to cancer in the United States is estimated to have been nearly $17.9 billion, whereas the cost of lost productivity due to premature cancer death was estimated at $110.2 billion . This financial burden will escalate as the number of cancers increases among aging baby boomers and those who adopt unhealthy lifestyles.

The psychosocial and economic burden of oral complications of cancer and cancer therapy

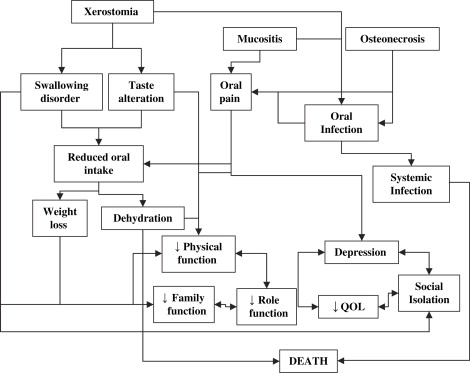

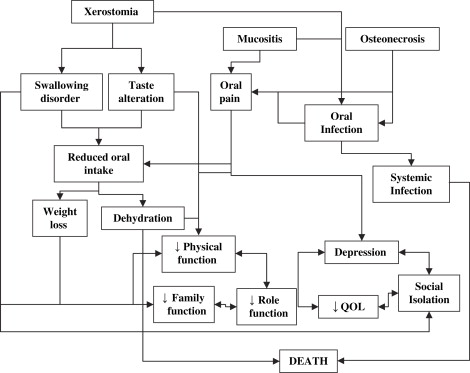

Although they are often described in the literature as separate clinical entities, the oral complications of cancer and its therapy are interrelated. For this reason, they share not only clinical characteristics but also clinical, functional, psychosocial, and economic outcomes ( Fig. 2 ).

Although oral complications can be debilitating and costly, they are rarely fatal. Systemic infections are notable exceptions to this rule, as is malnutrition which, through its association with a poor response to therapy, can also affect survival . The focus herein is on the intermediate outcomes of oral complications, that is, weight loss, family and role functioning, QOL and cost, and their interrelationships, rather than on ultimate outcomes such as mortality. The intermediate outcomes are shared to varying degrees by the complications discussed next.

Oral pain in some cases is a primary symptom of oral cavity and oropharyngeal tumors; in other cases it is a complication of therapy (see the articles by Clark, Ram, and Lalla and colleagues elsewhere in this issue). It is among the defining symptoms of oral mucositis but is also a prominent feature of oral cavity infections and osteonecrosis of the jaw . The initial approach to oral pain should involve the prescription of the least potent agent that is effective. Among patients with severe pain, more expensive analgesics may be required . Some patients may even require costly hospitalization and the delivery of opioids by a patient-controlled analgesia pump. Regardless of its cause, oral pain leads to reduced functional status, particularly with respect to eating, swallowing, and communication, with far reaching clinical, psychosocial, and economic implications. The inability to eat or swallow leads to weight loss and the need for dietary supplements, total parenteral nutrition through central venous catheters, or gastrostomy tube insertion for nutrition. Equally important, disturbances in the ability to talk and eat may lead to depression and social isolation at a time when patients most need the support of family and friends.

Oral mucositis is a common and debilitating complication of antineoplastic therapy and a common cause of oral pain . It occurs in virtually all patients who receive radiotherapy for oral cavity and oropharyngeal cancers and in more than 50% of those treated for hypopharyngeal and laryngeal cancer . In the latter population, the incidence of laryngeal mucositis is probably higher, although this has not been systematically studied owing to difficulties of examining these sites. In the head and neck cancer population, mucositis is associated with a high frequency of pain, dysphagia, and weight loss . These outcomes lead to increased requirements for gastrostomy tube insertions, hospitalizations, and an incremental cost of $1700 to $6000 per patient depending on the grade of mucositis . The risks and the severity of the adverse clinical and economic outcomes of radiation are increased by concomitant administration of chemotherapy and by accelerated schedules . For an in-depth review of oral mucositis, the reader is referred to the article by Lalla and colleagues elsewhere in this issue.

Amifostine is a radioprotector used to decrease the side effects of radiation. Its efficacy in reducing mucositis is debated. In a large phase III trial evaluating the efficacy of amifostine in xerostomia reduction for patients receiving radiation to the head and neck, amifostine was not believed to affect the incidence of mucositis, but mucositis was not the primary endpoint of this study . In contrast, in a small randomized clinical trial, the use of amifostine to reduce chemoradiation-induced mucositis and its adverse intermediate outcomes (infection, reduced alimentation, hospitalization) was shown to reduce the cost of supportive care, even after accounting for the acquisition price of the drug . Among patients receiving multicycle chemotherapy for ovarian cancer, amifostine use cost $36,161 per quality adjusted life-year gained . In contrast, a Cochrane review suggested only minimal benefit from use of amifostine .

Among patients who undergo hematopoietic cell transplantation (HCT), the risk of oral mucositis is high depending on the mucotoxicity of the conditioning regimen and whether total body irradiation is prescribed . In the HCT population, mucositis has been associated with poor clinical outcomes and increased costs . The use of palifermin to reduce the incidence of mucositis and its subsequent outcomes has been shown to be cost neutral in an economic study of clinical trial data from patients who received highly mucotoxic conditioning regimens including total body irradiation ; however, its cost-effectiveness has not been studied in other more common HCT settings.

Among patients who receive multicycle chemotherapy without radiation, the risk of oral mucositis varies depending on the regimen received, ranging from little or no risk to more than 50% with some regimens . When mucositis occurs, it is associated with increased risks of weight loss, infections, and hospitalization and an incremental cost of $3000 to $6000 per cycle depending on mucositis grade . Regardless of its cause, the ulceration that characterizes severe oral mucositis provides a portal of entry for microorganisms and the potential for local and systemic infection.

The presence of oral infection is an ominous clinical sign among patients with cancer (see the article by Treister and colleagues elsewhere in this issue) because potentially fatal systemic infections may ensue, particularly during periods of neutropenia . In addition to their clinical implications, these infections reduce QOL and increase cost. Antimicrobial agents are the first expense, and the need for antimicrobials is often accompanied by the need for pain medication. Pain leads to corresponding poor oral intake, weight loss, and the need for nutritional supplements . In cases in which systemic infection develops, intravenous antimicrobial agents with hospitalization may be required. Among HCT recipients, mucositis-associated bacteremias caused by gram-positive bacteria (ie, viridans streptococci , Staphylococcus aureus ) are potentially fatal and contribute to increased length of stay and cost of care . New and reactivated herpetic oral infections are among the most painful of oral infections; they contribute significantly to reduced QOL and to costs of treatment . Among bone marrow transplant recipients, dissemination of new or reactivated infections is avoided by prophylactic decontamination, typically with antiviral agents at a cost of $5 to $8 per patient per day .

Oral pain, infection, and mucositis occur acutely in close temporal proximity to treatment (and to each other). Most instances resolve within 2 to 6 months after treatment is discontinued, although their outcomes, in particular weight loss, often persist more than 6 months after treatment. In contrast, xerostomia, dysgeusia, dysphagia, and osteoradionecrosis, although more severe during treatment, often become chronic problems.

Among the persistent complications of cancer therapy, xerostomia (salivary hypofunction) is a major contributor to reduced function, poor QOL, and high costs . It is a common side effect of radiation for head and neck cancer, and the dose threshold is a subject of controversy . To the extent that intensity modulated radiation therapy (IMRT) spares the salivary glands, the risk and severity of xerostomia hyposalivation appear to be reduced, and recovery over time may occur . Hyposalivation increases swallowing abnormalities and altered taste, resulting in poor nutrition, weight loss, and the costs related to management of poor nutrition . It may also compromise vocal function .

Although it is often considered a complication of head and neck radiation, severe xerostomia was found to be the third most distressing symptom in a study of patients with advanced cancer who had received chemotherapy or analgesics . Treatment for xerostomia and hyposalivation may be as inexpensive as sugarless gum; however, in severe and prolonged cases, pharmacologic sialagogues such as pilocarpine and symptomatic treatment may be necessary at a cost exceeding $100 per month . Professional organizations have recommended that amifostine may be considered for the prevention or reduction of xerostomia and hyposalivation among patients who undergo fractionated head and neck radiotherapy . This radiotherapy protectant has been shown to be effective but is costly.

Alterations of taste that occur after chemotherapy and radiotherapy have important implications for the maintenance of nutritional status. These alterations contribute to poor appetite, lower consumption overall, and lower consumption of protein in particular and consequently to weight loss. Taste alterations may persist for months after therapy, increasing the costs of supplemental nutrition.

In addition to their clinical implications, swallowing disorders and other dysfunctions of the oral anatomy have profound implications for nutritional status and for psychosocial functioning . These dysfunctions occur despite the use of organ-preserving surgical techniques . Difficulty swallowing and the fear of aspiration lead to reduced oral intake and weight loss with their attendant costs . Poor QOL and increased depression and social isolation also have been reported in conjunction with swallowing dysfunction.

Osteonecrosis caused by irradiation of the mandible or maxilla or long-term steroid use has been well described. In the last 5 years, it has also been described after pharmacologic treatment with bisphosphonates (eg, pamidronate or zoledronic acid; see the article by Ruggiero and Woo elsewhere in this issue) . Unlike cases of osteoradionecrosis, which may respond to antimicrobial agents, hyperbaric oxygen, and surgical management , bisphosphonate-associated osteonecrosis may become a chronic source of pain, reduced function, infection, and their corresponding costs . Owing to the syndrome’s recent description, no studies of the costs of managing osteonecrosis of the jaw have been published to date.

Early identification and intervention are essential to minimize the previously mentioned complications; therefore, careful and frequent monitoring is vital. Several tools have been developed to monitor symptoms. Among these are symptom-specific tools such as the Brief Pain Inventory and global symptom tools such as the M. D. Anderson Symptom Inventory . Both assessments can be administered over the telephone by use of an interactive voice response system as well as in person during clinic visits. They are both available in multiple languages. These tools do not replace a clinical examination but facilitate the early identification of problems, particularly among outpatients. Symptom assessment tools have been developed specifically for head and neck cancer patients who undergo radiotherapy .

The psychosocial and economic burden of oral complications of cancer and cancer therapy

Although they are often described in the literature as separate clinical entities, the oral complications of cancer and its therapy are interrelated. For this reason, they share not only clinical characteristics but also clinical, functional, psychosocial, and economic outcomes ( Fig. 2 ).

Although oral complications can be debilitating and costly, they are rarely fatal. Systemic infections are notable exceptions to this rule, as is malnutrition which, through its association with a poor response to therapy, can also affect survival . The focus herein is on the intermediate outcomes of oral complications, that is, weight loss, family and role functioning, QOL and cost, and their interrelationships, rather than on ultimate outcomes such as mortality. The intermediate outcomes are shared to varying degrees by the complications discussed next.

Oral pain in some cases is a primary symptom of oral cavity and oropharyngeal tumors; in other cases it is a complication of therapy (see the articles by Clark, Ram, and Lalla and colleagues elsewhere in this issue). It is among the defining symptoms of oral mucositis but is also a prominent feature of oral cavity infections and osteonecrosis of the jaw . The initial approach to oral pain should involve the prescription of the least potent agent that is effective. Among patients with severe pain, more expensive analgesics may be required . Some patients may even require costly hospitalization and the delivery of opioids by a patient-controlled analgesia pump. Regardless of its cause, oral pain leads to reduced functional status, particularly with respect to eating, swallowing, and communication, with far reaching clinical, psychosocial, and economic implications. The inability to eat or swallow leads to weight loss and the need for dietary supplements, total parenteral nutrition through central venous catheters, or gastrostomy tube insertion for nutrition. Equally important, disturbances in the ability to talk and eat may lead to depression and social isolation at a time when patients most need the support of family and friends.

Oral mucositis is a common and debilitating complication of antineoplastic therapy and a common cause of oral pain . It occurs in virtually all patients who receive radiotherapy for oral cavity and oropharyngeal cancers and in more than 50% of those treated for hypopharyngeal and laryngeal cancer . In the latter population, the incidence of laryngeal mucositis is probably higher, although this has not been systematically studied owing to difficulties of examining these sites. In the head and neck cancer population, mucositis is associated with a high frequency of pain, dysphagia, and weight loss . These outcomes lead to increased requirements for gastrostomy tube insertions, hospitalizations, and an incremental cost of $1700 to $6000 per patient depending on the grade of mucositis . The risks and the severity of the adverse clinical and economic outcomes of radiation are increased by concomitant administration of chemotherapy and by accelerated schedules . For an in-depth review of oral mucositis, the reader is referred to the article by Lalla and colleagues elsewhere in this issue.

Amifostine is a radioprotector used to decrease the side effects of radiation. Its efficacy in reducing mucositis is debated. In a large phase III trial evaluating the efficacy of amifostine in xerostomia reduction for patients receiving radiation to the head and neck, amifostine was not believed to affect the incidence of mucositis, but mucositis was not the primary endpoint of this study . In contrast, in a small randomized clinical trial, the use of amifostine to reduce chemoradiation-induced mucositis and its adverse intermediate outcomes (infection, reduced alimentation, hospitalization) was shown to reduce the cost of supportive care, even after accounting for the acquisition price of the drug . Among patients receiving multicycle chemotherapy for ovarian cancer, amifostine use cost $36,161 per quality adjusted life-year gained . In contrast, a Cochrane review suggested only minimal benefit from use of amifostine .

Among patients who undergo hematopoietic cell transplantation (HCT), the risk of oral mucositis is high depending on the mucotoxicity of the conditioning regimen and whether total body irradiation is prescribed . In the HCT population, mucositis has been associated with poor clinical outcomes and increased costs . The use of palifermin to reduce the incidence of mucositis and its subsequent outcomes has been shown to be cost neutral in an economic study of clinical trial data from patients who received highly mucotoxic conditioning regimens including total body irradiation ; however, its cost-effectiveness has not been studied in other more common HCT settings.

Among patients who receive multicycle chemotherapy without radiation, the risk of oral mucositis varies depending on the regimen received, ranging from little or no risk to more than 50% with some regimens . When mucositis occurs, it is associated with increased risks of weight loss, infections, and hospitalization and an incremental cost of $3000 to $6000 per cycle depending on mucositis grade . Regardless of its cause, the ulceration that characterizes severe oral mucositis provides a portal of entry for microorganisms and the potential for local and systemic infection.

The presence of oral infection is an ominous clinical sign among patients with cancer (see the article by Treister and colleagues elsewhere in this issue) because potentially fatal systemic infections may ensue, particularly during periods of neutropenia . In addition to their clinical implications, these infections reduce QOL and increase cost. Antimicrobial agents are the first expense, and the need for antimicrobials is often accompanied by the need for pain medication. Pain leads to corresponding poor oral intake, weight loss, and the need for nutritional supplements . In cases in which systemic infection develops, intravenous antimicrobial agents with hospitalization may be required. Among HCT recipients, mucositis-associated bacteremias caused by gram-positive bacteria (ie, viridans streptococci , Staphylococcus aureus ) are potentially fatal and contribute to increased length of stay and cost of care . New and reactivated herpetic oral infections are among the most painful of oral infections; they contribute significantly to reduced QOL and to costs of treatment . Among bone marrow transplant recipients, dissemination of new or reactivated infections is avoided by prophylactic decontamination, typically with antiviral agents at a cost of $5 to $8 per patient per day .

Oral pain, infection, and mucositis occur acutely in close temporal proximity to treatment (and to each other). Most instances resolve within 2 to 6 months after treatment is discontinued, although their outcomes, in particular weight loss, often persist more than 6 months after treatment. In contrast, xerostomia, dysgeusia, dysphagia, and osteoradionecrosis, although more severe during treatment, often become chronic problems.

Among the persistent complications of cancer therapy, xerostomia (salivary hypofunction) is a major contributor to reduced function, poor QOL, and high costs . It is a common side effect of radiation for head and neck cancer, and the dose threshold is a subject of controversy . To the extent that intensity modulated radiation therapy (IMRT) spares the salivary glands, the risk and severity of xerostomia hyposalivation appear to be reduced, and recovery over time may occur . Hyposalivation increases swallowing abnormalities and altered taste, resulting in poor nutrition, weight loss, and the costs related to management of poor nutrition . It may also compromise vocal function .

Although it is often considered a complication of head and neck radiation, severe xerostomia was found to be the third most distressing symptom in a study of patients with advanced cancer who had received chemotherapy or analgesics . Treatment for xerostomia and hyposalivation may be as inexpensive as sugarless gum; however, in severe and prolonged cases, pharmacologic sialagogues such as pilocarpine and symptomatic treatment may be necessary at a cost exceeding $100 per month . Professional organizations have recommended that amifostine may be considered for the prevention or reduction of xerostomia and hyposalivation among patients who undergo fractionated head and neck radiotherapy . This radiotherapy protectant has been shown to be effective but is costly.

Alterations of taste that occur after chemotherapy and radiotherapy have important implications for the maintenance of nutritional status. These alterations contribute to poor appetite, lower consumption overall, and lower consumption of protein in particular and consequently to weight loss. Taste alterations may persist for months after therapy, increasing the costs of supplemental nutrition.

In addition to their clinical implications, swallowing disorders and other dysfunctions of the oral anatomy have profound implications for nutritional status and for psychosocial functioning . These dysfunctions occur despite the use of organ-preserving surgical techniques . Difficulty swallowing and the fear of aspiration lead to reduced oral intake and weight loss with their attendant costs . Poor QOL and increased depression and social isolation also have been reported in conjunction with swallowing dysfunction.

Osteonecrosis caused by irradiation of the mandible or maxilla or long-term steroid use has been well described. In the last 5 years, it has also been described after pharmacologic treatment with bisphosphonates (eg, pamidronate or zoledronic acid; see the article by Ruggiero and Woo elsewhere in this issue) . Unlike cases of osteoradionecrosis, which may respond to antimicrobial agents, hyperbaric oxygen, and surgical management , bisphosphonate-associated osteonecrosis may become a chronic source of pain, reduced function, infection, and their corresponding costs . Owing to the syndrome’s recent description, no studies of the costs of managing osteonecrosis of the jaw have been published to date.

Early identification and intervention are essential to minimize the previously mentioned complications; therefore, careful and frequent monitoring is vital. Several tools have been developed to monitor symptoms. Among these are symptom-specific tools such as the Brief Pain Inventory and global symptom tools such as the M. D. Anderson Symptom Inventory . Both assessments can be administered over the telephone by use of an interactive voice response system as well as in person during clinic visits. They are both available in multiple languages. These tools do not replace a clinical examination but facilitate the early identification of problems, particularly among outpatients. Symptom assessment tools have been developed specifically for head and neck cancer patients who undergo radiotherapy .

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses