Alterations to normal oral sensory function can occur following restorative and surgical dental procedures. Paresthesia is defined as an abnormal sensation, such as burning, pricking, tickling, or tingling. Paresthesias are one of the more general groupings of nerve disorders known as neuropathies. This article reviews the extent of this oral complication as it relates to dental and surgical procedures, with specific emphasis on paresthesias associated with local anesthesia administration. This review establishes a working definition for paresthesia as it relates to surgical trauma and local anesthesia administration, describes the potential causes for paresthesia in dentistry, assesses the incidence of paresthesias associated with surgery and local anesthesia administration, addresses the strengths and weaknesses in research findings, and presents recommendations for the use of local anesthetics in clinical practice.

Alterations to normal oral sensory function can occur after restorative and surgical dental procedures. These sensory abnormalities, generally described as paresthesias, can range from slight to complete loss of sensation and can be devastating for the patient. This article reviews the extent of this oral complication as it relates to dental and surgical procedures, with specific emphasis on paresthesias associated with local anesthesia administration. This review establishes a working definition for paresthesia as it relates to surgical trauma and local anesthesia administration, describes the potential causes for paresthesia in dentistry, assesses the incidence of paresthesias associated with surgery and local anesthesia administration, addresses the strengths and weaknesses in research findings, and presents recommendations for the use of local anesthetics in clinical practice.

Definition of paresthesia

What is meant by paresthesia? Stedman’s Medical Dictionary defines a paresthesia as an abnormal sensation, such as of burning, pricking, tickling, or tingling. Paresthesias are one of the more general groupings of nerve disorders known as neuropathies. Paresthesias may manifest as total loss of sensation (ie, anesthesia), burning or tingling feelings (ie, dysesthesia), pain in response to a normally nonnoxious stimulus (ie, allodynia), or increased pain in response to all stimuli (ie, hyperesthesia).

In reviewing the dental anesthesiology literature regarding paresthesias, some confusion exists when describing this as an adverse reaction after the administration of local anesthesia. Depression of nerve function and associated anesthesia are the clinical functions of the local anesthetic agents, and altered sensations, such as dysesthesias, are an expected component of the recovery process following local anesthesia. It is now commonplace to include an element of duration to the definition to permit expected pharmacologic alterations in sensory nerve function to be differentiated from abnormal and potentially permanent adverse reactions. In describing paresthesia as a complication of local anesthesia, the anesthesia or altered sensation is required to “persist beyond the expected duration of action of a local anesthetic injection.”

Most cases of paresthesia that are reported after dental treatment are transient and resolve within days, weeks, or months. The best data regarding rate of recovery are provided in the article by Queral-Godoy and colleagues, in which survival curves are presented for recovery from surgical paresthesias. These data suggest that complete recovery at 8 weeks had occurred in only 25% to 30% of the patients. When reevaluated at 9 months, complete recovery had occurred in 90% of the patients. The time when a paresthesia should be considered permanent is not absolute and is often not known with certainty. Paresthesias that last beyond 6 to 9 months can be described as persistent and are unlikely to recover fully, although some still can. Reports of recovery of sensory function beyond a year are extremely rare.

These persistent neuropathies are the authors’ primary concern. Few treatments are available that effectively improve symptoms or completely correct persistent paresthesias after dental procedures. Microsurgical repairs of traumatic nerve damage after oral surgical procedures have reported some success in obtaining useful sensory recovery or complete recovery of nerve function. Scientific analyses that establish risk factors for the development of paresthesias must continue to be performed, and treatment options that may prevent this potentially serious complication should be disseminated to those practicing the profession.

Reports of paresthesia after dental treatment

Persistent paresthesias are most commonly reported after oral surgical procedures in dentistry. Needle trauma, use of local anesthetic solutions, and oral pathologies have been less frequently documented.

Third Molars

It has been estimated that 5 to 10 million impacted third molars are removed every year in the United States. Peripheral nerve injuries associated with this common oral surgical procedure may be caused by stretching of the nerve during soft tissue retraction, nerve injury caused by compression, as well as partial and complete resection. During removal of third molars, the inferior alveolar nerve (IAN) and the lingual nerve are most likely injured. Bataineh, in reviewing more than 30 reports of nerve impairment immediately after third molar extraction, found that the incidence of lingual nerve paresthesia was 0% to 23% and that of IAN paresthesia was 0.4% to 8.4%. Risk factors for these surgical paresthesias include procedures involving lingual flaps and osteotomies, operator experience, tooth angulations, and vertical tooth sectioning. IAN and lingual nerve sensory impairments are transient and usually recover fully. Recovery has been reported to occur more rapidly during the first months. As indicated in Table 1 , estimates for the prevalence of persistent paresthesias (lasting at least 6–9 months) after third molar extraction range from 0.0% to 0.4%. A recent study evaluating 3236 patients reported that the prevalence of IAN and lingual nerve injury after third molar extractions was initially 1.5% and 1.8% at 1 month, 1.4% and 1.6% at 6 months, and 0.6% and 1.1% at 18 months. Improved surgical procedures and more accurate imaging is likely to limit the risk of this surgical complication.

| Investigators | Total Number of Patients | Initial Paresthesia Number (Rate%) | Persistent Paresthesia Number (Rate%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Queral-Godoy et al | 3513 | 23 (0.65) | 1 (0.02) |

| Genu and Vasconcelos | 50 teeth (25 patients) | 4 (8.0) | 0 (0) |

| Valmaseda-Catellion et al | 946 | 15 (1.5) | 4 (0.4) |

| Bataineh | 741 | 48 (6.4) | 0 (0) |

| Alling | 367,170 | 1731 (0.47) | 81 (0.02) |

| Jerjes et al | 3236 | 48 (1.5) | 20 (0.6) |

Dental Implants

Placement of mandibular dental implants has also been associated with inferior alveolar, lingual, and mental nerve paresthesias. As shown in Table 2 , alterations in nerve function seen initially after mandibular implant placement have been reported to be as high as 37%. Most of these initial events are related to compression of the IAN by the dental implant and can be resolved by removing or repositioning the implant. Persistent alterations in nerve function may also be caused by nerve damage during preparation for the implant placement. Recent recognition of this potential complication has resulted in an increased awareness among practitioners and an apparent decrease in the incidence of this adverse event. Improvements in patient evaluation, treatment planning, and surgical procedures are likely to significantly decrease the occurrence of this complication in the future.

| Investigators | Total Number of Patients | Initial Paresthesia Number (Rate%) | Persistent Paresthesia Number (Rate%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bartling et al | 94 | 8 (8.5) | 0 (0) |

| van Steenberghe et al | 93 | 16 (17.6) | 6 (6.5) |

| Astrand et al | 23 | 9 (39) | 4 (19) |

| Ellies | 212 | 78 (37) | 27 (13) |

| Ellies and Hawker | 87 | 31 (36) | 11 (13) |

Oral Pathologies

Paresthesia after dental procedures may in rare instances be caused by oral pathologies. Reactivation of varicella-zoster virus has been reported in 6 patients who exhibited facial palsy after dental or orofacial treatment. The presence of infection or abscesses may increase the likelihood of neurologic complications after third molar extractions. Infection and associated endodontic treatment have also been implicated as causes of oral paresthesia.

Local Anesthesia Administration

Local anesthesia administration has also been associated with paresthesia ( Table 3 ). There are several proposed mechanisms for paresthesia after local anesthetic injection. These possible causes include hemorrhage into the neural sheath, direct trauma to the nerve by the needle with scar tissue formation, or possible neurotoxicity associated with certain local anesthetic formulations.

| Investigators | Reported Rates a | Comments |

|---|---|---|

| Haas and Lennon, 1995 | 1 in 439,897 cartridges of articaine and 1 in 588,154 cartridges of prilocaine | Overall incidence of 1 in 785,000 cartridges |

| Pogrel and Thamby, 2000 | 1 per 160,571 IAN blocks (all anesthetics) | Inclusion of additional patients interviewed by telephone but not seen increased this estimate to 1 per 26,762. Most patients reported painful injection experience |

| Miller and Haas, 2000 | 1 in 452,000 cartridges of prilocaine, 1 in 550,000 cartridges of articaine, 1 in 2,555,000, for lidocaine, and 1 in 2,620,000 for mepivacaine | Results were consistent with the 1995 Canadian study |

| Rahn et al, 2000 | 1 in 3,200,000 cartridges of articaine | Estimated number of exposures to articaine was 775 million. Data obtained from the manufacturer of articaine |

| CRA Newsletter, 2001 | 2 per 13,000 injections of articaine | Description of both paresthesias suggested trauma as the probable cause |

| Malamed et al, 2001 | 14 in 882 injections of articaine, 3 in 443 injections of lidocaine | Duration of these events was from less than 1 day to 18 days after the procedure. In all cases, the paresthesia ultimately resolved |

| Dower, 2003 | 1 in 220,000 cartridges of articaine | Calculated from published data that articaine had a 20-fold increase and prilocaine had a 15-fold increase in paresthesia compared with lidocaine |

| Legarth, 2005 | 1 in 140,000 cartridges of articaine | 3% prilocaine had no reports of paresthesias |

| Danish Medicines Agency, 2005 | 1 in 3,700,000 injections with articaine | Not all were believed to be permanent |

| Hillerup and Jensen, 2006 | 1 in 957,000 cartridges of articaine | An overall incidence of 1:22,700,000 for all other anesthetics combined |

| Moore et al, 2006; Hersh et al, 2006; Moore et al, 2007 | 1 per 361 subjects (1060 injections) of articaine | Total of 4 clinical trials performed to acquire FDA approval of 4% articaine with 1:200,000 epinephrine. One case of prolonged numbness resolved within 24 hours |

| Pogrel, 2007 | 1 in 20,000 mandibular injections | Whereas prilocaine may have a higher incidence of paresthesias, no disproportionate nerve involvement from articaine was seen |

| Gaffen and Haas, 2009 | 1 in 410,000 injections of articaine, 1 in 332,000 injections of prilocaine | The incidence estimated for lidocaine was 1 in 2,580,000 |

| Garisto et al, 2010 | 1 in 2,070,678 injections of prilocaine, 1 in 4,159,848 injections of articaine compared to 1 in 124,286,050 injections of lidocaine | Spikes in reporting of paresthesias were seen after initial marketing of the prilocaine and articaine |

a For consistency, each reported injection assumes one cartridge of anesthetic.

Local anesthetics are generally considered to be safe drugs. Yet, because of the large number of dental local anesthetic injections administered annually, even rarely occurring adverse events, such as persistent paresthesia, can represent significant morbidity. It has been estimated that dentists in the United States administer more than 300 million cartridges every year. Even using the lowest incidence rates delineated in Table 3 , this could represent nearly 100 patients a year developing this postanesthetic complication.

Local Anesthetic Agents and Formulations Solutions

To obtain Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approval for the introduction of articaine in the United States, a large multicenter randomized clinical trial (RCT) demonstrating its efficacy and safety was performed. The results of this study were published in 2000 and 2001. These reports described the efficacy and safety of articaine in 1325 subjects administered either 4% articaine with 1:100,000 epinephrine or 2% lidocaine with 1:100,000 epinephrine. The study on efficacy showed that articaine was comparable to lidocaine for mandibular blocks and maxillary infiltrations, a finding replicated in the RCTs published since that time. Although sensory alterations lasting beyond the expected period of anesthesia were reported, all alterations were found to be transient and complete recovery of sensory function occurred within days to weeks. The published safety data concluded that the adverse event profile of articaine was similar to that found with lidocaine.

A large epidemiologic study has suggested that the 4% solutions used in dentistry, namely prilocaine and articaine, are more likely associated with reports of paresthesias after local anesthesia administration. Articaine has been available in Germany since 1976 and in Canada since 1983. In 1995, Haas and Lennon conducted a retrospective study evaluating the incidence of paresthesia from 1973 to 1993 in Ontario, Canada. The database accessed was from the insurance carrier that administered malpractice insurance to all licensed dentists in that province. At the time of the study, there were approximately 6200 dentists in Ontario. In their data set, it was assumed that these paresthesias were persistent and lasted much longer than 8 weeks. It was concluded that there was an overall incidence of 1 paresthesia out of every 785,000 injections. Compared with the other local anesthetics, a statistically significant higher incidence was noted when either articaine or prilocaine was used. The lingual nerve was involved in 64% of the cases, with the IAN involved in the vast majority of the remainder. There was no apparent association with any other factor, such as needle gauge. A follow-up study was done using the same methodology with data from 1994 to 1998. For this period, the incidence of nonsurgical paresthesia in dentistry was 1 in 765,000, similar to the previous finding. The conclusions were the same in that prilocaine and articaine were more commonly associated with this event than the other local anesthetics. The lingual nerve was involved in 70% of the cases, with the IAN involved in the vast majority of the remainder. The same database was used to assess nonsurgical paresthesia reports from 1999 to 2008 to see if the findings were consistent with those from 1973 to 1998. Once again, the observed frequencies for reporting paresthesia were greater for both articaine and prilocaine, and the tongue was the most common structure affected, involving 79.1% of the reports, with the lower lip being affected in the majority of the remainder.

These 3 analyses were remarkably consistent in their findings. The estimated incidence of persistent paresthesia from either prilocaine or articaine approximated 1 in 500,000 injections for each drug, which was approximately 5 fold higher than that found with lidocaine or mepivacaine. No reports of paresthesia were associated with bupivacaine.

What articaine and prilocaine have in common is that they are the only 4% solutions used in dentistry. A 4% solution means that the concentration of the drug is 40 mg/mL. The other agents available in dental cartridges in the United States and Canada are all more dilute. Lidocaine is a 2% solution, mepivacaine is either 2% or 3%, and bupivacaine is 0.5%. This information led the authors to consider that it was not the specific drug that was the factor, but maybe the concentration administered.

Articaine was introduced in 2000 in Denmark. A Danish study was conducted, and it used a format similar to the one used by Haas and Lennon in Canada in 1995. Using data from the Danish Dental Association’s Patient Insurance Scheme, the investigators reviewed reports of paresthesia from 2002 to 2004 in that country. During this period, 32 lingual nerve injuries were registered. Articaine had been administered in 88% of the cases, even though it constituted only 42% of the market. Mepivacaine, as the 3% formulation, was given in the other 12% of cases, and it constituted 22% of the market. Lidocaine, with 22% of the market, had no reports of paresthesia. Prilocaine had 12% of the market and no reports of paresthesia. In Denmark, prilocaine is formulated as a 3% solution, as opposed to 4% in the United States and Canada. The incidence of paresthesia was reported to be 1 in 140,000 for articaine and 1 in 540,000 for mepivacaine.

Another recent study used standardized tests of neurosensory function to determine the cause of injection injury to the oral branches of the trigeminal nerve. The investigators concluded from the assessment of these 56 consecutive patients that there was neurologic evidence of neurotoxicity, not mechanical injury, which resulted in irreparable damage. Consistent with previous clinical studies, the lingual nerve was the most common nerve involved, accounting for 81% of the cases, with the IAN making up the rest. There was also a significant difference in the drugs associated with this neurologic injury. In these patients, articaine was shown to contribute to more than a 20-fold increase in reported paresthesia compared with all other local anesthetics combined. The investigators noted a substantial increase in the number of injection injuries since articaine was introduced into the Danish market.

In a prospective US study of 83 patients referred to a tertiary care center with the diagnosis of persistent alterations of sensory function after local anesthesia administration, only prilocaine was associated with a higher-than-expected incidence of paresthesia. This report evaluated patients treated before articaine was introduced in the United States. The findings were consistent with those previously reported. The overall rate of local anesthetic–induced paresthesias was estimated at 1 per 160,571 IAN blocks. In a follow-up report of an additional 57 patients with paresthesias, the investigators concluded that although prilocaine may have a higher incidence of paresthesias, the rate of paresthesias associated with articaine did not seem to be grossly disproportionate to its use.

In Germany, more than 80 million injections of local anesthetics are administered each year. Articaine, which represents 90% of the market, was introduced in 1975. A report of all adverse reactions for articaine collected by the manufacturer during the period 1975 to 1999 found 242 adverse neurologic reactions described as hyperesthesia and paresthesias. The incidence of neurologic adverse effects based on an estimated 775 million injections of articaine given during this period was 1 in 3.2 million.

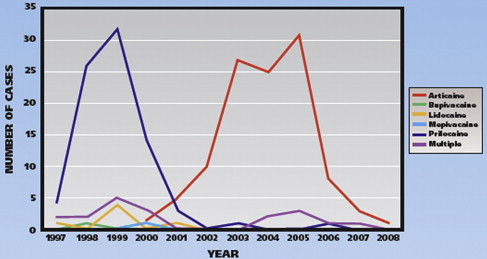

A recent analysis of voluntarily submitted reports of adverse reactions to dental local anesthetics used the FDA’s Adverse Event Reporting System (AERS) computerized information database. Nonsurgical paresthesias reported following local anesthesia administration from November 1997 through August 2008 were evaluated ( Fig. 1 ). Of the 248 cases of nonsurgical paresthesia reported during this period, 89% involved the lingual nerve. The statistical analysis indicated a higher rate of paresthesias associated with prilocaine (1 in 2,070,678) and with articaine (1 in 4,159,848) compared to lidocaine (1 in 124,286,050).

Reports of paresthesia after dental treatment

Persistent paresthesias are most commonly reported after oral surgical procedures in dentistry. Needle trauma, use of local anesthetic solutions, and oral pathologies have been less frequently documented.

Third Molars

It has been estimated that 5 to 10 million impacted third molars are removed every year in the United States. Peripheral nerve injuries associated with this common oral surgical procedure may be caused by stretching of the nerve during soft tissue retraction, nerve injury caused by compression, as well as partial and complete resection. During removal of third molars, the inferior alveolar nerve (IAN) and the lingual nerve are most likely injured. Bataineh, in reviewing more than 30 reports of nerve impairment immediately after third molar extraction, found that the incidence of lingual nerve paresthesia was 0% to 23% and that of IAN paresthesia was 0.4% to 8.4%. Risk factors for these surgical paresthesias include procedures involving lingual flaps and osteotomies, operator experience, tooth angulations, and vertical tooth sectioning. IAN and lingual nerve sensory impairments are transient and usually recover fully. Recovery has been reported to occur more rapidly during the first months. As indicated in Table 1 , estimates for the prevalence of persistent paresthesias (lasting at least 6–9 months) after third molar extraction range from 0.0% to 0.4%. A recent study evaluating 3236 patients reported that the prevalence of IAN and lingual nerve injury after third molar extractions was initially 1.5% and 1.8% at 1 month, 1.4% and 1.6% at 6 months, and 0.6% and 1.1% at 18 months. Improved surgical procedures and more accurate imaging is likely to limit the risk of this surgical complication.

| Investigators | Total Number of Patients | Initial Paresthesia Number (Rate%) | Persistent Paresthesia Number (Rate%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Queral-Godoy et al | 3513 | 23 (0.65) | 1 (0.02) |

| Genu and Vasconcelos | 50 teeth (25 patients) | 4 (8.0) | 0 (0) |

| Valmaseda-Catellion et al | 946 | 15 (1.5) | 4 (0.4) |

| Bataineh | 741 | 48 (6.4) | 0 (0) |

| Alling | 367,170 | 1731 (0.47) | 81 (0.02) |

| Jerjes et al | 3236 | 48 (1.5) | 20 (0.6) |

Dental Implants

Placement of mandibular dental implants has also been associated with inferior alveolar, lingual, and mental nerve paresthesias. As shown in Table 2 , alterations in nerve function seen initially after mandibular implant placement have been reported to be as high as 37%. Most of these initial events are related to compression of the IAN by the dental implant and can be resolved by removing or repositioning the implant. Persistent alterations in nerve function may also be caused by nerve damage during preparation for the implant placement. Recent recognition of this potential complication has resulted in an increased awareness among practitioners and an apparent decrease in the incidence of this adverse event. Improvements in patient evaluation, treatment planning, and surgical procedures are likely to significantly decrease the occurrence of this complication in the future.

| Investigators | Total Number of Patients | Initial Paresthesia Number (Rate%) | Persistent Paresthesia Number (Rate%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bartling et al | 94 | 8 (8.5) | 0 (0) |

| van Steenberghe et al | 93 | 16 (17.6) | 6 (6.5) |

| Astrand et al | 23 | 9 (39) | 4 (19) |

| Ellies | 212 | 78 (37) | 27 (13) |

| Ellies and Hawker | 87 | 31 (36) | 11 (13) |

Oral Pathologies

Paresthesia after dental procedures may in rare instances be caused by oral pathologies. Reactivation of varicella-zoster virus has been reported in 6 patients who exhibited facial palsy after dental or orofacial treatment. The presence of infection or abscesses may increase the likelihood of neurologic complications after third molar extractions. Infection and associated endodontic treatment have also been implicated as causes of oral paresthesia.

Local Anesthesia Administration

Local anesthesia administration has also been associated with paresthesia ( Table 3 ). There are several proposed mechanisms for paresthesia after local anesthetic injection. These possible causes include hemorrhage into the neural sheath, direct trauma to the nerve by the needle with scar tissue formation, or possible neurotoxicity associated with certain local anesthetic formulations.