Chapter 1

New Directions

Primary care is undergoing a radical transformation from physician-centered practices to team-based patient-centered care. Amid the upheaval, this is spawning real innovation as healthcare organizations across the nation challenge themselves to reduce waste and provide more effective care and—most important—to document and measure health outcomes with robust IT systems. States have some leeway in determining how they wish to handle newly insured Medicaid beneficiaries and even if they wish to participate at all in the state health insurance exchange program. If they do not, Medicaid enrollees will be eligible to join through an exchange created by the federal government. One thing is certain: This is a massive undertaking and the regulations are voluminous, the “shared savings” with Medicare and Medicaid—the incentive payments for meeting the targets—are complex beyond measure, and this bold experiment is going to provide a lot of work for analysts and financial consultants. But isn’t it great that people with preexisting conditions will now be able to buy insurance and the many Americans who are uninsured will now be able to buy a basic level of coverage?

When the dust settles from all the chaos, there should be huge benefits in the areas of patient safety, proactive coordination of care for those with chronic conditions, and reduced hospitalization and visits to the ED due to the focus on prevention. In theory, if patients have access to primary care, most of their conditions can be dealt with in a low-cost setting and in a timely manner, before they ramp up to requiring more expensive procedures. This will save money and reduce the escalation of healthcare expenditures. A thoughtful exploration of healthcare reform delving into specific (and often amusing) examples of the ineffectiveness of our current system will be of interest to anyone wondering about how we got to this point and how we can get better healthcare for half the cost.1 The writing style makes it a page-turner as its author, Joe Flower, untangles the many forces that have resulted in our current system, but he ends with optimism.

ACO QUALITY METRICS

Accountable care organizations (ACOs) will be assessed by 65 quality metrics spanning five equally weighted domains: patient and caregiver experience, care coordination, patient safety, preventive health, and care for frail elderly and at-risk populations.2

A SAMPLING OF INNOVATION

Innovation occurs in small and large settings as can be seen in the examples below, starting with Oregon’s five-year Medicaid experiment to test whether coordinated care can deliver better health at lower cost. Next, a project at the Mayo Innovation Center looks at outpatient obstetrical care and better ways to provide continuity between scheduled visits. Last, a two-physician family practice takes bold steps to redesign care with a new office that is iconoclastic in its concept and aesthetically stunning as well.

Oregon’s Medicaid Transformation

The cover story in Modern Healthcare shouts “Kitzhaber’s Gamble: Oregon makes risky bet on fixed-budget ACOs to curb Medicaid costs.”3 A year into Oregon’s five-year plan, 16 Coordinated Care Organizations (CCOs) are caring for 90 percent of Medicaid beneficiaries using a patient-centered medical home model. CCOs receive per capita monthly payments for care delivered in this pilot program that is underwritten by $1.9 billion in federal funding from the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS). The provider organizations must include dental and mental healthcare and focus on chronic conditions, including addiction problems and mental illness. A principal goal is to transition from costly fee-for-service to a program that emphasizes primary and preventive care. This requires social workers, nurses, medical assistants, and physicians to work together to systematically keep track of complex patients to anticipate their needs and reach out to them for adjustments to medications and to get them to the clinic for preventive care. These are the patients who end up in the ER repeatedly if not closely managed.

Governor Kitzhaber negotiated a waiver with the CMS to get funding to kick off this initiative and, in return, the deal requires progress on 33 quality and access measures. The program is not without controversy from those who wonder if a capitated payment will cause providers to stint on care, and hospitals express concern that success will result in a reduction in admissions. This is a bold plan in the national spotlight. Several other states are proposing to follow Oregon’s lead, and only time will tell whether it is possible to get a handle on soaring healthcare costs and, at the same time, improve the health and well-being of Americans.

Mayo OB Nest: Redesigning Continuity of Care

A project undertaken at the Mayo Innovation Center was the study of outpatient OB care.4 They realized that the current schedule of appointments was based on a provider-centric sense of continuity that did not address what happens between visits, and this may even be more important to patients. Looking at ways to give mothers the opportunity to tap into their own knowledge base—to be able to validate their wisdom—led to experimentation with different options. Patients were given the ability to text a nurse, and to be able to Skype in for a patient visit. They were given portable Doppler devices to be able to listen to the baby’s heartbeat to help build the mother’s sense of confidence. This continual feedback loop is designed to reduce the bottleneck around the scheduled appointments and allow mothers to enjoy a sense of well-being, rather than stress.

Village Family Medicine

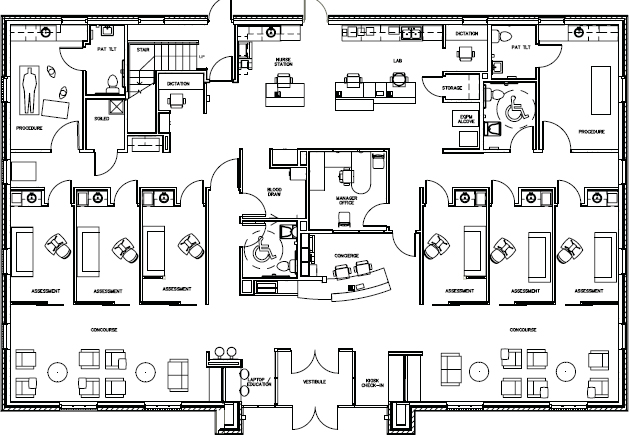

Breaking the mold for primary care practices led the two physicians who formed this practice to examine the patient encounter to see how they could improve the patient experience. To begin with, they have a same-day appointment policy and most visits are 30 minutes from arrival to checkout. As they worked with their architects to program the space, they realized that 85 percent of patients did not need to sit on an exam table during the visit. Instead, they developed assessment rooms (Figure 1-1) that serve for everything except minor procedures or disrobing. The following functions occur in this room:

Figure 1-1. Assessment examination room at Village Family Medicine, Spartanburg, South Carolina.

- Registration

- Check vitals (BP, height, weight, pulse, O2)

- Immunizations, injections

- Collect patient history, discuss reason for visit

- Diagnosis: perform tests such as EKG, spirometry, tympanometry in office, and order other tests; access point-of-care databases

- Patient education: provider advice, coaching, handouts printed from EHR

- Referrals, checkout, and payment; book future appointment

The background for this project is interesting in that this medical practice is part of a large system, Spartanburg Regional Health System in Spartanburg, South Carolina, and they are also a member of Spartanburg Regional Physicians Group, a large multispecialty group. The lead physician was given considerable latitude in the design of this facility with the goal that it would become a prototype for the system. It opened in January 2011. The design was influenced by the Disney concept of on-stage/off-stage and the emphasis on creating a great experience. In the space plan (Figure 1-2), there are dual entries to the assessment rooms with staff entering from a rear corridor adjacent to the nurse station and lab (see Figure 3-65) and patients entering through acoustically sealed sliding barn doors off of what is called the “concourse.” Patients are able to check themselves in upon arrival at a kiosk. Other influences in the design were based on the architects’ analysis of retail models with a strong customer-centric philosophy such as Apple and Nordstrom. In addition, students from Clemson University Architecture + Health posed as mystery shoppers, visiting three or four family practice locations in the health system to enable them to experience the care and to make suggestions for improvement. Last, NXT Health, a nonprofit organization with leadership from Clemson University’s Architecture + Health master’s degree program graduates, participated in the project. Innovation through collaboration is the goal of NXT Health.

Figure 1-2. Space plan, Village Family Medicine, 5,680 square feet.

The interior design of the office is contemporary with finishes in various neutral colors that have enough contrast to avoid being bland (Figure 1-3). The pattern in the flooring is no-wax, vinyl plank. The distressed appearance was selected to reflect the history of the area, which was farming and horse land.

Figure 1-3. Waiting room, Village Family Medicine.

BUILDING BLOCKS OF HIGH-PERFORMING PRIMARY CARE

Across the nation, primary care is being transformed from physician-centered practices to patient-centered teams. To better understand the dynamics of this change, Rachel Willard, MPH, and Tom Bodenheimer, MD, studied seven high-performing large primary care practices in California, Oregon, Washington, and Colorado, doing research that involved extensive site visits and interviews with the leadership and all levels of staff at these organizations.5 “High-performing” was defined as having high levels of patient and staff satisfaction, a stable financial base, and clinical quality metrics that have improved over time.

Six building blocks were considered essential for success in the new model of healthcare delivery by the seven organizations studied. Readers are encouraged to read the entire white paper as it has many specific examples of innovation and an extensive reference list.

- Data-driven improvement. Collect, clean, and summarize performance data for use by clinicians to drive effective action. “Data provide the bedrock of high-performing health practices….”

- Empanelment and panel size management. Assign patients to a clinician and team in the process of empanelment, actively manage panel size, balancing capacity and demand to maintain continuity of care.

- Team-based care. Includes front-desk personnel, clinicians, MAs, RNs, psychologists, social workers, and the like. Rely on clear vision and principles, working in shared space, using well-honed communication skills and defined workplans.

- Population management. Patients with complicated medical and psychosocial needs receive a different level of care and management. Employ health coaching for patients with chronic diseases. Use panel management to support the preventive care needs of all patients.

- Continuity of care. Improves quality of care, the patient’s experience, and lowers costs. Actively control panel size to ensure demand does not exceed supply.

- Prompt access to care. Timely access cannot be achieved without managing panel size to balance capacity and demand. Strategy: Open the schedule only a few weeks at a time, space visits by taking care of more needs at each visit, and offer phone visits, Web-based patient portals, group visits, and visits with nonclinician team members.

THE SMARTPHONE WILL SEE YOU NOW: THE mHEALTH REVOLUTION

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses