Chapter 3

Practice of Medicine: Primary Care

The field of medicine is continually expanding as new knowledge and concepts are put into practice. But at the base level of the healthcare delivery system, we begin with primary care: general practice, pediatrics, family practice, and internal medicine. Physicians in these areas are responsible for the total healthcare needs of their patients. They are termed “primary” medical specialists because they are usually the first providers one would consult about a medical problem. This chapter will include two other providers of primary care not discussed in the previous edition of this book: integrative medicine and direct care, sometimes referred to as “concierge care.” In addition, Chapter 4 presents Community Health Centers, also known as “safety-net clinics,” providers of primary care to the underserved and often uninsured. The Affordable Care Act funnels considerable money to federally qualified (community) health centers to care for the large numbers of persons who will now have healthcare coverage and, one hopes, access to care.

If a medical condition requires a specialist, the family practitioner or internist will then refer the patient to a specialist—perhaps a urologist, neurologist, orthopedist, or allergist. There are certain obvious exceptions to this primary-care referral system. People frequently consult allergists, plastic surgeons, dermatologists, obstetricians and gynecologists, or orthopedists on their own if they feel certain they have a problem that falls within that specialist’s domain.

While a primary physician may refer patients to a specialist to consult on a specific problem, he or she will be in contact with the specialist and will retain overall responsibility for the patient’s care. This provides for continuity of care—one physician who records a continuing health history for a patient and who oversees and coordinates total healthcare over a period of years. This is particularly important for patients with long-term disabilities or chronic conditions such as diabetes, heart disease, or hypertension. In managed-care systems, the primary-care referral physician is often called the “gatekeeper,” since access to specialty care is controlled by this individual.

The terms “general practice” and “family practice” are sometimes used interchangeably but they are different although both provide primary care. A general practitioner (G.P.) is a doctor who, having completed medical school and an internship, began his or her medical practice. A G.P. gains a broad general knowledge through experience that enables him or her to treat most medical disorders encountered by his or her patients. Doctors in family practice do a three-year residency that provides training in all major areas of medicine such as surgery, obstetrics and gynecology, pediatrics, internal medicine, geriatrics, and psychiatry. The practice of family medicine is based on four principles of care: continuity, comprehensiveness, family orientation, and commitment to the person.1 Family practice is recognized as a medical specialty by the American Board of Medical Specialties and these physicians are board certified. G.P.s practice primary care but lack board certification in family medicine or internal medicine. For the purpose of space planning, the needs of general practice and family practice physicians are identical.

FAMILY PRACTICE

The individual rooms that comprise this suite, with modifications, form the specialized suites to be discussed in future chapters. Together, these rooms constitute the basic medical suite. Therefore the philosophy behind the design of these individual rooms (waiting room, business office, exam room, consultation room, nurse station, and lab) will be discussed in depth in this chapter.

Functions of a Medical Suite

- Administrative

- Waiting and reception

- Business (appointments, bookkeeping, insurance, clerical)

- Medical records (now electronic EHR)

- Patient care

- Examination

- Treatment/minor surgery

- Consultation

- Collaboration space

- Support services

- Nurse station/laboratory

- X-ray

- Storage

- Staff lounge/break room

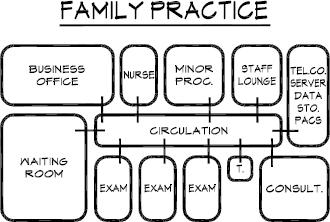

Figure 3-1 shows the relationship of rooms. The patient enters the waiting room, checks in with the receptionist (usually at a transaction counter between the business office and waiting room), and takes a seat in the waiting room. Since most medical offices require advance appointments (as opposed to walk-ins), the staff are able to access the patient’s medical records on the EHR in advance and the patient, upon arrival, may be asked to verify any changes in address or insurance coverage.

Figure 3-1. Schematic diagram of family practice suite.

Later, a nurse or medical assistant calls the patient to the examination area. Usually, the nurse or assistant will then weigh the patient, may request a urine sample (if required), record blood pressure, temperature, and take a short history. The scale is often located at the nurse station but vital signs are taken in the exam room and this is where a brief discussion occurs about the nature of the visit. The patient may be asked about any changes in a chronic condition or about any new medications.

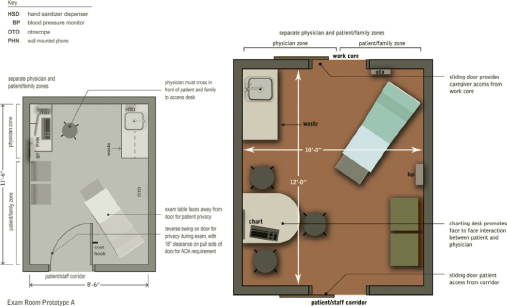

In the exam room, the nurse or medical assistant (M.A.) prepares the patient for the examination and arranges the instruments the physician will need. The doctor enters the room, washes his or her hands, chats with the patient about symptoms, writes or types notes in the patient’s chart (soon all will be EHR), and proceeds to examine the patient, often with a nurse or assistant in attendance. There are individual preferences as to how the physician discusses the diagnosis and treatment plan with the patient and this is also a matter of how the exam room is laid out—whether it has an area for consultation, as in Figures 3-2, 3-3, and 3-4a and b, or whether it is the “traditional” 8 × 12–foot exam room as in Figure 5-3. It is also influenced by the age of the patient and cultural background as to whether it would be psychologically uncomfortable for the patient to sit next to the doctor while gowned. Some physicians ask the patient to dress and they leave the room, returning 10 minutes later to discuss the diagnosis. Alternatively, while the patient is gowned the doctor diagnoses and prescribes right in the exam room. Sometimes the patient is asked to dress behind a cubicle drape while the physician remains in the room and charts the plan of action (see Figure 5-4). Then they sit at a lowered countertop or desk, making eye-to-eye contact, in discussion, sometimes looking at a monitor together. The presence of the computer and monitor in exam rooms has enabled physicians to sit beside patients to review lab tests, X-rays, and educational material. The patient leaves the office, passing an appointment desk or window where future appointments may be booked and where, occasionally, payments may be made. Usually co-pays are collected upon check-in.

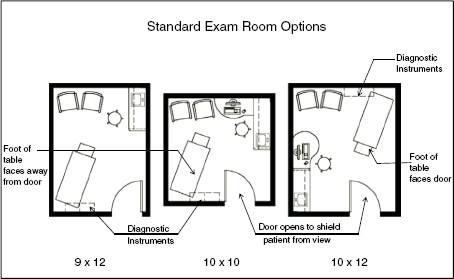

Figure 3-2. Primary care exam room.

Figure 3-3. Standard exam room layout options.

Figure 3-4. Examination room space plan options. (a) Potential features of a 9 × 12 room. (b) A 10 × 12 room allows for a consultation table.

Obvious deviations to the above may occur when, for example, a patient breaks a limb. In this case, the patient may be sent to an X-ray room first, and then proceed to a minor surgery room to have a cast applied without ever entering an exam room. Alternatively, once a break has been established, the patient may be referred to an orthopedist for care.

Some medical practices have fully embraced electronic patient management. Using a secure portal, patients may log in, update their medical histories, find an available slot in the appointment schedule, book it, and also communicate by email with a provider to ask questions. Lab test reports can be viewed through this portal as well as pre-procedure tutorials. This is very efficient and convenient for patients and empowers them. Some physicians have not implemented it because it takes time to respond and they cannot bill for this time. It is hoped that the ACA will bring some changes in this regard. If the only way a patient can get a question answered is to be physically present in an exam room this will continue to clog physicians’ schedules, but one can’t fault them for wanting to be paid for their expertise. When communicating informally with a patient in an email, there are likely other issues of concern to physicians such as documentation of the correspondence for legal purposes and recordkeeping, but it could all be archived within the patient’s portal. The system is broken and needs to be fixed. Everyone knows that; five years from now all this will likely have been sorted out.

Flow

The efficiency of the medical practice will be largely influenced by the flow of patients, staff, and—to a lesser degree—supplies, through the suite. The layout of rooms must be based on a thorough understanding of how staff interface with patients and, most important, separation of incoming and outgoing traffic (see Figures 7-1 and 7-2). This is rarely possible in a small office for one or two practitioners but is increasingly important as the size of the office grows.

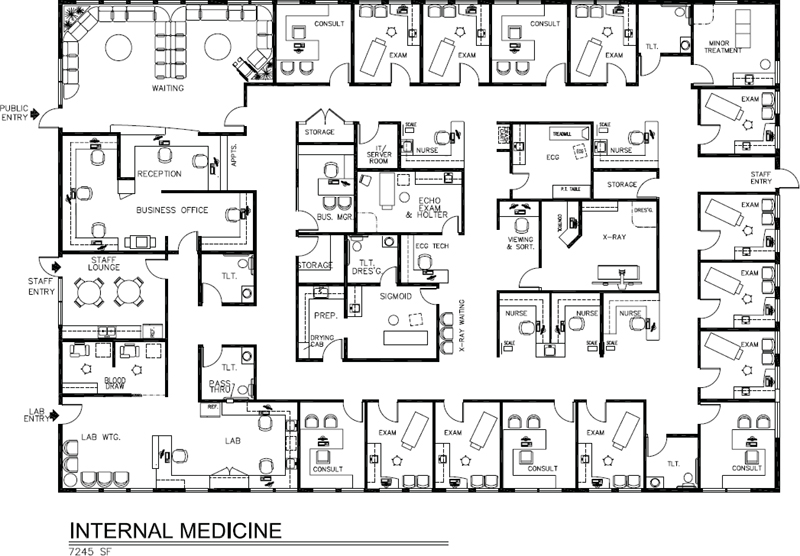

In Figure 3-5, exam rooms and consultation rooms are arranged in clusters, enabling five physicians to practice simultaneously with two exam rooms each in addition to a procedure room, ECG, and sigmoid. There is the option of a fifth physician at any time having a day off, which would then provide 2.5 exams rooms per each of four physicians. Patients, after checking in with the receptionist, proceed to one of five nurse stations to be weighed. If a urine specimen is required, the patient would be directed to the specimen toilet in the lab. For those arriving for lab work only, or for those who know they need lab work after having visited the physician and who are now on their way out of the suite, the lab is conveniently located with a direct entry/exit. The exit/checkout path of travel is more or less separate from the ingress. Circulation for staff is direct, enabling them to quickly access all parts of the suite without having to navigate a maze.

Figure 3-5. Space plan, internal medicine suite, 7,245 square feet.

Electronic Communication Systems

Flow can be enhanced and managed by custom light-signaling communication systems that consist of a panel of colored signal lights mounted on the wall of exam and procedure rooms, nurse stations, and the reception area. By glancing at a panel or pressing a button, physicians and staff can silently be notified of messages and emergencies, let others in the office know where they are located, and tell nurses and technicians where they are needed. The sequence memory program advances automatically, telling the doctor which patient is next. Monitor panels at nurse stations indicate at a glance the status of exam rooms, while another panel at the reception desk notifies clinical staff when patients have arrived and which provider they’re scheduled to see. Expeditor Systems of Alpharetta, Georgia, is a leading vendor of these systems.

An add-on to the Expeditor communication system, called Practice Profiler®, provides room utilization analysis and documentation of the entire patient encounter. It measures the time a patient spends waiting in the exam room before the doctor arrives, the amount of time the doctor spends with the patient, and a monthly report on physician and staff productivity is emailed to subscribers. This type of data can help physicians become more efficient in the eternal quest to see more patients each day without sacrificing quality.

Another vendor, Kelkom, offers a similar type of signal communication and workflow management system that delivers information via a hardwired panel, a wireless tablet, or a virtual panel on a PC screen that disappears when in work mode with the patient (see Figure 10-57). Comlite, a third vendor, offers another customized system that is software-based which tells physicians what patient is in which room, who is next, and summons staff.

Physician Extenders

In recent years physicians (especially those in group practices) have increasingly added physician extenders (PEs) to their patient care management teams. Also referred to as “midlevel providers,” these generic terms usually refer to physician assistants (PAs), medical assistants (MAs), and advanced practice registered nurses (APRNs). According to the American Association of Colleges of Nursing, APRNs are advanced registered nurses, typically with master’s degrees, who fall into four categories:

- Nurse practitioners, who provide primary-care diagnosis and treatment, immunizations, physical exams, and management of common chronic problems

- Certified nurse midwives, who provide prenatal, postpartum, and gynecological care to healthy women, and deliver babies in a variety of settings

- Clinical nurse specialists, who are trained in a range of specialized areas such as oncology, cardiac care, and pediatrics

- Certified registered nurse anesthetists, who, according to the American Association of Colleges of Nursing, administer more than 65 percent of all anesthetics given to patients

Statistics for nurse practitioners, the largest group of APRNs, indicate that 22 states allow nurse practitioners (NPs) to practice independently without physician supervision, 24 states require a formal relationship (documented in writing) between an NP and a physician, and 4 states require the relationship but without the formal documentation. Only 13 states allow NPs to prescribe medications without the supervision of a physician.

Clearly, the use of physician extenders dovetails with the economics of our current healthcare system and the exigencies of the Affordable Care Act (ACA). Studies by the Medical Group Management Association (MGMA) and the American Medical Association (AMA) Center for Health Policy Research indicate that PEs can increase a physician’s productivity and income and that patients are generally pleased with the quality of care delivered. Under Medicare regulations, services provided by a physician assistant in most physicians’ offices are reimbursed the same as if provided by a physician.

If the medical practice includes physician extenders, they will require shared or private offices, based on the tasks they perform and their roles in the practice (Figure 3-6). Thus, a four-physician office with two PAs and one NP is a seven-provider office for the purpose of determining the number of exam and treatment rooms.

Figure 3-6. Medical assistant workstation.

MANUAL VERSUS DIGITAL INSTRUMENTATION FOR DIAGNOSIS

The contrast between the use of manual diagnostic instruments and those with digital output is dramatic. The ubiquitous Welch Allyn diagnostic instrument panel mounted on the wall in almost every exam room relies on the practitioner’s senses—hand to eye and eye to brain—versus the same instrument panel with wireless automated vital signs capture that uploads to an EHR. The Welch Allyn Connex® integrated wall system is fully electronic with pulse oximetry, pulse rate, blood pressure, and thermometer (Figure 3-7a). The otoscope and ophthalmoscope, if desired, can upload video images to a PC for transmission to another physician or upload them to the patient’s EHR, which can also be useful if documentation is later needed for insurance verification of a claim. The AMD ophthalmoscope in Figure 3-7b is used widely by primary care and pediatric physicians for video examination of the retina. The avoidance of duplicate data entry and the efficiency afforded by electronic diagnostic devices will likely, over time, make it easy to recover the initial cost in a primary care setting where the emphasis is on seeing more patients in less time and providing a satisfying experience for them.

Figure 3-7a. Welch Allyn Connex® integrated wall system.

Figure 3-7b. Mobile ophthalmoscope attached to smartphone.

INTERCONNECTIVITY AND BIG DATA

Interconnectivity is the name of the game in the new healthcare system. This is IT on steroids—what’s called “Big Data.” It’s one thing to have all your systems sharing data and “talking” to each other but entirely another to be able to analyze all the data meaningfully to be able to demonstrate value-based care. Currently, it is still a problem for private practice physicians to gain access to a patient’s medical records for emergency department visits, for example, and vice versa. It is totally understandable, however, since although a private practice physician may have privileges at that hospital, he or she is not a salaried provider and many potential legal issues arise with providing access to a patient’s confidential medical records. Nevertheless, it is frustrating for patients who visit private practice physicians in medical office buildings at different hospital campus sites (within the same system) to not have access to medical records. Patients who enroll in a hospital’s health plan and receive treatment from providers within that system, at whatever sites they choose to access, can reasonably expect total interconnectivity and sharing of data, whether they are inpatients or outpatients. If a patient selects, for example, Mayo Clinic, Cleveland Clinic, or Scripps Clinic, the entire network of clinic sites and hospitals will have access to the patient’s medical chart, which offers the patient a great advantage in collaborative and coordinated care.

EXAMINATION ROOM DESIGN CHANGES

It is clear the “future” has arrived. One can see how the practice of medicine is being transformed by digital technology. But, psychologically, are physicians ready and willing to discharge their responsibilities and sensory contact with patients to an electronic device? Physicians who have been in practice for many years pride themselves on being able to tell a great deal by looking at a patient’s skin tone, or examining their tongues, or picking up some elusive quality during the process of monitoring vital signs. After all, medicine is a science and an art. And with interest in integrative medicine (integration of allopathic or Western medicine and complementary therapies) steadily growing, it won’t be easy to forge a marriage between digital technology and New Age “energy” medicine. James Bond meets Andrew Weil.

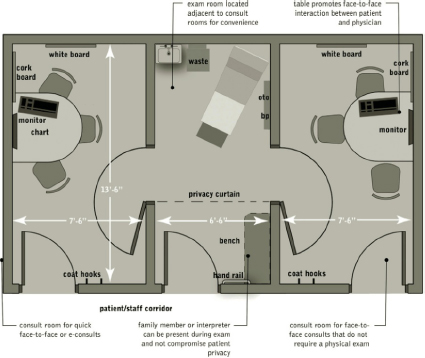

[From a 2014 perspective, this doesn’t have to be a zero sum game. With a properly designed exam room, it can be both high-tech and high-touch with physicians relying on EHR to more quickly access notes in order to spend more quality time face to face with patients. New exam room designs integrate computers and monitors in numerous layouts offering individual practitioners many options according to personal preference (see Figures 1-1, 3-2, 3-4b, 3-8, 3-9, and Color Plate 6, Figure 3-123). Likewise, exam room size is growing. The “new” exam room is covered in detail later in this chapter. The room in Figure 3-4b can be used as an exam room or a talking room.]

Figure 3-8. Talking room suite concept.

Figure 3-9. Examination room consultation station.

PLACEBO EFFECT

In integrative medicine, rapport between the physician and patient is key to a successful outcome. According to Herbert Benson, M.D., author of Timeless Healing: The Power and Biology of Belief, the placebo effect (belief that causes self-healing) is greatly enhanced when the patient believes that the physician is capable of healing him, when the physician believes in the efficacy of the treatment, and when, together, there is a belief in the relationship. In the end, digital technology need not preclude developing a warm and caring relationship with patients. By automating the more routine aspects of a patient visit, the physician may have more time to spend as diagnostician and teacher.

One cannot fail to observe that, despite seismic pressures on physicians and the healthcare system in general, the clinical office practice has changed little in decades—that is, until now. The description below, by Charles Kilo, M.D., of IHI, is dated 1998 and it still holds true today, in 2013, except for a handful of pilot projects such as the innovative Ambulatory Practice of the Future discussed below. The Affordable Care Act (ACA) will spawn more such experiments as providers try to truly redesign the way they deliver care to be more efficient and effective.

Few can disagree with IHI’s premise:

The clinical office lies at the heart of health care. For most patients most of the time, it is the portal of entry, the communications hub, the primary locus of care, and, in these days of integrated care, the coordinating center. For most doctors, too, it is home base; they speak of the hospital, but my office.

The average clinical office practice of today bears remarkable similarity in form, process, design, and activity to the offices of a decade, two decades, even a half-century ago. In the typical office setting, patients still phone in for appointments, register upon arrival, wait in waiting rooms, disrobe in examination rooms, listen in consulting rooms, and wave good-bye to the receptionist in a sequence of actions that would look nearly identical if we could compare, say, 1950 to 1998. A few differences would be noticeable, of course—the desktop computer instead of the typewriter, the otoscope now fiberoptic, the furniture modular, the increased ability to provide certain treatments such as antibiotics and chemotherapeutics, and the credit card taken and checked automatically. But, the core sequence, the systems that support the work and, more importantly, the assumptions about what work is to be done, would all be almost identical—1950 equals 1998.3

THE TRIPLE AIM

The Triple Aim is a framework developed by the Institute for Healthcare Improvement that describes an optimizing health system performance. It underscores three critical objectives of the ACA:

- Improve the health of the population

- Enhance the patient experience of care (quality, access, reliability)

- Reduce the per capita cost of care

Patient-Centered Medical Home

There is a fundamental restructuring of primary care occurring in the United States and it is largely focused on the Patient-Centered Medical Home (PCMH), which is a foundational piece of the Accountable Care Organization (ACO). The many patients who will gain healthcare coverage as a result of the ACA may not actually have access unless a fundamental shift in care management occurs. Valuable lessons can be learned from the approach to holistic care at two ends of the spectrum—safety-net community health centers (refer to Chapter 4), and from physicians who practice membership-based direct care, sometimes referred to as “concierge care.” Both achieve a high level of continuity of care, create a medical home for patients, and offer prompt access and coordination of care for patients who have chronic or complex medical conditions. The ACA will ramp up the need for primary care and the deployment of many more community health center and ambulatory care facilities, but the physical design and clinical workflow will be distinctly different from existing models. Clearly, the focus is on wellness, management of chronic conditions, team-based care delivery, an optimized and personalized patient experience, and measurement of performance in health outcomes. In fact, a value-based payment model is on the horizon. Here comes the need for “Big Data” analytics. Experiments are going on around the nation as physicians try to respond to the new normal of reduced reimbursement, prevention, and the tsunami of newly insured patients heading their way. It’s an exciting time to be working in healthcare as it is reshaped and reformed in ways that will hopefully achieve the IHI’s Triple Aim.

An important building block of primary care reform is the creation of Patient-Centered Medical Homes. The concept actually parallels in a more formal way the characteristics of safety-net health centers in terms of delivery of care. To be designated a PCMH, “primary care practices are expected to provide comprehensive primary care including care management, care coordination, enhanced access, patient engagement, and proactive patient planning and are expected to be NCQA (National Committee for Quality Assurance) Level 3 or an equivalent (i.e., complete medical homes) and meaningful use certified.” (www.transformed.com/ceoreports/comprehensive_primary_care_initiative.cfm; retrieved 15 March, 2013).

Transforming Care

Think about the radical change here. Typically one consults a primary care physician for episodic care and the diagnosis and advice are generally limited to that one specific visit. Whereas, becoming a PCMH requires a physician to proactively follow up with each patient, creating a care plan whether it is prevention and wellness for a healthy person or a plan that extends community-wide for a patient with chronic conditions and comorbidities to reach out to a variety of providers from nutritionists to physical therapists and home health agencies. Coordinating all of this and eventually measuring if one is providing value according to state and national metrics is a daunting task, especially with continually lower reimbursement. The proposition is: If patients receive health care, not sickness care, they will ultimately need less of it, some may avoid chronic debilitating illnesses, and emergency room visits will go down as will hospital admissions. But that is based on patients being compliant and some inroads being made in controlling the nation’s obesity problem. A lot of “ifs.” This is why “improving the health of the population” is one of the Triple Aims. Healthcare is moving from the individual to the community and one expression of this is the Patient-Centered Medical Neighborhood.4

The American Academy of Family Physicians established TransforMED in 2005 to assist physicians in transforming their practices to a new model of care. Their website (transformed.com) offers many interesting resources and articles on PCMH and Patient-Centered Medical Neighborhoods (PCMN). In 2007, leading primary care associations endorsed the Joint Principles of the Patient-Centered Medical Home as a goal for the organization and for delivery of care throughout the healthcare system. It requires a high level of information technology, provider payment reform that rewards outcomes, and team-based education and training of the health professions workforce (www.pcpcc.net/what-we-do). In 2008 the Commonwealth Fund launched the five-year Safety-Net Medical Home Initiative to help 65 community health centers transform into Patient-Centered Medical Homes. In 2010 the ACA included substantial support for medical home initiatives, including the CMS Advanced Primary Care Practice Demonstration bringing together, for the first time, public and private health plans to examine the effectiveness of medical homes. As of January 2012, 41 states had adopted medical home programs; however, they structure their definitions and priorities differently. In some states, payments to providers may vary depending on the number of chronic conditions a patient has and if there is a language barrier or mental illness. In other states, payments are based on a maximum per member per month that varies with the payer type (Medicare Advantage Plans, Medicaid, commercial payers) and may vary based on medical home effectiveness. A state may pay primary care providers for remote consultations with hospital-based specialists to improve care for complex patients or they may receive funding for establishing a registry for tracking important patient data to develop a system for sharing clinical information perhaps with a key hospital.

PCMH Accreditation Agencies

There are various accreditation agencies for PCMH each with a set of standards and specific criteria. The Joint Commission, in 2011, launched the Primary Care Medical Home Certification option for its accredited ambulatory care organizations. In addition, the Accreditation Association for Ambulatory Health Care (AAAHC) offers accreditation for medical homes. There is the National Center for Medical Home Implementation Accreditation and the National Committee for Quality Assurance (NCQA) PCMH Recognition designation that has three levels of achievement.

Financial Benefits of Medical Homes

Leading insurance payers, such as WellPoint and United Healthcare, expect that PCMHs have the potential to save twice as much as they cost with estimates of 70 percent reduction in ED visits and 40 percent fewer hospital readmissions. (See Tables 1 and 2 (www.pcpcc.net/guide/benefits-implementing-pcmh) for outcome measures for 7 of the 41 states engaged in PCMH demonstration projects.) In addition, the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (ahrq.gov/research/primarix.htm), awarded, in 2010, 14 two-year “transforming primary care” grants to selected organizations to study the transformation of primary care practices to PCMHs. A description of each project’s diverse objectives can be found on the AHRQ website (ahrq.gov/research/transpcaw.htm).

Table 3-1. Analysis of Program Family Practice

| No. of Physicians: | 1 | 2 | 3 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Consultation Room/ Private Office |

12 × 12 = 144 | 2 @ | 12 × 12 = 288 | 3 @ | 12 × 12 = 432 | |

| Exam Rooms | 3 @ | 10 × 12 = 360 | 6 @ | 10 × 12 = 720 | 9 @ | 10 × 12 = 1080 |

| Waiting Room | 14 × 18 = 252 | 16 × 20 = 320 | 18 × 20 = 360 | |||

| Business Officea | 12 × 18 = 216 | 16 × 18 = 288 | 18 × 30 = 540 | |||

| Office Manager | 10 × 12 = 120 | 10 × 12 = 120 | ||||

| Nurse Stations | 10 × 12 = 120 | 2 @ | 10 × 10 = 200 | 3 @ | 10 × 10 = 300 | |

| M.A. Workstation | 6 × 10 = 60 | 6 × 10 = 60 | 6 × 12 = 72 | |||

| Toilets | 2 @ | 8 × 8 = 128 | 2 @ | 8 × 8 = 128 | 3 @ | 8 × 8 = 192 |

| Storage | 6 × 8 = 48 | 8 × 8 = 64 | 10 × 10=100 | |||

| Cast Room | Use Minor Surgery | Use Minor Surgery | Use Minor Surgery | |||

| Staff Lounge | 8 × 10 = 80 | 10 × 12 = 120 | 12 × 12 = 144 | |||

| Minor Surgery | 12 × 12 = 144 | 12 × 12 = 144 | 12 × 14 = 168 | |||

| Radiologyb | — | 16 × 20 = 320 | 16 × 20 = 320 | |||

| Laboratory | 8 × 8 = 64 | 8 × 10 = 80 | 16 × 16 = 256c | |||

| Tel. Equip/Server Closet | 4 × 5 = 20 | 4 × 5 = 20 | 4 × 5 = 20 | |||

| Biohazard Storage | 4 × 4 = 16 | 4 × 4 = 16 | 4 × 4 = 16 | |||

| Subtotal | 1652 ft.2 | 2888 ft.2 | 4120 ft.2 | |||

| 20% Circulation | 330 | 577 | 824 | |||

| Total | 1982 ft.2 | 3465 ft.2 | 4944 ft.2 | |||

| a Includes reception, appointments, bookkeeping, and insurance/collections. | ||||||

| b Includes control and dressing area. | ||||||

| c Includes lab, sub-wait, and blood draw. | ||||||

| Note: Consultation rooms (private offices) may be smaller (10 × 12) or shared (two physicians in a 12 × 12 room). | ||||||

Table 3-2. Analysis of Program Internal Medicine

| No. of Physicians: | 2 | 3 | 4 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Consultation Rm./ Private Office | 2 @ | 12 × 12 = 288 | 3 @ | 12 × 12 = 432 | 4 @ | 12 × 12 = 576 |

| Exam Rooms/Talking Rooms | 6 @ | 10 × 12 = 720 | 8 @ | 10 × 12 = 960 | 10 @ | 10 × 12 = 1,200 |

| Waiting Room | 14 × 18 = 252 | 20 × 20 = 400 | 20 × 24 = 480 | |||

| Business Officea | 16 × 20 = 320 | 20 × 20 = 400 | 24 × 26 = 624 | |||

| Office Manager | 10 × 12 = 120 | 10 × 12 = 120 | 10 × 12 = 120 | |||

| Nurse Stations | 2 @ | 10 × 10 = 200 | 3 @ | 10 × 10 = 300 | 4 @ | 10 × 10 = 400 |

| M.A. Workstation | 6 × 10 = 60 | 6 × 10 = 60 | 6 × 12 = 72 | |||

| Storage | 8 × 8 = 64 | 8 × 10 = 80 | 8 ×10 = 80 | |||

| Toilets | 2 @ | 8 × 8 = 128 | 3 @ | 8 × 8 = 192 | 4 @ | 8 × 8 = 256 |

| Flex Sig. Roomb | 300 SF | 300 SF | 300 SF | |||

| Staff Break Room | 10 × 12 = 120 | 12 × 12 = 144 | 12 × 16 = 192 | |||

| Laboratory | 12 × 20 = 240 | 300 SF | 400 SF | |||

| Toilet | 8 × 8 = 64 | 8 × 8 = 64 | 8 × 8 = 64 | |||

| ECG/Treadmill | 12 × 12 = 144 | 12 × 12 = 144 | 12 × 12 = 144 | |||

| ECG Tech Workstation | 6 × 6 = 36 | 6 × 6 = 36 | 6 × 6 = 36 | |||

| Pulmonary Function Testing | — | (Optional) | 14 × 20 = 280 | |||

| Echo Exam & Holter | 10 × 14 = 140 | 10 × 14 = 140 | 10 × 14 = 140 | |||

| Radiologyc | — | 16 × 20 = 320 | 16 × 20 = 320 | |||

| Tech workstation | — | 5 × 6 = 30 | 5 × 6 = 30 | |||

| Tel. Equip./ Server Closet | 4 × 5 = 20 | 4 × 5 = 20 | 4 × 5 = 20 | |||

| Biohazard Storage | 4 × 4 = 16 | 4 × 4 = 16 | 4 × 4 = 16 | |||

| Subtotal | 3,232 SF | 4,458 SF | 5,750 SF | |||

| 20% Circulation | 646 | 891 | 1,150 | |||

| Total | 3,878 SF | 5,349 SF | 6,900 SF | |||

| a Includes reception, appointments, bookkeeping, and insurance/collection. | ||||||

| b Includes scope workroom and toilet; used for various types of special procedures. | ||||||

| c Includes control and radiography room. | ||||||

| Note: Consultation rooms (private offices) may be smaller (10 × 12) or shared (two physicians in a 12 × 12 room. Exam rooms and talking rooms are the same size but furnished differently. | ||||||

Geisinger Clinic has been celebrated by the Obama Administration and the American Hospital Association as one of the nation’s most effective providers, achieving quality outcomes at moderate cost. Through its ProvenCare program (a version of the medical home model), the health plan integrates care managers into the clinical team to proactively keep in touch with patients to coach them. “Every time the system ‘touches’ the patient, it is reported to the case manager, who calls the patient and coordinates appropriate care—for example, reminding the individual to pick up a prescription.5 Accordingly to Dr. Alfred Casale, this has resulted in a 30 to 50 percent reduction in hospital readmissions and other benefits.

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses