Management of condylar fractures remains a source of ongoing controversy. While it appears that many condylar fractures can be managed nonsurgically, recognition of cases that require surgical intervention and selection of an appropriate procedure are paramount to success in treating these injuries. There are a variety of special considerations that are peculiar to the condylar region. This article discusses anatomic considerations, classification of condylar fractures, indications for surgery, treatment options, and complications. The goals of treatment include restoration of function and esthetics. Careful consideration and attention to the principles of fracture management, and the role of the condyle as an articulating unit and growth center, must be taken into account for the successful management of these injuries.

Condylar fractures are a unique subset of traumatic injuries to the maxillofacial skeleton. While these injuries must be managed according to the general principles of fractures management, there are a variety of special considerations that are peculiar to the condylar region that are not present in fractures of the nonarticulating maxillofacial skeleton. These additional points of consideration are due to the function of the condyle as a moving unit within the temporomandibular joint and the fact that the condylar unit serves as a mandibular growth center. As a result of the functional requirements of the condylar area, the oral and maxillofacial surgeon must balance the principles of maxillofacial fracture management with restoration of temporomandibular joint function and the potential impact of the injury on growth and development. The salient features of condylar fracture management are addressed along with illustrative cases to demonstrate certain key points.

Anatomic considerations

In order to appreciate the complexity of the temporomandibular joint it is important to understand the anatomy of this articulation and how the anatomy is altered by traumatic injuries. The condyle resides in the articular fossa and is surrounded circumferentially by the capsular ligament which is a tendinous expansion arising from the periosteum of the margins of the glenoid fossa and inserting on the most superior aspect of the condylar neck. This tightly bound capsular ligament helps to maintain the condyle within the fossa except under the most severe of forces. The function of the capsular ligament is supported to some degree by the collateral ligaments and the lateral or temporomandibular ligaments. The collateral ligaments arise off of the medial and lateral disc margins and blend with the capsular ligament onto the condylar neck. The lateral ligaments are present only on the lateral aspect of the joint space and condyle and also serve to restrict extreme movements. Of note, these ligaments all serve to prevent dislocation of the condyle from the articular fossa and also to maintain the disc–condyle–fossa relationships. When these anatomic relationships are disturbed, the effects on the condyle can become problematic.

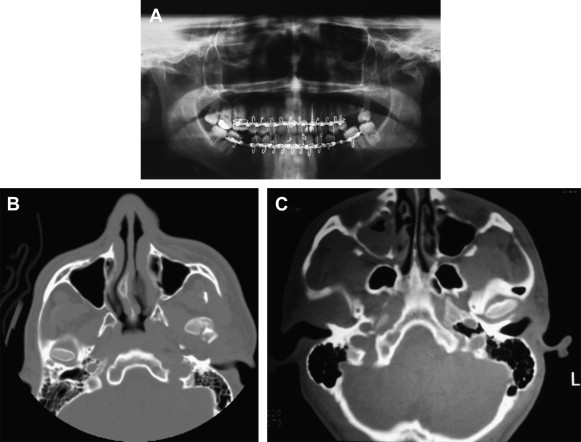

Muscular attachments to the condylar region are limited and include mainly the lateral pterygoid muscle. The lateral pterygoid arises from the lateral aspect of the lateral pterygoid plate and from the infratemporal surface of the greater wing of the sphenoid. The lateral pterygoid is composed of two distinct muscle bellies. The inferior belly inserts onto the medial aspect of the condylar neck at the pterygoid fovea. The superior head inserts onto the disc, capsule, and medial surface of the condyle. Owing to this unopposed muscle pull, fractures of the condylar head often exhibit displacement anteriorly in the glenoid fossa as the lateral pterygoid exerts its influence ( Fig. 1 A–C). For the same reasons, subcondylar fractures often exhibit anterosuperior rotation. Low subcondylar fractures may have variable muscle pull from the medial pterygoid muscle and the masseter depending upon fracture configuration.

The articular fossa is bounded by a number of vital structures. Superiorly, the glenoid fossa is bounded by the contents of the middle cranial fossa. Rarely, fractures involving the articular fossa occur through the roof of the glenoid fossa resulting in intracranial injury. Posteriorly, the articular fossa is bounded by the external auditory canal. Injuries with a significant posterior vector may cause injuries to the middle ear, disruption of the external auditory canal, and, occasionally, stenosis or narrowing of the canal.

The role of the disc or meniscus in internal derangement can be debated; however, it may play a pivotal role in preventing complications associated with these fractures. While the disc is positioned between the condyle and the articular fossa in the normal temporomandibular joint it serves as an anatomic barrier to separate the condylar head from the glenoid fossa. Although it is not clear whether abnormalities in disc position will have any impact on fractures involving the joint space, it has been suggested that the presence of the meniscus plays an integral role in preventing ankylosis of the temporomandibular joint after condylar fractures. It seems that the development of posttraumatic ankylosis is a multifactorial process whereby a number of conditions must be in place to result in this serious complication.

Anatomically, the adult condyle is composed of dense cortical bone and a variable amount of cancellous bone depending upon the age of the patient. The condylar neck is generally long and slender. This configuration results in a preponderance of subcondylar fractures in adults rather than fractures of the condylar head. This must be held in contrast to the morphology and make-up of this area in children. In the pediatric population, cortical bone is generally thinner and more elastic than in the adult population. The condyle, serving as a growth center, is composed of abundant marrow spaces. In addition, the condylar neck in the pediatric mandible is shorter and broader than in that of the adult. As a consequence, condylar process fractures are more common in children than they are in adults.

Classification of condylar fractures

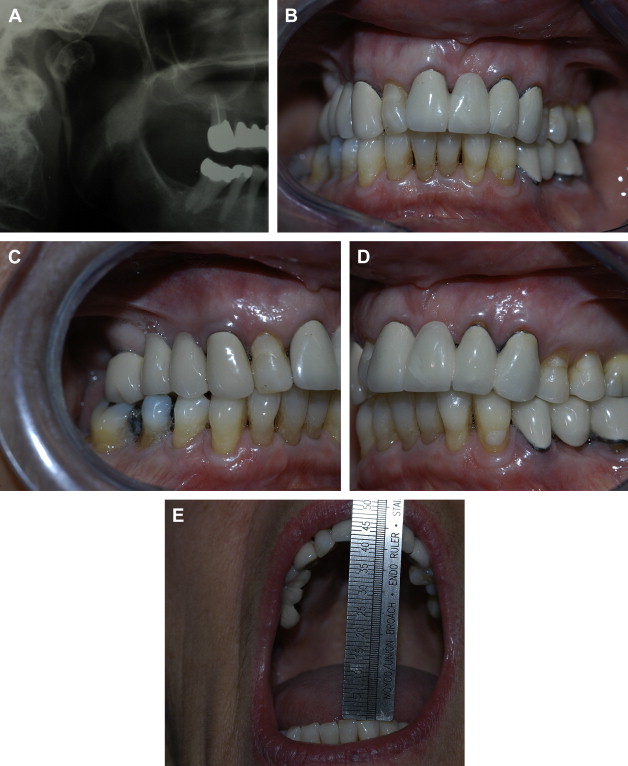

There have been many attempts to create classification systems for fractures of the mandible. Fractures of the condylar region may be classified into intra-articular and extra-articular categories. This classification is somewhat simple but serves a useful purpose in treatment algorithms. Operative management will often depend upon whether the fracture is intra-articular or extra-articular in nature. Intra-articular fractures can be further subdivided into lateral pole fractures, medial pole fractures, condylar head fractures contained within the capsular ligament ( Fig. 2 A), and comminuted fractures. Since surgical treatment options are generally limited in cases of intra-articular fracture, these injuries may often be treated nonoperatively. The ability to reduce and fixate these fractures is hampered by limited access and small fragment size which can make fixation of these fractures difficult. Nonoperative techniques based upon physiotherapy and the recovery of range of motion and masticatory function are the most commonly employed modalities in these types of fractures. Avoidance of posttraumatic ankylosis is an important consideration; and physiotherapy and range of motion exercises are the most effective techniques in preventing this complication. Lateral pole fractures are fairly common and generally require nothing more than palliative treatment such as analgesics and soft diet. The lateral pole fracture typically does not affect articulation or condyloramal length which is maintained by the intact portion of the head of the condyle which remains attached to the condylar neck and ramal components of the mandible. Likewise, medial pole fractures typically do not cause disturbances in occlusion or condyloramal length. The treatment of these types of fractures remains largely symptom based.

Comminuted fractures of the condylar head remain the most problematic of the intra-articular fractures. This is due to the inability to reduce and fixate these fractures. Of all the fractures of the condylar region, the comminuted fracture type has the potential to lead to the most significant complications of all these injuries. Once multiple bone fragments are dispersed throughout the articular fossa, the potential exists for union of the scattered fragments in ectopic positions. Heterotopic bone formation may also ensue compounding the problem. In the case of the pediatric patient, with thin layers of cortical bone surrounding large marrow spaces, these types of fractures disperse an abundant supply of potent osteogenic material throughout the fossa. When this occurs in concert with guarding and immobilization, it is not difficult to understand how ankylosis can occur. The role of the meniscus in the prevention of ankylosis requires mention. If the capsular ligament is not disrupted, all of the fragments should lie within the fossa. Furthermore, the meniscus should serve to separate the condyle and its bony fragments from the articular fossa. This would likely be enough to prevent ankylosis as it would separate the condylar stump and all of the fragments from fusing to the glenoid fossa. Abnormalities in condylar morphology would still exist as the bone fragments consolidated in their aberrant position.

The management of extra-articular fractures of the condylar region is subject to a much greater debate. A variety of treatment algorithms have been proposed based upon degree of displacement, position of the displaced condylar fragment, loss of condyloramal length and angulation of the proximal fragment to the ramus. Treatment options for these injuries include observation with soft diet, functional therapy with guiding elastic traction, closed reduction and open reduction with or without internal fixation. Treatment decisions are based upon the likelihood of postoperative complications and whether the complications are more likely with or without surgical treatment. These concerns form the basis of the controversy in the treatment of these injuries.

Classification of condylar fractures

There have been many attempts to create classification systems for fractures of the mandible. Fractures of the condylar region may be classified into intra-articular and extra-articular categories. This classification is somewhat simple but serves a useful purpose in treatment algorithms. Operative management will often depend upon whether the fracture is intra-articular or extra-articular in nature. Intra-articular fractures can be further subdivided into lateral pole fractures, medial pole fractures, condylar head fractures contained within the capsular ligament ( Fig. 2 A), and comminuted fractures. Since surgical treatment options are generally limited in cases of intra-articular fracture, these injuries may often be treated nonoperatively. The ability to reduce and fixate these fractures is hampered by limited access and small fragment size which can make fixation of these fractures difficult. Nonoperative techniques based upon physiotherapy and the recovery of range of motion and masticatory function are the most commonly employed modalities in these types of fractures. Avoidance of posttraumatic ankylosis is an important consideration; and physiotherapy and range of motion exercises are the most effective techniques in preventing this complication. Lateral pole fractures are fairly common and generally require nothing more than palliative treatment such as analgesics and soft diet. The lateral pole fracture typically does not affect articulation or condyloramal length which is maintained by the intact portion of the head of the condyle which remains attached to the condylar neck and ramal components of the mandible. Likewise, medial pole fractures typically do not cause disturbances in occlusion or condyloramal length. The treatment of these types of fractures remains largely symptom based.

Comminuted fractures of the condylar head remain the most problematic of the intra-articular fractures. This is due to the inability to reduce and fixate these fractures. Of all the fractures of the condylar region, the comminuted fracture type has the potential to lead to the most significant complications of all these injuries. Once multiple bone fragments are dispersed throughout the articular fossa, the potential exists for union of the scattered fragments in ectopic positions. Heterotopic bone formation may also ensue compounding the problem. In the case of the pediatric patient, with thin layers of cortical bone surrounding large marrow spaces, these types of fractures disperse an abundant supply of potent osteogenic material throughout the fossa. When this occurs in concert with guarding and immobilization, it is not difficult to understand how ankylosis can occur. The role of the meniscus in the prevention of ankylosis requires mention. If the capsular ligament is not disrupted, all of the fragments should lie within the fossa. Furthermore, the meniscus should serve to separate the condyle and its bony fragments from the articular fossa. This would likely be enough to prevent ankylosis as it would separate the condylar stump and all of the fragments from fusing to the glenoid fossa. Abnormalities in condylar morphology would still exist as the bone fragments consolidated in their aberrant position.

The management of extra-articular fractures of the condylar region is subject to a much greater debate. A variety of treatment algorithms have been proposed based upon degree of displacement, position of the displaced condylar fragment, loss of condyloramal length and angulation of the proximal fragment to the ramus. Treatment options for these injuries include observation with soft diet, functional therapy with guiding elastic traction, closed reduction and open reduction with or without internal fixation. Treatment decisions are based upon the likelihood of postoperative complications and whether the complications are more likely with or without surgical treatment. These concerns form the basis of the controversy in the treatment of these injuries.

Indications for surgical management of condylar fractures

There are well-accepted absolute indications for open treatment of subcondylar fractures. These absolute indications are as follows:

-

Dislocation of the condyle into the middle cranial fossa

-

Inability to open mouth or establish occlusion after conservative therapy

-

Intra-articular foreign body

-

Lateral extracapsular displacement.

There are also a variety of relative indications:

-

Medical necessity (alcoholism, seizure disorder, bulimia, and so forth)

-

Displacement of the condyle out of the fossa

-

Bilateral mandibular fractures involving subcondylar fracture.

In addition, there are proposed absolute indications for conservative therapy which include the following

-

Intracapsular fractures

-

Fractures in small children

-

Fractures without dislocation.

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses