Chapter 5

Medicine: Specialized Suites

The American Board of Medical Specialties recognizes, as of this writing, 24 medical specialties and over 100 subspecialties. The specialties are Allergy and Immunology, Anesthesiology, Colon and Rectal Surgery, Dermatology, Family Medicine, Internal Medicine, Neurological Surgery, Nuclear Medicine, Obstetrics and Gynecology, Ophthalmology, Orthopedic Surgery, Otolaryngology, Pathology, Pediatrics, Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, Plastic Surgery, Preventive Medicine, Psychiatry and Neurology, Radiology, Surgery, Thoracic Surgery, Urology, Emergency Medicine, and Medical Genetics.

Subspecialties under Internal Medicine are Cardiovascular Disease, Endocrinology, Diabetes and Metabolism, Gastroenterology, Hematology, Infectious Disease, Medical Oncology, Nephrology, Pulmonary Disease, Rheumatology, Adolescent Medicine, Clinical Cardiac Electrophysiology, Critical Care Medicine, Geriatric Medicine, and Sports Medicine. Subspecialties under Pediatrics are Pediatric Cardiology, Pediatric Gastroenterology, Pediatric Endocrinology, Pediatric Hematology-Oncology Neonatal-Perinatal Medicine, Nephrology, Pediatric Critical Care Medicine, Pediatric Emergency Medicine, Pediatric Infectious Diseases, Pediatric Rheumatology, Sports Medicine, Sleep Medicine, Medical Toxicology, and Adolescent Medicine. There are a few other subspecialties under Psychiatry and Neurology, such as Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, Pain Medicine, and Sleep Medicine.

Although Family Medicine, Pediatrics, and Internal Medicine are primary medical practices, they are also listed as specialties by the American Board of Medical Specialties, since physicians in these specialties must take and pass specialty boards that certify their competence in their respective fields. Those in these three “specialties,” then, are primary-practice physicians, whereas many of the other specialties listed above tend to be referral specialties—patients are referred by their primary care physicians.

This chapter will discuss the requirements of the medical specialties the designer or architect is most likely to encounter in a medical office building. It is assumed that the reader will have read Chapter 3, which is the foundation for Chapter 5.

As a general comment, the same economic pressures and regulatory issues that have affected primary care physicians have impacted specialty care except for a few specialties like reproductive medicine/IVF, dermatology (especially practices focused on cosmetic procedures), and plastic surgery, which are for the most part paid out of pocket by the patient. In recent years, physicians have wanted to do as many tests as possible in their offices to capture the additional revenue. Today, in many parts of the United States, reimbursement is so low that the more procedures one does, the more one loses. Medicare is the largest payer in the United States, and what it will or will not cover and the amount it pays influences other payers as well as the types of procedures physicians are willing to do in their offices. If it’s not reimbursed, the patient may be referred to the local hospital for the procedure. This is especially true if the investment in equipment is large and the regulatory documentation for the procedure is burdensome; if the reimbursement is low, physicians are likely to refer patients elsewhere.

SURGICAL SPECIALTIES

To avoid redundancy, certain issues common to all surgical specialties with respect to minor surgery rooms and office-based outpatient surgery suites will be discussed here, rather than under each specialty heading. However, the Plastic Surgery section has the most complete discussion of office-based surgery (OBS) suites in terms of layout and design issues. The three levels of surgery discussed below are designated by the American College of Surgeons (ACS) as Classes A, B, or C (www.fasc.org) and Levels I, II, or III in the State of Kentucky “model” document on the ACS website (www.facs.org/ahp/kyOBSguide12.03.pdf). The wording is different in each of these documents but similar in content. The document from the state of Kentucky is referenced here because it provides explanatory background that may be interesting to some readers and it came up numerous times in the author’s research on this topic. States will vary in their approaches to regulating OBS and the design professional needs to be familiar with the jurisdiction in which they are working. A physician’s authority to perform procedures in an office is established by that practitioner’s license to practice his or her profession, and it is expected that this will be carried out according to current standards of care but documentation of those standards may or may not exist in a specific state. When a practitioner seeks Medicare certification or accreditation by one of three national agencies, it imposes a level of patient safety and regulation. This will be discussed in detail under the Plastic Surgery specialty. The reader is also referred to the well-established Guidelines for Design and Construction of Health Care Facilities (2010), published by the Facility Guidelines Institute, Section 3.8: “Specific Requirements for Office Surgical Facilities.”

Office Surgery/ACS Class A

Physicians with specialties in OB-GYN, otolaryngology (ENT), ophthalmology, dermatology, plastic surgery, general surgery, urology, and occasionally, orthopedic surgery, will have a minor surgery or special procedures room where they may use local or topical anesthetics not involving drug-induced alteration of consciousness and this requires no special accommodation other than generally accepted standards of care, resuscitation equipment (in some jurisdictions), and staff trained to respond to patient safety emergencies. Chances of complications are remote.

Office Surgery/ACS Class B

Level II procedures may require the use of minimal to moderate intravenous or intramuscular sedation making postoperative monitoring necessary. Endoscopy procedures, for example, are often done with conscious sedation, which involves intravenous (IV) sedatives like Valium® often combined with an agent that acts like an amnesiac so that the memory of pain is erased. When conscious sedation is administered, monitoring equipment and a resuscitation cart are required. Urologists now infrequently use this type of sedation when performing cystoscopies, as many physicians are reluctant to assume the liability and risks of using conscious sedation in their offices unless they do many procedures that require it and have properly trained staff to monitor patients. As an option, a surgeon may contract with an anesthesia service to assist in a procedure. An anesthesiologist or nurse anesthetist with a portable anesthesia machine will come to the surgeon’s office as scheduled.

The American College of Surgeons defines Class B as “provides for minor or major surgical procedures in conjunction with oral, parenteral, or intravenous sedation or under analgesic or dissociative drugs.”

Office Surgery/ACS Class C

Procedures requiring deep sedation, general anesthesia, or major nerve block and in which the known complications have the potential to be serious and/or life-threatening, and for which support of vital bodily functions is necessary.

Office-Based Surgery

The American College of Surgeons defines office-based surgery (OBS) as “any surgical facility organized in or for the surgeon’s office for the purpose of providing invasive surgical care to patients with the expectation that they will be recovered sufficiently to be discharged within a reasonable amount of time” (www.facs.org).

Plastic surgeons are the most likely physicians to have an office-based surgery center within their suites, followed by dermatologists and, occasionally, otolaryngologists. Pain management specialists, such as physiatrists and anesthesiologists, do interventional procedures that are considered office-based surgery, and gastroenterologists perform a number of endoscopic procedures, usually in an endoscopy center designed to office-based surgery center standards. As statutes and codes vary widely from state to state, the following comments reflect national trends driven by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) for facility certification or the Accreditation Association for Ambulatory Health Care (AAAHC) accreditation. See also Chapters 8 and 14 for more in-depth discussion of regulations and codes.

As a prelude, it should be noted that physicians setting up office-based surgery suites have historically had considerable flexibility in the layout of these facilities, generally trying to fit two pounds of program into a one-pound container. Operating room sizes, space around each recovery bed, and ancillary rooms (clean and soiled utilities, scrub area, staff and patient dressing areas) have been left largely to the discretion of the physician, sometimes resulting in “funky” layouts. One may find a “prep room” in which clean and soiled utilities are accommodated side by side, rather than in separate rooms. Minimum-width corridors and clearances may also have been compromised. Unless physicians seek Medicare certification in order to be able to bill a fee for the use of the facility (in addition to the surgeon’s fees), they may be able to avert close scrutiny on these issues, although professional societies such as the American Society of Plastic and Reconstructive Surgeons have spoken out boldly about the risks to patients in facilities that have not been designed to meet minimum standards required by accreditation agencies (Iverson 2002)1. As of this writing, 27 states have regulations and standards for office-based surgery settings (Mowles 2012)2 often incorporating guidelines developed by the American College of Surgeons (ASC) (www.facs.org/commerce/guidelines.html). [A “free” copy of the document Guidelines for Optimal Ambulatory Surgical Care and Office-based Surgery, Third edition, 2000, may be accessed from the website of the American Urological Association (www.auanet.org/resources/office-based-surgery/office-based-surgery.cfm).] For the past decade, surgery performed in office-based settings has attracted the attention of state legislators and regulators throughout the nation. Individual professional societies, however, may not always embrace the notion of what they view as overly burdensome requirements, as evidenced by this letter from the American Society of Dermatologic Surgery Association to a policy analyst at the Oregon Medical Board on the occasion of Oregon’s move toward mandatory accreditation for minimally invasive outpatient surgery (Flynn 2013).3

The Joint Commission stepped up to the plate with its Office-Based Surgery (OBS) Standards, approved 2001, intended for physicians and dentists performing operative and invasive procedures in an office setting. To be eligible for accreditation under the OBS standards, a provider must meet all of the following criteria:

- The practice comprises four or fewer licensed surgeons performing operative or invasive procedures.

- The organization or practice must be surgeon-owned or operated such as a professional services corporation, private physician practice, or small group practice.

- Invasive surgical services are provided to patients and local anesthesia, minimal sedation, conscious sedation, or general anesthesia is administered. Laser eye surgery and dermatological procedures using topical anesthesia qualify.

- OBS practices that render four or more patients incapable of self-preservation at the same time are required to meet the provisions of the Life Safety Code, NFPA 101, of the National Fire Protection Association (NFPA).

Office-based surgery suites often fall into a “gray area” in terms of codes. For example, the Uniform Building Code (UBC) classifies them as a “B,” or office occupancy, if fewer than five individuals are incapable of self-preservation, which limits the enterprise to two ORs and three recovery beds or one OR and four recovery beds. (NFPA 101 limits it to four persons or fewer.) The local department of public health will, in many jurisdictions, send an inspector to review life safety issues, and this individual may demand accommodations that go beyond what is stipulated in the local building code and in NFPA 101® Life Safety® Code.

An example might be that the surgery portion of the suite be separate from the physician’s office practice with a dedicated entry and reception office. This seems unwarranted in a one-physician practice in which the doctor can only be in one place or the other. However, from the standpoint of patient safety, in theory, nothing would preclude the physician from allowing an “outside” physician to see patients while he or she is performing surgery, and the front office staff might be distracted when called upon to assist in an emergency to evacuate a patient. Nevertheless, this results in the need for additional staff and additional space, which might exceed the physician’s budget.

A good place for a design professional to start is to reference the Guidelines for Design and Construction of Health Care Facilities (2010), Section 3.8, for requirements for office surgical facilities.

Physicians will want to be accredited by one of a number of possible agencies that vary, in terms of physical design considerations, from flexible to rigorous. See the Plastic Surgery section for more detail.

To reflect the range of options the architect or designer may encounter, the suite plans in this book demonstrate both types of office-based surgery suites—those that meet physicians’ functional needs but may be somewhat idiosyncratic in layout, and those meeting more rigorous standards, which is where things are headed.

OBSTETRICS AND GYNECOLOGY

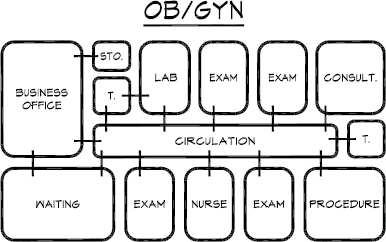

This is a high-volume practice, so patient flow must be carefully analyzed. Obstetrical patients usually make monthly visits, which entail weighing and a brief examination. Gynecology patients require a more lengthy pelvic examination. This type of practice requires a large staff, as each physician needs one or two nurses; often, two physicians share three nurses or aides in addition to the front office staff. It is customary for a female nurse to be present during pelvic examinations, necessitating more staff per doctor than required with many other medical specialties. Figure 5-1 shows the relationship of rooms.

Figure 5-1. Schematic diagram of OB/GYN suite.

Nurse Practitioner

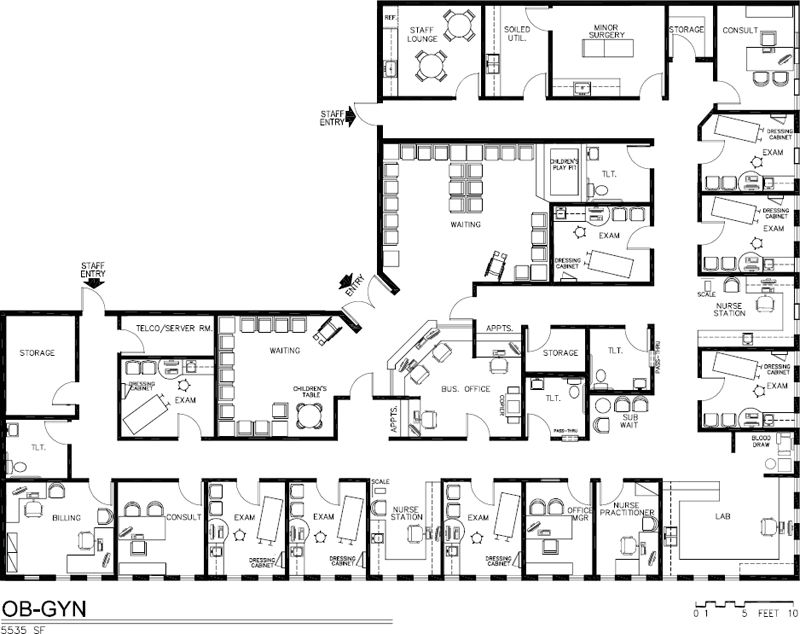

A trend in this field is the use of nurse practitioners and midwives to perform routine patient examinations. A registered nurse (R.N.) with additional training in OB-GYN can be certified to work in this capacity (refer to Chapter 3 for more detail). This frees physicians from routine pelvic examinations and Pap smears on healthy patients, allowing them to concentrate on diagnosis of disease. Offices using nurse practitioners will need larger nurse stations or perhaps a small private office for them (Figure 5-2).

Figure 5-2. Space plan for OB/GYN suite, 5,535 square feet.

Patient Flow

There probably would not be more than three doctors working in an office at one time, even if it were a four- or five-person practice, since one or two doctors may be delivering babies, making hospital rounds, or taking the day off. There should be three to four exam rooms per physician. The patient flow is from waiting room to weighing area, to toilet (urine specimen), to exam room. A good space plan will channel patients to each area by the most direct route with no backtracking or unnecessary steps. If possible, the nurse station/sterilization/lab areas should be located toward the front of the suite (centralized) so that the staff can cover for each other, and duplication of personnel is avoided.

Waiting Room

The waiting room of an OB-GYN suite should be large and comfortable. Unexpected deliveries frequently make the doctor late and necessitate a long wait for patients. The patient is apt to be more forgiving if her wait is in a well-designed room with good lighting, current magazines, comfortable seating, and interesting artwork on the walls. A play area for children would be a practical addition to the waiting room, since many patients are young mothers who are apt to bring their children with them.

Table 5-1. Analysis of Program Obstetrics and Gynecology

| No. of Physicians | 1 | 2 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Exam Rooms | 3@ | 10 × 12 = 360 | 7 @ | 10 × 12 = 720 |

| Exam/Ultrasound | 10 × 12 = 120 | 2 @ | 10 × 12 = 240 | |

| Consultation Room/Private office | 10 × 12 = 120 | 2 @ | 10 × 12 = 240 | |

| Nurse Stationa | 10 × 10 = 100 | 2 @ | 10 × 10 = 200 | |

| Laboratory | — | 8 × 10 = 80 | ||

| Toilets | 2@ | 8 × 8 = 128 | 3 @ | 8 × 8 = 192 |

| Minor Surgery | 12 × 14 = 168 | 12 × 14 = 168 | ||

| Equipment or Soiled Utility | 60 SF | 60 SF | ||

| Staff Lounge | 10 × 12 = 120 | 12 × 12 = 144 | ||

| Storage | 6 × 8 = 48 | 6 × 8 = 48 | ||

| Nurse Practitioner | — | 8 × 10 = 80 | ||

| Business Officeb | 16 × 18 = 228 | 16 × 18 = 228 | ||

| Office Manager | 8 × 10 = 80 | |||

| Surgery Scheduling | 8 × 10 = 80 | 8 × 10 = 80 | ||

| Waiting Room | 14 × 20 = 280 | 20 × 25 = 500 | ||

| Tel. Equip./Server Closet | 4 × 5 = 20 | 4 × 5 = 20 | ||

| Biohazard | 4 × 4 = 16 | 4 × 4 = 16 | ||

| Subtotal | 1,848 SF | 3,096 SF | ||

| 20% Circulation | 369 | 619 | ||

| Total | 2,217 SF | 3715 SF | ||

| aCombined with lab. | ||||

| bIncludes reception, appointments, bookkeeping, and insurance/collections. | ||||

| Note: The nurse practitioner counts as another provider. | ||||

Exam Rooms

Exam rooms may have painted walls or vinyl wallcovering, perhaps a wood-look vinyl floor, and a dressing area where patients may disrobe in privacy and hang underwear out of sight. Upon dressing, they may check makeup and hair in a mirror before leaving the exam room. This dressing area can be a 3 × 3–foot corner of a room with a ceiling-mounted cubicle drape and a chair or built-in bench. Or, it can be a hinged space-saver panel that opens perpendicular to the wall (see Figure 3-51). Remember that the door to the exam room must open to shield the patient.

The size of an OB-GYN exam room may be 8 × 12 feet but this width is tight, especially if the casework has an area for a monitor and a place for the patient and physician to sit side by side to view the monitor. A room 10 × 12 feet is desirable and allows the physician to remain in the room while the patient dresses behind a curtain in order to chart and write a prescription as depicted in Figure 5-3. Allow space for a printer in the nurse station to print the prescription and other notes to be handed to the patient upon exit.

Figure 5-3. Space plan of OB/GYN suite, 1,900 square feet.

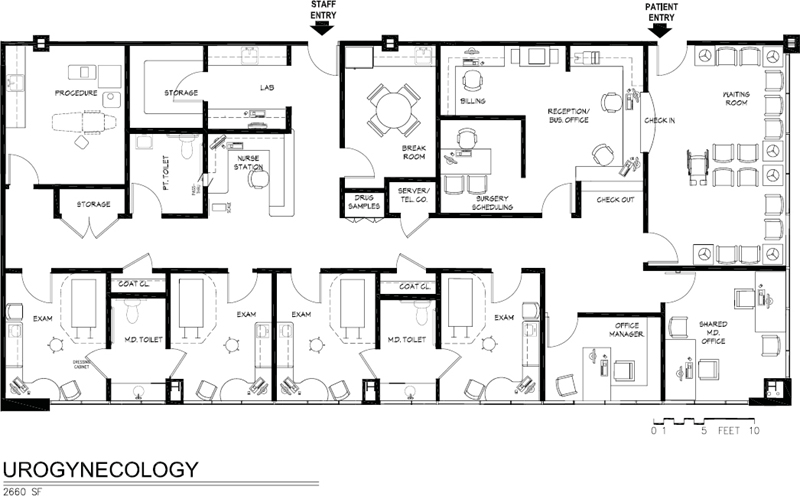

The orientation of the room should allow the physician to be on the patient’s right side although most of the activity occurs at the end of the table. In Figure 5-4 because two exam rooms share a bathroom, the orientation is mirror-image due to having achieved a higher goal of immediate access to a bathroom.

Figure 5-4. Space plan urogynecology suite, 2,660 square feet.

The position of the sink cabinet is particularly important in an OB-GYN exam room because many items are dropped into it during the procedure. Not much countertop space is needed except for a sit-down workstation to be able to enter data. The physician should be able to examine the patient with the right hand and reach for instruments from the cabinet or Mayo stand with the left hand (see Figure 5-3). The sink should be positioned close to the end of the exam table. The type of exam table used here is a pelvic table with stirrups. Such tables often have a built-in speculum warmer. Alternatively, one drawer of the sink cabinet may have an electrical outlet at the rear for warming instruments. However, the increasing use of disposable specula will soon make this a nonissue. Three electrical outlets are required: One must be located near the foot of the table for the examination lamp used for pelvic exams; one should be located above the sink countertop; and the third should be located on the long wall, near the head of the table. There is no need for wall-mounted diagnostic instruments in this medical specialty.

It is pleasant to have windows in an OB-GYN exam room. The wait is frequently long and being able to look outside makes the wait a little more pleasant. Vertical blinds or mesh shades serve exam rooms well since they permit light and view to enter the room while protecting the occupant’s privacy.

Minor Surgery/Special Procedures

OB-GYN suites will have a minor surgery room where a variety of procedures are performed (see Figures 5-2 and 5-3). See also Figure 3-5, although it is not specifically set up for OB-GYN, the accompanying text addresses it. The plan in Figure 5-3 shows a procedure room with an equipment storage room opening off of it. The sink should be a large one with foot pedal control that can be used as a scrub sink. Special procedure rooms such as this always have a sink in them; however, it should be noted that operating rooms such as may be found in plastic surgery or dermatology suites would not have a sink, as regulatory agencies would view this as a breach of infection control. Sinks and drains are considered a potential source of pathogens.

Types of Procedures

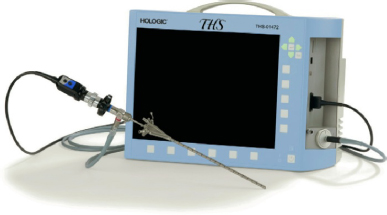

The kinds of procedures that may be performed in this room include (if the gynecologist has a subspecialty in urology) cystoscopies, hysteroscopies (examination of the uterus with a fiber-optic scope), D&Cs, colposcopies (examination of the cervix with magnification), and LEEP (loop electrosurgical excision procedure), which replaces core biopsies. The colposcope (Figure 5-5a) and all other equipment are portable. A version of this equipment is available with video and direct upload to an EHR. The LEEP equipment generates smoke, requiring a smoke evacuation machine (Figure 5-5b) that can be stored in the equipment room. Colposcopy and LEEP can also be performed in a standard exam room. Sedation is not required, which negates the need for a recovery area. Suction (may be central or portable) is required in this room, but other medical gases are not. The room may have a video monitor associated with the colposcope or other fiber-optic scopes, in which case glare on the screen from windows or light fixtures may be a problem. The video monitor enables the patient to view the procedure and, with a printer, an image can be captured as a still photo for future reference. With a telemedicine connection, video images can be viewed at remote locations. Lighting in this room should be able to be dimmed if video monitors are used. The Hologic THS® hysteroscopy system (Figure 5-6) also uses a fiber-optic scope.

Figure 5-5a. Colposcope is used for examining the cervix with magnification. This example is manufactured by Leisegang Optik™.

Figure 5-5b. Laser smoke evacuation machine, a product of Laservac 750™.

Figure 5-6. THS® tower-free hysteroscope system used to examine the uterus with a fiber-optic scope.

Note that fiber-optic scopes need to be disinfected after use. A specific cleaning process is followed. In many practices this will be done manually, first washing the scopes in a sink and later soaking them in a strong chemical solution in tubs that sit on the counter. Refer to Chapter 3, Endoscopy, and to Urology in this chapter for further discussion.

Room Size

The size of the room may vary from 12 × 14 feet to 14 × 16 feet, depending on the number of assistants who must be in the room and the amount of medical equipment. Usually, an adjustable-height standard procedure table, as in Figure 3-61 would be used, however, a gynecologist with a specialty in urology—a urogynecologist—would use a urodynamics procedure chair in this room.

Ultrasound

A common piece of equipment in an OB-GYN office is an ultrasound machine, which is used to observe the developing fetus and also to image growths such as fibroids and cysts. It requires a trained sonographer. The room should be located close to a bathroom, as women are usually asked to drink a large quantity of water prior to the procedure and, immediately after, will need to void. Although this equipment is portable, it is large (Figures 5-7 and 5-8) and awkward to move from room to room. It is usually placed in a large (10 × 12–foot) exam room that can also be used for standard examinations (Figures 5-9 and 5-10). Small ultrasound units are becoming increasingly popular and can be tucked into a corner of a small exam room or, in the case of the SonoSite (see Figure 3-84) can be carried from room to room. Smaller machines may not offer the detail provided by the larger machines but that is a clinical decision. Ultrasound rooms need dimmable lighting. Two guest chairs should be provided for family members who want to “experience” the heartbeat of the fetus. An ultrasound room should have lighting that can be dimmed.

Figure 5-7. Ultrasound machine, Acuson SC2000.

Figure 5-8. Fetal monitoring with ultrasound.

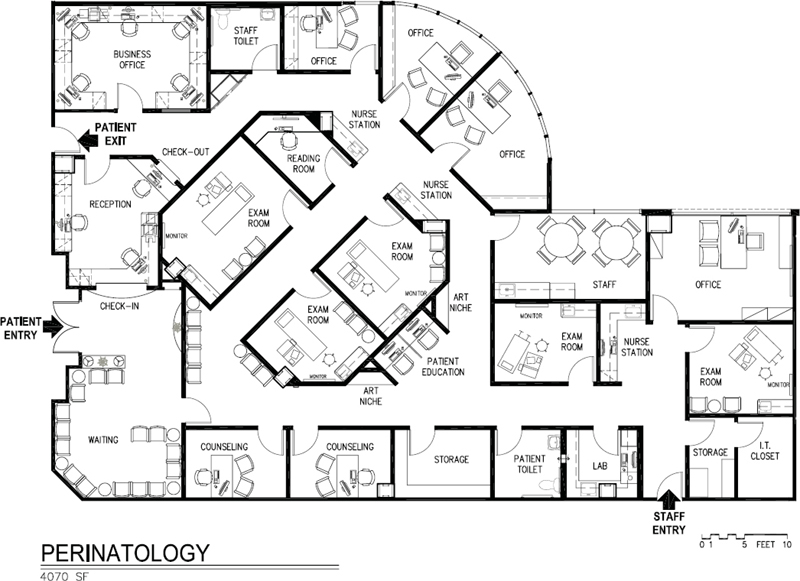

Figure 5-9. Space plan for perinatology suite, 4,070 square feet.

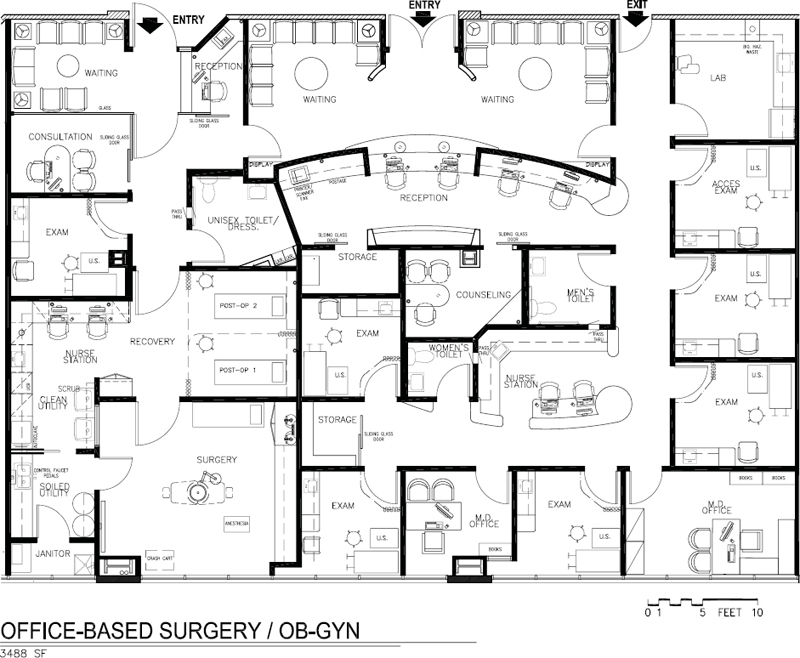

Figure 5-10. Space plan for office-based surgery and OB-GYN, 3,488 square feet.

OB/GYN and Office-Based Surgery Center

The office in Figure 5-10 functions as a primary care provider to women with a focus on OB/GYN. The practitioners are OB/GYN physicians whose goal is to provide total care to their patients, many of whom are executives and others associated with the film industry due to the office’s proximity to the film studios. An accredited, licensed office-based surgery center is made available to other physicians in the MOB and also serves this medical practice. Each exam room has a large ultrasound machine.

Patient Education

Many printed educational pamphlets are distributed, so suitable storage racks should be provided in the waiting room or in the corridor near the nurse station. (Despite the availability of online reference material and educational websites, printed brochures still exist.)

Disposal of Infectious Waste

A large amount of trash is generated in this practice. A disposable gown, sheet, and exam table paper must be discarded after each patient, as well as paper hand towels and other disposable items. Each exam room should have a large trash receptacle, which may be built into the cabinet or freestanding.

It should be noted that many cities, as well as OSHA, have regulations for dealing with infectious waste. These used to apply only to hospitals, but with the presence of HIV and other “super” viruses, medical offices are also required to separate their trash (refer to Chapter 3, OSHA Issues). Provision has to be made in the examination room for two receptacles. Paper from the exam table, paper towels, and wrappings from disposables could go into one container, and items coming into contact with patients’ body fluids would be disposed of in a “red-bagged” infectious waste receptacle. (These bags must be labeled to indicate they contain infectious waste.) See Figure 3-53b for an attractive container.

Specimen Toilets

Since each patient must empty her bladder before an examination, an OB-GYN suite needs a minimum of two toilet rooms. If it is possible to locate the toilet rooms near the nurse station or lab (see Figures 5-3 and 5-4), a specimen pass-through in the wall can eliminate the need for the patient to carry the urine specimen to the nurse station. Toilet rooms need a hook for hanging a handbag and coat, a shelf for sanitary napkins and tampons, and a receptacle for sanitary napkin disposal. It would be a nice touch to use a decorative vinyl wallcovering and/or attractive ceramic tile in the bathrooms along with a piece of art.

Laboratory

The laboratory should be at least 10 × 12 feet and must include a sit-down space for a microscope and a countertop space for centrifuge and an autoclave. Space should be allotted for an undercounter refrigerator. If the physicians elect to do a good deal of lab work in the suite, include a blood draw area and adequate countertop space for an automated clinical analyzer. The reader is referred to Chapter 3 for a discussion of CLIA regulations and an explanation of why physicians do little lab work in their suites these days.

Urogynecology

Gynecologists with a subspecialty in urology are called urogynecologists (see Figure 5-4). This is also referred to as women’s pelvic floor medicine. Although in many respects their offices are similar to OB-GYN offices, there are some differences in the types of tests and procedures performed. Women with overactive bladders may receive cystoscopic injections of Botox in the bladder. This requires a sink and countertop for preparing the injection. Other procedures include endoscopic urethral injections for incontinence. Urodynamic studies require a minor procedure room with immediate access to a toilet. These are bladder function studies that require a catheter in the bladder and rectum and a portable flow meter nearby. A specialized, motorized urodynamics chair is used in this room. Another method of treating urge incontinence involves posterior tibial nerve stimulation using an acupuncture needle near the ankle. This 30-minute treatment can be done in a recliner chair, but one may not want to tie up a room devoted to this alone, in which case an exam table can be used. The room designated for this needs to be near the urodynamics procedure room because typically the same nurse does it. Some practices are bringing in a physical therapist to treat pelvic floor disorders. Treatment can be performed in a small room with a physical therapy–type flat table; no sink is required. In this practice an ultrasound machine may be moved from room to room, which means it needs to be stored in a closet with a lockable door. In this specific practice, patients change clothes behind the drape. After the procedure, the physician charts at the desk while the patient dresses, and then they sit together and chat.

An office for surgery scheduling is required in this suite. It should provide a private place for patients to schedule and discuss surgeries.

Perinatology

Obstetricians may have a subspecialty in maternal fetal medicine focusing on the care of the fetus and complicated high-risk pregnancies. Large exam rooms are required as each will have a large ultrasound machine placed at the patient’s right side and a large 55- or 60-inch flat screen monitor mounted on the wall in a location and height where the patient and family can see it, which is typically on the patient’s left side (see Figure 5-9). It is not mounted in front of the patient because it is hard for patients to see over their bellies, especially with multiple fetuses. Images from the ultrasound exam are shown on the monitor and also accessible from the physicians’ reading room, usually viewed on a large screen. If something abnormal is detected, he or she will come into the exam room to discuss it with the patient or the consultation may occur in a private office. Offices for genetic counseling need to be provided. Tests for Down Syndrome and other risk factors are evaluated. Patients and families may experience considerable stress both prior to and after the examination, whether in anticipation of how things are going or perhaps after finding out that something is amiss, the worst of these being the news of a miscarriage. The office design should incorporate a number of positive distractions and stress-reduction features, have a soothing color palette, and comfortable seating. Remember that ultrasound rooms need to have dimmable lights—in this case, that means all exam rooms.

Interior Design

Physicians in this specialty often like a well-designed consultation room, although it is rare for patients to be escorted to this room at the end of an examination because it slows down patient flow. Therefore, this room functions as a private office for a physician. The room may be designed along the lines of a residential library or den, with a wood floor and Oriental rug, bookshelves, fabric wallcovering, elegant upholstery fabrics, and a unique desk. Window treatment, likewise, may be more like one would find in a residence rather than in a medical office.

The waiting room, as well as the rest of the suite, ought to be designed to appeal to women. This may take the form of sunny colors and a garden theme with floral upholstery fabrics, or it may be elegant and sophisticated (see Color Plate 10, Figure 5-11). If a physician’s leanings are traditional, the style could be formal with wood moldings, Chippendale chairs with petit point upholstery, fabric wallcoverings, and Oriental rugs on a wood floor. Or, the physician’s style might be less formal—country French. The options are many. This specialty allows the designer a great amount of freedom; obstetricians and gynecologists usually like to present a well-decorated office to their patients. Whatever the design style, chairs should not be so soft or so low that it is difficult for pregnant women to disengage themselves.

Figure 5-11. Waiting room, ophthalmology office.

In summary, the patients here—due to the nature of the specialty—are generally happy, and this upbeat mood should be enhanced by the interior design. All rooms except exam rooms, laboratory, minor surgery, and toilets may be carpeted.

BREAST CENTERS

Historically, mammography screening has been available to women in diagnostic imaging (radiology) centers and, occasionally, in the offices of large OB-GYN practices. In recent years, however, more comprehensive breast care services have been provided in specialized facilities that offer women more psychosocial support and a full range of services, should they be diagnosed as symptomatic. Even when mammography is part of a diagnostic imaging suite, the goal is usually to separate it from the other imaging modalities, creating a separate entrance and identity (see Figures 6-14 and 6-16).

Depending on the anticipated volume of procedures and the potential as a feeder to oncology services, the breast center may be totally independent of diagnostic imaging, having its own ultrasound, mammography, and stereotactic rooms, as well as reading areas. The proliferation of well-designed, high-profile breast centers in recent years is a reflection of the increased awareness of the benefits of early detection as well as a response to reaching out to women who make most of the healthcare decisions for their families.

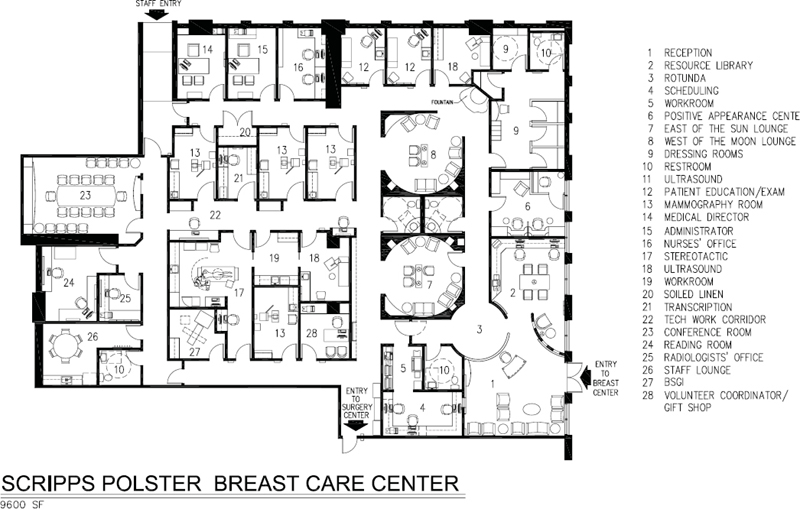

The breast care center in Figure 5-12, Carol Ann Read, is located on the first floor of a hospital with direct access by elevator to a surgery center; the one in Figure 5-13 is also under a hospital’s license but located in a medical office building with direct access to an ambulatory surgical center. The facility in Figure 5-14 is also under a hospital’s license and is located in an MOB. All of these facilities have outstanding design features in addition to being highly functional in terms of space planning and critical adjacencies.

Figure 5-12. Space plan, Carol Ann Read Breast Health Center, 12,000 square feet.

Figure 5-13. Space plan, Scripps Polster Breast Care Center, 9,600 square feet.

Figure 5-14. Space plan of 49 Wells Breast Diagnostic Center, 8,000 square feet, Palo Alto Medical Foundation, a Sutter Health Affiliate.

Psychological Context

The possibility of breast cancer strikes such a chord of fear and terror in many women that the anticipation of having a mammogram fills them with dread. (This, despite the fact that more women die of heart disease every year than breast cancer.) Understanding this context of fear of the unknown, and perhaps the subconscious fear of the possibility of losing a breast if a lesion or tumor is discovered, causes some women to arrive at the facility in an anxious state of mind. Therefore, a design that is calming and soothing will be appreciated. Research shows that connecting people to nature with a view of a garden, or a water element like a large fountain, and natural light has immediate physiological benefits in terms of reducing stress. Even a simulated view of nature as in large-scale photographs and back-lit photo images is effective. Providing options and choice also reduces stress. Patients who visit the Scripps Breast Care Center (Figure 5-15) have a choice of five options to fill their time while waiting for the procedure. After gowning, they may sip tea from a china tea service and read magazines, watch a video on breast self-exam, visit the resource library to select a book or video or go online to research women’s health topics (Figure 5-16), tour the corridors to see the many works of art and contemporary crafts, or visit the positive appearance center to select a gift. Positive diversions, according to research, also reduce stress. These include aquariums, fountains, soothing music, interactive works of art, or anything that distracts one from worry and fear.

Figure 5-15. Waiting room with concierge desk, Scripps Polster Breast Care Center, La Jolla, California.

Figure 5-16. Ethel Rosenthal Resource Library, Scripps Polster Breast Care Center, La Jolla, California.

Psychological Support

One of the advantages of screening at a breast center, as opposed to having a mammogram at a diagnostic imaging facility, is the psychosocial support that is often available to women who prove to be symptomatic. In the typical scenario, a woman who learns she has a suspicious growth has to wait an agonizing week or two to book an appointment with a primary care physician who will likely refer the patient for further diagnostic studies. That interval of time can be torturous, whereas, in a breast center, psychosocial support is immediately available through a patient navigator, counselors, and nurses. Further diagnostic tests can be conducted at the same site with care coordinated by a concerned and familiar team of individuals. A connection to the breast center can be maintained even after surgery and other types of therapy, by virtue of counseling and educational programs as well as support groups.

Scope of Services

Screening and Diagnosis

- Screening and diagnostic mammography

- Mammography with tomosynthesis

- Clinical breast examination

- Ultrasound and ultrasound-guided biopsy

- Stereotactic-guided core biopsy

- Stereotactic-guided Mammotome™ biopsy

- Needle localization biopsy

- Breast Specific Gamma Imaging (BSGI)

- ABUS Automated Breast Ultrasound

Education and Outreach

- Education in breast self-examination and breast health

- Positive appearance center with wigs, scarves, hats, and prostheses

- Resource library with Internet access and guidance

Wellness Programs

- Healthy lifestyle programs

- Nutrition counseling

- Complementary therapy resources

Professional and Support Services

- Peer survivor program (“buddy” matching)

- Support groups

- Genetic risk assessment and counseling

- Patient and family education

- Multidisciplinary pretreatment planning conferences

- Second-opinion consultation services

- Lymphedema/rehab services

Space-Planning Considerations

The space planner may wish to consider these space-planning features:

- Lay out procedure rooms with separate entries for tech and patient: techs enter rooms from a tech work corridor that includes workstations, view box, and access to darkroom (see Figures 5-12 and 5-13).

- Instead of a conventional reception window, consider using a concierge desk, staffed by a volunteer, in the main lobby to greet and check-in patients (see Figure 5-15).

- If possible, provide a connection to a surgery center. This provides the greatest privacy and convenience for women who have had a needle localization and now have to proceed to surgery for biopsy (see Figures 5-12 and 5-13).

- Separate “screening” mammography patients from “symptomatic” in gowned waiting (see Figures 5-12 and 5-13).

- Provide a separate and identifiable entry when part of a larger clinic setting (see Figures 6-14 and 6-16).

- Provide acoustically and visually isolated (from patients) staff area with lounge, conference room, restrooms, film reading, and offices for radiologists and medical director (see Figures 5-12, 5-13, and 5-14).

- Provide a resource library alongside the waiting area (see Figures 5-13 and 5-16).

Interior Design Amenities

- Consider wall sconces and other indirect lighting in procedure rooms as well as exam/patient education rooms.

- Consider a painting for the floor under the stereotactic table (protected by a piece of Lexan®), where patient is lying on stomach, looking down (Figure 5-27).

Figure 5-27. Stereotactic room with table raised as it would be during the procedure.

(Photo: Jain Malkin) - Furnish the lobby or waiting room like a living room with a variety of seating, interesting ceilings, lighting, and artwork (See Color Plate 12, Figure 5-20; and Color Plate 13, Figures 5-21 and 5-22).

Figure 5-20. Intimate seating groupings offer privacy and comfort in settings such as breast health and diagnostic imaging.

(Courtesy of Ewing Cole; Photographer: Bernstein Associates)

Figure 5-21. Waiting area of Carol Ann Read Breast Health Center.

(Design: Jain Malkin Inc.; Ratcliff Architects; Photographer: Copyright © 2008 Douglas A. Salin)

Figure 5-22. Reception desk with light well overhead and custom mobile art, Carol Ann Read Breast Health Center.

(Design: Jain Malkin Inc.; Ratcliff Architects; Photo courtesy of Linda E. Grant, Alta Bates Summit Foundation) - An intimate, serene inner sanctum was created in a challenging below-grade space with low ceilings and no windows, by building banquette seating around the perimeter, complemented by careful detailing, attention to lighting, and a few surprises such as the opening in the ceiling (Figure 5-17).

Figure 5-17. Waiting room, Hoag Hospital Breast Care and Imaging Center.

(Architecture and Interior Design: Taylor & Associates Architects, Newport Beach, California; Photographer: Farshid Assassi) - Provide elegant, private dressing rooms (see Figures 5-14, 5-18, and 6-20a).

Figure 5-18. Subwaiting/changing area of 49 Wells Breast Diagnostic Center, Palo Alto Medical Foundation, a Sutter Health Affiliate.

(Architecture and Interior Design: Hawley Peterson Snyder; Photographs by David Wakely) - A considerable amount of literature is dispensed, which requires racks to keep it sorted and neat.

- Gowned waiting can be designed as a living room with an inset area rug and an opening on one or two sides to provide a view of something interesting. The suite plan in Figure 5-13

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses