Temporomandibular joint (TMJ) and dentofacial deformities commonly coexist. The TMJ disorders may be the causative factor of the jaw deformity or may have developed as a result of the jaw deformity, or the 2 entities may occur independently of each other. The TMJs form the foundation for jaw position, function, occlusion, facial balance, and comfort. If the TMJs are not stable and healthy (nonpathologic), patients requiring orthognathic surgery may have unsatisfactory outcomes relative to function, aesthetics, occlusal and skeletal stability, and pain. The most common TMJ disorders that can adversely affect orthognathic treatment outcomes include (1) articular disc dislocation, (2) adolescent internal condylar resorption (AICR), (3) reactive arthritis, (4) condylar hyperplasia, (5) ankylosis, (6) congenital deformation or absence of the TMJ, (7) connective tissue and autoimmune diseases, and (8) other end-stage TMJ disorders. These TMJ conditions are often associated with dentofacial deformities, malocclusion, TMJ pain, headaches, myofascial pain, TMJ and jaw functional impairment, ear symptoms, and sleep apnea. Patients with these conditions may benefit from corrective surgical intervention, including TMJ and orthognathic surgery. The difficulty for many clinicians is in identifying the presence of a TMJ condition, diagnosing the specific TMJ disorder, and selecting the proper treatment of that condition.

Approximately 25% of patients with TMJ disorders/pathology are asymptomatic. These asymptomatic patients can be the most troublesome because the TMJ disorder may not be recognized and, thus, not treated, which results in a poor treatment outcome with potential redevelopment of the skeletal and occlusal deformity by condylar resorption or overdevelopment, as well as initiation of pain, headaches, and other TMJ symptoms.

Our research studies and those of others have clearly shown the adverse affects of performing only orthognathic surgery in the presence of displaced TMJ articular discs. With displaced discs and maxillomandibular advancement, an average anteroposterior mandibular relapse of 30% can be expected as well as an 84% chance of developing TMJ and facial pain. Proper surgical intervention for the specific TMJ disorders in orthognathic surgery patients provides highly predictable and stable results.

Patient evaluation

We have previously published detailed information on patient evaluation for orthognathic surgery, including clinical, radiographic, and dental model analyses. When the TMJs are also involved, additional evaluations are warranted to determine the cause, diagnoses, and treatment approach to provide optimal outcomes. It is important to know the patient’s concerns and symptoms as well as treatment expectations. Subjective assessments are recorded relative to headaches, TMJ pain, myofascial pain, jaw function, diet, and disability.

History

The history includes when the patient first had any form of TMJ-related symptoms or changes in the jaw and occlusal relationship, cause, the progression of the condition, and any additional affecting factors contributing to the present circumstance. Are these symptoms static or have they become progressively worse? What previous treatments have been provided? Has the patient had previous orthognathic or TMJ surgery? Does the patient have any habitual patterns such as tongue thrust, clenching and bruxism, or thumb sucking? Are there progressive changes in the occlusion and jaw relationship? Are there other symptomatic joints in the body or major disease processes, such as connective tissue or autoimmune diseases, GI problems, recurrent urinary tract infections, diabetes, cardiac conditions, vascular compromises, airway or sleep apnea issues, smoking, alcohol or drug abuse, or female hormone imbalances? These factors may affect TMJ treatment decisions.

Clinical Examination

Orienting the head so that both the clinical Frankfort horizontal (a line from the tragus of the ear through the bony infraorbital rim area) and the pupillary and ear planes are parallel to the floor positions the head so that facial balance and the skeletal and occlusal relationships in centric relation can be assessed more easily. The patient should be evaluated for skeletal and occlusal class I, II, or III; transverse cant in the occlusal plane; high, normal, or low occlusal plane angle facial morphologic type; facial asymmetry; and dental disease.

Physical examination of the head, neck, and shoulders is performed, including palpation, to determine the presence of muscle pain and functional limitations. The TMJs are examined for incisal opening and excursion movements, pain, noises, dysfunction, and associated facial or functional asymmetries. Airway problems are common in patients with TMJ disorders; thus, airway assessment of the oral cavity, oropharyngeal area, and nasal airway is important for comprehensive treatment. Some patients may need additional evaluations, such as rheumatology, internal medicine, neurology, cardiology, sleep apnea specialists, radiology, dental specialists, or laboratory tests.

Dental Model Analyses

Dental model analysis determines the occlusal relationship and provides information for the orthodontic, surgical, and restorative dentistry protocols necessary to provide a good occlusal relationship as the end product of treatment.

Imaging

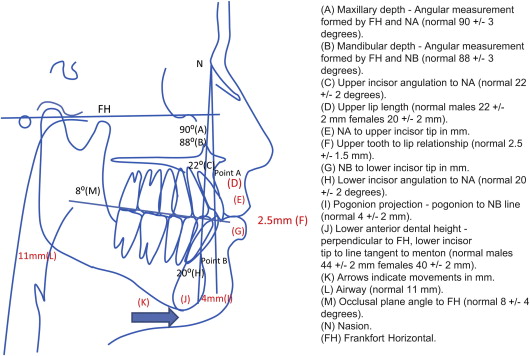

Radiographic evaluation is helpful in the diagnostic process, and cone beam technology makes low-cost, low-radiation computed tomography (CT) scans accessible. One of the best diagnostic tools for TMJ disorders is magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) because it allows evaluation of TMJ disc position, morphology, mobility, extent of joint degenerative changes, inflammation, and the presence of connective tissue/autoimmune diseases. It can help in the diagnosis of TMJ disorders in the silent joint in which disc displacement and degenerative changes can be present but may not make noise or be uncomfortable or painful, but may contribute to poor outcomes if only orthognathic surgery is performed. CT scans, bone scans, three-dimensional (3D) imaging, and 3D modeling may be beneficial for some patients. Cephalometric analysis is an important assessment for diagnosis and treatment planning ( Fig. 1 ).

Comprehensive Diagnostic List and Treatment Plan

Following completion of all necessary and required evaluations, a comprehensive diagnostic list can be compiled. A definitive treatment plan can then be established to address these issues and other treatment options that may be available to allow the patient to make an informed decision as to the preferred treatment.

Gender and Age of Onset

A review of 1369 consecutive patients with TMJ disorders referred to the senior author’s (LMW) practice revealed an age range of 8 to 76 years, with 78% of the patients female and 22% male. Sixty-nine percent of the patients reported the onset of their TMJ problems during the teenage years. Therefore, TMJ disorders predominantly develop in the teenage girls.

Surgical Sequencing

TMJ and orthognathic surgery can be predictably done at the same operation. Surgical sequencing includes (1) TMJ surgery; (2) mandibular ramus sagittal split osteotomies with rigid fixation; (3) maxillary osteotomies and mobilization; (4) turbinectomies and/or septoplasty, if indicated; (5) rigid fixation and bone grafting of the maxilla; and (6) adjunctive procedures, such as genioplasty, rhinoplasty, uvulopalatopharyngoplasty, or facial augmentation.

The TMJ surgery must be done first because some TMJ procedures affect the position of the mandible (ie, disc repositioning, high or low condylectomy). Mandibular sagittal split osteotomies with rigid fixation are done next so the mandible can be placed in the predetermined position regardless of the amount of displacement caused by the TMJ surgery. Also, many patients with TMJ disorders require counterclockwise rotation of the maxillomandibular complex to get the best functional and aesthetic outcomes. In this situation, it is easier to do the mandibular osteotomies before the maxillary osteotomies. If the surgeon prefers to do the TMJ surgery at a separate operation from the orthognathic surgery, then the TMJ surgery should be done first.

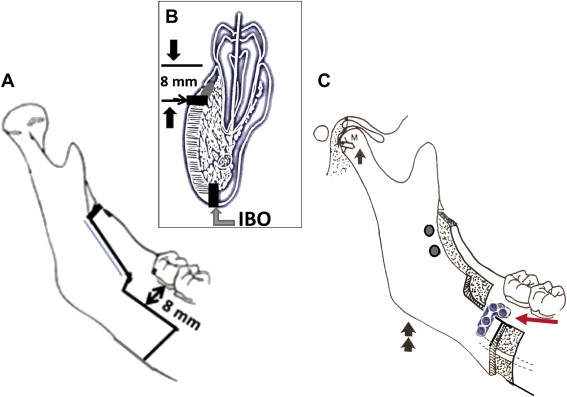

The Wolford modification of the sagittal split osteotomy provides an easy method to position the condyle in the fossa following TMJ surgery ( Fig. 2 ). The primary change is that a horizontal bone cut is made perpendicular to the buccal cortex (8 mm below the gingivocervical margin of the teeth) from just distal to the second molar forward 8 mm further than the amount of mandibular advancement required; as a result, there is a bony interface between the proximal and distal segments to control the position of the proximal segment and accommodate a bone plate and screws. An inferior border osteotomy is performed with a special inferior border saw and segments are separated. The mandible is repositioned with an intermediate splint and maxillomandibular fixation. The proximal segment is positioned beneath the bony ledge of the distal segment and gently pushed posteriorly at its anterior edge; gentle finger pressure is applied externally at the angle of the mandible seating the condyle into the fossa. Rigid fixation is applied, including the specially designed sagittal split bone plate and 1 to 2 screws in the anterosuperior ramus, followed by maxillary osteotomies and ancillary procedures to complete surgery.

TMJ and Facial Asymmetry

TMJ disorders are common causative factors for facial asymmetry and can produce a progressive worsening of the facial deformity and malocclusion. Unilateral condylar underdevelopment or resorption can cause the mandible and face to be smaller on one side and the jaws to shift toward the involved side. A unilateral condylar overdevelopment can also cause facial asymmetry. In this latter patient type, the normal TMJ may also develop disorders (eg, articular disc dislocation or arthritis) from the increased functional loading on that joint created by the overdevelopment of the opposite side. Performing orthognathic surgery only in facial asymmetry cases and ignoring the TMJs during treatment or failure to render proper TMJ management could result in the redevelopment of dentofacial asymmetry and malocclusion with worsening TMJ-associated symptoms, including jaw dysfunction and pain.

Number and Type of Previous Surgeries

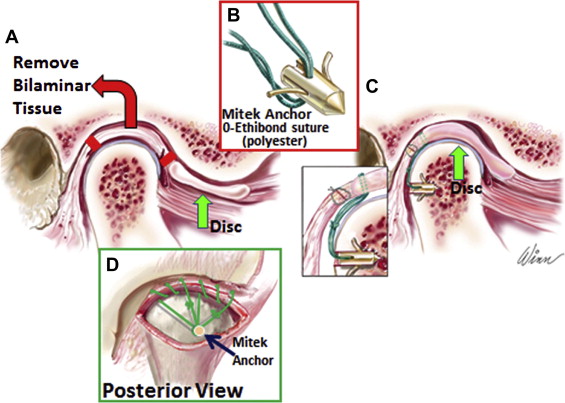

Patients with TMJ articular disc dislocation, 0 to 1 previous TMJ surgeries, and no polyarticular conditions, may benefit from articular disc repositioning and ligament repair with Mitek anchors (Mitek Products Inc., Westwood, MA) to achieve a stable treatment outcome ( Fig. 3 ). The success rate is highest when discs are repositioned within 4 years of initial disc displacement.

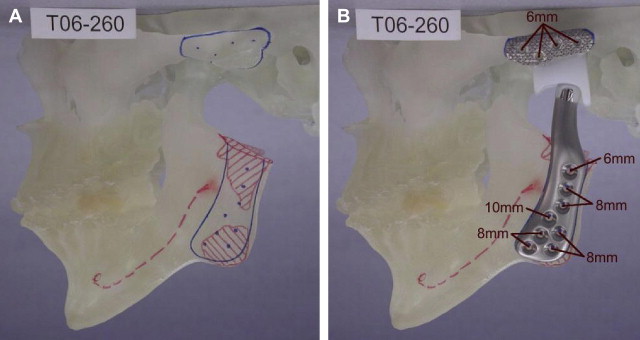

Patients with 2 or more previous TMJ surgeries have a high failure rate with disc repositioning or other autogenous tissue reconstruction. A TMJ total joint prosthesis, such as the TMJ Concepts Inc. system (Ventura, CA), have a much higher rate of success ( Fig. 4 ). Patients with TMJ involvement of connective tissue and autoimmune diseases may benefit from total joint prosthesis reconstruction because the disease processes will likely attack any autogenous tissues placed in the joint area, but will not affect the total joint prostheses. Other end-stage TMJ conditions, such as severe reactive arthritis or osteoarthritis, ankylosis, severe damage from trauma, failed TMJ alloplastic implants, or polyarticular conditions, will get the most predictable results with total joint prostheses and fat grafts packed around the articulating components of the prostheses.

Age for Surgical Intervention

Predictability of results and limiting correction of the jaw and TMJ-related deformities to 1 major operation can best be achieved by waiting until growth is nearly complete. Although there are individual variations, girls usually have most of their facial growth (98%) complete by the age of 15 years and boys by the age of 17 to 18 years. Performing surgery at earlier ages may result in the need for additional surgery at a later time to correct a resultant deformity and malocclusion that may develop during the completion of growth. There are definite indications for early surgery, such as progressive TMJ deterioration, ankylosis, growth center transplants (ie, rib or sternoclavicular grafts), masticatory dysfunction, tumor removal, pain, and sleep apnea. We have previously published studies on maxillary and mandibular surgery and their effects on growth with guidelines for age when considering surgical intervention.

Nonsurgical and Closed Treatment Considerations

Nonsurgical TMJ treatments (eg, splints, physical therapy, chiropractic treatment, orthodontics, biofeedback, acupuncture, and medications) may help the TMJ symptoms but do not stabilize and eliminate TMJ disorders (eg, disc dislocation, arthritis, condylar resorption, or condylar hyperplasia) to withstand the increased TMJ loading that usually accompanies orthognathic surgery. Arthrocentesis and arthroscopy are contraindicated in patients with TMJ disorders requiring orthognathic surgery because these techniques do not reposition and stabilize the articular disc in a normal position, but may convert a reducing disc into a nonreducing disc that will yield a more rapid deformation and degeneration process of the disc, subsequently rendering it nonsalvageable.

Condylar overdevelopment conditions

Condylar Hyperplasia Type 1

Patients with condylar hyperplasia (CH) type 1 may have a class I occlusion at the beginning of puberty and develop into a class III, or begin as a class III but develop a worse class III relationship with accelerated mandibular growth that can continue into the mid-20s, although it is eventually self-limiting. Bilateral active CH type 1 causes progressive worsening prognathism and occlusion but usually asymptomatic TMJs. Unilateral or bilateral CH type 1 with asymmetric growth can cause progressive deviated prognathism, facial asymmetry, disc dislocations, TMJ pain, headaches, and masticatory dysfunction ( Figs. 5 A–D, 6 A). Not all prognathic mandibles are caused by CH; only those showing accelerated, excessive mandibular growth continuing beyond the normal growth years. MRI may show thin discs that sometimes are difficult to identify; they tend to have vertically long, but otherwise normally shaped, condyles, and disc displacements are more commonly seen in deviated prognathism. Posterior disc displacements occasionally occur.

Our treatment protocol for patients with active CH type 1 includes (1) high condylectomy to arrest the mandibular growth; (2) TMJ disc repositioning over the top of the condyle with a Mitek anchor (see Fig. 6 C, D); (3) bilateral mandibular ramus osteotomies; and (4) maxillary osteotomies and adjunctive procedures if indicated (see Figs. 5 E–H; 6 B). Our studies show that this protocol stops mandibular growth and provides highly predictable and stable skeletal and occlusal outcomes with normal jaw function and good aesthetics. Treating active CH type 1 with orthodontics and/or orthognathic surgery only, without including the high condylectomy, results in a high relapse rate with redevelopment of a class III skeletal and occlusal relationship.

Condylar overdevelopment conditions

Condylar Hyperplasia Type 1

Patients with condylar hyperplasia (CH) type 1 may have a class I occlusion at the beginning of puberty and develop into a class III, or begin as a class III but develop a worse class III relationship with accelerated mandibular growth that can continue into the mid-20s, although it is eventually self-limiting. Bilateral active CH type 1 causes progressive worsening prognathism and occlusion but usually asymptomatic TMJs. Unilateral or bilateral CH type 1 with asymmetric growth can cause progressive deviated prognathism, facial asymmetry, disc dislocations, TMJ pain, headaches, and masticatory dysfunction ( Figs. 5 A–D, 6 A). Not all prognathic mandibles are caused by CH; only those showing accelerated, excessive mandibular growth continuing beyond the normal growth years. MRI may show thin discs that sometimes are difficult to identify; they tend to have vertically long, but otherwise normally shaped, condyles, and disc displacements are more commonly seen in deviated prognathism. Posterior disc displacements occasionally occur.