Despite the known influence of early treatment on the facial appearance of growing patients with skeletal Class III malocclusion, few comparative reports on the long-term effects of different treatment regimens (1-phase vs 2-phase treatment) have been published. Uncertainty remains regarding the effects of early intervention on jaw growth and its effectiveness and efficiency in the long term. In this case report, we compared the effects of early orthodontic intervention as the first phase of a 2-phase treatment vs 1-phase fixed appliance treatment in identical twins over a period of 11 years. Facial and dental changes were recorded, and cephalometric superimpositions were made at 4 time points. In spite of the different treatment approaches, both patients showed identical dentofacial characteristics in the retention phase. Through this case report, we intended to clarify the benefits of undergoing 1-phase treatment against 2-phase treatment protocols for treating growing skeletal Class III patients.

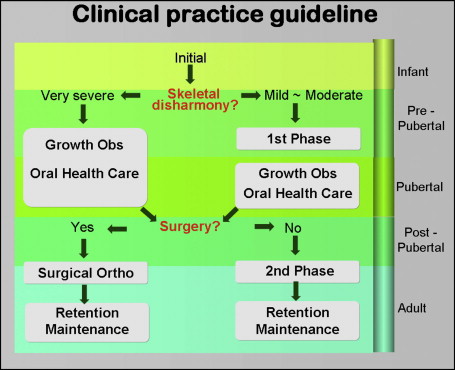

In the treatment of skeletal Class III growing patients, it has become a common practice to intervene early with orthodontic or orthopedic treatment modalities as a part of a 2-phase treatment approach. This approach is claimed to provide early and significant improvement in the facial profile, require fewer surgical interventions in the future, and produce significant psychosocial benefits for the patient as well as the parents. Although orthopedic forces that attempt to control or alter the skeletal framework in skeletal Class III patients appear to be remarkably effective in the initial stages, the results are rarely maintained in the long term. Previously, we presented a clinical practice guideline for the treatment of developing Class III malocclusions ( Fig 1 ). However, it is still difficult to decide whether a 2-phase treatment is actually better than a 1-phase treatment, especially in light of mounting evidence that patients with a skeletal Class III malocclusion show neither excessive mandibular growth nor deficient maxillary growth when compared with Class I subjects at any growth stage. Therefore, the key question is “what differences in jaw growth or treatment modality and outcome will there be between patients who undergo 1-phase treatment and those who don’t?” This twin study allowed us to elucidate some benefits of 1-phase treatment rather than waiting until the postadolescent period.

Diagnosis and etiology

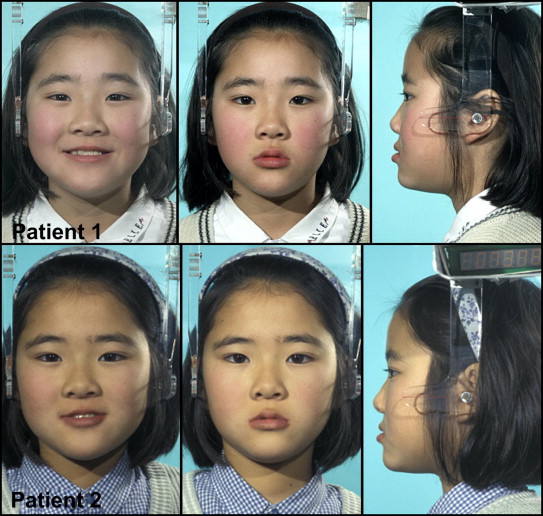

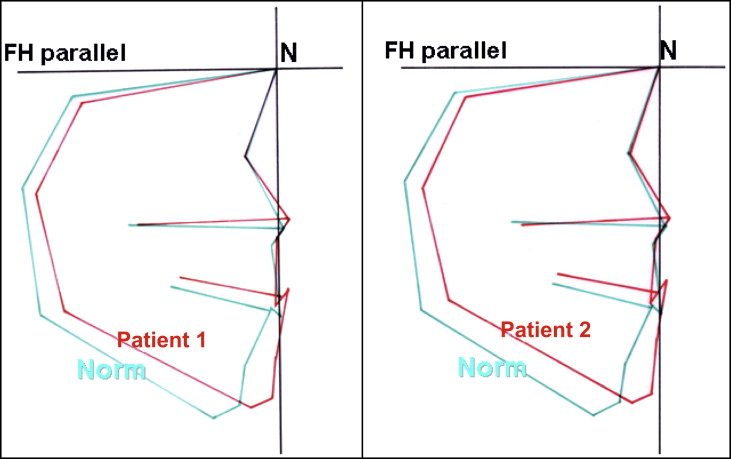

The patients, monozygotic twin sisters ( Fig 2 ), were referred to our department at Tohoku University, Sendai, Japan, in 1996 when they were 9 years old for orthodontic treatment of anterior crossbites. Their medical histories showed no systemic diseases or developmental anomalies. Not surprisingly, both twins had almost the same orthodontic problems that included a prognathic profile, mild mandibular asymmetry, Class III denture bases, deviation of mandibular midlines, and occlusal interference of the incisors ( Fig 3 ). Cephalometrically, their skeletofacial types were classified as Class III short-face types. The short-face tendency was more pronounced in Patient 2 ( Fig 4 ).

Treatment objectives

Class III short-face skeletofacial types are considered to have a good prognosis, because their mild jaw disharmony allows downward and backward rotation of the mandible for correction of the anterior crossbite and deepbite and, therefore, are good candidates for a treatment plan involving 2 phases. This includes correction of the anterior crossbite in the first phase followed by a period of growth observation and then a second phase of treatment with fixed appliances. In light of our previous discussion regarding early intervention on jaw growth, the treatment objectives for Patient 1 were established with the 2-phase treatment approach, whereas Patient 2 was managed with a 1-phase treatment concept. Informed consents were obtained for both patients from their parents.

The treatment objectives for Patient 1 were (1) phase 1 treatment involving dental correction of the anterior crossbite, (2) growth monitoring and oral health care until the postadolescent period, (3) fixed appliance treatment for correction of the remaining orthodontic problems, and (4) retention and long-term follow-up.

For Patient 2, the treatment objectives were (1) growth monitoring and oral health care until the postadolescent period, (2) correction of the malocclusion with fixed appliance treatment together with skeletal anchorage that would allow us to circumvent the need for mandibular premolar extraction, and (3) retention and long-term follow-up.

Treatment objectives

Class III short-face skeletofacial types are considered to have a good prognosis, because their mild jaw disharmony allows downward and backward rotation of the mandible for correction of the anterior crossbite and deepbite and, therefore, are good candidates for a treatment plan involving 2 phases. This includes correction of the anterior crossbite in the first phase followed by a period of growth observation and then a second phase of treatment with fixed appliances. In light of our previous discussion regarding early intervention on jaw growth, the treatment objectives for Patient 1 were established with the 2-phase treatment approach, whereas Patient 2 was managed with a 1-phase treatment concept. Informed consents were obtained for both patients from their parents.

The treatment objectives for Patient 1 were (1) phase 1 treatment involving dental correction of the anterior crossbite, (2) growth monitoring and oral health care until the postadolescent period, (3) fixed appliance treatment for correction of the remaining orthodontic problems, and (4) retention and long-term follow-up.

For Patient 2, the treatment objectives were (1) growth monitoring and oral health care until the postadolescent period, (2) correction of the malocclusion with fixed appliance treatment together with skeletal anchorage that would allow us to circumvent the need for mandibular premolar extraction, and (3) retention and long-term follow-up.

Treatment alternatives

Because the twins were skeletal Class III growing patients, growth modification treatments and functional appliances could be alternatives, but they were not included with our options for the reasons previously mentioned.

Treatment alternatives in the postadolescent phase could have included conventional camouflage treatment with a multi-bracketed system and premolar extractions together with Class III elastics. This approach would improve the Class III occlusion, but it would undermine esthetics, resulting in a more protruded chin and concave profile. Orthognathic surgery is also a viable option for improving function, occlusion, and esthetics; however, our patients rejected surgery as an option.

Treatment progress

Although a 1-phase treatment protocol was chosen for Patient 2, there was no definitive treatment until growth completion was confirmed. In Patient 1, the first phase of treatment began with facemask therapy and 2 × 4 appliances. The aim was to correct her anterior crossbite dentally, not skeletally. The crossbite and maxillary dental midline shift were corrected in 6 months.

At the age of 10 and after the first phase of treatment, Patient 1’s prognathic profile and dental malocclusion had improved significantly. At the same time, growth observation in Patient 2 showed that all her orthodontic problems were exactly as they had been at the initial examination. At age 13, both twins had completed their permanent dentitions. Patient 1 had maintained a positive overjet and overbite after the first phase of treatment, whereas Patient 2 showed a slight improvement in her deepbite without orthodontic intervention. Both sisters had the possibility of postpubertal growth of the mandible; therefore, we decided to elongate the growth observation period until 16 years of age as per our clinical practice guidelines.

Before the second phase of treatment, Patient 1 still had a prognathic profile, with some minor dental problems, particularly in the mandibular dentition. She had a lateral crossbite on the right side, a mild Class III denture base, and mild mandibular incisor crowding. At the same stage, Patient 2 demonstrated more severe orthodontic problems than her sister did at this age. She had a skeletal Class III malocclusion with a short-face tendency, premature contact at the incisors, a dental midline shift, an anterior crossbite, severe crowding of the maxillary anterior teeth, and retroclined mandibular incisors.

At this stage, we superimposed the cephalometric radiographs from 9 and 16 years of age based on the natural reference structures suggested by Skieller et al and Björk and Skieller. Cephalometric tracings were made in detail and superimposed carefully. In Patient 1, the superimposition showed correction of the anterior crossbite, with a significant amount of jaw growth. However, the amount of jaw growth from 13 to 16 years of age was negligible. In Patient 2, the cephalometric superimpositions showed that the maxilla and the mandible had significant amounts of downward and forward growth during the adolescent growth period. Her overbite had improved over time.

To correct the rest of Patient 1’s orthodontic problems, preadjusted fixed appliance treatment was started, and short Class III elastics were used to improve the Class III denture bases and prevent proclination of the mandibular incisors during leveling and aligning. Treatment for Patient 2 started with bonding brackets on the mandibular teeth and placing resin caps on the maxillary molars to open the bite for maxillary bonding. Open-coil springs were used to make space and procline the maxillary incisors. Simultaneously, distalization of the mandibular posterior teeth was started with the skeletal anchorage system, which uses an orthodontic miniplate as a temporary anchorage device. Within several months, her anterior crossbite was completely corrected, and the distalized mandibular posterior teeth were retained with the help of ligature wires connected to the miniplates.

After 12 months of active fixed appliance treatment, Patient 1’s malocclusion was corrected. She obtained a balanced profile, with adequate overjet and overbite, proper anterior guidance, and rigid posterior intercuspation of the teeth. On the other hand, Patient 2’s treatment with the skeletal anchorage system lasted 18 months. She also achieved an acceptable Class I occlusion and a satisfactory profile at debonding.

The dentofacial changes during the second phase of treatment were minimal in Patient 1; only the uprighting of the mandibular molars was observed. On the other hand, the cephalometric superimposition in Patient 2 before and after treatment with the skeletal anchorage system showed that her anterior crossbite was largely corrected by proclination of the maxillary incisors and clockwise rotation of the mandible, causing extrusion of her maxillary and mandibular molars. The mandibular molars were slightly distalized, and the retroclination of her mandibular incisors was improved purely by lingual root torque. After 30 months of retention, both twins have maintained a good occlusion except for a minor relapse of the maxillary right first premolar in Patient 2. Overall, satisfactory results were achieved.

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses