In surveys of oral and maxillofacial surgery practice, removal of teeth is the most frequently performed operation. Removal of an impacted mandibular third molar tooth (M3) presents unique surgical challenges. One such challenge is the risk of injury to the peripheral branches of the trigeminal nerve, which provide sensation to the oral and facial regions. Indeed, in the practice of oral and maxillofacial surgery, because of their unfavorable effects on orofacial sensation and related functions (such as eating, drinking, washing, speaking, shaving, kissing), nerve injuries are currently the most frequent cause of litigation against oral and maxillofacial surgeons (OMFSs) in the United States. Since the seminal work of Merrill in the 1960s to 1970s on the injury, pathophysiology, and repair of inferior alveolar and lingual nerve (LN) injuries, much research and clinical work has been directed toward the prevention and treatment of peripheral trigeminal nerve injuries.

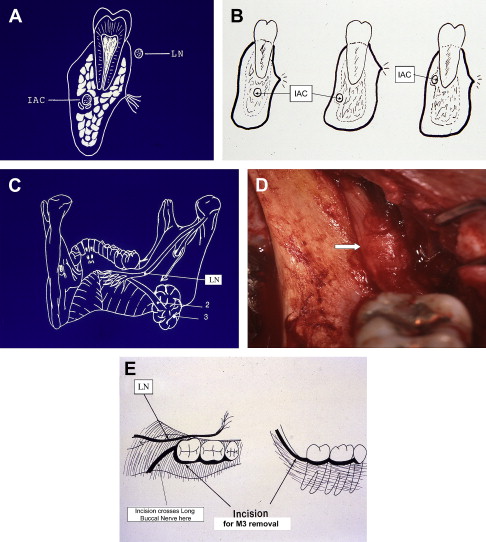

During the removal of an M3, the inferior alveolar nerve (IAN), lying adjacent to M3’s roots, and the LN, often located just medial to M3’s crown at or near the mandibular lingual alveolar crestal bone, are at risk of injury from the various surgical maneuvers composing the operation. Such injuries may not resolve in a reasonable period but instead persist and result in significant permanent sensory dysfunction in the distribution of the involved nerve. On the other hand, the long buccal nerve (LBN) is frequently knowingly transected during the standard incision for exposure of the M3, but only rarely does this maneuver cause bothersome sensory aberration ( Fig. 1 ).

Nerve injury is a known and accepted risk of the removal of M3s and it may occur despite the best of care. Proactive measures during evaluation and removal of M3s may reduce the incidence of nerve injury and the disturbance of sensory alteration. When nerve injury caused by the removal of an M3 fails to resolve promptly and the resulting paresthesias and/or dysesthesias are unacceptable to the patient, timely treatment gives the patient the best chance of a favorable outcome.

Incidence

Various retrospective reports from individual surgical practices in the literature have given only a limited sample of the incidence or frequency of nerve injuries related to removal of M3s. From this information it had been estimated that a temporary injury to the IAN or LN occurred in 1.0% to 4.4% of patients, with 0.1% to 1.0% of the injuries failing to resolve and becoming permanent in the absence of treatment. New data in 2005 obtained from 535 responses (95% of membership) in a survey of the California Association of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgeons have provided a more comprehensive view of this problem. In 95% of surgeons’ practices, 1 or more patients per year sustained an IAN injury (78% of the injuries were classified as permanent), whereas 1 or more LN injuries were reported in 53% of practices (46% of the injuries deemed permanent). Mean rates for all injuries per thousand M3s removed were 0.4% for IAN injuries (4/1000) and 0.01% for LN injury (1/1000), whereas the permanent injury rates were 0.04% (1/2500) for the IAN and 0.010% (1/10,000) for the LN. The cause of IAN injury was known (although not specified) in 261 respondents; on the other hand, only 31 surgeons knew the cause of LN injury. This may be because of the visualization of the IAN in the depths of an M3 socket after tooth removal, whereas the LN is often contained within the lingual soft tissue flap and could not be directly observed by the surgeon. Unsurprisingly, injury rates by surgeons were lower among those surgeons performing greater numbers of extractions per year (range, 100–2000) and having more years of experience.

Not all M3s are removed by specialists. No recent hard data are available for nerve injury complication rates among general dental practitioners (GDPs) who remove M3s. At present, it is estimated that approximately 50% of M3s are extracted by GDPs in the United States. In the authors’ combined clinical experience of more than 40 years of caring for nerve injuries, the number of nerve injury referrals from OMFSs and GDPs are approximately equal. However, there may be a bias in that GDPs tend to do the easier cases and refer all others to OMFSs, including those with higher known risk of nerve injury (ie, proximity of M3 roots to inferior alveolar canal [IAC] as seen on a radiograph).

Cause

Removal of M3s is the procedure most frequently associated with nerve injuries in oral and maxillofacial surgery practice ( Box 1 ). However, the exact cause of nerve injury is frequently not known, especially if the involved nerve is not directly visualized during removal of M3s. Indirect deduction from imaging studies on the relationship of the tooth roots to the IAC provides indicators of likelihood of injury to IAN. Because the LN resides in soft tissue and most preoperative evaluations for M3 removal do not include imaging with MRI, no data exist to guide the clinician on estimating the LN position or risk of injury. (See the article by Miloro in this issue for further exploration of this topic.)

- •

Removal of lower third molar teeth

- •

Orthognathic surgery

- •

Maxillofacial trauma (fractures, soft tissue injury, gunshot wound)

- •

Dental implants

- •

Cyst or tumor excision

- •

Preprosthetic surgery (vestibuloplasty, ridge augmentation)

- •

Root canal treatment (canal filling, apical surgery)

- •

Local anesthetic injection

- •

Salivary gland excision

- •

Biopsy

Speculation on the cause of nerve injury in a given patient is often a reflection of whether the discussant is the surgeon (unexpected or rare anatomic variation, unavoidable mishap despite the best of care) or a disgruntled patient (error in surgeon’s technique, not adhering to a standard procedure). From the authors’ personal experience in the removal of M3s and in caring for patients referred for nerve injury treatment, several aspects of the operation for M3 removal seem, either by inference or direct observation, to pose a risk for injury to the IAN, LN, or LBN. These maneuvers include injection of a local anesthetic, location of the incision, retraction of a soft tissue flap for access to the tooth, removal of associated soft tissue pathology (eg, enlarged follicular sac or cyst, periapical inflammatory/granulation tissue), removal of bone, tooth sectioning, suturing, and administration of medications (either after removal of the tooth [ie, antibiotic] or in the postoperative period for treatment of alveolar osteitis [dry socket]). Whether these risk factors can be overcome by proactive modification of techniques or procedures is a matter of conjecture in any given patient. However, each of these risk factors is discussed in the following section, along with suggestions for the reduction of the risk of nerve injury.

Cause

Removal of M3s is the procedure most frequently associated with nerve injuries in oral and maxillofacial surgery practice ( Box 1 ). However, the exact cause of nerve injury is frequently not known, especially if the involved nerve is not directly visualized during removal of M3s. Indirect deduction from imaging studies on the relationship of the tooth roots to the IAC provides indicators of likelihood of injury to IAN. Because the LN resides in soft tissue and most preoperative evaluations for M3 removal do not include imaging with MRI, no data exist to guide the clinician on estimating the LN position or risk of injury. (See the article by Miloro in this issue for further exploration of this topic.)

- •

Removal of lower third molar teeth

- •

Orthognathic surgery

- •

Maxillofacial trauma (fractures, soft tissue injury, gunshot wound)

- •

Dental implants

- •

Cyst or tumor excision

- •

Preprosthetic surgery (vestibuloplasty, ridge augmentation)

- •

Root canal treatment (canal filling, apical surgery)

- •

Local anesthetic injection

- •

Salivary gland excision

- •

Biopsy

Speculation on the cause of nerve injury in a given patient is often a reflection of whether the discussant is the surgeon (unexpected or rare anatomic variation, unavoidable mishap despite the best of care) or a disgruntled patient (error in surgeon’s technique, not adhering to a standard procedure). From the authors’ personal experience in the removal of M3s and in caring for patients referred for nerve injury treatment, several aspects of the operation for M3 removal seem, either by inference or direct observation, to pose a risk for injury to the IAN, LN, or LBN. These maneuvers include injection of a local anesthetic, location of the incision, retraction of a soft tissue flap for access to the tooth, removal of associated soft tissue pathology (eg, enlarged follicular sac or cyst, periapical inflammatory/granulation tissue), removal of bone, tooth sectioning, suturing, and administration of medications (either after removal of the tooth [ie, antibiotic] or in the postoperative period for treatment of alveolar osteitis [dry socket]). Whether these risk factors can be overcome by proactive modification of techniques or procedures is a matter of conjecture in any given patient. However, each of these risk factors is discussed in the following section, along with suggestions for the reduction of the risk of nerve injury.

Prevention

It may or may not be possible to reduce the number of risk factors for nerve injury during the removal of M3. However, even in an operation that meets all standards of care and is performed by a well-trained and experienced OMFS, it is known and accepted that risks and complications can still and do occur. The following suggestions are presented without certainty as to their success in minimizing the risk of nerve injury.

Imaging Studies

Imaging studies are the basis for evaluation of contemplated M3 removal. An adequate radiograph should display the entire tooth, surrounding bone, periapical region, and IAC. This visualization may be possible with a periapical film, but a panoramic view is most commonly used as a basic imaging study ( Fig. 2 ). In addition to the depth of M3 within the mandible (soft tissue, partial bone, and complete bone impaction), and the angulation of the tooth within the alveolar bone (vertical, horizontal, mesioangular, distoangular), perhaps, the most important information is the position of the tooth roots in relation to the IAC. In determining this relationship from a plain radiograph, which shows overlap of the IAC and the tooth roots, 2 factors are assessed: (1) the radiodensity of the root where it is overlaid by the IAC and (2) the width (diameter) of the IAC as it crosses over the roots. Four conditions can be identified: (1) superimposition , in which the roots and IAC are overlaid in the 2-dimensional radiograph but are actually not in physical contact or proximity; (2) notching of the root, in which the IAC is in intimate physical contact within an indentation in the side of the root; (3) grooving , in which the IAC is in intimate contact within a concave defect in the apex of the root; and (4) perforation , in which the IAC actually penetrates through the root ( Fig. 3 ). There will be little or no loss of radiodensity of the root, which is superimposed on the IAC as seen in a plain radiograph, but is not in actual contact. When the root has been notched, grooved, or penetrated by the IAC, however, there will be a definite line of demarcation indicating a change in root radiodensity. Additionally, when the IAC penetrates the M3 root, the IAC width (diameter) generally narrows noticeably. Conditions other than superimposition might require further evaluation with a computed tomographic scan ( Fig. 4 ). Documentation of notching, grooving, or penetration of the root may be an indication to perform subtotal removal of the tooth, avoiding the portion of the root that is in intimate contact with the IAC (see Coronectomy under Treatment).

Injection of a Local Anesthetic

Injection of a local anesthetic into the pterygomandibular space for operative anesthesia of the IAN, LBN, and LN and early postoperative pain control is most often done after the patient is under intravenous sedation or general anesthesia. Therefore, the paresthesia (sudden shocking sensation, often with radiation of pain to the teeth, jaw, lower lip, or tongue) that might occur if the injection needle contacts the nerve is not observed. However, if the usual preinjection aspiration returns blood into the anesthetic carpule, it can be assumed that the needle has contacted the IAN and/or LN. Before proceeding with the injection, the needle should be withdrawn 2 to 3 mm, and then the aspiration is repeated. If no blood returns into the carpule, the injection can proceed. When a conscious patient notes a paresthesia, the same routine of slight withdrawal of the needle and aspiration before proceeding is done. The incident is noted in the patient’s record, and a follow-up evaluation of sensory function is done at the first postoperative visit (see the article by Meyer and Bagheri elsewhere in this issue for further exploration of this topic).

Soft Tissue Incision

A correctly placed soft tissue incision avoids trauma to the LN ( Fig. 5 ). The posterolateral extension of the incision routinely crosses the path of the LBN (see Fig. 1 E) making trauma to this nerve virtually inevitable. However, significant sensory dysfunction of the LBN is extremely rare (see Treatment).