Proper training must prepare responders to consider various hazards and means by which to mitigate their effects. This article describes one such training program (the National Disaster Life Support program) as a possible means to prepare dental providers to better respond to disasters and describes a simple triage technique that can be used by dental professionals to triage patients.

Human nature is inclined to respond to disasters by whatever means available, and dental professionals are no different. Historically, hundreds of volunteers have turned out to assist in response to floods, earthquakes, hurricanes, explosions, and disasters of every conceivable type. The motivation is generally one of compassion for our fellow humans and a sincere desire to help. In recent years it has been recognized that response of untrained volunteers can be counterproductive and can lead to serious risks to the multitude of responders. The role of dental health professionals during a disaster has historically been ill defined. The role of dental health professionals in identifying remains of victims is well documented in diverse multiple incidents from plane crashes to mass graves . A training program in Australia focuses on better preparing dental professionals to perform dental autopsy for this vital function .

Displaced persons from natural disasters need emergency and routine dental care. Relegating dental professionals to these two roles only during disasters would be short sighted, imprudent, and illogical. Dental professionals are, first and foremost, health care providers with knowledge of anatomy, physiology, medication administration, and emergency interventions. With proper training, dental providers can become a force multiplier for other emergency responders to disasters of various types. Some states already have enacted laws that expand the dental provider’s scope of practice during a disaster .

The importance of proper training cannot be understated. We must recognize that the first responders to a disaster scene, despite their noble intent, are unaware of the precise cause of the event and, more importantly, are unaware of the possible secondary consequences of the event. It may be apparent that an explosion has occurred, but was it accidental or intentional? Did it result in the dispersion of dangerous chemicals into the scene? Are biologic or radioactive agents contaminating the area? Is there a likelihood of secondary explosions that could jeopardize the responders’ safety? Are there structural or environmental threats as a result of the event? These are among the many reasons why dental professionals and all first responders should approach a disaster scene with a careful and systematic approach—an all-hazards approach. The alternative risk is that they may become secondary victims of the event, thereby increasing the number of victims and reducing the number of effective responders. Proper training must prepare responders to consider various hazards and means by which to mitigate their effects. This article describes one such training program (the National Disaster Life Support [NDLS] program) as a possible means to prepare dental providers to better respond to disasters and describes a simple triage technique that can be used by dental professionals to triage patients.

A commonality of approach to disasters is vital to an effective response . A community can have the best trained fire personnel, the most competent and well-trained paramedics, and the best trained police imaginable, but if they are not trained in a manner that facilitates working cohesively, their disparate training can result in less-than-optimal effectiveness—it can be counterproductive.

Recognizing the need for a common approach, a group of personnel from four academic institutions—the Medical College of Georgia, the University of Georgia, the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, and the University of Texas School of Public Health–Houston—partnered in an effort to develop a standardized all-hazards curriculum for the training of responder personnel. Congressional funding was sought for support of the developmental effort, and Senator Max Cleland (D-GA) proposed the initiative on the floor of the US Senate on September 10, 2001 . The events of the next day underscored the importance of the proposed effort. Funding was made available through the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, and subsequently a partnership with the American Medical Association and American College of Emergency Physicians was formed.

The result was a family of courses, called the NDLS courses, to provide awareness level to operations level training to a multidisciplinary spectrum of providers from first responders to advanced in-hospital care. These courses, Core Disaster Life Support (CDLS), Basic Disaster Life Support (BDLS), Advanced Disaster Life Support (ADLS), and NDLS decontamination, are designed to create interoperable providers across the spectrum of personnel, and dental professionals are no exception.

The CDLS course is a 4-hour awareness level course directed at nonmedical personnel. The course lays the foundation on which the entire family of NDLS courses is based. This foundation consists of several unique memory mnemonics that serve to facilitate recall of key response components otherwise easily overlooked under the stress of emergency response.

The BDLS course is the introductory course for medical personnel, including emergency medical technicians, paramedics, nurses, physicians, dentists, veterinarians, and other health care providers. The content is based on the DISASTER paradigm for each of the topics, including triage, natural disasters, traumatic and explosive events, chemical events, biologic events, nuclear/radiation events, and psychological consequences. Additional topics provide a well-rounded opportunity for understanding the complex aspects of disaster consequences.

The ADLS course is a 2-day practical, hands-on, training program that covers the practical aspects of rendering aid to the unique kinds of injuries to be found at a disaster scene. The topics covered include patient treatment procedures, mass prophylaxis, patient decontamination, mass triage, and associated skills.

The fourth course is NDLS-decontamination. This course provides operational level training in the procedures of patient decontamination. It addresses the fact that typically to reserve medical personnel for care delivery, a hospital staffs a decontamination team with nonmedical individuals. This team can include personnel from public safety, maintenance, and housekeeping. It is imperative that these teams understand the policies and procedures of decontamination and have an opportunity to actually conduct practice on mock victims.

All of the NDLS courses are organized around a unifying mnemonic called the DISASTER paradigm:

-

D: Detect

-

I: Incident command

-

S: Safety and security

-

A: Assess hazards

-

S: Support

-

T: Triage and treatment

-

E: Evacuation

-

R: Recovery

Each topic addressed in each course is structured around this unifying theme.

One of the most vital functions that a dental health provider can provide during a disaster is triage, or the sorting of victims into priorities of treatment. Controversy exists over the manner and method of the triage of disaster victims. The NDLS courses teach a simple type of triage called MASS triage:

-

M: Move

-

A: Assess

-

S: Sort

-

S: Send

MASS triage is based on the fact that the gross motor component of the Glasgow Coma Scale and systolic blood pressure is a good predictor of mortality from trauma . “Id-me” Is an easy-to-remember phrase that incorporates a mnemonic device for sorting patients during mass casualty incident (MCI) triage into I mmediate, D elayed, M inimal, and E xpectant.

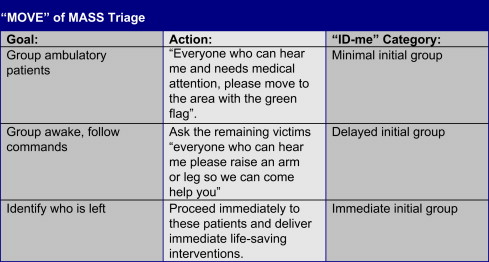

Mass triage “MOVE”

The initial challenge in triage is to determine accurately which patients need immediate lifesaving care versus which patients are simply demanding immediate attention. Victims screaming and calling for help, scene confusion, victims wandering around the area, and a multitude of other distractions can limit your effectiveness. The first step in triaging a large group of patients is to ask them to move. For example, if a large group of patients is congregated, one might shout, “Everyone who can hear me and needs medical attention, please move to the area with the green flag.” Believing that they will receive medical care more quickly, the ambulatory patients likely will move to the designated area. Patients who are able to ambulate should, by virtue of this fact, have an intact airway, breathing, circulation, and blood pressure adequate enough to sustain an ambulatory position. This group of patients who is able to ambulate to another location should be considered “minimal” for a triage group category during this initial triage step. Because this initial step groups patients without individual assessment of each patient, some individuals may have conditions that worsen and result in a more urgent triage category.

The second step of the “MOVE” of MASS triage is to ask the remaining victims to move an arm or leg. For example, say to the remaining victims, “Everyone who can hear me, please raise an arm or leg so we can come help you.” To follow this command, the victim must have sufficient vital signs for them to remain conscious, hear the instructions, and follow commands but be unable to ambulate because of injury or other serious conditions. This patient group is considered the initial delayed group for a triage category ( Fig. 1 ).