Although distraction osteogenesis (DO) of the midface in theory is no different from DO performed at other sites, the surgical application of DO in the midfacial region is different. As discussed in the article by Jensen and Block elsewhere in this issue, DO is a biologic process that promotes bone formation between the cut surfaces of bone segments that is initiated when traction is applied to separate the bony segments. This process also initiates histiogenesis of the tissues surrounding the distracted bone: cartilage, ligaments, muscle, blood vessels, gingival, and nerve tissue.

DO as it applies to the midface is not a new concept. According to Balaji, Fauchard described the use of an expansion arch as early as 1728, applying it to widen the arches to a more physiologic form. Wescott attempted to correct a crossbite by placing two double clasps on the maxillary bicuspid teeth and a telescopic bar to apply transverse force and Angell expanded a maxillary arch by using a transverse jackscrew and clasps on the bicuspid teeth. Goddard is credited with standardization of the palatal expansion protocol with activation twice daily for 3 weeks followed by a period of stabilization.

Codivilla is credited with using an external skeletal traction apparatus after performing an oblique femoral osteotomy to accomplish the first lower extremity lengthening. Although Gavril Ilizarov was the first to describe a tissue-sparing osteotomy and a reliable distraction protocol that involved the long bones of the lower extremity in 1951, modern clinical DO of the facial bones developed once McCarthy and colleagues applied the concept to mandibular lengthening in 1992. This led to an explosion of clinical and research activity in craniomaxillofacial DO over the past decade. As in other sites, midfacial DO involves five distinct periods: osteotomy, latency, distraction, consolidation, and remodeling.

Adapting distraction osteogenesis from tubular long bones to irregularly shaped membranous bones

DO can be applied to multiple sites in the midfacial skeleton in pediatric and adult populations. The application of the concepts described in limb lengthening and the distraction of tubular long (endochondral) bones, however, must be modified when applied to the irregularly shaped membranous bones of the midfacial skeleton. There are several anatomic sites in the midfacial skeleton where DO may have an application. These include the maxilla at the Le Fort I, II, and III levels; the nasal and zygomatic bones; and the bones of the cranium. In addition, DO can be applied to healed bone grafts in the craniomaxiofacial skeleton and to vertical and horizontal defects of the maxillary alveolus (see the article by Spagnoli elsewhere in this issue).

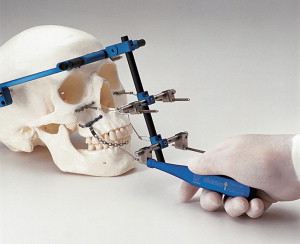

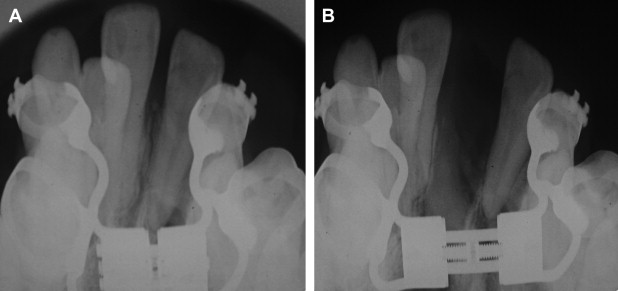

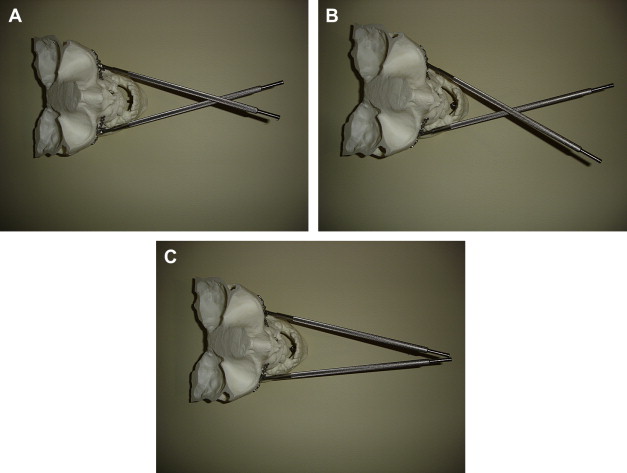

As discussed in the article by Reddy and Elhadi elsewhere in this issue, the hardware required for distraction of each region may vary as much as the distraction protocols differ from themselves ( Box 1 ). Hardware may range from large external halo-like devices ( Fig. 1 ) to jackscrews that attach to the teeth ( Fig. 2 ). The goals of treatment and the ideal vectors used in each of these regions also are distinct. Certain devices allow distraction in more than one plane or direction (see Fig. 1 ). At times two devices may be used simultaneously; however, neither the devices nor their vectors of distraction should be allowed to interfere with each other ( Fig. 3 ).

External—bone-borne

Internal—subcutaneous

-

Intraoral

- •

Extramucosal

- •

Tooth-borne

- •

Dental implant-borne

- •

- •

Submucosal

- •

Bone-borne

- •

Hybrid

- •

- •

-

Classification according to distraction direction

- •

Unidirectional

- •

Bidirectional

- •

Multidirectional

-

Classification according to site of midfacial distraction

- •

Le Fort I, II, III

- •

Nasal bones

- •

Zygomatic bones

- •

Healed bone grafts

- •

Maxillary alveolus

- •

Transverse

- •

Vertical

- •

Horizontal

- •

Data from Sándor GKB, Ylikontiola LP, Serlo W, et al. Midfacial distraction osteogenesis. Oral Maxillofacial Surg Clin North America 2005;17(4):485–501.

Indications

Midfacial DO is labor intensive and technique sensitive as a treatment modality and should be reserved for specific indications. Midfacial DO has two main advantages over traditional osteotomies of the midface. First, DO can produce larger movements than traditional osteotomies. Second, DO seems to be associated with less relapse than traditional osteotomies. DO, therefore, should be reserved for significant bony movements in the treatment of conditions known to have high relapse rates after traditional osteotomies.

DO can be repeated during different phases of life. In some cases, the application of a halo to the skull and a few simple titanium plates screwed into the bones of the craniomaxillofacial skeleton may be less invasive than certain osteotomies of the midface. Moreover, developing tooth roots of the maxilla can be avoided and left undamaged by the design of osteotomies used in DO of the midface.

Cleft lip and palate patients often require significant advancement of their midface at one or more Le Fort levels. Maxillary advancement using traditional osteotomies may place these patients at risk for the development of velopharyngeal insufficiency. It has been reported that this debilitating complication may be avoided for some of these patients if DO is used to advance the maxilla perhaps because it leaves the posterior dentition and velopharyngeal relationships undisturbed.

DO of the midface also may be applied in situations requiring emergent care. It can ameliorate obstructive sleep apnea in Crouzon’s syndrome, for example, possibly avoiding the need for tracheostomy. DO also is used to provide urgent ocular protection in Pfeiffer’s syndrome.

Indications

Midfacial DO is labor intensive and technique sensitive as a treatment modality and should be reserved for specific indications. Midfacial DO has two main advantages over traditional osteotomies of the midface. First, DO can produce larger movements than traditional osteotomies. Second, DO seems to be associated with less relapse than traditional osteotomies. DO, therefore, should be reserved for significant bony movements in the treatment of conditions known to have high relapse rates after traditional osteotomies.

DO can be repeated during different phases of life. In some cases, the application of a halo to the skull and a few simple titanium plates screwed into the bones of the craniomaxillofacial skeleton may be less invasive than certain osteotomies of the midface. Moreover, developing tooth roots of the maxilla can be avoided and left undamaged by the design of osteotomies used in DO of the midface.

Cleft lip and palate patients often require significant advancement of their midface at one or more Le Fort levels. Maxillary advancement using traditional osteotomies may place these patients at risk for the development of velopharyngeal insufficiency. It has been reported that this debilitating complication may be avoided for some of these patients if DO is used to advance the maxilla perhaps because it leaves the posterior dentition and velopharyngeal relationships undisturbed.

DO of the midface also may be applied in situations requiring emergent care. It can ameliorate obstructive sleep apnea in Crouzon’s syndrome, for example, possibly avoiding the need for tracheostomy. DO also is used to provide urgent ocular protection in Pfeiffer’s syndrome.

Distraction osteogenesis in cleft lip and palate

DO offers several advantages over conventional osteotomies in the treatment of cleft lip and palate patients. There is a reduced tendency for significant relapse after distraction of the maxilla than after traditional maxillary osteotomies. The soft tissue changes associated with maxillary advancement may be superior after DO when compared with traditional Le Fort I level advancement surgery. It also is possible that deterioration of velophayngeal function may be avoided in patients at risk for the development of velopharyngeal insufficiency.

The midfacial deformities seen in cleft lip and palate patients include transverse maxillary deficiency, midfacial retrusion, and significant alveolar cleft defects. Transverse maxillary deficiency in unilateral cleft lip and palate patients can be corrected with corticotomy and distraction in a modified procedure similar to the surgically assisted rapid palatal expansion procedure in which distraction is performed across the midpalatal suture. Despite the presence of a palatal cleft, transverse deficiency of the unilateral cleft maxilla can be corrected reliably using DO (see Fig. 2 ). It is the opinion of the authors that transverse discrepancy should be corrected first, before anteroposterior discrepancies are treated with DO.

Midfacial retrusion may be treated at the Le Fort I, II, or III levels. Le Fort I level distraction may involve advancement of segmentalized maxillary fragments or of the entire maxilla. Experimental advancement of anterior maxillary segments osteotomized at the Le Fort I level in sheep and in primates has been shown to be followed by bone healing typical of DO.

Distraction hardware developed for anterior maxillary segmental advancement ( Figs. 4 and 5 ) has been used successfully in patients who have cleft lip and palate. A stereolithic skull reconstructed from a 3-D CT scan can aid planning of such osteotomies by permitting preoperative selection and bending of plates, thus reducing expenditures on distraction hardware and operating room time ( Figs. 6 and 7 ). Preoperative planning also ensures that a certain configuration and arrangement of the selected distraction hardware actually produce the vectors of distraction desired ( Figs. 8–10 ).