Key points

- •

Patient selection and evaluation are key to the management of the aging face.

- •

The surgeon must thoroughly understand which technique is safe for each individual patient.

- •

The surgeon must also determine which technique is safe in their hands.

After reading the authors’ other article, “Surgical Anatomy of the Superficial Musculo-Aponeurotic System,” the reader should have a better understanding of how the variation can appear in the skin subcutaneous superficial musculo-aponeurotic system (SMAS) and muscles layers. Faces in individuals age at different rates. Some individuals resist aging until much later; this can be due to both genetic and environmental factors. It is now understood that different layers of the face run continuously throughout the face. From a surgical standpoint, the face is divided into 3 zones: upper, middle, and lower thirds. The upper third includes the forehead and upper lids; the middle third includes the lower lids mid face and extends over the nasolabial folds and upper lip; and the lower third includes the lower lip chin, jowls, and neck. The exact margin of each zone is not important as long as one has a systematic approach in diagnosing each area and an understanding of which surgical intervention can be used to correct these aging deformities.

It is best to address all zones together to have the most surgically harmonious outcome.

When accessing the aging face, one should have a systematic approach to evaluation.

Nahai once stated that there is not a facelift for all seasons, but all facelifts do have an incision, flap elevation, addressing of vectors fixation, and ancillary procedures in common. Ancillary procedures can be divided into volume management and resurfacing procedures.

This article focuses on the levels of dissection in approaching the management of the SMAS.

For simplicity facelifts are categorized as follows:

- 1.

Short scar: traditional and minimal-access cranial suspension (MACS lift)

- 2.

Traditional facelift: posterior auricular incision and submental incision

Fig. 1 diagrams a short incision that is used in the MACS lift.

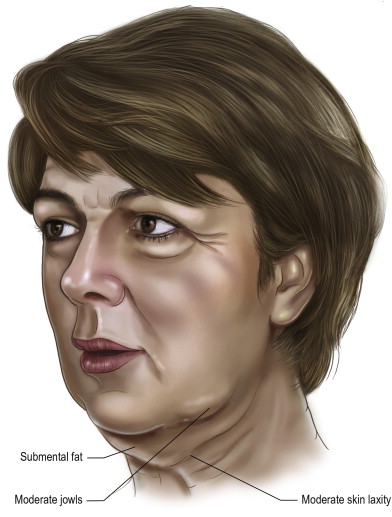

The above-mentioned categories are based on their incisions. Short-scar facelifts and MACS lift are best suited for patients that have minimal aging below the jawline. This concept is an important diagnostic concept to understand for the novice surgeon. In general, these facelift procedures are usually suited to patients in their early 40s to 50s. These patients present with malar descent and jowling. They show absent or minimal platysmal banding and cervical facial banding. Figs. 2–5 outline the different presentations of Bakers classification 1–4.

- •

Early 40–50s

- •

Aging confined to face

- •

Early jowling

- •

Minimal neck laxity

- •

Submental fat may be present

- •

Microgenia

- •

Good cervical skin laxity

- •

May wear hair up

- •

Late 40s to late 50s

- •

Moderate jowling

- •

Moderate neck skin laxity

- •

Submental and submandibular fat

- •

May have microgenia

- •

Age late 50s to early 70s

- •

Significant jowls

- •

Moderate cervical/neck skin laxity

- •

Submental/submandibular fat

- •

Platysmal bands on animation

- •

May have microgenia

- •

Age late sixties to seventies

- •

Significant jowls

- •

Poor cervical skin laxity

- •

Skin folds below cricoid

- •

Submental/subplatysmal fat

- •

Platysmal bands on animation

- •

Deep cervical creases

No active platysmal bands

Traditional facelifts are best performed in patients that have moderate to advance stages of facial laxity. The posterior auricular incision can have variation from surgeon to surgeon and from patient to patient. A submental incision to access the anterior neck is essential for management of the platysma.

Management of the SMAS has numerous variations and modifications are being presented constantly. For simplicity, the management of the SMAS can be categorized as follows:

-

SMAS imbrication

-

Lateral SMAS-ectomy with plication

-

SMAS elevation

Both short-scar facelifts and traditional facelift technique encompass different techniques of SMAS management. The aggressiveness of SMAS management is related primarily to the individual surgeon comfort and secondarily to patient evaluation and anatomic presentation. As surgeons evolve to be more comfortable in their management modifications, more aggressive procedures are manipulated.

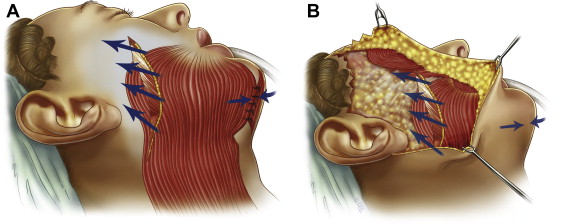

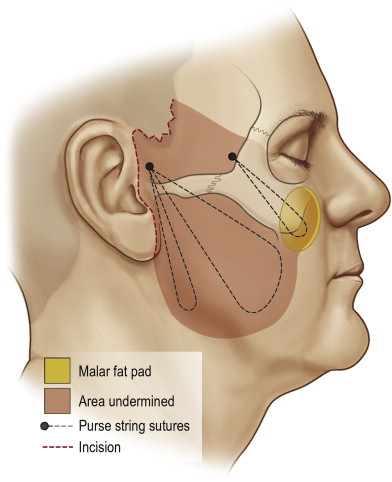

All the above SMAS management procedures are based on the understanding of replacing the SMAS to its once, more youthful appearance. As one ages, the SMAS descends because of a combination of loosening of the ligamentous attachment and a decrease in volume in the subcutaneous portion. Understanding the vectors of the aging face is important in the management of the SMAS. All the procedures rely on the correct vector placement in the final placement of the SMAS as diagrammed in Fig. 6 .