Poor oral hygiene has been suggested to be a risk factor for aspiration pneumonia in the institutionalized and disabled elderly. Control of oral biofilm formation in these populations reduces the numbers of potential respiratory pathogens in the oral secretions, which in turn reduces the risk for pneumonia. Together with other preventive measures, improved oral hygiene helps to control lower respiratory infections in frail elderly hospital and nursing home patients.

Key points

- •

The oral microflora—and the role of oral care in limiting it—has become recently appreciated; the bacteria that often contribute to initiation of pneumonia have been shown to colonize the oral cavity.

- •

Methods to improve oral hygiene, particularly rinses such as chlorhexidine, can reduce the risk for pneumonia in vulnerable populations.

- •

There is a need to educate both patients and care providers about the importance of oral hygiene to prevent pneumonia.

Introduction

Pneumonia is an inflammatory condition of the lung parenchyma, usually initiated by the introduction of bacteria or viruses into the lower airway. The initiation of pneumonia depends on the aspiration of infectious agents from proximal sites, including the oral and nasal cavities. This disease is particularly prevalent in the elderly, especially those in institutions such as nursing homes, and those with several important risk factors. The role of the oral microflora in this process—and the role of oral care in limiting it—has become much more appreciated over the past decade; the bacteria that often contribute to disease initiation have been shown to colonize the oral cavity.

Pneumonia can be classified according to the location of the origin of the etiologic infectious agents (ie, from the community vs from within the institution—so-called nosocomial pneumonia). One specific form of pneumonia, aspiration pneumonia (AP), is an infectious process caused by the aspiration of oropharyngeal secretions colonized by pathogenic bacteria. This is differentiated from aspiration pneumonitis, which is typically caused by chemical injury after inhalation of sterile gastric contents. AP can also be community acquired or acquired from the health care delivery environment, and it is common in the nursing home setting. AP is almost always caused by a mixed infection, including anaerobic bacteria derived from the oral cavity (gingival crevice), and often develops in patients with elevated risk of aspiration of oral contents into the lung, such as those with dysphagia or depressed consciousness.

This article reviews aspects of the epidemiology, pathogenesis, and prevention of AP. In particular, the role of oral health status in the pathogenesis and prevention of the disease is highlighted.

Introduction

Pneumonia is an inflammatory condition of the lung parenchyma, usually initiated by the introduction of bacteria or viruses into the lower airway. The initiation of pneumonia depends on the aspiration of infectious agents from proximal sites, including the oral and nasal cavities. This disease is particularly prevalent in the elderly, especially those in institutions such as nursing homes, and those with several important risk factors. The role of the oral microflora in this process—and the role of oral care in limiting it—has become much more appreciated over the past decade; the bacteria that often contribute to disease initiation have been shown to colonize the oral cavity.

Pneumonia can be classified according to the location of the origin of the etiologic infectious agents (ie, from the community vs from within the institution—so-called nosocomial pneumonia). One specific form of pneumonia, aspiration pneumonia (AP), is an infectious process caused by the aspiration of oropharyngeal secretions colonized by pathogenic bacteria. This is differentiated from aspiration pneumonitis, which is typically caused by chemical injury after inhalation of sterile gastric contents. AP can also be community acquired or acquired from the health care delivery environment, and it is common in the nursing home setting. AP is almost always caused by a mixed infection, including anaerobic bacteria derived from the oral cavity (gingival crevice), and often develops in patients with elevated risk of aspiration of oral contents into the lung, such as those with dysphagia or depressed consciousness.

This article reviews aspects of the epidemiology, pathogenesis, and prevention of AP. In particular, the role of oral health status in the pathogenesis and prevention of the disease is highlighted.

Epidemiology

Pneumonia is a common disease. Together with influenza, pneumonia was the eighth most common cause of death in the United States in 2011. Classification of pneumonia is based on the residence of the victim at the time of the initiation of the infection. Thus, community-acquired pneumonias are those where the infection is contracted within the community. A recent report found the crude and age-adjusted incidences of pneumonia were 6.71 and 9.43 cases per 1000 person-years (10-year risk was 6.15%). The 30-day and 1-year mortality were found to be 16.5% and 31.5%, respectively. Interestingly, 62% of pneumonia cases occurred in adults older than 65. It is clear that pneumonia is a common disease with severe consequences, especially for the elderly.

Pneumonia occurring in an individual longer than 48 hours after admission to a hospital or other residential health care facility (such as a nursing home) is defined as nosocomial pneumonia.

Pneumonia is the second most common nosocomial infection in the United States (after urinary tract infection), representing 10% to 15% of these infections and is associated with substantial morbidity and mortality, and cost. Most patients who contract nosocomial pneumonia are infants, young children, and persons older than 65; persons who have severe underlying disease, immunosuppression, neurologic deficit, and/or cardiovascular disease; and patients undergoing abdominal surgery.

Over the past decade, as the delivery of medical care has shifted from the hospital to outpatient facilities (for delivery of services such as antibiotic therapy, cancer chemotherapy, wound management, outpatient dialysis centers, etc), the classification scheme for pneumonia has changed. Pneumonia often occurs within such health care delivery settings, but may not be so recognized. For this reason, a new term, health care–associated pneumonia, has entered the literature to describe the range of patients that could be affected.

An important type of health care–associated pneumonia is nursing home–associated pneumonia (NHAP), the most common infection affecting nursing home residents. NHAP is the leading cause of death in the nursing home population. Its incidence among long-term care residents has been variously estimated as 0.7 to 1 episodes per 1000 patient days. Mortality has been estimated to be 8% to 54%. Pneumonia is the most common reason for transfer of nursing home residents to the hospital. However, hospital-based treatment of NHAP is costly, which has driven practitioners to provide treatment in the nursing home rather than after transfer of the patient to the hospital. There is evidence to show that there are no differences in outcomes when comparing NHAP treated by use of oral antibiotics in the nursing home versus parenteral treatment after hospitalization.

Another factor discouraging transfer to the hospital of nursing home residents with pneumonia is that the hospital environment also predisposes to pulmonary infection. Hospital-acquired pneumonia is a common infection in the hospital, often causing considerable morbidity and mortality, as well as extending the hospital stay and increasing the cost of hospital care. Pneumonia is the most common infection in the intensive care unit (ICU) setting, accounting for 10% of infections in the ICU. Hospital-acquired pneumonia can be further divided into 2 subtypes: Ventilator-associated pneumonia (VAP) and non-VAP.

Risk factors

Dysphagia (swallowing dysfunction) is among the most important risk factors for AP. Dysphagia is a relatively common finding in elderly, especially those in nursing homes, where it can be a result of Parkinson disease, Alzheimer disease, stroke, other neurodegenerative conditions, or advanced aging. A recent systematic review that sought to identify risk factors for AP found dysphagia to have a robust positive correlation with AP (odds ratio [OR], 9.84; 95% CI, 4.15–23.33). In a prospective study of 189 elderly veterans residing in a Department of Veterans Affairs nursing home, significant predictors for AP included dependence for feeding, dependence for oral care, tube feeding, current smoking, multiple medical diagnoses, number of medications, and number of decayed teeth. Another study that followed 358 institutionalized veterans aged 55 years and older found significant risk factors for AP for patients with no natural teeth included chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, diabetes, dependence with feeding, and presence of Staphylococcus aureus in saliva. Risk factors for patients with natural teeth included the preceding 4 or more decayed teeth, number of pairs of opposing teeth, and presence of decay—and periodontal disease-causing organisms in saliva or dental plaque, respectively.

A retrospective analysis of 3 states’ Minimum Data Set/Resident Assessment Instrument reports for a 1-year period, representing nearly 103,000 nursing home residents, found the following risk indicators for AP: Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, congestive heart failure, the use of a feeding tube, bedfast status, high case mix (low functionality/high dependency), delirium, weight loss, swallowing problems, urinary tract infection, mechanical diet, dependence for eating, medical immobility, impaired locomotion, number of medications, and age.

More recently, modifiable risk factors for pneumonia in elderly nursing home residents were identified in a prospective study of 613 elderly residents of 5 nursing homes. In this cohort, 18% developed pneumonia. Statistical modeling suggested that inadequate oral care and difficulty with swallowing were associated with pneumonia.

Pathogenesis

Under normal circumstances, the lower airway presents formidable defense against bacteria that are aspirated. A viscous mucous layer coating the epithelium, containing host-derived mucins and antimicrobial components such as lactoperoxidase, lysozyme, and other antimicrobial peptides, traps bacteria, which are then removed from the lung by the mucocutaneous escalator, a function of the unidirectional beating of epithelial cilia. Complex bacterial surface components interact with pattern recognition receptors such as Toll-like receptors to activate inflammation through the nuclear factor-κB signaling pathway. This in turn recruits activated macrophages and neutrophils that engulf the invading bacteria.

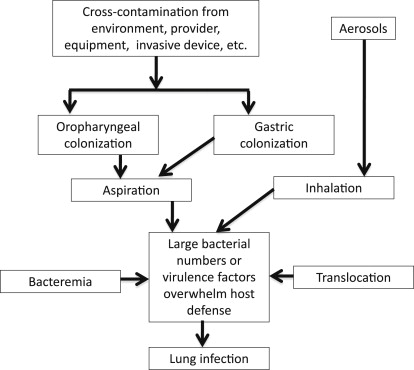

Pneumonia is the result of aspiration of infectious agents colonizing the oral cavity and/or upper respiratory tract. Any condition that compromises upper airway defenses increases the risk for pneumonia by allowing aspirated bacteria to attach to the respiratory epithelium, which then triggers the cascade of events that result in overt infection ( Fig. 1 ). Such conditions include those that reduce containment of the secretions to the upper airway. So, for example, placement of an endotracheal tube through the larynx and trachea into the lung can provide a route for bacteria to bypass those structures that normally prevent aspirations, such as the glottis. Another condition that promotes aspiration is dysphagia, already noted as more common in elderly individuals. Dysphagia is also common in nursing home residents, and therefore represents an important risk factor for AP. Reduction in salivary flow, which occurs frequently in the elderly, most commonly as a side effect of 1 or more medications, also likely contributes to increased risk for pneumonia by allowing enhanced microbial biofilm formation.

It is possible that dysphagia can occur in the absence of overt signs of swallowing difficulty, so-called silent aspiration. Certain conditions, such as stroke or impaired cough reflex, may increase the frequency of such silent aspirations.

In the case of AP, it is likely that most cases are the result of mixed infections involving 2 or more bacterial species, which may be more virulent than infections caused by a single species. Bacteria normally indigenous to the oral cavity can initiate disease, especially anaerobes associated with periodontal disease. Or these species may potentiate the pathogenic potential of other, more typical respiratory pathogens, such as Streptococcus pneumonia, S aureus , or Pseudomonas aeruginosa, which can colonize the oral cavity in high risk subjects such as those in the nursing home. It is well documented that potential respiratory pathogens such as S aureus, P aeruginosa, Klebsiella pneumoniae, and Enterobacter cloacae colonize the dental plaque of dependent elderly. In some health care settings, more than one half the subjects assessed showed the presence of these bacteria in the dental plaque, and prevalence of colonization has been correlated with length of time in the setting.

Oral health and AP

Before the mid 1990s, the role of oral conditions in the pathogenesis of AP, particularly poor oral hygiene and periodontal inflammation, was mostly ignored in the medical and nursing care setting, although it was understood that the source of the infectious agents causing the disease was often the oral microflora. This situation began to change as knowledge of the specific role of the oral microflora in the pathogenesis of pneumonia became available. Much of the work at this time was performed in hospitalized patients, particularly mechanically ventilated patients in the ICU, who have substantially elevated risk for pneumonia. It was shown that the teeth serve as a reservoir for respiratory pathogen colonization, and thus serve as a source of bacteria in aspirated secretions. Further studies also suggested that methods to improve oral hygiene in these populations could reduce their risk of pneumonia.

Several other studies suggested that the oral cavity might also serve as a reservoir for pulmonary infection in nursing home residents. Again, the oral cavities of elderly residents of nursing homes were more frequently found to harbor respiratory pathogens than those of ambulatory patients.

There is some evidence that periodontal disease may be associated with risk for pneumonia in elderly patients. A study of an elderly Japanese population found that the adjusted mortality owing to pneumonia was 3.9 times higher in persons with 10 or more teeth with a probing depth exceeding 4 mm (ie, with periodontal pockets) than in those without periodontal pockets.

In light of these findings, it seems intuitively obvious that oral hygiene or periodontal therapy would help to prevent the onset or progression of AP in high-risk patients. Indeed, a number of studies, described herein, have tested this hypothesis.

Oral care to prevent AP

Most of the available literature addressing the role of oral care in the prevention of pneumonia has been conducted in hospitalized and mechanically ventilated patients. However, several studies have also been conducted in nursing home patients. These studies have been critically reviewed in several recent, systematic reviews of the literature. Taken together, the evidence supports the link between poor oral health and pneumonia. Oral interventions to reduce pulmonary infections have been examined in both mechanically ventilated ICU patients and nonventilated elderly patients. A variety of oral interventions have been tested, including topical antimicrobial agents such as chlorhexidine (CHX) and betadine. Fewer studies have evaluated the effectiveness of traditional oral mechanical hygiene. The use of oral topical CHX reduces pneumonia in mechanically ventilated patients, and may even decrease the need of systemic IV antibiotics or shorten the duration of mechanical ventilation in the ICU. Also, oral application of CHX in the early postintubation period lowers the numbers of cultivable oral bacteria and may delay the development of VAP. Not all studies support the effectiveness of oral CHX in reducing pneumonia, however. The efficacy of oral CHX decontamination to reduce pneumonia requires further investigation.

Several studies have demonstrated that mechanical oral care, in some cases in combination with povidone iodine, significantly decreases the risk of pneumonia in nursing home residents. Once-a-week professional oral cleaning significantly reduced influenza infections in an elderly population.

Implementation of professional oral care programs in nursing facilities involving the deployment of dental hygienists to provide direct oral care, including tooth, tongue, and denture brushing, may help to reduce the oropharyngeal microbial burden, and therefore the number of microbes that can be aspirated into the lower airway. Such an approach may also reduce the risk of other respiratory infections such as influenza.

Oral cleansing reduces pneumonia in both edentulous and dentate subjects, suggesting that oral colonization of bacteria contributes to nosocomial pneumonia to a greater extent than periodontitis per se. However, intervention studies on the treatment of periodontitis on the incidence of pneumonia have not been performed owing to the complexities required in investigating ICU or bed-bound nursing home patients. In edentulous patients, dentures could conceivably serve as a similar reservoir as teeth for oral and respiratory bacterial colonization if not cleaned properly on a daily basis, although neither removable dentures nor the edentulous oral cavity provide the anaerobic environments favored by periodontopathic organisms.

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses